Translate this page into:

Group discussion: Prepare, learn, teach and assess

Correspondence Address:

Garehatty Rudrappa Kanthraj

"Sri Mallikarjuna Nilaya", # Hig 33 Group 1 Phase 2, Hootagally KHB Extension, Mysore - 570 018, Karnataka

India

| How to cite this article: Kanthraj GR. Group discussion: Prepare, learn, teach and assess. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2007;73:442-444 |

In recent times, medical education has witnessed developments and modifications in both teaching and assessing curriculum. They include journal clubs to structured journal clubss, seminars to group discussions and case presentations to mini-case evaluation exercises. These academic exercises aim to achieve competency among residents. Recently, structured journal clubs and group discussions have emerged as parts of both teaching and assessing curriculum.

Teaching and learning are based on synchronous, constructive and constant interactions between the residents and the faculty to develop competency. George Miller′s pyramid, [1] which assesses competency involves the following sequential steps:

- Knows of

- Knows how

- Shows how and

- Does

Steps such as ′Knows of′ and ′does′ are the lowest and the highest ends of the spectrum, respectively. Recently, ′heard of ′ [2] has also been incorporated into the pyramid. In stage 1 (heard of), the given topic has come to the resident′s notice through someone, for example, the resident may have heard of the matter in a seminar or a conference presentation. In stage 2 (knows of), the residents have read the subject. In stage 3 (knows how), apart from reading, the residents have systematically analyzed the subject while in stages 4 (shows how) and 5 (does), they have also put it into practice.

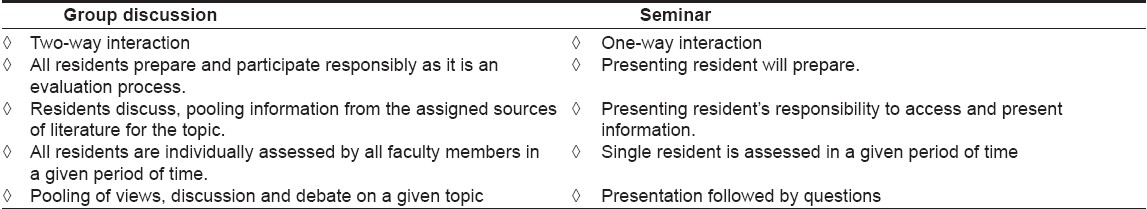

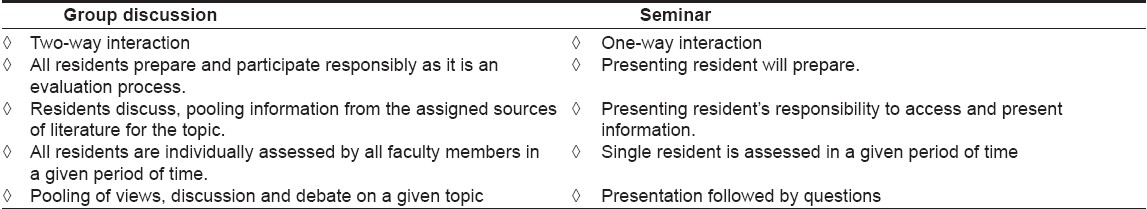

Burge [3] has cautioned that residents could adopt a superficial approach if they are overloaded with curricula. Teaching centers can use a range of assessment techniques for testing curricular outcomes. Seminars, case presentations and journal clubs [4] are various forums of a residency-teaching program, which usually cover the core topics. However, there are certain topics which are often difficult to understand and require maximum mutual interaction to ease learning and reinforce the knowledge. Group discussion (GD) is one such academic exercise that involves a two-way, mutual interaction on a selected topic. In this article, the author presents GD, a resident teaching and assessment curriculum. The toughest chapters in a specialty can be learned in a user-friendly manner by sharing each other′s views. The faculty closely monitors the performance of the whole group of residents in a given time, unlike seminars and case presentations, where only a single resident is assessed. Recently, structured journal clubs [5] and group discussions have emerged as both teaching and assessment curricula. The differences between GDs and seminars are summarized in [Table - 1].

The Objectives of GD

Poor performance in certain theoretical topics even by the above-average residents in monthly, internal assessments stimulated the faculty to design an alternative curriculum to deal with very challenging dermatology chapters. Residents were asked to pool topics which they found to be difficult. Consequently, GD evolved as a forum to deal with difficult topics.

What are Difficult Topics in Dermatology ?

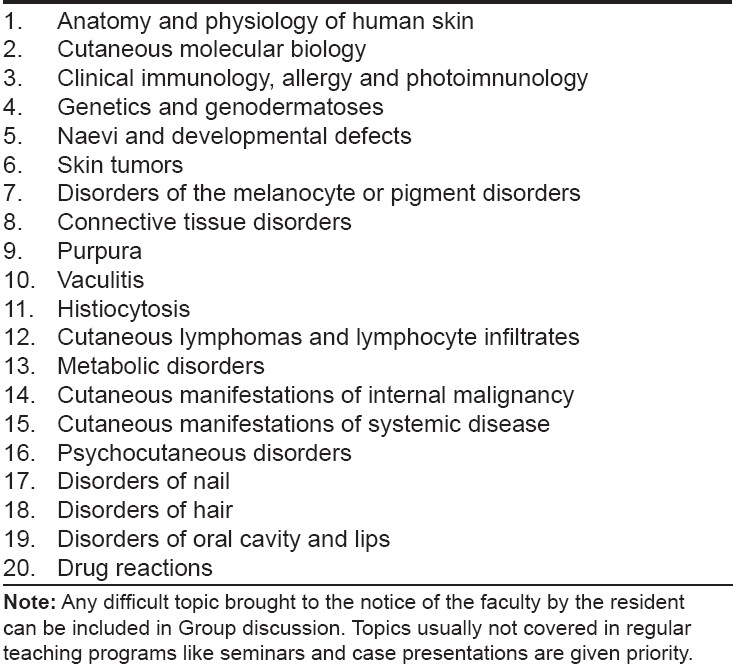

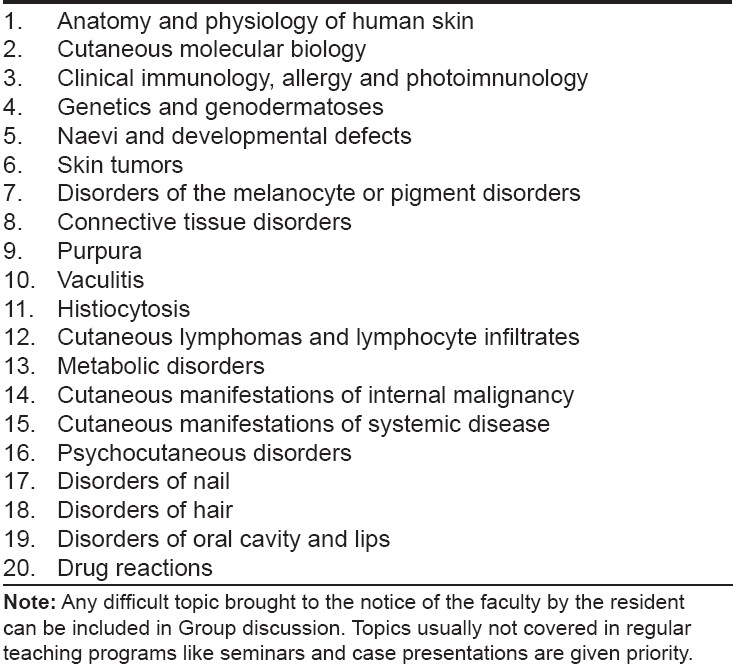

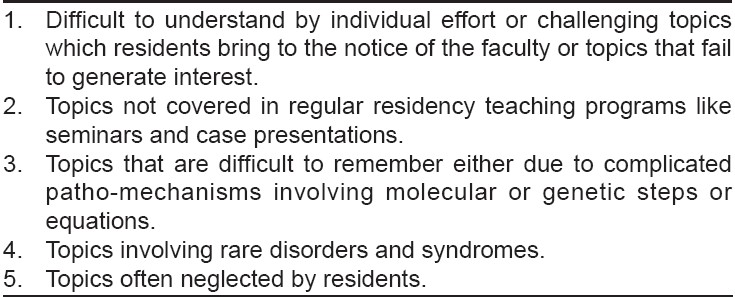

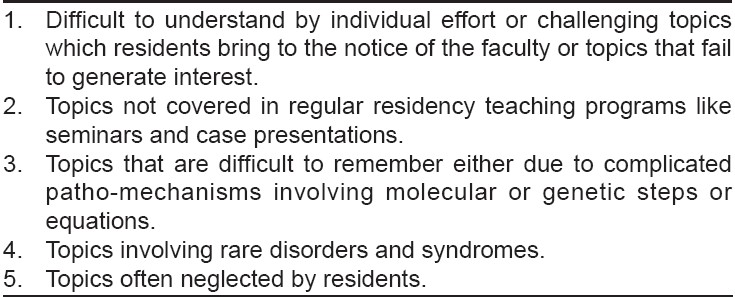

Criteria for including topics for group discussion are summarized in [Table - 2]. Difficult topics actually included for GD are summarized in [Table - 3]. These topics can be given special emphasis in this session.

Design of the GD Curriculum

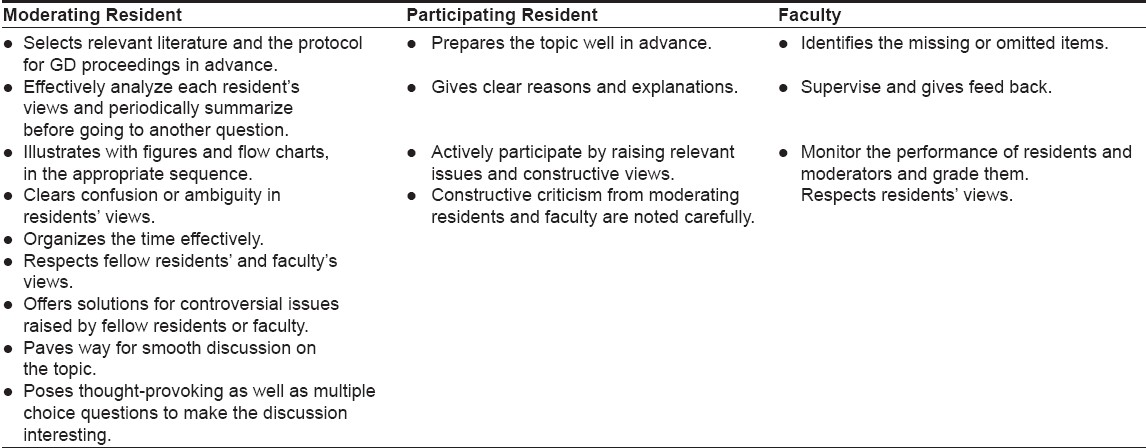

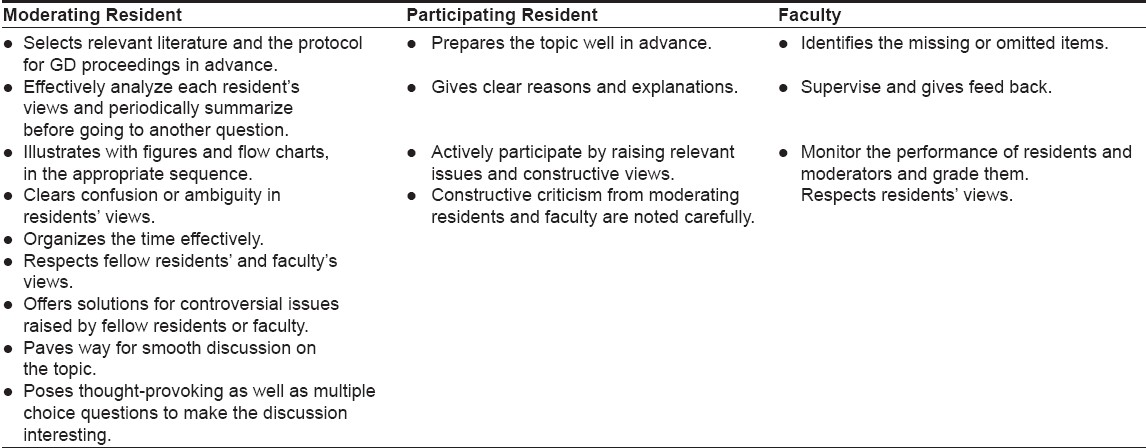

Properly planned groundwork is essential for the success of GD. Two moderators, preferable one senior and one junior postgraduate are entrusted to facilitate GD. The junior moderator acquires the necessary guidance from the senior one in conducting the session. Under the close supervision of faculty who allot the topics for GD, moderators and the participating residents collectively work for the success of the GD. The ideal characteristics of moderating residents, participating residents and faculty for a GD are summarized in [Table - 4].

Role of moderators

Step 1: Moderators search relevant literature for information on the topic either from the library or from internet surveys. They then recommend the most useful textbooks or continuing medical education (CME) or review articles to other residents before interacting with them regarding the GD topic. The faculty gives the necessary guidance in this matter.

Step 2: Moderators prepare relevant flow charts or diagrams or mnemonics (to remember signs and syndromes) or any illustrative material to make the topic easy and interesting. They even prepare relevant, multiple-choice questions to reinforce the important and difficult points to remember and present at appropriate points in the GD.

Step 3: Moderators systematically prepare the list of questions to be discussed in the GD session.

Role of residents

Having been given the topic and the necessary sources of information well in advance of the GD, they prepare themselves in parallel to the moderators. A good resident should be able to search the relevant literature and contribute equally along with the moderators. GD is thus a forum to assess responsibility, preparation and participation of residents.

The GD Session

In each GD session, moderators welcome the faculty and residents, introduce the given topic and highlight its significance. With this background, they begin the discussion by putting questions to their fellow residents. Systematically, each resident′s opinion is aired for every question ensuring participation for all residents. Moderators strictly discourage their fellow residents from stating ′No opinion ′or simply the words ′Same opinion′ to answers by a previous colleague without attempting to answer. Moderators however, strictly adhere to the set timelines and ensure smooth proceedings.

For each question, moderators observe answers, omissions and additional contributions of their colleagues. They note these points and summarize before proceeding to the next question. They periodically display flow charts or illustrative items prepared by them, at appropriate points in the GD. They introduce multiple-choice questions prepared by them to generate interest or drive home the message on an easily forgettable point. Moderators observe their colleagues not only for correct answers but also systematic analysis as to the why, what and how. For each multiple choice question, residents have to defend their choice logically. Apart from answering or giving additional information, residents are encouraged to counter-question the moderators and their fellow residents regarding any lacunae and they can constructively challenge the answers for a given question. Thus, GD is a mutual interaction between the residents and the moderators.

Role of the Faculty

The faculty observes and keeps a track of the interaction between the residents and the moderators, observing, intervening and offering constructive suggestions. The faculty closely monitors the performance of all residents in a given period of time and must resolve any controversies arising from discussions on a particular question. Hence, GD serves as an effective alternative to internal assessments of theoretical knowledge. Thus, systematically organized and periodic GDs in a department can both teach and assess residents on difficult topics.

A teaching program should have definite learning outcomes. Burge [3] has highlighted the learning outcomes for a teaching curriculum. In GDs, all residents prepare, learn, teach and assess information to be able to participate, consequently, it motivates them to develop self-motivated learning skills and promotes deeper understanding of the subject. GD enhances learning challenging or often neglected dermatology topics, making these parts of an interesting and friendly teaching exercise. GD is an active learning program for both residents and faculty.

| 1. |

Miller GE. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Acad Med 1990;65:863-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Peile ED. Knowing and knowing about. BMJ 2006;332:645.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Burge SM. Curriculum planning in dermatology. Clin Exp Dermatol 2004;29:100-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Kanthraj GR Srinivas CR. Journal club: screen, select, probe and evaluate. Indian J dermatol Venered Leprol 2005;75:435-40.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Hatala R, Keitz SA, Wilson MC, Guya HG. Beyond journal clubs. Moving toward an integrated evidence-based medicine curriculum. J Gen Intern Med 2006;20:538-41.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

4,374

PDF downloads

3,979