Translate this page into:

Extragenital lichen sclerosus of childhood presenting as erythematous patches

Correspondence Address:

N G Stavrianeas

"Attikon" General University Hospital, 1 Rimini Str., Chaidari, 124 61, Athens

Greece

| How to cite this article: Stavrianeas N G, Katoulis A C, Kanelleas A I, Bozi E, Toumbis-Ioannou E. Extragenital lichen sclerosus of childhood presenting as erythematous patches. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:59-60 |

|

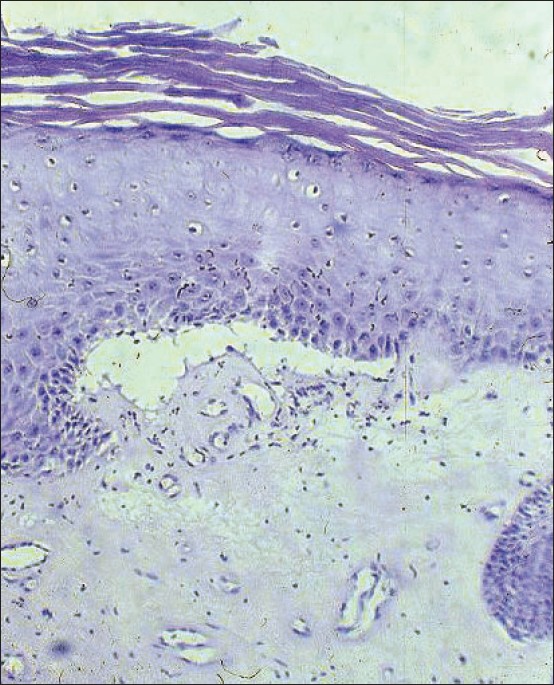

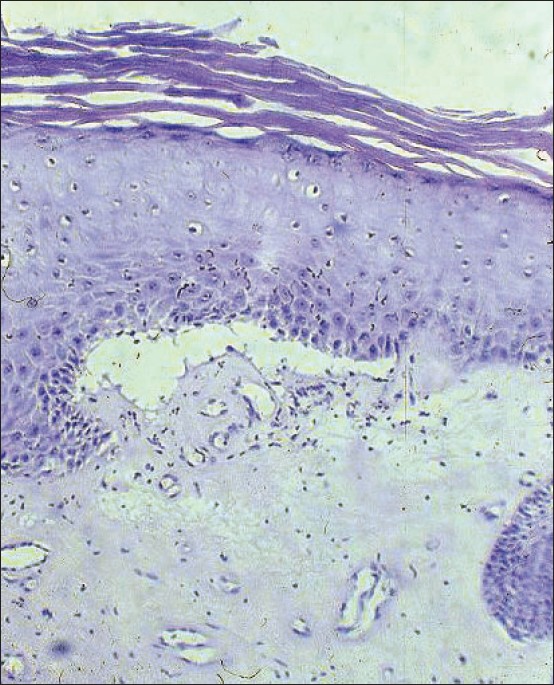

| Figure 2: Epidermal hyperkeratosis, subepidermal clefting and dermal hyalinization with mild lymphohistiocytic infiltration at dermoepidermal junction (H and E, X100) |

|

| Figure 2: Epidermal hyperkeratosis, subepidermal clefting and dermal hyalinization with mild lymphohistiocytic infiltration at dermoepidermal junction (H and E, X100) |

|

| Figure 1: Hypopigmented sclerotic areas and erythematous lesions coexisting in the same area |

|

| Figure 1: Hypopigmented sclerotic areas and erythematous lesions coexisting in the same area |

Sir,

Lichen sclerosus (LS) originally described by Hallopeau in 1887, is a chronic inflammatory dermatosis of obscure etiology. It is rather a rare mucocutaneous disorder that predominantly affects the genitoanal area with white porcelain-like sclerotic lesions. [1] Its incidence peaks in early childhood and after menopause. [2] Lichen sclerosus occurs in childhood with genital and/or extragenital involvement.

A nine-year-old Caucasian Greek girl presented to our department with asymptomatic ill-defined erythematous lesions of the trunk and thighs. On clinical examination we observed multiple confluent red patches, approximately 1-2 cm in diameter, which had appeared two weeks previously. The genital organs and the oral cavity were without lesions. No lymph nodes were palpable. Her physical examination was otherwise normal. The patient was not on any medication. Her medical and family history was negative for skin diseases. A punch biopsy from a trunk lesion was performed. The histopathological findings were not diagnostic showing hyperkeratosis, dilated capillaries and moderate perivascular lymphocytic inflammatory infiltrate. The patient was treated with a potent topical corticosteroid for three weeks with no significant improvement.

At five months after onset, some of the lesions became hypopigmented sclerotic plaques while others remained erythematous. There were areas where sclerotic and erythematous lesions coexisted [Figure - 1]. Mucous membranes remained unaffected. A second punch biopsy from the lumbar region was performed. The histopathological findings of the second punch biopsy from a sclerotic plaque showed an epidermis with compact hyperkeratotic scale [Figure - 2]. A cleft-like space separated the epidermis from the pale dermis. Atrophy, hyalinization and homogenization of the dermal collagen and a mild band-like lymphohistiocytic infiltration were also observed. Dilated capillaries were noted. These findings were consistent with lichen sclerosus. Furthermore, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for Borrelia -specific DNA in lesional skin was negative. Antinuclear antibodies were also negative. Finally, all routine blood panels were within normal limits. A potent topical corticosteroid cream was prescribed for 4 weeks. At the 4 week follow-up visit, both erythematous patches and sclerotic plaques remained unchanged. The topical corticosteroid therapy was discontinued and topical pimecrolimus was instituted, twice daily for 6 months. 1 month after initiating treatment with pimecrolimus, skin lesions showed significant regression of both the erythematous and sclerotic component. The patient was assessed at monthly intervals for 12 months and her clinical improvement was sustained during this period. No side-effects were reported. Moreover, no recurrence occurred during the follow-up period.

Lichen sclerosus is uncommon in childhood. An estimated prevalence of at least 1 in 900 was reported. [3] It is most often seen in the anogenital area. Extragenital involvement is even less common. Female to male ratio is 10:1 and it appears more frequently in patients with atopy. [1] In children the onset of symptoms occurs between two to five years of age, although the disease can manifest itself anytime between the ages one to 13 years. Cutaneous LS may exist alone or in association with genital LS in 15-20% of the cases. [2] It can affect any skin site. Lesions consist of asymptomatic white polygonal papules or macules that may coalesce into patches with comedo-like plugs. To our knowledge, this is the first case of extragenital LS of childhood that has initially presented with erythematous skin lesions. The etiology of LS remains unclear. A genetic basis has been suggested, in particular an association with Class I HLA antigens and also with HLA - A29, B44. [4] Other studies have shown an association with human papilloma virus (HPV) or with spirochete, Borrelia. [4] Autoimmune phenomena, hormonal factors and trauma have been implicated in the etiology of the disease. [3] Although considered by some to be localized scleroderma, most agree that LS is a separate entity. However, these two conditions may coexist. [5]

Currently, there is no generally effective treatment available for LS. Most patients are initially treated with potent topical corticosteroids. [6] Various treatments including PUVA, long-wave UVA, topical testosterone and estrogen, topical tacrolimus or pimecrolimus, antimalarial agents, penicillin, topical retinoids and vitamins, have been tried. [6],[7],[8],[9] Our patient responded well to topical pimecrolimus. This is consistent with other reports in the literature. [6],[7],[9] Topical calcineurin inhibitors may represent a safe and effective therapeutic alternative for LS in childhood. Our case is interesting because it is the first report of extragenital LS of childhood that has initially presented with erythematous skin lesions. It is noteworthy that the early lesions of morphea, a condition related to LS, are also erythematous. [5] In addition, we reported five cases of erythematous lesions of nonspecific balanitis in adults that evolved into typical LS of the genitals during the three-year follow up. [10] It can be speculated that an erythematous variant or an early erythematous stage of LS may exist. In conclusion, chronic recalcitrant erythematous skin lesions may herald the onset of LS. Long-term monitoring of such cases is warranted.

| 1. |

Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol 1995;32:392-416.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Powell JJ, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Lancet 1999;353: 1777-83.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Powell J, Wojnorowska F. Childhood vulvar lichen sclerosus: An increasingly common problem. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;44:803-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Purcell KG, Spencer LV, Simpson PM, Helman SW, Oldfather JW, Fowler JF Jr. HLA antigens in lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Arch Dermatol 1990;126:1043-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Glockenberg A, Cohen-Sobel E, Caselli M, Chico G. Rare case of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus associated with morphea. J Am Assoc Podiatr Med 1994;84:622-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Kunstfeld R, Kirnbauer R, Stringal G, Karlhofer FM. Successful treatment of vulvar lichen sclerosus with topical tacrolimus. Arch Dermatol 2003;139:850-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Kreuter A, Jansen T, Stucker M, Herde M, Hoffmann K, Altmeyer P et al. Low-dose ultraviolet-A1 photherapy for lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Clin Exp Dermatol 2001;26:30-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Bohm M, Frieling U, Luger TA, Bonsmann G. Successful treatment of anogenital lichen sclerosus with topical tacrolimus. Arch Dermatol 2003;139:922-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Boms G, Gambichler T, Freitag M, Altmeyer P, Kreuter A. Pimecrolimus 1% cream for anogenital lichen sclerosus in childhood. BMC Dermatol 2004;4:14.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Stavrianeas NG, Katoulis AC, Vareltzidis A, Stratigos JD. Lichen sclerosus heralded by a non-specific erythema of the genitals. Nouv Dermatol 1996;15:77-82.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

4,150

PDF downloads

2,027