Translate this page into:

Etiology of pyrexia in pemphigus patients: A dermatologist's enigma

2 Research Centre of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine; Department of Medical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, I.R. Iran

3 Research Centre of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine; Department of Infectious Diseases, Faculty of Medicine, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, I.R. Iran

4 Department of Medical Biochemistry and Clinical Laboratories, Faculty of Medicine, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, I.R. Iran

Correspondence Address:

Alka Hasani

Research Centre of Infectious Diseases and Tropical Medicine and Department of Medical Microbiology, Faculty of Medicine, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz

I.R. Iran

| How to cite this article: Qadim HH, Hasani A, Zinus BM, Orang NJ, Hasani A. Etiology of pyrexia in pemphigus patients: A dermatologist's enigma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2012;78:774 |

Sir,

Pemphigus vulgaris (PV) is a rare immunobullous dermatosis with worldwide distribution. The core manifestation of the condition is mucosal erosions and easily ruptured bullae that emerge on an apparently normal skin and mucous membranes or on an erythematous base. It is perhaps the most formidable dermatologic emergency which requires prompt treatment without which it may prove to be fatal. Though, new treatment modalities have decreased the mortality, nevertheless complications of the treatment are the main hazards presented by various clinical manifestations, and among them fever represents one of the most important presentations. [1]

To characterize pyrexia, seventy two febrile pemphigus cases admitted to dermatology ward of a University Teaching Hospital, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, Tabriz, Iran, were enrolled in this study, during March 2010 to February, 2011. The patients received oral therapy (oral prednisolone 1-2 mg/kg/day) and cytotoxics including azathioprine and cyclophosphamide or pulse therapy (with methyl prednisolone 500-1000 mg daily for three days and cyclophosphamide 500 mg with MESNA [2 Mercapto Ethane Sulfonate Sodium] rescue). Investigations for the management of fever included blood, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), urine, cutaneous lesions and synovial fluid culture, gram′s and AFB (Acid Fast Bacilli) staining of sputum, complete blood count (CBC), erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), chest X-ray and stool examination for ova or cyst of parasites. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 16.

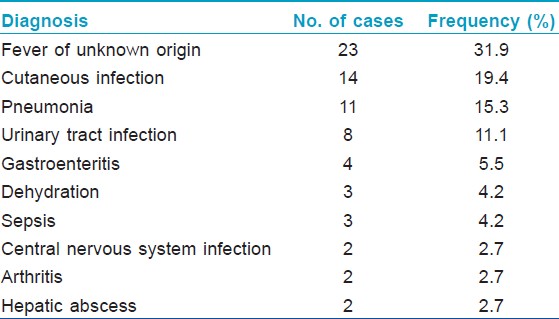

Among 72 febrile pemphigus patients admitted, majority (97.2%) of them were classified as pemphigus vulgaris, with suprabasal acantholysis, while only 2.8% cases presented with pemphigus foliaceous, with more superficial (subcorneal) acantholysis. Though not significant, 56.9% of patients were females. Mean age of cases was 45.31 ± 16.75. Mean interval since diagnosis of pemphigus (and initiation of treatment) to the presence of fever was 5.72 ± 4.97 days. Oral therapy was prescribed to 91.7% of patients, while 8.3% received pulse therapy. The prime etiology of pyrexia was the presence of infection at various sites including: cutaneous lesions (19.4%), pulmonary infections (15.27%), urinary tract infections (11.1%) and gastroenteritis (5.5%) [Table - 1]. No patient was found positive for the presence of mycobacterium morphology on AFB smear of sputum. Staphylococcus aureus infection was revealed in 82.9% of cases with cutaneous erosions.

Pemphigus vulgaris, an immunobullous dermatosis, is one of the common dermatologic disorders. Patient may perceive fever during treatment with steroid and cytotoxics or before treatment. This is the first report on febrile illness in pemphigus patients from North West, Iran. A study conducted on pemphigus patients in Kuwait accounted bacterial cutaneous infections as the most common predisposing factor, [2] while eroded skin infections (24%) were reported in other surveys. [3],[4] Almost 19% of our hospitalized patients had fever as a complication due to ulceration of the skin. In our study only three (4.16%) cases were found to develop fever due to sepsis, while a clinical survey conducted in 2001 reported septicemia to be the most common cause of fever. [5] Amongst our febrile patients, etiology could not be established in 31.9% of cases and thus were characterized as patients with fever of unknown origin (FUO). Development of arthritis (23%) and pneumonia (20%) have been found as the most common predisposing factors in an another study. [6] Around 15% of our cases having pneumonia presented with fever and two patients were observed to have arthritis and also had developed fever. According to the literature, drug induced pyrexia and adrenal insufficiency must be considered in immunosuppressed patients such as those receiving steroids or with noninfectious conditions including malignant neoplasm. [7] Nevertheless, there was no evidence of malignant neoplasm or adrenal insufficiency in our patients based on investigations. Furthermore, we also considered azathioprine as a risk factor for fever and even modified drug regimen in these cases. Connective tissue disorders are a cause of classical FUO and since pemphigus vulgaris, itself has an autoimmune base, it made us to focus on all of our patients for lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis and other disorders, however no case was found positive. Cutaneous and pulmonary infections rates were lower than FUO with 19.4 and 15.27% respectively. Fever in hospitalized pemphigus patients may be due to various predisposing factors, which may be fatal and lead to high mortality rate. Pemphigus is a lethal disease with patients receiving immunosuppressive treatment, thus if patient develops fever, it is suggested that all investigations should be performed to clarify the origin. FUO could be considered when all investigations prove unconstructive. Furthermore, it is suggested that dermatologists should perform investigations repeatedly with respect to the clinical developments.

Acknowledgement

We wish to thank all nursing staff and the patients for their cooperation in carrying out this work. Ms.Leila Dehghani is being thanked for her excellent microbiological efforts.

| 1. |

Raychaudhuri SP, Siu S. Pneumocystis carini pneumonia in patients receiving immunosuppressive drugs for dermatological disease. Br J Dermatol 1999;141:528-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Alsaleh QA, Nanda A, Al-Baghli NM, Dvorak R. Pemphigus in Kuwait. Int J Dermatol 1998;38:351-56.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Cummins DL, Mimouni G, Anhalt GJ. Oral cyclophosphamide for treatment of Pemphigus vulgaris and foliaceous. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;49:276-80.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Ljuboj S, Lipozen J, Brenner S, Budimciæ D. Pemphigus vulgaris: A review of treatment over a 19-years period. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2002;16:599-603.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Aboobaker J, Morar N, Ramidal PK. Pemphigus in South Africa. Int J Dermatol 2001;40:115-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Woldegiorgis S, Swerlick R. Pemphigus in the southeastern United States. South Med J 2001;9:694-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Chans FY, Singh N, Gayowaski T, Wagener MM, Marino IR. Fever in liver transplant receipients: Changing spectrum of etiologic agents. Clin Infect Dis 1998;26:59-65.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

2,514

PDF downloads

2,739