Translate this page into:

Glutathione as a skin whitening agent: Facts, myths, evidence and controversies

2 Department of Dermatology and STD, UCMS and GTB Hospital, New Delhi, India

3 Department of Dermatology and STD, MAMC and LN Hospital, New Delhi, India

Correspondence Address:

Sidharth Sonthalia

Skinnocence: The Skin Clinic, C-2246, Sushant Lok-1, Block-C, Gurgaon - 122 009, Haryana

India

| How to cite this article: Sonthalia S, Daulatabad D, Sarkar R. Glutathione as a skin whitening agent: Facts, myths, evidence and controversies. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2016;82:262-272 |

Abstract

Glutathione is a low molecular weight thiol-tripeptide that plays a prominent role in maintaining intracellular redox balance. In addition to its remarkable antioxidant properties, the discovery of its antimelanogenic properties has led to its promotion as a skin-lightening agent. It is widely used for this indication in some ethnic populations. However, there is a dichotomy between evidence to support its efficacy and safety. The hype around its depigmentary properties may be a marketing gimmick of pharma-cosmeceutical companies. This review focuses on the various aspects of glutathione: its metabolism, mechanism of action and the scientific evidence to evaluate its efficacy as a systemic skin-lightening agent. Glutathione is present intracellularly in its reduced form and plays an important role in various physiological functions. Its skin-lightening effects result from direct as well as indirect inhibition of the tyrosinase enzyme and switching from eumelanin to phaeomelanin production. It is available in oral, parenteral and topical forms. Although the use of intravenous glutathione injections is popular, there is no evidence to prove its efficacy. In fact, the adverse effects caused by intravenous glutathione have led the Food and Drug Administration of Philippines to issue a public warning condemning its use for off-label indications such as skin lightening. Currently, there are three randomized controlled trials that support the skin-lightening effect and good safety profile of topical and oral glutathione. However, key questions such as the duration of treatment, longevity of skin-lightening effect and maintenance protocols remain unanswered. More randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials with larger sample size, long-term follow-up and well-defined efficacy outcomes are warranted to establish the relevance of this molecule in disorders of hyperpigmentation and skin lightening.Introduction

A lighter skin tone has been considered a superior trait in most races, especially in women of Asian or African descent who have Fitzpatrick skin types IV–VI. The higher prevalence of pigmentary disorders in these skin types adds to the woes of the patients. In relatively conservative societies such as India, many people are obsessed with the desire for a fair complexion for themselves as well as their spouse. Such traditions motivate the patient to desire fair complexion and sometimes seek it even against their will.

Realizing this growing need for fair skin, many pharmaceutical companies are developing different molecules for skin lightening. A lot is already known about topical depigmenting agents such as hydroquinone, glycolic acid, arbutin, kojic acid, vitamin C, vitamin E and niacinamide, all of which are readily available over-the-counter. The advent of newer depigmenting molecules such as pycnogenol, orchid and marine algae extracts, cinnamic acid, soy, aloesin and Boswellia has offered more topical options. Apart from the local adverse effects of these agents, the important limitation is the localization of their effect to the site of application alone. The quest for systemic skin lightening logically ensued. Agents that have been promoted for this purpose include glutathione, tranexamic acid, l-cysteine peptide, vitamin C, different plant extracts and their combinations.[1]

This review focuses on glutathione as a skin-lightening agent. Aggressive media campaigns about its exaggerated effects as a “skin lightening” agent and over-the-counter availability of this drug have resulted in consumption of improper doses and schedules. These consumers, as well as dermatologists who prescribe oral glutathione for general skin lightening or as an adjuvant for disorders of hyperpigmentation, are often oblivious about its efficacy, dosing and adverse effects. Dermatologists frequently encounter patients who are inclined to self-medicate with glutathione, enticed by the manufacturers' claims. We are expected to intelligently answer queries regarding the efficacy and safety of this drug.

Oral and intravenous glutathione have been available in some countries such as the Philippines for many years. This drug has recently made inroads in other countries including India. Most of the patients who desperately seek fair complexion or a new treatment modality for their refractory facial melanosis are typically internet and social media savvy. They are rich enough to afford expensive treatment. Pharmaceutical companies that manufacture intravenous glutathione have a marketing agenda and pursue dermatologists to administer this drug to such patients. Not surprisingly, the trend of recommending and administering intravenous glutathione has increased within months of it becoming available, despite the potential adverse effects and lack of evidence.

It is important that dermatologists know about glutathione: its efficacy, the mechanism of hypopigmentary effects, pharmacokinetics, evidence-level and safety profile. In this review, we attempt to crystallize these concepts and analyze the current evidence supporting the efficacy of glutathione as an inhibitor of melanization.

Molecular Structure and Function of Glutathione

Glutathione (γ-glutamyl-cysteinylglycine) is a small, low-molecular weight, water-soluble thiol-tripeptide formed by three amino acids (glutamate, cysteine and glycine).[1] It is a ubiquitous compound with a biologically active sulfhydryl group contributed by the cysteine moiety that acts as the active part of the molecule.[2] This sulfhydryl group allows for interaction with a variety of biochemical systems, hence the abbreviation “GSH” for its active form. Glutathione is one of the most active antioxidant systems in human physiology.[3]

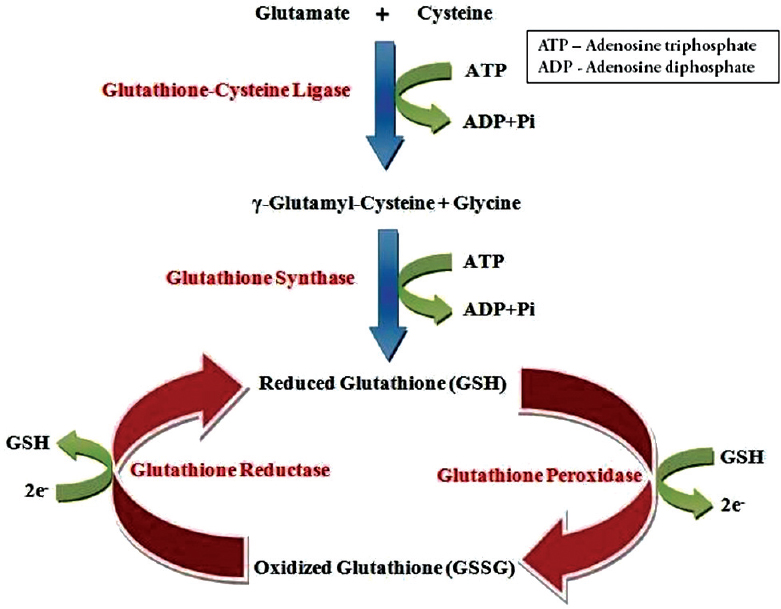

Biological activity: The glutathione redox cycle

Glutathione exists in two interconvertible forms, reduced glutathione (GSH) and oxidized glutathione (GSSG). GSH is the predominant intracellular form, which acts as a strong antioxidant and defends against toxic compounds and xenobiotics. In this process, GSH is constantly oxidized to GSSG by the enzyme glutathione peroxidase [Figure - 1]. To maintain the intracellular redox balance, GSH is replenished through the reduction of GSSG by glutathione reductase enzyme.

|

| Figure 1: The glutathione redox cycle, demonstrating the inter-conversion of oxidized and reduced glutathione |

Biological functions of glutathione

Glutathione plays a key role in multiple biological functions. The most important ones have been enumerated in [Box 1].[4]

Glutathione Depletion and Supplementation in Medical Conditions

Extensive research in various specialties has shown that many human diseases are associated with low glutathione levels. These conditions and causes include emphysema, asthma, allergic disorders, drug toxicity, metabolic disorders, cancer, chemotherapy and human immunodeficiency virus-acquired immune deficiency syndrome, among others.[5],[6] Research on the role of glutathione supplementation in these diseases is limited. Most of the studies have been done for autism and cystic fibrosis.[7],[8]

Glutathione and Human Pigmentation

Melanin in human skin is a polymer of various indole compounds synthesized from L-tyrosine by the Raper–Mason pathway of melanogenesis [Figure - 2] with tyrosinase being the rate limiting enzyme. The ratio of the two different types of melanin found in skin, black-brown colored eumelanin and yellow-red pheomelanin, determines the skin colour.[9] An increased proportion of pheomelanin is associated with lighter skin colour.

|

| Figure 2: The Raper–Mason pathway, depicting the steps in melanin synthesis. Notice how the presence of glutathione/cysteine can induce a switch towards higher pheomelanin production as compared to eumelanin |

Exposure to ultraviolet radiation is the most important factor that causes undesirable hyperpigmentation. The crucial cellular event is enhanced tyrosinase activity. Exposure to ultraviolet radiation results in generation of excessive amounts of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species within the cells.[10],[11] Oral antioxidants partially reduce melanogenesis by suppressing these free radicals.

One of the earliest pieces of evidence of the association between thiols and skin came from the effect of an extract of human skin that contained an active sulfhydryl-containing compound. It prevented melanin formation by tyrosinase inhibition. Hyperpigmentation was observed when this compound got oxidized and inactivated by factors such as heat, radiation and inflammation with consequent loss of the inhibitory effect on tyrosinase. Halprin and Ohkawaraprovided physical and biochemical evidence that this “sulfhydryl compound” was glutathione![12]

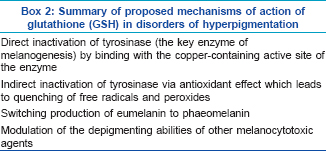

Postulated effects of glutathione on pigmentation

The role of glutathione as a skin-lightening agent was an accidental discovery when skin lightening was noticed as a side effect of large doses of glutathione.[1] Various mechanisms for the hypopigmentary effect of glutathione have been proposed, with inhibition of tyrosinase being the most important [Box 2]. Glutathione can reduce tyrosinase activity in three different ways.[13] Tyrosinase is directly inhibited through chelation of the copper site by the thiol group. Secondly, glutathione interferes with the cellular transfer of tyrosinase to premelanosomes, a prerequisite for melanin synthesis.[13] Thirdly, tyrosinase inhibition is effected indirectly via its antioxidant effect. Glutathione shifts melanogenesis from eumelanin to phaeomelanin synthesis by reactions between thiol groups and dopaquinone leading to the formation of sulfhydryl-dopa conjugates.[14]

Glutathione has potent antioxidant properties. The free radical scavenging effect of glutathione blocks the induction of tyrosinase activity caused by peroxides.[14] Glutathione has been shown to scavenge ultraviolet radiation induced reactive oxygen species generated in epidermal cells.[15] A recent study on melasma patients noted significantly higher levels of glutathione-peroxidase enzyme in patients compared to controls, confirming the role of oxidative stress in melasma.[16] Based on these observations, the potential of glutathione in management of melasma and hyperpigmentation seems plausible.[17]

Natural dietary sources of glutathione

Fresh fruits, vegetables, and nuts are natural sources of glutathione. Tomatoes, avocados, oranges, walnuts and asparagus are some of the most common edibles that help to increase levels of glutathione in the body. Whey protein is another rich source of glutathione and has been used to enhance systemic glutathione levels in cystic fibrosis.[8]

Administration of Glutathione: Pharmaceutical Formulations

Glutathione is primarily available as oral formulations (pills, solutions, sublingual tablets, syrups and sprays) and parenteral formulations (intravenous and intramuscular). It has been administered by intranasal and intrabronchial routes as well. The three major routes of administration used for skin lightening are topical (creams, face washes), oral (capsules and sublingual/buccal tablets) and intravenous injections.

Topical glutathione

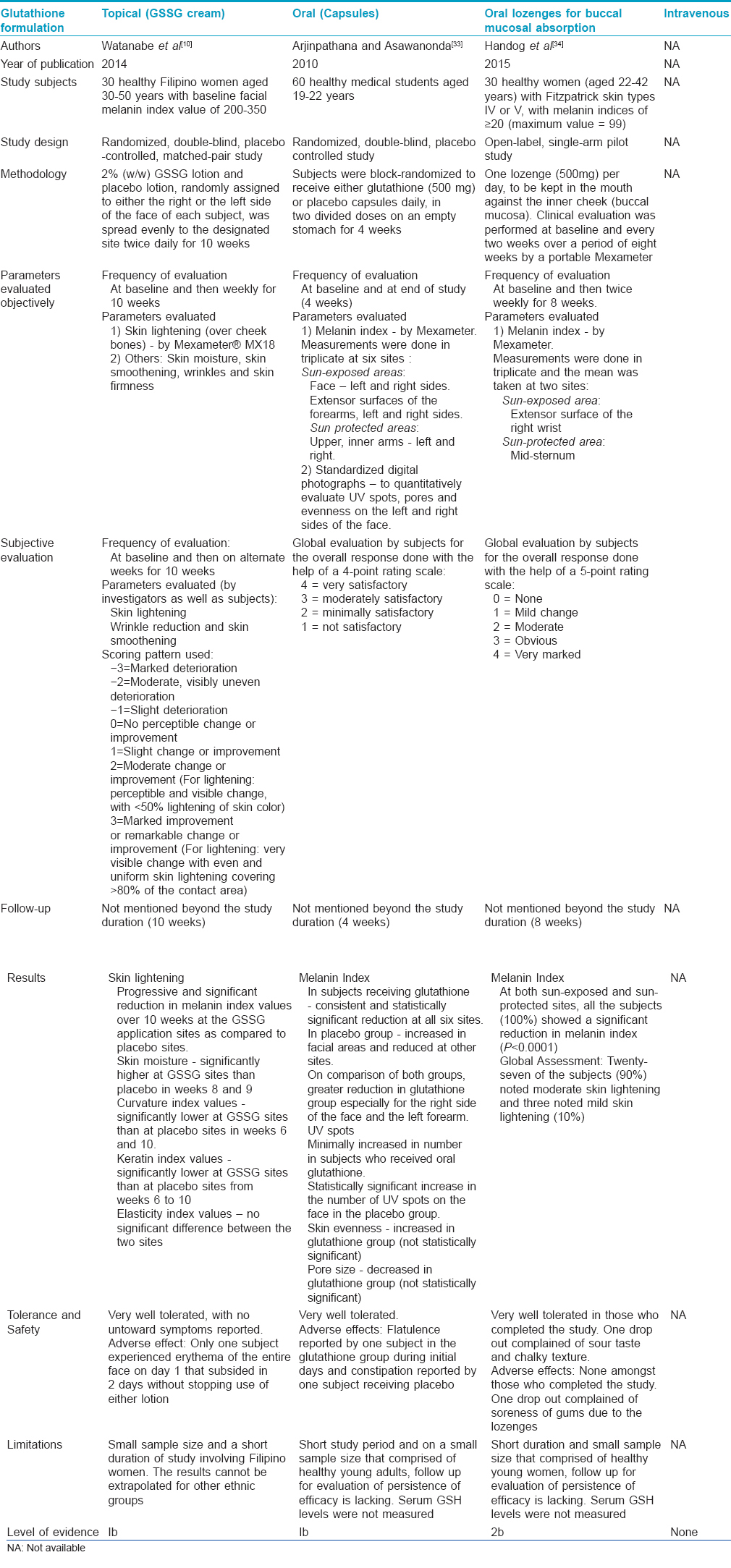

Glutathione is commercially available as face washes and creams. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial conducted in 30 healthy Filipino women aged 30–50 years has provided some evidence favouring the efficacy of topical 2% GSSG lotion in temporary skin lightening. Patients were randomized to apply glutathione as 2% GSSG lotion and a placebo lotion in a split-face protocol, twice daily for ten weeks. GSSG was preferred over GSH, as GSH is unstable in aqueous solutions. GSSG eventually generates GSH after cutaneous absorption. The changes in the melanin index, moisture content of the stratum corneum, skin smoothness, skin elasticity and wrinkle formation were objectively assessed. The reduction of the melanin index with glutathione was statistically significant when compared to placebo [Table - 1].[10] Glutathione treated areas had significant improvement in other parameters as well. No adverse drug effects were reported. Glutathione has also become available in the form of soaps, face washes and creams.[18] Recently, a glutathione based chemical peel has been launched. Although evidence of efficacy is lacking, the manufacturers claim improvement of melasma, hyperpigmentation and skin ageing.[19]

Glutathione mesotherapy

Despite the lack of published literature on the efficacy and methodology of using glutathione solution as mesotherapy, it is widely practiced by dermatologists for the treatment of melasma and other facial melanoses. It is used as monotherapy, or in combination with ascorbic acid, vitamin E, tranexamic acid, etc.[20] Although the results are claimed to be very good, use of glutathione as mesotherapy needs more evidence and published data.

Oral glutathione: Pharmacokinetics and metabolism of orally administered glutathione

Oral glutathione is derived from torula yeast (Candida utilis). It is marketed as a food or dietary supplement, either alone, or in combination with vitamin C, alpha lipoic acid and other antioxidants.

The fate of orally administered glutathione has been studied in animal models and human volunteers. The principal site of absorption is the upper jejunum. Circulating glutathione is primarily cleared by the kidney.[21] Older studies have suggested that glutathione is absorbed intact from the gut. This is based on the observation of lack of similar increase in plasma glutathione levels after the administration of the constituent amino acids of glutathione when compared to the administration of glutathione capsules.[22] After absorption into plasma, glutathione needs to be broken down into amino acids and re-synthesized intracellularly. The administration of cysteine-rich glutathione precursors, especially N-acetyl cysteine, has been shown to increase intracellular glutathione levels.[23]

The bioavailability of oral glutathione in humans is a controversial subject. A single-dose study conducted by Witschi et al. in seven healthy volunteers reported no significant increase in plasma glutathione levels for up to 270 min. However, Hagen and Jones reported an increase in plasma glutathione levels in four out of five subjects after a single oral dose of 15 mg/kg body weight. In that study, the plasma glutathione levels increased to 300% of baseline levels after one hour, followed by a decrease to approximately 200% of baseline levels within the next three hours.[24],[25] The inadequate absorption of glutathione in humans compared to that in rats has been attributed to a higher hepatic gamma-glutamyl transferase activity in humans. This results in increased hydrolysis of glutathione with resultant low serum levels.[21]

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study on oral glutathione supplementation (500 mg twice daily for four weeks) in 40 healthy adult volunteers failed to show any significant change in serum glutathione levels.[26] Another randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled trial was conducted in 54 adults which administered oral glutathione for six months, either in a dose of 250 mg or 1000 mg per day. Results showed a steady increase in glutathione levels when compared to the baseline. There were higher levels in the high-dose group (30–35% increase vs 17% increase in the low-dose group). The raised levels returned to baseline after a one-month washout period.[27] In another study, glutathione administered at a single dose of 50 mg/kg body weight led to a considerable increase of protein-bound glutathione levels in plasma but not of the deproteinized fraction, measured after two hours of supplementation.[28] Since intracellular glutathione levels can increase only after its amino acid components are transported through the cell membrane after deproteinization, the results of this study remain ambivalent.

In summary, human trials performed before 2013 have shown that over-the-counter oral glutathione supplementation has a negligible effect on raising plasma levels in humans. The only trials that support the concept of oral supplementation to raise glutathione levels in healthy adults have been conducted by Richie et al. and Park et al. It is important to take note of the fact that both studies used a specific brand of glutathione, manufactured by the trial funding company.[27],[28] Thus, the evidence for the clinically efficacious bioavailability of oral glutathione in humans remains scarce and controversial.

Oral formulations of glutathione: Manufacturing and processing issues

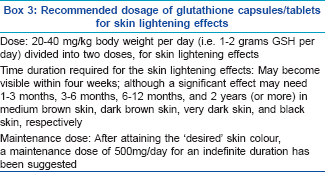

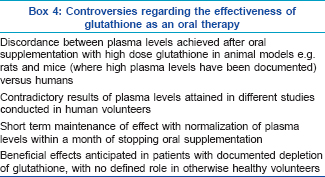

Manufacturing high dose glutathione pills is technically difficult as GSH has a very high electrostatic charge which makes processing and encapsulating higher strengths of glutathione very difficult.[29] Addition of crystalline ascorbic acid dissipates this electrostatic charge and allows packaging of pills with up to 750 mg of the drug.[29] However, oral formulations may have a combination of vitamin C, vitamin E, alpha-lipoic acid, N-acetyl cysteine, grape seed extract, etc. Alpha lipoic acid is a glutathione replenishing disulfide that increases whole blood and intracellular GSH levels.[30] The dosage and duration of oral glutathione has not been standardized with different dosages having been “recommended” by different manufacturers [Box 3].[31] These manufacturer specific guidelines have no clear scientific basis. Oral glutathione is also available as sublingual tablets and solutions. While sublingual preparations contain very low doses (50–100 mg), oral suspensions and solutions have a foul sulfurous taste and need to be freshly prepared.[29] Thus, the controversies regarding the effectiveness of oral glutathione continues to pose a challenge to its prescribers [Box 4].

Statutory approval status of oral glutathione supplements

Glutathione based oral dietary supplements have been granted the status of “Generally recognized as safe”, consistent with Section 201(s) of the federal food, drug and cosmetic act of the United States Food and Drug Administration.[32] There is no restriction on its availability in United States, Philippines and Japan. This has recently become available over-the-counter in India as well.

Evidence-based efficacy of glutathione as an oral-lightening agent

On review of literature, we could find only two studies that evaluated the efficacy of oral glutathione as a skin-lightening agent. A randomized, double-blind, two-arm, placebo-controlled study conducted in the Thai population studied the effect of orally administered glutathione on the skin melanin index in sixty healthy medical students [Table - 1]. The subjects were randomized to receive glutathione capsules in a dose of 500 mg/day in two divided doses, or placebo for four weeks. The primary end-point studied was the reduction of melanin indices at six different sites. At four weeks, the melanin indices decreased consistently at all six sites in the glutathione group. There was a statistically significant reduction at two sites in the placebo group, namely the right side of the face and the sun-exposed left forearm. The tolerance to glutathione was excellent. The limitations of this study include a short study period, lack of follow-up, lack of measurement of serum glutathione levels and the choice of cohort, which consisted of a young and healthy population. Despite these shortcomings, this study was the first to demonstrate the beneficial effects of oral glutathione in skin lightening.[33] Another open-label study that used glutathione containing lozenges reported improvement in the skin melanin index, as measured by Mexameter [Table - 1].[34] Theyused buccal lozenges instead of capsules to enhance and ensure steady bioavailability. In our opinion, the sublingual or buccal route is likely to increase the bioavailability of glutathione better than oral tablets or capsules. A comparative study between these two routes of administration is the only way to provide reliable evidence in this regard.

Intravenous glutathione

Due to the low bioavailability of oral glutathione, intravenous injections are being promoted to provide desired therapeutic levels in the blood and skin and to produce “instant” skin-lightening. Interestingly, intravenous injections of glutathione have been used for years but there is not even a single clinical trial evaluating its efficacy. Manufacturers of intravenous glutathione injections recommend a dose of 600–1200 mg for skin lightening, to be injected once to twice weekly. The duration for which they should be continued is not specified. Intravenous administration is expected to deliver 100% bioavailability of glutathione, much more compared to that achieved by oral administration. However, there are no studies to support this hypothesis. Although intravenous glutathione delivers a much higher therapeutic dose that enhances its efficacy, it also provides a narrower margin of safety due to the possibility of overdose toxicity.

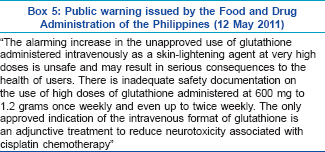

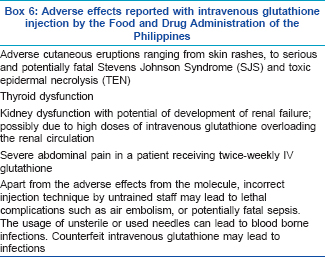

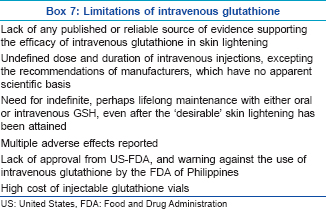

There is no available data on the efficacy of intravenous glutathione for skin lightening. The data on safety are available, but scarce. In an animal-based study, no significant adverse effects were reported in dogs, who were administered up to 300 mg of glutathione per kg body weight every day for 26 weeks.[35] Human studies in which parenteral glutathione was administered for male infertility (600 mg/day glutathione intramuscularly for two months), or given to enhance insulin secretion in people with impaired glucose tolerance, did not report any significant adverse effects.[36],[37] However, the adverse effects of intravenous glutathione have been documented from the Philippines, one of the leading consumers of glutathione. The Food and Drug Administration of Philippines have issued a position paper with a public warning regarding the safety of off-label use of glutathione injection [Box 5] and the adverse drug reactions reported from the use of intravenous glutathione for skin lightening [Box 6].[38] Proponents of intravenous glutathione suggest that these adverse effects may be attributed to other additives present in the glutathione injection vials and the risk is minimized if pure glutathione is used instead.

Another issue pertaining to pure and high-quality intravenous glutathione solution is the extremely high cost. The cheaper versions may be counterfeit, with the risk of life-threatening events. Considering the many limitations of intravenous glutathione, it is prudent that dermatologists refrain from administering such injections for skin lightening until further trials and high quality studies establish a favourable benefit versus risk ratio that justify its use [Box 7]. The recent surge of intravenous glutathione in India has prompted the media and health authorities to spread awareness about its potential complications, although a statutory ban remains elusive.

Other potential adverse effects of glutathione

Since glutathione is a component of human cellular metabolism, the adverse effects seen with oral supplementation are expected to be mild, akin to high-dose vitamin supplements. The adverse effects of intravenous glutathione speculatively arise from the direct delivery of huge amounts of the molecule in the blood circulation. Other potential adverse effects of high dose and long-term glutathione supplementation include:

- Lightening of hair colour: A logically expected effect since hair colour is dependent on the amount and type of melanin which may be altered by glutathione supplementation. This adverse effect has not yet been clinically reported

- Hypopigmented patches, especially on sun-exposed areas have been observed after 10–12 doses of intravenous injection by practitioners (unpublished observations). Their experience suggested that the patchy hypopigmentation tended to resolve after 30-40 doses due to the evolution of a uniform skin-lightening effect

- Depletion of natural hepatic stores of glutathione: Hypothetically, long-term supplementation with any external synthetic compound may signal the body to stop its own production resulting in dependence on synthetic supplements.[39] Depletion of liver glutathione levels (the site of glutathione storage) may be devastating to health. This hypothetical adverse effect, although not clinically reported until now, is analogous to the hypothalamic-pituitary axis suppression seen with long-term use of systemic corticosteroids

- Exacerbation of Helicobacter pylori associated peptic ulcers: Helicobacter pylori is known to feed on macrophages and neutrophils abundant at the site of inflammation caused by the ulcer. As glutathione can improve the numbers and activity of macrophages, peptic ulcers may be exacerbated [40]

- Increased susceptibility to melanoma: Theoretically, long-term administration of systemic glutathione switches eumelanin to pheomelanin, and may increase the susceptibility towards development of melanoma in the long run.[28]

Summary of the role of glutathione as a skin-lightening agent

While there is no published data for intravenous glutathione, the results of the three randomized controlled trials mentioned above have provided grade Ib and 2b evidence in favour of the skin-lightening effects of topical and oral glutathione, with no significant adverse effects [Table - 1]. However, larger and long-term studies are warranted to generate more evidence.

Role of glutathione in disorders of hyperpigmentation

At present, there are no publications that document improvement in any specific hyperpigmentation disorder with the use of topical or oral glutathione. The new-fangled concept of recommending glutathione as an adjuvant (orally, topically or as mesotherapy) for melasma, freckles and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation is based on its depigmenting properties detailed in [Box 2]. In a study that was conducted to evaluate the role of oxidative stress in melasma, the levels of glutathione peroxidase enzyme activity and other pro-oxidant parameters were significantly higher in the blood of patients compared to controls. This confirmed the role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of melasma.[16] Glutathione-peroxidase depletes the serum levels and cellular levels of glutathione. Thus, supplementation of glutathione is logically expected to downregulate melanogenesis and improve melasma. Based on the current level of evidence, other authors have also suggested the use of oral or topical glutathione as an adjunctive therapy for facial melanosis.[1],[41] Further, topical compositions containing S-acyl glutathione (about 0.1–10% by weight) or S-palmitoyl glutathione (about 3–9% by weight) admixed with other depigmenting and anti-oxidant substances have been prepared. They are awaiting grant of a patent by the US Food and Drug Administration to be used for the treatment of melasma, freckles, lentigines and postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.[42] However, one should note that glutathione mainly affects the melanin indices and ultraviolet spots in the sun-exposed areas. It only affects new melanogenesis and not pre-existing pigmentation.[28]

Role of glutathione in skin disorders other than hyperpigmentation

A decrease in the cellular and serum levels of glutathione has been speculated to be associated with the pathogenesis of autoimmune and inflammatory dermatoses that include psoriasis, vitiligo, alopecia areata, polymorphic light eruption, acne vulgaris, etc.[43],[44],[45],[46],[47] In addition, there is sufficient evidence demonstrating the importance of glutathione levels in the genesis of melanoma and related skin tumors.[48]

Future developments

Liposomal glutathione consists of the molecule encapsulated in water inside a fat ball with the intention of “tricking” the digestive system to interpret it as a fat cell. This prevents it from being hydrolysed thereby allowing it to enter the bloodstream. However, the lack of human trials, quick degradability of liposomes and safety concerns of soy lecithin (a liposomal component) are barriers against its current use.

S-acetyl-glutathione consists of oral glutathione attached to a sulfur atom. It is taken up intact by chylomicrons in the gut. The acetyl group prevents its oxidation and increases its plasma stability. Studies conducted in mice and human foreskin fibroblasts have revealed that S-acetyl-glutathione molecules are taken up directly by cells with subsequent conversion to glutathione by cleavage of the acetyl bond within the cell. This results in higher levels of intracellular glutathione.[49] S-acetyl-glutathione is also known to have antiviral and immunomodulatory properties.[50] However, there is no human data available to prove the superiority of S-acetyl-glutathione over plain glutathione for skin-lightening effects.

Conclusion

As of now, there is a lack of robust evidence in favour of glutathione for the treatment of hyperpigmentation. The mechanism of action favours its potential as a skin lightening agent. Only three randomized controlled trials have been conducted so far but with short term follow-up periods. These studies support some skin lightening effects of topical, as well as oral glutathione. The safety profile of topical and oral glutathione seems to be reasonable. The use of intravenous glutathione finds no evidence to support it and is further marred by its potential complications. The need of the hour is to have more randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials with a larger sample size, long term follow-up period, with well defined primary and secondary outcomes, targeted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of the skin-lightening effects of topical, oral and parenteral glutathione. In addition, the role of glutathione in specific disorders of hyperpigmentation needs to be elucidated.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Dickinson DA, Forman HJ. Glutathione in defense and signaling: Lessons from a small thiol. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2002;973:488-504.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Murray RK. Metabolism of xenobiotics. In: Murray RK, Bender DA, Botham KM, Kennelly PJ, Rodwell VW, Weil PA, editors. Harper's Illustrated Biochemistry. 28th ed. Michigan: McGraw-Hill; 2009. p. 612-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Exner R, Wessner B, Manhart N, Roth E. Therapeutic potential of glutathione. Wien Klin Wochenschr 2000;112:610-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Meister A, Tate SS. Glutathione and related gamma-glutamyl compounds: Biosynthesis and utilization. Annu Rev Biochem 1976;45:559-604.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Townsend DM, Tew KD, Tapiero H. The importance of glutathione in human disease. Biomed Pharmacother 2003;57:145-55.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Herzenberg LA, De Rosa SC, Dubs JG, Roederer M, Anderson MT, Ela SW, et al. Glutathione deficiency is associated with impaired survival in HIV disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997;94:1967-72.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Kern JK, Geier DA, Adams JB, Garver CR, Audhya T, Geier MR. A clinical trial of glutathione supplementation in autism spectrum disorders. Med Sci Monit 2011;17:CR677-82.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Grey V, Mohammed SR, Smountas AA, Bahlool R, Lands LC. Improved glutathione status in young adult patients with cystic fibrosis supplemented with whey protein. J Cyst Fibros 2003;2:195-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Nordlund JJ, Boissy RE. The biology of melanocytes. In: Freinkel RK, Woodley DT, editors. The Biology of the Skin. New York: CRC Press; 2001. p. 113-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Watanabe F, Hashizume E, Chan GP, Kamimura A. Skin-lightening and skin-condition-improving effects of topical oxidized glutathione: A double-blind and placebo-controlled clinical trial in healthy women. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol 2014;7:267-74.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Masaki H. Role of antioxidants in the skin: Anti-aging effects. J Dermatol Sci 2010;58:85-90.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Halprin KM, Ohkawara A. Glutathione and human pigmentation. Arch Dermatol 1966;94:355-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Yamamura T, Onishi J, Nishiyama T. Antimelanogenic activity of hydrocoumarins in cultured normal human melanocytes by stimulating intracellular glutathione synthesis. Arch Dermatol Res 2002;294:349-54.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Karg E, Odh G, Wittbjer A, Rosengren E, Rorsman H. Hydrogen peroxide as an inducer of elevated tyrosinase level in melanoma cells. J Invest Dermatol 1993;100 2 Suppl:209S-13S.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Maeda K, Hatao M. Involvement of photooxidation of melanogenic precursors in prolonged pigmentation induced by ultraviolet A. J Invest Dermatol 2004;122:503-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Seçkin HY, Kalkan G, Bas Y, Akbas A, Önder Y, Özyurt H, et al. Oxidative stress status in patients with melasma. Cutan Ocul Toxicol 2014;33:212-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Villarama CD, Maibach HI. Glutathione as a depigmenting agent: An overview. Int J Cosmet Sci 2005;27:147-53.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Available from: . [Last accessed on 2015 Apr 17].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

The Perfect Peel. Available from: https://www.medicadepot.com/the-perfect-peel-online.html. [Last accessed on 2015 Mar 26].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Glutathione and Mesotherapy. Available from: http://www.treato.com/Glutathione, Mesotherapy/?a=s. [Last accessed on 2015 Apr 17].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Hagen TM, Wierzbicka GT, Bowman BB, Aw TY, Jones DP. Fate of dietary glutathione: Disposition in the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Physiol 1990;259(4 Pt 1):G530-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Hagen TM, Wierzbicka GT, Sillau AH, Bowman BB, Jones DP. Bioavailability of dietary glutathione: Effect on plasma concentration. Am J Physiol 1990;259(4 Pt 1):G524-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Whillier S, Raftos JE, Chapman B, Kuchel PW. Role of N-acetylcysteine and cystine in glutathione synthesis in human erythrocytes. Redox Rep 2009;14:115-24.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Witschi A, Reddy S, Stofer B, Lauterburg BH. The systemic availability of oral glutathione. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 1992;43:667-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Hagen TM, Jones DP. Role of glutathione in extrahepatic detoxification. In: Sakamoto Y, Higashi T, Taniguchi N, Meister A, editors. Glutathione Centennial: Molecular and Clinical Implications. New York Academic Press; 1989. p. 423-33.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Allen J, Bradley RD. Effects of oral glutathione supplementation on systemic oxidative stress biomarkers in human volunteers. J Altern Complement Med. 2011;17(9):827-33.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Richie JP Jr., Nichenametla S, Neidig W, Calcagnotto A, Haley JS, Schell TD, et al. Randomized controlled trial of oral glutathione supplementation on body stores of glutathione. Eur J Nutr 2015;54:251-63.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Park EY, Shimura N, Konishi T, Sauchi Y, Wada S, Aoi W, et al. Increase in the protein-bound form of glutathione in human blood after the oral administration of glutathione. J Agric Food Chem 2014;62:6183-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 29. |

Demopoulos HB, Ross J. Methods of Manufacturing High Dosage Glutathione, the Tablets and Capsules Produced Thereby; 1993. Available from: http://www.google.com/patents/WO1993019740A1?cl=en. [Last accessed on 2015 Mar 26].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 30. |

Jariwalla RJ, Lalezari J, Cenko D, Mansour SE, Kumar A, Gangapurkar B, et al. Restoration of blood total glutathione status and lymphocyte function following alpha-lipoic acid supplementation in patients with HIV infection. J Altern Complement Med 2008;14:139-46.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 31. |

Glutathione Skin Lightening Pills in India. Available from: http://www.bangalore.click.in/glutathione-skin-lightening-pills-in-india-c75-v4148389. [Last accessed on 2015 Mar 26].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 32. |

GRAS Notice for Glutathione; 2009. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/ucm/groups/fdagov-public/@fdagov-foods-gen/documents/document/ucm269318.pdf. [Last accessed on 2015 Mar 26].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 33. |

Arjinpathana N, Asawanonda P. Glutathione as an oral lightening agent: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Dermatolog Treat 2012;23:97-102.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 34. |

Handog EB, Datuin MS, Singzon IA. An open-label, single-arm trial of the safety and efficacy of a novel preparation of glutathione as a skin-lightening agent in Filipino women. Int J Dermatol 2016;55:153-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 35. |

Suzuki H, Miki S, Oshima M, Sado T. Chronic toxicity and teratogenicity studies of glutathione sodium salt. Clin Rep 1972;6:2393.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 36. |

Lenzi A, Lombardo F, Gandini L, Culasso F, Dondero F. Glutathione therapy for male infertility. Arch Androl 1992;29:65-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 37. |

Paolisso G, Giugliano D, Pizza G, Gambardella A, Tesauro P, Varricchio M, et al. Glutathione infusion potentiates glucose-induced insulin secretion in aged patients with impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care 1992;15:1-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 38. |

Lazo SH. Safety on the Off-label Use of Glutathione Solution for Injection (IV). Food and Drug Administration, Department of Health, Republic of the Philippines; 2011. http://www.fda.gov.ph/attachments/article/38960/Advisories_cosmetic_DOH-FDA%20Advisory%20No.%202011-004.pdf [last accessed on 2016 Feb 18].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 39. |

Mercola D, Hofmekler O. Glutathione: This One Antioxidant Keeps All Other Antioxidants Performing at Peak Levels. Available from: http://www.articles.mercola.com/sites/articles/archive/2010/04/10/can-you-use-food-to-increase-glutathione-instead-of-supplements.aspx. [Last accessed on 2015 Mar 26].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 40. |

Pressman AH, Buff S, editors. Glutathione: The Ultimate Antioxidant. 1st ed. New York: St. Martin's Paperbacks; 1998.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 41. |

Alexis AF, Blackcloud P. Natural ingredients for darker skin types: Growing options for hyperpigmentation. J Drugs Dermatol 2013;12 9 Suppl: s123-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 42. |

Perricone NV. Skin Hyperpigmentation Acyl Glutathione Treatments. Patent US 20110250157 A1; October 13, 2011. Available from: http://www.google.com/patents/US20110250157. [Last accessed on 2015 Apr 17].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 43. |

Prussick R, Prussick L, Gutman J. Psoriasis improvement in patients using glutathione-enhancing, nondenatured whey protein isolate: A pilot study. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 2013;6:23-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 44. |

Shin JW, Nam KM, Choi HR, Huh SY, Kim SW, Youn SW, et al. Erythrocyte malondialdehyde and glutathione levels in vitiligo patients. Ann Dermatol 2010;22:279-83.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 45. |

Yenin JZ, Serarslan G, Yönden Z, Ulutas KT. Investigation of oxidative stress in patients with alopecia areata and its relationship with disease severity, duration, recurrence and pattern. Clin Exp Dermatol 2015;40:617-21.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 46. |

Millard TP, Fryer AA, McGregor JM. A protective effect of glutathione-S-transferase GSTP1*Val(105) against polymorphic light eruption. J Invest Dermatol 2008;128:1901-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 47. |

Ikeno H, Tochio T, Tanaka H, Nakata S. Decrease in glutathione may be involved in pathogenesis of acne vulgaris. J Cosmet Dermatol 2011;10:240-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 48. |

Panich U, Onkoksoong T, Limsaengurai S, Akarasereenont P, Wongkajornsilp A. UVA-induced melanogenesis and modulation of glutathione redox system in different melanoma cell lines: The protective effect of gallic acid. J Photochem Photobiol B 2012;108:16-22.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 49. |

Vogel JU, Cinatl J, Dauletbaev N, Buxbaum S, Treusch G, Cinatl J Jr., et al. Effects of S-acetylglutathione in cell and animal model of herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. Med Microbiol Immunol 2005;194:55-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 50. |

Fraternale A, Paoletti MF, Casabianca A, Oiry J, Clayette P, Vogel JU, et al. Antiviral and immunomodulatory properties of new pro-glutathione (GSH) molecules. Curr Med Chem 2006;13:1749-55.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

236,014

PDF downloads

18,416