Translate this page into:

Forehead plaque: A cutaneous marker of CNS involvement in tuberous sclerosis

Correspondence Address:

G Raghu Rama Rao

Gopal Sadan, D. No.: 15-1-2C, Naoroji Road, Maharanipeta, Visakhapatnam - 530 002

India

| How to cite this article: Rama Rao G R, Krishna Rao P V, Gopal K, Kumar Y H, Ramachandra B V. Forehead plaque: A cutaneous marker of CNS involvement in tuberous sclerosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:28-31 |

Abstract

Background: Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is a neurocutaneous genodermatosis characterized by hamartoma formation in multiple organs. There are no definite cutaneous markers suggestive of central nervous system (CNS) involvement in TSC. Aims: To study association of forehead plaque seen in tuberous sclerosis patients and CNS involvement in TSC. Methods: This is a retrospective study of 15 cases of tuberous sclerosis in varying age groups - from 1.5 to 50 years. All the cases were thoroughly evaluated with detailed history; clinical examination; and relevant investigations like X-rays of chest, skull, hands and feet; ultrasound abdomen and computed tomography of brain. Results: Out of the 15 cases, CNS involvement was seen in 8 cases. Seizures were present in 8 cases (53.33%) and mental retardation was seen in 6 cases (40%). Computerized tomography of brain revealed subependymal nodules (SENs) in eight cases (53.33%). In addition to SENs, subependymal giant cell astrocytomas and cortical tubers were seen in 2 cases each. Out of these 8 cases having CNS involvement, in 7 cases forehead plaque was observed. In 1 case, no forehead plaque was observed (X 2 = 1.07, P <0.05). Conclusion: This study shows that there is a statistically significant relationship between the presence of a forehead plaque and CNS involvement in TSC. Therefore, forehead plaque may be considered as a novel cutaneous marker to know the CNS involvement in TSC at an early stage.

|

| Figure 4: Retinal phakoma |

|

| Figure 4: Retinal phakoma |

|

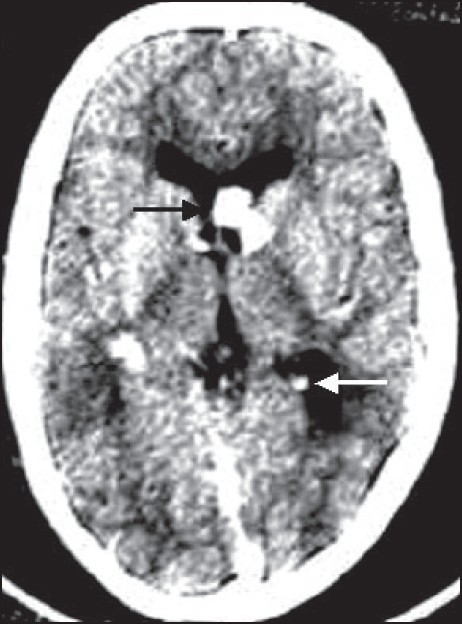

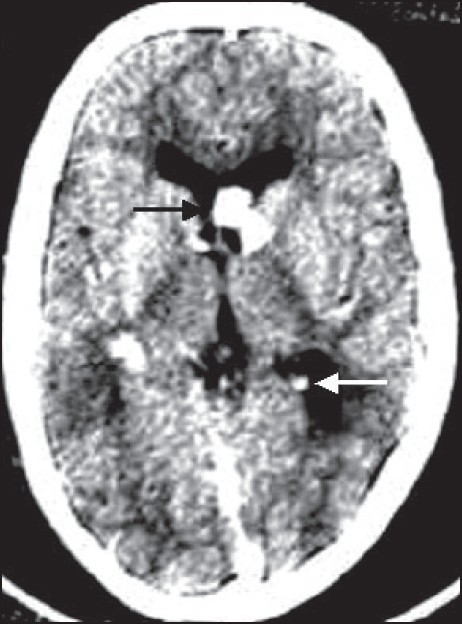

| Figure 3: Subependymal nodule (white arrow) and subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (black arrow) |

|

| Figure 3: Subependymal nodule (white arrow) and subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (black arrow) |

|

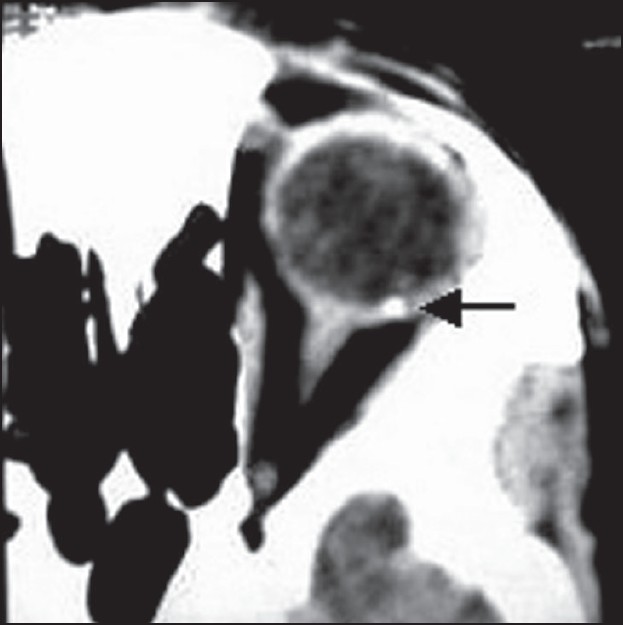

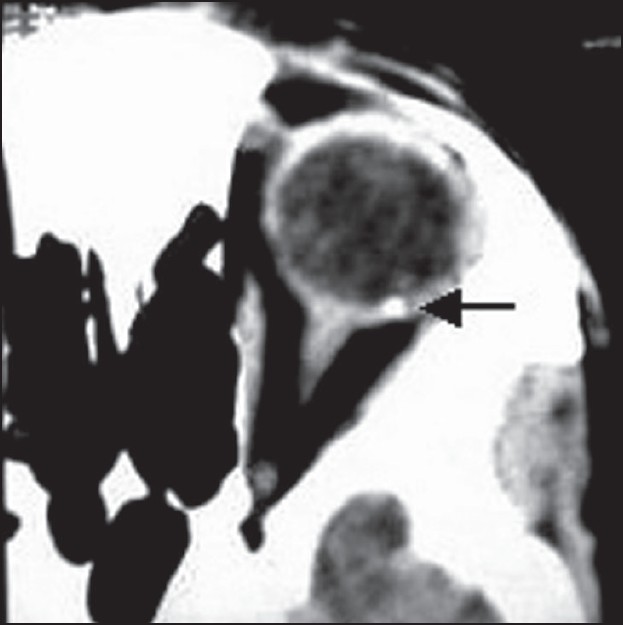

| Figure 2: Multiple forehead plaques |

|

| Figure 2: Multiple forehead plaques |

|

| Figure 1: Single forehead plaque |

|

| Figure 1: Single forehead plaque |

Introduction

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is an autosomal dominant neurocutaneous genodermatosis characterized by hamartoma formation in multiple organs - like skin, brain, kidney, lung, heart and eyes. [1],[2],[3] The incidence of TSC is about 1 in 10,000, with half of the TSC families linked to chromosome 9q34 and the other half to 16p13. Tuberin (TSC1) and hamartin (TSC2), proteins having tumor-suppressor activity, located on chromosomes 9 and 16 respectively are the known defective proteins in TSC. [4],[5] Approximately 60% of cases occur as apparent sporadic cases without any family history, due to germline mosaicism. [6] The definitive diagnosis of TSC is made by the presence of either one primary feature like facial angiofibromas, subungual fibromas, cortical tubers, etc.; or two secondary features or one secondary plus two tertiary features. [2],[7]

CNS manifestations like seizures occur in 86%, mental retardation in 49% and cutaneous manifestations are seen in almost 96% patients of TSC. [5],[8] Cutaneous manifestations of TSC include facial angiofibromas, subungual fibromas, hypomelanotic macules, forehead fibrous plaques and shagreen patches. [2],[7],[9] In 1961, Nickel and Reed observed fibromatous forehead plaques in patients with advanced mental retardation. They opined that presence of fibrotic forehead plaque was a poor prognostic sign in tuberous sclerosis. [10] Till now, there are no specific studies to observe the relationship between forehead plaque and CNS manifestations. The objective of the present study is to examine the relationship between the presence of forehead plaque and CNS involvement in TSC.

Methods

This retrospective study was conducted in the Department of Dermatology, King George Hospital and Andhra Medical College, Visakhapatnam, between May 2003 and October 2004. The study group included 15 cases of tuberous sclerosis. Diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis was made on the basis of the presence of at least one primary feature, which included facial angiofibromas, multiple subungual fibromas, cortical tubers, subependymal nodules or giant cell astrocytomas and multiple retinal astrocytomas. [2],[7]

In all patients, a detailed clinical history was taken with reference to age at onset of various cutaneous lesions, infantile spasms, seizures or mental retardation. Family history was taken in all patients, including details of any affected first-degree relative, consanguinity and genetic pedigree. In all patients, thorough dermatological and CNS examination was carried out. Complete ophthalmologic examination was also done in all patients with direct and indirect ophthalmoscopy and fundoscopy to detect any retinal hamartomas. In all 15 cases, computed tomography of brain was performed to find out any CNS lesions.

Relevant investigations like routine hematological and biochemical tests; X-rays of the chest, skull, hands and feet; and ultrasound abdomen were performed. Elliptical biopsy of the forehead plaque was done in seven patients to study the histopathological features.

Results

Out of the 15 TSC patients, 8 were males and 7 were females. The age of the patients varied from 1.5 years to 50 years. Mean age was 15.9 years. Seven of the 15 patients gave a family history of TSC, with at least one affected first-degree relative. Consanguinity of parents was found in 3 cases.

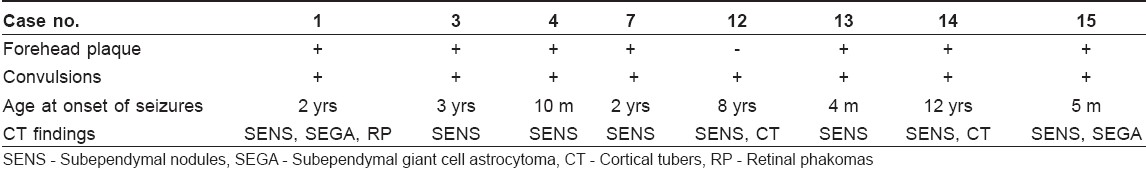

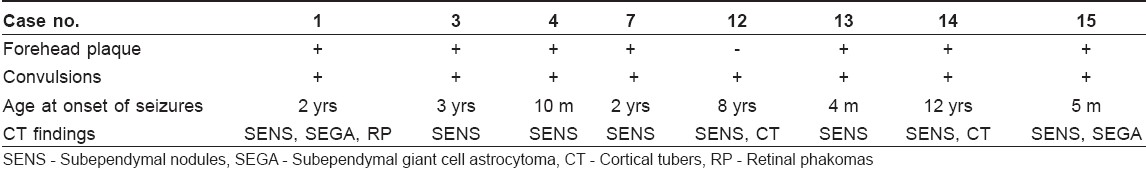

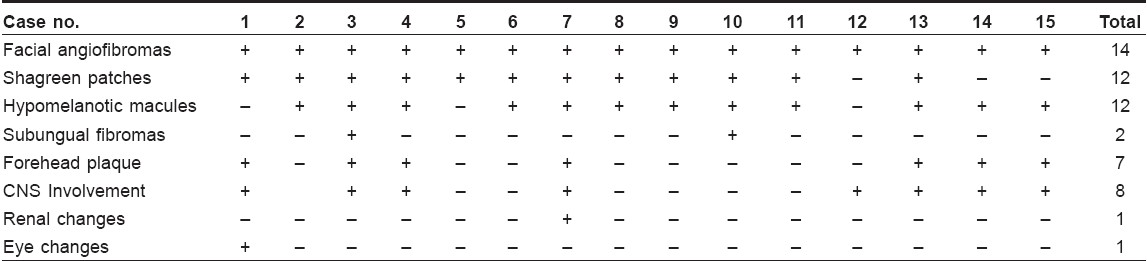

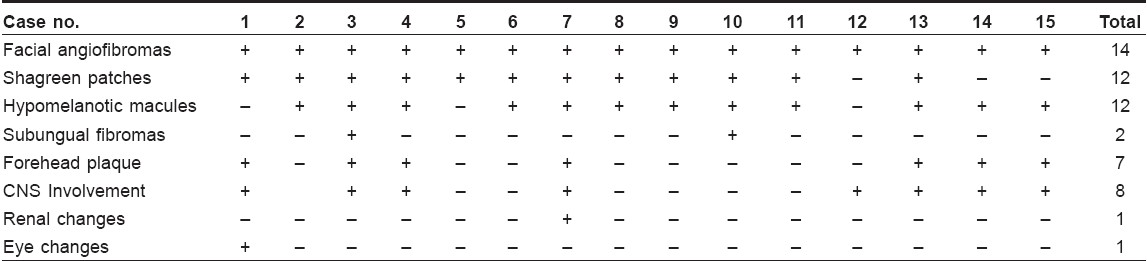

The various clinical features of our cases are given in [Table - 1]. Forehead plaque was observed in 7 of the 15 cases (47%). In 4 cases, a single forehead plaque was present since birth [Figure - 1]. In the 3 other cases, two or more forehead plaques were present, which developed at the age of 2, 3 and 4 years respectively [Figure - 2]. Histopathological examination of the forehead plaques revealed features suggestive of connective tissue hamartoma consisting of vascular, fibrous and dermal tissues.

Specific CNS manifestations and their relationship with forehead plaque are shown in [Table - 2]. Out of the 15 cases, CNS involvement was seen in 8 cases. History of seizures was present in 8 of the 15 cases (53.33%). Out of these 8 cases, 3 cases had infantile spasms; and in 6 cases, mental retardation was observed. CT scan of brain revealed subependymal nodules (SENs) in 8 of the 15 cases (53.33%) [Figure - 3] In addition to SENs, subependymal giant cell astrocytomas and cortical tubers were seen in 2 cases each and retinal phakomas were seen in 1 case [Figure - 4]. Out of these 8 cases having CNS involvement, in 7 cases forehead plaque was observed (χ2 = 1.07, P < 0.05). In 1 case, no forehead plaque was observed. In the remaining 7 cases, neither CNS involvement nor fibrotic forehead plaque was seen.

Routine hematological, biochemical investigations and X-ray studies were within normal limits in all patients. Ultrasound scanning of the abdomen revealed renal angiomyolipomas and distal aortic aneurysm in Case 7.

Discussion

The systemic nature of tuberous sclerosis was first described by Vogt in the clinical triad of seizures, mental retardation and adenoma sebaceum, all of which are not consistently present in all cases. [11] TSC is usually classified as one of the phakomatoses or neurocutaneous syndromes, a group which includes more than 50 entities. [1],[12] It is differentiated from the other members of the group by its involvement of nearly all organ systems and tissues. [1],[2] Pathologically, it is a disorder of cellular migration, proliferation and differentiation. [13]

The cutaneous manifestations of TSC are hypomelanotic macules, confetti skin lesions, facial angiofibromas, ungual fibromas, shagreen patches and forehead plaque. The last four of these provide strong support for a diagnosis of TSC. [2],[5],[7] According to Jozwiak S et al., hypopigmented macules were the most frequent finding (97.2%) and facial angiofibromas were the next common cutaneous lesion. [14] Forehead plaques were observed in 20 of 103 cases (18.9%). Webb et al. , reported forehead plaque in 36% of cases. [15] In our study, in 47% of cases of TSC, forehead plaque was observed. Fibrotic forehead plaques are large connective tissue hamartomas that are fibromatous, soft, compressible, doughy-to-firm tumorous or plaque-like lesions commonly present on the forehead, eyelids, upper cheeks and scalp. These are present in up to 25% of patients with TSC, are often multiple, and are commonly seen on the forehead. [10],[16] Recently, it was found that forehead plaques are more frequently seen in TSC2 patients than in TSC1 patients. [17] The individual lesions tend to be much larger than the angiofibromas on the face, are often unilateral and may be present at birth.

Nickel and Reed in 1961 had observed that in tuberous sclerosis, fibromatous forehead plaque was not observed in normal patients but was common in hospitalized patients with advanced mental retardation. They suggested that the presence of forehead plaque was a poor prognostic sign. [10] Since then, no attempts have been made to establish the association between forehead plaque and CNS involvement. In various previous studies, though forehead plaque was observed, no correlation between these lesions and CNS involvement was made. [8],[9],[14],[15],[18],[19],[20] In one study, forehead plaque along with retinal phakomas and multiple intracranial periventricular calcifications was reported. [20] In our study, various CNS manifestations like infantile spasms, persistent seizures, mental retardation, subependymal nodules, subependymal giant cell astrocytomas, cortical tubers and retinal phakomas were seen in 8 of the 15 cases (53.33%); and in 7 of these cases, forehead plaque was observed (χ2 = 1.07, P < 0.05). In the remaining 7 cases, though other cutaneous manifestations like angiofibromas, shagreen patches and subungual fibromas were seen, no clinical or radiological evidence of CNS involvement was seen. Our findings show that there is a significant relationship between the presence of forehead plaque and CNS involvement. Therefore, whenever fibrotic forehead plaques are seen in TSC patients, a thorough radiological search may be carried out to rule out the involvement of other organ systems, especially CNS, even in the absence of clinical manifestations.

We suggest that forehead plaque can be considered to be a novel cutaneous marker of CNS involvement at an early stage so that proper and timely prophylactic measures can be undertaken to prevent seizures, mental retardation and permanent CNS damage. However, larger clinical studies are warranted to establish forehead plaque as one of the important prognostic markers.

| 1. |

Gomez MR. Tuberous sclerosis. In : Gomez MR, editor. Neurocutaneous diseases. Butterworths: Boston; 1987. p. 30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Kwiatwoski DJ, Short MP. Tuberous sclerosis. Arch Dermatol 1994;130:348-54.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Monaghan HP, Krafchik BR, MacGregor DL, Fitz CR. Tuberous sclerosis complex in children. Am J Dis Child 1981;135:912-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Nijhawan A, Lyon VB, Drolet BA. Paediatric dermatology Cutaneous markers of malformations and selected syndromes - what do you see, when do you see it and how do you find it? Curr Probl Dermatol 2001;13:249-300.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Paller AS, Goldsmith LA. Tuberous sclerosis complex. In : Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff Klaus, Austen KF, Goldsmith LA, Katz SI, editors. Fitzpatrick's dermatology in general medicine. 6 th Ed. McGraw Hill: New York; 2003. p. 1822-5.

th Ed. McGraw Hill: New York; 2003. p. 1822-5.'>[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Northrup H. Tuberous sclerosis complex: genetic aspects. J Dermatol 1992;19:914-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Harper JL. Genetics and Genodermatoses. In : Champion RH, Burton JL, Burns DA, Breathnach SM, editors. Textbook of dermatology. 6 th Ed. Oxford Blackwell Science: 1998. p. 357-447.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Anisya-Vasanth AV, Satishchandra P, Nagaraja D, Swamy HS, Jayakumar PN. Spectrum of epilepsy in tuberous sclerosis. Neurol India 2004;52:210-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Krishnan SG, Yesudian DP, Jayaraman M, Janaki VR, Raj Boopal JM. Tuberous sclerosis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1996;62:239-41.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Nickel WR, Reed WB. Tuberous sclerosis: Special reference to the microscopic alterations in the cutaneous hamartomas. Arch Dermatol 1962;85:209-26.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Morgan JE, Wolfort F. The early history of tuberous sclerosis. Arch Dermatol 1979;115:1317-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Roach ES. Introduction. In : Roach ES, Miller VS, editors. Neurocutaneous disorders. Cambridge University Press: Cambridge; 2004. p. 1-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Arbiser JL, Brat D, Hunter S, D'Armiento J, Henske EP, Arbiser ZK, et al . Tuberous Sclerosis-associated lesions of the kidney, brain and skin are angiogenic neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;46:376-80.

et al . Tuberous Sclerosis-associated lesions of the kidney, brain and skin are angiogenic neoplasms. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;46:376-80.'>[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Jozwiak S, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK, Michalowicz R, Chmielik J. Skin lesions in children with tuberous sclerosis complex: their prevalence, natural course and diagnostic significance. Int J Dermatol 1998;37:911-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Webb DW, Clarke A, Fryer A, Osborne JP. The cutaneous features of tuberous sclerosis: A population study. Br J Dermatol 1996;135:1-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Fryer AE, Osborne JP, Schutt W. Forehead plaque: A presenting skin sign of tuberous sclerosis. Arch Dis Child 1987;62:292-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Dabora SL, Jozwiak S, Franz DN, Roberts PS, Nieto A, Chung J, et al . Mutational analysis in a cohort of 224 tuberous sclerosis patients indicates increased severity of TSC2, compared with TSC1, disease in multiple organs. Am J Hum Genet 2001;68:64-80.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Jeevan KB, Thappa DM, Narasimahan R. Cutaneous features of tuberous sclerosis: A hospital based study in South India. Indian J Dermatol 2000;45:149-53.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Chou PC, Chang YJ. Prognostic factors for mental retardation in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex. Acta Neurol Taiwan 2004;13:10-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Kumar P, Brindha S, Manimegalai M, Premalatha S. Tuberous sclerosis with interesting features. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1996;62:122-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

5,034

PDF downloads

3,210