Translate this page into:

Efficacy of moisturizers in paediatric atopic dermatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials

Corresponding author: Associate Prof. Arucha Treesirichod, Department of Paediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, Srinakharinwirot University, Ongkharak, Nakhonnayok, Thailand. trees_ar@yahoo.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Kritsanaviparkporn C, Sangaphunchai P, Treesirichod A. Efficacy of moisturizers in paediatric atopic dermatitis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2022;88:22-31.

Abstract

Background:

Topical moisturizer is recommended for atopic dermatitis.

Aims:

The aim of the study was to investigate the knowledge gap regarding the efficacy of moisturizer in young patients.

Methods:

A systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted on randomised controlled trials comparing participant’s ≤15 years with atopic dermatitis, receiving either topical moisturizer or no moisturizer treatment. Certainty of evidence was assessed using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework.

Results:

Six trials were included (intervention n= 436; control n= 312). Moisturizer use extended time to flare by 13.52 days (95% confidence interval 0.05–26.99, I2 88%). Greater reduction in risk of relapse was observed during the first month of latency (pooled risk ratio 0.47, 95% confidence interval 0.31–0.72, I2 28%) compared to the second and third months (pooled risk ratio 0.65, 95% confidence interval 0.47–0.91, I2 35% and pooled risk ratio 0.63, 95% confidence interval 0.47–0.83, I2 33%, respectively).Treated patients were 2.68 times more likely to experience a three–six months remission (95% confidence interval1.18–6.09, I2 56%). Moisturizer minimally improved disease severity and quality of life.

Limitations:

There is a dire need to conduct randomised controlled trials with more robust and standardised designs.

Conclusion:

Moisturizer benefits young patients with atopic dermatitis. However, more research is needed to better estimate its efficacy.

Keywords

Emollient

moisturizer

children

atopic dermatitis

Plain Language Summary

Atopic dermatitis is an inflammatory skin disease with skin dryness, itching and recurring flares that impacts patient’s quality of life. Moisturizer is a widely recommended treatment and while its benefit has been explored in adult, we are uncertain how well they work in children less than 15 years. To meet this end, we searched the literature for trials comparing results in children given moisturizer versus ones without treatment to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis. Through combining data from six studies, we found that regular users have a longer flare-free period (by two weeks) and are 2.7 times more likely to remain flare-free for three–six months compared to non-users. Moisturizer relieves personal symptoms, namely, itching and sleep loss, but not physician-assessed signs, such as skin dryness, redness, swelling and crusting. Its use marginally boosts quality of life. However, the shortcoming of our research is that there is lack of well-designed trials included for analysis, thus diminishing the certainty of evidence. Nevertheless, moisturizers appear to be beneficial for treating atopic dermatitis in children.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis is a chronic relapsing inflammatory condition.1-4 Its hallmark manifestations are baseline xerosis with acute remitting flares of pruritic eczema followed by periods of temporary remission.1,3 With over 90% of cases occurring within five years of age, atopic dermatitis notably affects the well-being of young patients and caregivers. Poor sleep, lowered self-esteem and missed school days are common indicators of its impact on patients’ lives.1,3,5 Therefore, preventing flare-ups and alleviation of disease severity while in remission is crucial to ensure good quality of life.1,6

During disease maintenance, recommendations advocate three practices: daily moisturizer application after warm bath/shower with non-soap cleansers, antiseptic control with diluted bleach bath at least twice weekly and avoidance of known allergens, irritants, or extreme temperatures.7-10 Monotherapy moisturizer may be sufficient for primary treatment of acute exacerbations in mild disease.9,10 For moderate to severe cases, topical corticosteroid and topical calcineurin inhibitor may be added in a stepwise manner to the baseline moisturizer regimen, along with adjunctive use of wet wrap therapy.9,10 Therefore, moisturizer plays an integral role in both maintenance and preventing of exacerbation, regardless of severity.11

Moisturizers are a collective group of products that hydrates the skin, which ultimately relieves pruritus and xerosis.12,13 Their active ingredients include humectants that aid water retention in stratum corneum, occlusives that prevent water loss and emollients that smoothen the skins surface.14 Different formulations, such as soap substitutes and bath moisturizers, are available for convenient usage in multiple contexts, which this review will focus on. The topical formulations are among the cornerstones for atopic dermatitis management.9

Pooled data from all ages have shown that daily application of moisturizers alleviated disease severity, prolonged clinical latency and improved quality of life.11 However, in clinical practice children are often less tolerant to this time-consuming therapy compared to adults, possibly due to irritation of the skin, an unpleasant smell, or a greasy sensation.11 The rationale of this study emerged from these limitations in compliance, in which results from adult may not completely translate to children. Since paediatric care poses unique challenges, we identified the need to investigate efficacy of moisturizers in prolongation of clinical latency, alleviation of disease severity and improvement in quality of life, compared to no treatment in atopic dermatitis of children under 15 years through pooling of randomised controlled trial results.

Methods

The systematic review and meta-analysis were conducted and reported in accordance to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guideline.15 The protocol was registered in PROSPERO (CRD42020188379).

Search strategy

We searched Ovid Embase, Ovid Medline, Web of Science, Cochrane Database of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), CINAHL, GREAT and DARE for relevant randomised controlled trials from inception to July 31, 2020. A cross-reference check was attempted to identify additional studies.

Eligibility criteria

Selected studies had to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) participants age ≤15 years old with atopic dermatitis, diagnosed by a physician using U.K. Working Party’s diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis or Hanifin and Rajka criteria, who have received prior treatment and are flare-free at study initiation;16,17 (2) intervention of any type of topical moisturizer, applied daily at any amount or duration and (3) a control group of no moisturizer treatment. Cointervention such as cleansing gel, bodywash, topical corticosteroid, topical calcineurin inhibitor, antibiotics or antihistamine were allowed if both groups were administered the same agent; (4) studies that investigated our pre-specified outcomes and (5) experimental studies that were either a randomised controlled trial or controlled clinical trial published in English.

The required exclusion criteria: (1) Any other forms of moisturizer apart from cream or lotion; (2) studies that compared moisturizer with active ingredient versus standard moisturizer without such ingredient and (3) studies that investigated adjunctive effect of moisturizer with another agent (such as topical corticosteroid, topical calcineurin inhibitor, antibiotics and antihistamines) compared to moisturizer alone.

Data collection

The titles and abstracts were independently reviewed by two authors against the criteria. Full texts were evaluated, when necessary, especially when abstracts did not clarify the participants’ age or presence of a no moisturizer control. Two researchers collected data independently using a data extraction form. Details of participants (age and gender, inclusion and exclusion criteria, baseline data, number randomised and number of dropouts), method (study design, blinding, randomisation, study duration, investigators and outcome assessors), intervention groups (details of treatment regimen, dosage, frequency, location of application and duration), results (types of outcomes collected and timing of assessment), funding source and declarations of interest were collected. Contact with the research authors was attempted when essential information was unclear. Bias was evaluated independently by two authors using the Cochrane ‘Risk of bias’ tool, in which the risk in each bias domain was graded as either ‘high,’ ‘unclear,’ or ‘low.’18 We also intended to assess publication bias using funnel plot analysis, given the known limitations of the method. Any disagreements between the authors were adjudicated by a third reviewer.

Synthesis of results

Our primary outcomes were extension of time to flare in days after the disease has been controlled with moisturizer therapy. The secondary outcomes were risk of relapse after each month of latency and rate of remission (defined as flare-free period of greater or equal to three months), alleviation of global disease severity, individual signs and symptoms and improvement in quality of life. Two authors analysed the data using the random-effects model in RevMan 5.3.18 To analyse dichotomous data, the risk ratio and the corresponding 95% confidence interval were pooled. For continuous data, the mean difference and its standard deviation were used when studies employed the same measurement to quantify an outcome, while standardised mean difference and standard deviation were pooled if different measurements were applied. Time-to-events was calculated as a hazard ratio, which the log hazard ratio and its standard error were utilised to perform meta-analysis through the generic inverse variance method. When studies had a ‘flare rescue’ treatment after the initial maintenance duration, only data pertaining to the maintenance phase were included for our outcome measures. If any data was found to be missing, we would attempt to contact the research authors for relevant details. When necessary, we approximated means or time-to-events from figures reported in the articles.

Finally, the certainty of evidence was assessed by two researchers using the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation framework.19 Starting from a ‘high’ quality level, each comparison was downgraded one level for serious (or two levels if very serious) risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, or imprecision.

Results

Study selection

The initial search retrieved a total of 3590 publications [Figure 1]. After de-duplication, we assessed the titles and abstracts of 1988 studies.We then screened the full text of 94 articles and found six that satisfied the inclusion criteria. Common reasons for exclusion of articles were the use of vehicle/placebo instead of a no treatment control,20-24 and wrong comparisons of topical corticosteroids versus moisturizers.25-28

- Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis flow diagram showing the methodology in selecting articles for final analyses

Study characteristics

Table 1 illustrates the characteristics of included publications.29-34 They were published between 2006 and 2017, were mostly multi-center and conducted in Europe.

| Author and year | Study design | Study duration (months) | Number (intervention, control) | Baseline characteristics | Treatment Arms | Conflict of interest | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean years) | Gender, M (%) | Intervention | Placebo/ vehicle | Cointervention in both groups | ||||||

| Description | Regimen | |||||||||

| Giordano- Labadie et al., 2006. France |

Multicentre, open label, | 2 | 37, 39 | 3.92 | NR | Exomega milk® | Twice daily over whole body | None | Cleansing bar (A-Derma®) | None declared |

| Grimalt et al., 2007. France |

Multicentre, open label, | 1.5 | 91, 82 | 5.96 | 50.3 | Exomega milk® | Twice daily over whole body | None | Hygiene product (not specified) | Pierre Fabre |

| Weber et al., 2015. Germany |

Single centre, open label, | 6 | 21,24 | 3.55 | 53.3 | Eucerin® Eczema Relief Body Crème | Once daily over whole body | None | Hypoallergenic Cleanser (by Beiersdorf Inc. Wilton, CT) | None declared |

| Bianchi et al., 2016. Italy |

Multicentre, open label, | 1 | 28, 27 | 2.5 | NR | Avène Xeracalm balm | Twice daily over whole body | None | Hygeine product (Trixera) | Pierre Fabre |

| Ma et al., 2017. China |

Single centre, single blinded, | 3 | 32, 32 | 5.4 | 42.1 | Cetaphil® Restoraderm ® moisturizer |

Twice daily over whole body | None | Cetaphil® Restoraderm® body wash | Galderma R&D |

| Tiplica et al., 2017. Romania |

Multicentre, Open label, Three arms | 3 | Arm 1:111, Arm 2: 116, Control:108 |

4.10 | 48.1 | Arm 1: Dexeryl® Arm 2: Atopiclair® | Arm 1: Twice daily over whole body Arm 2: Three times daily on affected or previous affected skin |

None | None | Pierre Fabre |

Patients had mild to moderate severity (Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) of 5 to 35 or Investigator Global Assessment of 2 to 3), except for Grimalt et al. were done on moderate to severe disease (SCORAD 20–70).31 The number of participants ranged from 45 to 335 in each study, with a total of 748 subjects (intervention 436, control 312). Participants’ age varied from one month to 12 years. The study durations ranged from one to six months, with a mean length of 2.4 months.

Tiplica et al. had a three-arm design in which the moisturizer of interest, Dexeryl® (Pierre Fabre) and reference emollient, Atopiclair® (Sinclair Pharma) were compared against no treatment.33 Other moisturizers were investigated included Exomega Milk® (Pierre Fabre).30,31 Avène Xeracalm Balm®(Pierre Fabre),29 Eucerin® Eczema Relief Body Crème (Beiersdorf)34 and Cetaphil Restoraderm® (Galderma).32 While Tiplica et al. did not administer any cointervention, the other five studies gave a standardised cleanser or hygiene product to research arms.

Four separate publications have declared their source of funding as the pharmaceutical industry of the studied product.29,31-33 Giordano-Labadie et al. and Weber et al. did not report their sponsorship, but the intervention was manufactured by the company that employed their researchers, making these parties the likely funding sources.30,34

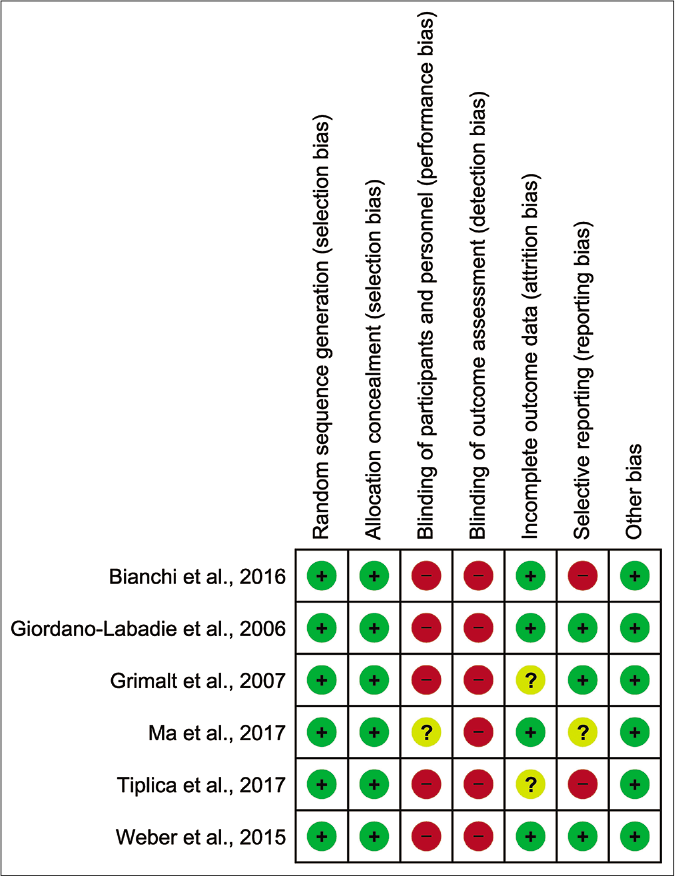

Risk of bias within studies

As summarised in Figure 2, all trials incorporated randomisation and allocation concealment, which limited selection bias. However and most strikingly, investigators and outcome assessments were not blinded in all of the studies.29-34 Two of six publications had an unclear risk for attrition bias due to high dropout rates in the control or had missing data from questionnaires.31,33 Bianchi et al.29 and Tiplica et al.33 demonstrate high risk for publication bias because they did not report results on individual signs and symptoms, although the data were collected as part of their Scoring atopic dermatitis assessments. Taken together, we appraised all included studies as showing a high overall risk for bias. We did not evaluate funnel plot symmetry to assess publication bias due to insufficient number of trials.

- Risk of bias summary: review authors’ judgments about each risk of bias item for each included study

Effect of moisturizer on outcomes

Extension of time to flare

Moisturizer treated participants experienced an extension of 13.52 days in time to flare compared to control [Figure 3a; 3 studies, n=231;95% confidence interval 0.05–26.99, I2 88%].32-34 Apart from the wide confidence interval and limited sample size, the quality of evidence was downgraded to ‘very low’ due to risk of bias, indirectness and inconsistency [Table 2].33,34

- Forest plot for differences in time to flare (days) in moisturizer user versus non-user

| Outcome | Number of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) |

Relative effect (95% CI) | Anticipated absolute effects | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk with No Moisturizer | Risk difference with Moisturizer | ||||

| Extension of time to flare (days) | 231(3 randomized controlled trials) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOWa,b,c,d | - | The mean extension was 0 days | MD 13.52 higher(0.05 higher to 26.99 higher) |

| Risk of relapse after one month of latency | 441(3 randomized controlled trials) | ⨁⨁◯◯ LOWa,c | RR 0.47(0.31–0.72) | 454 per 1,000 | 241 fewer per 1,000(313 fewer to 127 fewer) |

| Risk of relapse after two months of latency | 441(3 randomized controlled trials) | ⨁⨁◯◯ LOWa,c | RR 0.65(0.47–0.91) | 589 per 1,000 | 206 fewer per 1,000(312 fewer to 53 fewer) |

| Risk of relapse after three months of latency | 441(3 randomized controlled trials) | ⨁⨁◯◯ LOWa,c | RR 0.63(0.47–0.83) | 675 per 1,000 | 250 fewer per 1,000(358 fewer to 115 fewer) |

| Rate of remission | 377(2 randomized controlled trials) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOWa,b,c,d,e | HR 2.68(1.18–6.09) | 672 per 1,000 | 278 more per 1,000(60 more to 327 more) |

| Reduction in SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (Scoring atopic dermatitis) score | 613(4 randomized controlled trials) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOWa,b,d,f | - | The mean reduction in Scoring atopic dermatitis was 0 | MD 3.46 lower(6.05 lower to 0.87 lower) |

| Reduction in xerosis | 235(3 randomized controlled trials) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOWa,e,g | RR 0.72(0.50–1.04) | 509 per 1,000 | 143 fewer per 1,000(254 fewer to 20 more) |

| Reduction in redness, swelling, oozing/crusting, scratch marks and lichenification | 224(2 randomized controlled trials) | ⨁⨁◯◯ LOWa,e | - | Not pooled | Not pooled |

| Reduction in pruritus score | 389(2 randomized controlled trials) | ⨁⨁◯◯ LOWa,h | - | Not pooled | Not pooled |

| Reduction in sleep loss score | 483(2 randomized controlled trials) | ⨁⨁◯◯ LOWa,i | - | Not pooled | Not pooled |

| Improvement in quality of life | 559(3 randomized controlled trials) | ⨁◯◯◯ VERY LOWa,k,l | - | Not pooled | Not pooled |

| *The risk in the intervention group (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval, MD: Mean difference, RR: Risk ratio, HR: Hazard ratio | |||||

| Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: We are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect Moderate certainty: We are moderately confident in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different Low certainty: Our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: The true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect Very low certainty: We have very little confidence in the effect estimate: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect |

|||||

|

Explanations a: Downgraded one level for performance, detection and publication bias b: Downgraded one level for inconsistency (serious heterogeneity: I2> 50%) c: Downgraded one level for indirectness (Tiplica et al. allowed the use of topical corticosteroid during remission)32 d: Downgraded one level for imprecision (wide confidence interval) e: Downgraded one level for imprecision (limited sample size) f: Downgraded one level for indirectness (Giordano-Labadie et al., Grimalt et al., and Tiplica et al., allowed the use of topical corticosteroid during remission)29-30, 32 g: Downgraded one level for indirectness (the proportion of patients with xerosis were compared instead of xerosis scores) h: Downgraded one level for indirectness (Bianchi et al. reported changes from baseline score, while Tiplica et al. reported post-study scores between groups)31,32 i: Downgraded one level for indirectness (Tiplica et al. reported post-treatment scores for patients, while Grimalt et al. reported scores for caregivers)29,32 j: Downgraded two levels for inconsistency (Giordano-Labadie et al. and Tiplica et al. reflected improvement in quality of life, while Grimalt et al. did not) 29-30, 32 k: Downgraded one level for indirectness (each included studies utilized different scoring system to assess quality of life) |

|||||

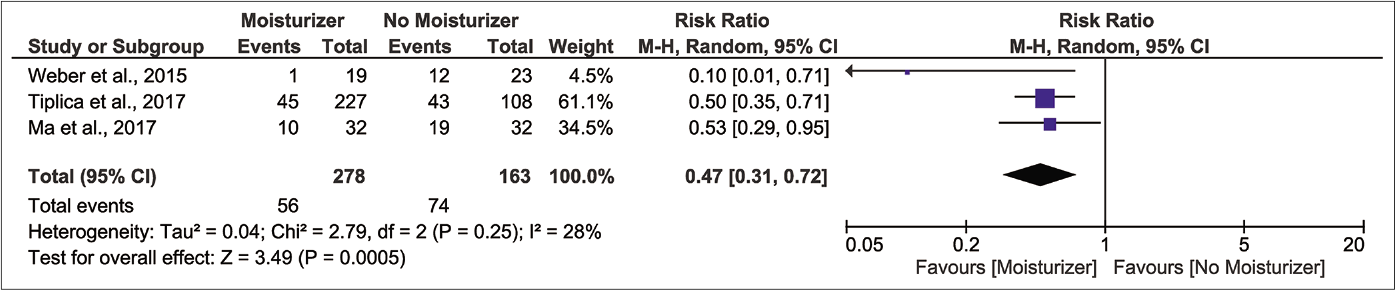

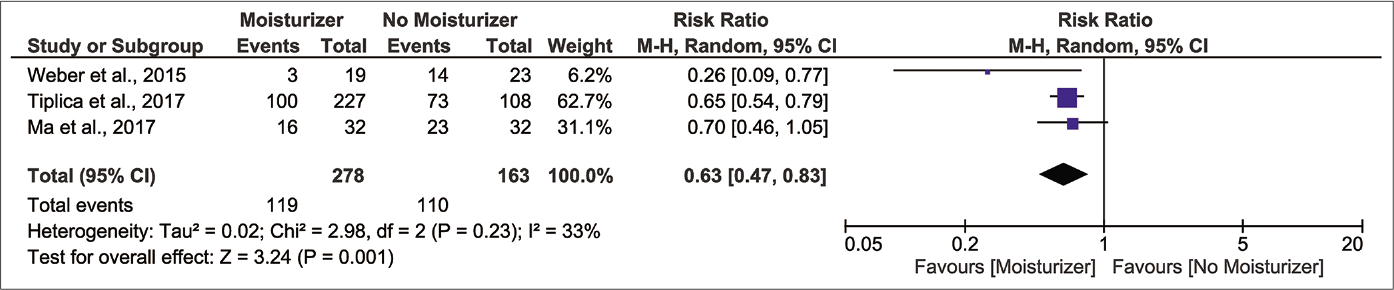

Risk of relapse after each month of latency

Results from three randomised controlled trials (n=441) show that those who applied moisturizer experienced a lower risk of flare-up compared to control after the first month of latency [Figure 3b, pooled risk ratio 0.47, 95% confidence interval 0.31–0.72, I2 28%].32-34 The protective effect was present throughout the second and third month but with smaller magnitudes of effect [Figure 3c, pooled risk ratio 0.65, 95% confidence interval 0.47–0.91, I2 35%; Figure 3d, pooled risk ratio 0.63, 95% confidence interval 0.47–0.83, I2 33%, respectively]. We regarded the certainty of evidence for these outcomes as ‘low’ because of lack of investigator, participant and outcome assessment blinding and indirectness of comparison [Table 2].

- Forest plot for risk of relapse at one month of latency in moisturizer user versus non-user

- Forest plot for risk of relapse at two month of latency in moisturizer user versus non-user

- Forest plot for risk of relapse at three month of latency in moisturizer user versus non-user

Rate of remission

Pooled result from Tiplica et al. and Weber et al., with durations of three and six months, accordingly, demonstrated that moisturizer-treated patients were 2.68 times more likely to experience a remission [Figure 3e; n=378;95% confidence interval 1.18–6.09, I2 56%].Although our finding demonstrates a marked difference, Weber et al. has individually shown a rate of flare that is more than double of Tiplica et al. (Weber et al. 45 participants, hazard ratio 4.95, 95% confidence interval 1.62–15.1; Tiplica et al. 335 participants, hazard ratio 2.01 and 95% confidence interval 1.44–2.81, respectively).33,34 Along with serious heterogeneity, risk of bias, indirectness and imprecision, the certainty of evidence was ranked as ‘very low’[Table 2].

- Forest plot for rate of remission in moisturizer user versus non-user

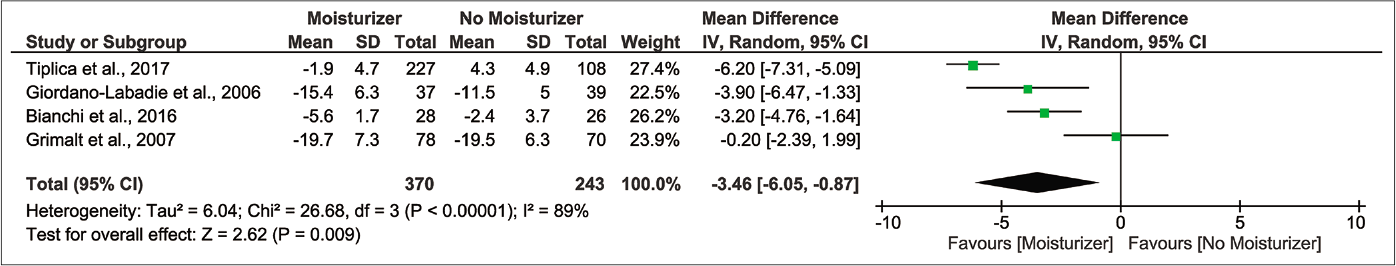

Changes in global disease severity and individual signs and symptoms

When considering global changes in severity, the moisturizer group shows greater improvement in disease status, evidently from a –3.46 points difference in SCORAD from the control [Figure 3f; 4 randomised controlled trials, n=638; 95% confidence interval:6.05––0.87, I2 89%].29-31,33 The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) certainty was ‘very low’ quality due to glaring risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness and imprecision [Table 2].

- Forest plot for differences in SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) index in moisturizer user versus non-user

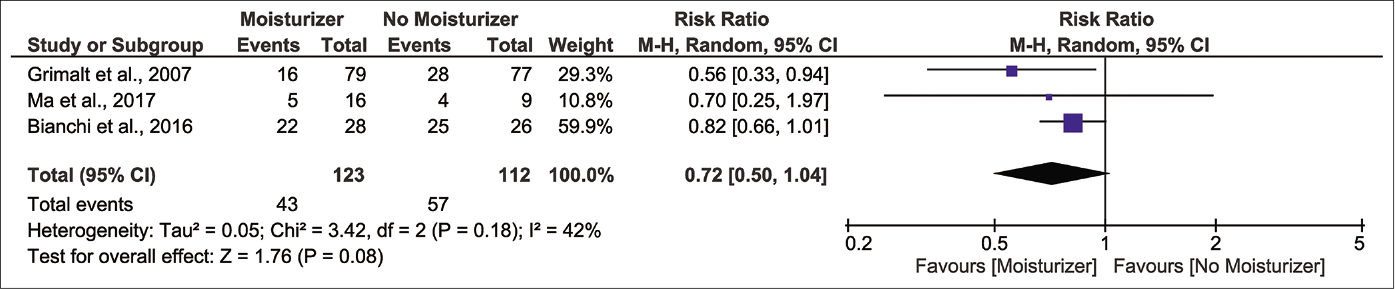

Investigator-assessed signs showed no improvements. Pooled analysis reveals a non-significant reduction in risk of xerosis after product use [Figure 3g;3 randomised controlled trials, n=235; pooled risk ratio 0.72 and 95% confidence interval 0.50–1.04, I2 42%].29,31,32 Grimalt et al. and Giordano-Labadie et al. have described negligible improvements in redness, swelling, oozing/crusting, scratch marks and lichenification, although numerical data were not reported.29-31,33 These outcomes showed ‘very low’ and ‘low’ certainty of evidence, respectively [Table 2].

- Forest plot for risk of xerosis in moisturizer user versus non-user

Moisturizer appeared to alleviate participant-assessed symptoms of pruritus and sleep loss. In Bianchi et al., the moisturizer group demonstrated greater pruritus score changes than the control (–74.6% and –35.9%, respectively), while in Tiplica et al., treatment resulted in lower post-study scores (Dexeryl® 0.42 ± 0.08, P<0.001; Atopiclair® 0.56 ± 0.08, P<0.001; no moisturizer 1.09 ± 0.08). Similarly, for sleep loss, the post-treatment scores were lower in patients and caregivers in Tiplica et al. and Grimalt et al., respectively (Tiplica et al.: Dexeryl® 0.27 ± 0.06, P=0.013; Atopiclair® 0.27 ± 0.06, P=0.014; no moisturizer 0.47 ± 0.06; Grimalt et al. 0.26 ± 0.48 vs. 0.53 ± 0.77, P=0.006).31,33 The GRADE certainty for both outcomes were ‘low’ due to lack of investigator, participant and outcome assessment, blinding and indirectness of comparison, which prevented pooling of results [Table 2].

Taken together, our findings suggest moisturizer marginally improves atopic dermatitis severity by relieving patient’s subjective illness rather than the objective signs.

Quality of life

Giordano-Labadie et al. and Tiplica et al. have shown that moisturizer users experienced greater, but marginal, score changes in children’s dermatology life quality index and patient-oriented eczema measure compared to control (Giordano-Labadie et al.: –0.8 ± 0.4; P=0.001 and –0.4 ± 1.5; P=0.172, accordingly; and Tiplica et al.: Dexeryl® -3.23 ± 0.10; Atopiclair® -2.00 ± 0.10; no moisturizer 0.72 ± 0.11).30,33 On the other hand, Grimalt et al. have shown no significant differences in Infant’s Dermatitis Quality of Life Index scores between treated and control groups (P=0.131).31 Similar to other outcomes, we assessed the GRADE quality as ‘very low’ due to high risk of bias, conflicting individual results and differences in scoring system used [Table 2].

Discussion

Although moisturizers are widely recommended in paediatric atopic dermatitis, most studies that illustrate their efficacy utilize designs where moisturizers of interest were compared to a placebo/vehicle, as opposed to a no moisturizer control, which reflects the indirectness of comparison.7,9,10,20-24 Therefore, we aimed to evaluate moisturizer against a no treatment group to clearly assess its efficacy in the young.11

Our primary outcome shows that moisturizer grants an additional two-week extension of flare-free period in children. The protective effect during the first month of latency is greatest compared to subsequent months, with a remaining 47% risk reduction by the third month. Our findings reveal a lower moisturizer efficacy compared to that of van Zuuren et al., in which their pooled result from all ages showed a 60% risk reduction (2 randomised controlled trials, n=87, pooled risk ratio 0.4 and 95% confidence interval 0.23–0.7, I2 0%) at six months of latency.11 Similarly, we have shown that children were 2.7 times more likely to experience a three to six months remission, but van Zuuren et al. has demonstrated a magnitude of 3.74 times from pooling 2 randomised controlled trials with duration of six months (n=87, 95% confidence interval 1.86 to 7.5, I2 0%).11 While the previous results included fewer studies and smaller sample sizes, age-related variation could also explain the lower magnitudes of efficacy in our study. This is because children may inherently have a more active disease progression compared to adults, thus ultimately reflecting diminished effect of moisturizers in this age group.11 In addition, moisturizer relieved pruritus and xerosis, but not objective signs. This is consistent with previous studies suggesting its primary role in relieving subjective symptoms.11,13,35 However, their benefits may be too marginal to confer clinical significance, as pooled SCORAD change (3.46 points) did not meet the reported minimal clinically important difference of 8.7, a finding comparable to a 2.42 points reduction from the previous meta-analysis.11,36 Due to conflicting results and lack of a fixed scoring system, it is difficult to conclude that moisturizers improve quality of life. Based on our findings, its benefits may be minimal in practice, considering the score changes in Giordano-Labadie et al. and Tiplica et al., which do not meet the corresponding minimal clinically important differences for CDLQI and patient-oriented eczema measure (2.5 and 3.4, respectively).30,33,36,37 This is in line with results from van Zuuren et al. that also demonstrated no significant improvement in quality of life scores (2 randomised controlled trials, n=177, standardised mean difference: 0.15, 95% confidence interval: 0.55–0.24, I2=42.19%).11

The efficacy of moisturizer remains inconclusive as evident from the GRADE certainty assessment. Included studies demonstrated serious risk for bias due to lack of participant, researcher and outcome assessment blinding, which could have affected investigators’ judgment in confirming new flares: the main determinant of result validity. Publication bias was likely to be present as only a limited number of small-scale randomised controlled trials on this topic were published. Negative results from long-term follow-ups may not proceed to publication, which accounted for the presence of mostly short duration trials. Therefore, with only 2-4 studies contributing to the major findings, our result lacks generalization. Indirectness was due to differences in study design, especially in Giordano-Labadie et al., Grimalt et al. and Tiplica et al., which allowed the use of topical corticosteroid.30,31,33 Thus, the efficacy of moisturizer may be overestimated in these studies.26,28 Imprecision was mainly due to limited sample sizes and wide confidence intervals. Similar to limitations faced by the previous meta-analysis, our findings must be interpreted with great caution due to little confidence in the effect estimates.11

Limitations

There is a dire need to conduct randomised controlled trials with more robust and standardised designs. We propose that future trials must: (1) include blinding of participant, investigator and outcome assessments; (2) recruit larger sample sizes with longer follow-up periods beyond six months because moisturizers are safe;11(3) provide details on the level of care (i.e. community clinic and secondary care) and time of the year/season in which participants were recruited, as these crucial factors impact how moisturizers are prescribed and used, to ensure improved result generalizability;38,39 (4) control the strength of topical corticosteroid used between trials or avoid them entirely if the main goal is to assess moisturizer efficacy; (5) utilize a universal scoring system for each outcome to ensure directness and allow inter-trial comparison and quantitative synthesis and (6) further assess minimal clinically important differences for each scoring system, as these values determines the applicability of the product in real-life practices. Not until high quality randomised controlled trials are available could we conclude the efficacy of moisturizer in paediatric atopic dermatitis.

Conclusion

Moisturizers are effective at prolonging remission and reducing risk of relapse but may have limited efficacy in improving disease severity and quality of life in paediatric atopic dermatitis. Despite our findings, high quality randomised controlled trials with standardised designs are warranted to confirm the effectiveness of moisturizers in the young.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Section 1. Diagnosis and assessment of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:338-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- How atopic is atopic dermatitis? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114:150-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life of children with atopic dermatitis and their families. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2008;8:228-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in children and adults: European academy of allergology and clinical immunology/American academy of allergy, asthma and immunology/ PRACTALL consensus report. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118:152-69.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Current guidelines for the evaluation and management of atopic dermatitis: A comparison of the joint task force practice parameter and American academy of dermatology guidelines. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139:S49-57.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Section 2. Management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: Section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:327-49.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emollients and moisturisers for eczema. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;2:CD012119.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Non-prescription treatment options. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2017;1027:121-37.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrier repair therapy in atopic dermatitis: An overview. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:389-99.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moisturizers: The slippery road. Indian J Dermatol. 2016;61:279-87.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000100.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The U.K. working party's diagnostic criteria for atopic dermatitis. I. Derivation of a minimum set of discriminators for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131:383-96.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The cochrane collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2013. GRADE Working Group. Available from: http://www.gdtguidelinedevelopmentorg/app/handbook/handbookhtml [Last accessed 2020 Dec 15]

- [Google Scholar]

- The economics of topical immunomodulators for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. Pharmacoeconomics. 2005;23:543-66.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient-reported outcomes from a multicenter, randomised, vehicle-controlled clinical study of MAS063DP (atopiclair) in the management of mild-to-moderate atopic dermatitis in adults. J Dermatolog Treat. 2008;19:327-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MAS063DP is effective monotherapy for mild to moderate atopic dermatitis in infants and children: A multicenter, randomi, vehicle-controlled study. J Pediatr. 2008;152:854-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long-term emollient therapy improves xerosis in children with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28:1456-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A double-blind, randomized, vehicle-controlled clinical study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of MAS063DP (ATOPICLAIRTM) in the management of atopic dermatitis in paediatric patients. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2008;19:619-25.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intermittent dosing of fluticasone propionate cream for reducing the risk of relapse in atopic dermatitis patients. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:528-37.

- [Google Scholar]

- Randomised controlled trial of short bursts of a potent topical corticosteroid versus prolonged use of a mild preparation for children with mild or moderate atopic eczema. BMJ. 2002;324:768.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comparative trial of 5% dexpanthenol in water-in-oil formulation with 1% hydrocortisone ointment in the treatment of childhood atopic dermatitis: A pilot study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11:366-74.

- [Google Scholar]

- Twice-weekly topical corticosteroid therapy may reduce atopic dermatitis relapses. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:1151-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of a new emollient-based treatment on skin microflora balance and barrier function in children with mild atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33:165-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of a new moisturizer (Exomega milk®) in children with atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Treat. 2006;17:78-81.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The steroid-sparing effect of an emollient therapy in infants with atopic dermatitis: A randomized controlled study. Dermatology. 2007;214:61-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prolonging time to flare in pediatric atopic dermatitis: A randomized, investigator-blinded, controlled, multicenter clinical study of a ceramide-containing moisturizer. Adv Ther. 2017;34:2601-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prevention of flares in children with atopic dermatitis with regular use of an emollient containing glycerol and paraffin: A randomized controlled study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:282-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steroid-free over-the-counter eczema skin care formulations reduce risk of flare, prolong time to flare, and reduce eczema symptoms in pediatric subjects with atopic dermatitis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2015;14:478-85.

- [Google Scholar]

- Non-prescription treatment options In: Fortson EA, Feldman SR, Strowd LC, eds. Management of Atopic Dermatitis: Methods and Challenges. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 2017. p. :121-37.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EASI, (objective) SCORAD and POEM for atopic eczema: Responsiveness and minimal clinically important difference. Allergy. 2012;67:99-106.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical experience and psychometric properties of the children's dermatology life quality index (CDLQI), 1995-2012. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:734-59.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seasonal variation and monthly patterns of skin symptoms in Korean children with atopic eczema/dermatitis syndrome. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2017;38:294-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cost and effectiveness of prescribing emollient therapy for atopic eczema in UK primary care in children and adults: A large retrospective analysis of the clinical practice research datalink. BMC Dermatol. 2018;18:9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]