Translate this page into:

Infantile onset of Cockayne syndrome in two siblings

Correspondence Address:

Prerna Batra

Type II, Quarter No 1, MGIMS Campus, Sevagram, Wardha, Maharashtra - 442102

India

| How to cite this article: Batra P, Saha A, Kumar A. Infantile onset of Cockayne syndrome in two siblings. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:65-67 |

|

| Figure 1: Characteristic facies of Cockayne syndrome in Case 1 |

|

| Figure 1: Characteristic facies of Cockayne syndrome in Case 1 |

Sir,

Cockayne syndrome is a rare autosomal recessive degenerative disease with cutaneous, ocular, neurologic and somatic abnormalities. The entity was first described in 1936 by Cockayne. Till now around 150 cases have been reported in the literature. [1] Classically, Cockayne syndrome has onset in the second year of life, however, rarely, cases with early neonatal onset and death in infancy have also been reported. We report two siblings of this syndrome with onset in early infancy. Differential diagnosis of the syndrome and need for molecular diagnostic tests is emphasized to identify the various mutations associated with this condition.

Our first case was a 7-year-old male child who presented with history of appearance of rashes, specifically in the malar area on exposure to sunlight followed by peeling of skin since the age of 4 months and delayed development. The child was born of a non-consanguineous marriage, third in order in the family of seven siblings. Diagnosis of photosensitivity was made in infancy by a practicing dermatologist as evident by earlier medical records. Examination revealed a proportionately short-statured child having both weight and height lying below the third percentile for age, extreme cachexia, microcephaly, senile look, loss of subcutaneous fat, pinched nose giving a characteristic ′Mickey mouse′ appearance to the child [Figure - 1]. The patient had hyperpigmented yellowish brown macules over the malar area with scars, large ears, dental caries, long hands and feet with swollen knees and interphalangeal joints. Central nervous system examination showed low IQ with normal motor and sensory examination. Fundus examination showed bilateral optic atrophy with retinal degeneration. Audiometry revealed bilateral conductive hearing loss. Rest of the systemic examination was within normal limits. Blood counts, renal function tests, liver function tests, serum electrolytes, calcium and phosphate levels were normal. His bone age corresponded with the chronological age. Cranial CT revealed bilateral basal ganglia calcifications with mild diffuse brain atrophy. Nerve conduction velocity showed slow motor conduction suggestive of demyelination. His electroencephalogram was normal.

Our second case was a 6-month-old sister of Case 1, sixth in birth order, who presented with appearance of erythematous rashes over the malar area of the face since the past 2 months. She was a full-term baby with normal development at first presentation. Both the babies were in follow-up for 1 year. The elder sibling deteriorated and was confined to a wheelchair. The younger sibling had failure to thrive and was not able to sit without support till one and a half years. Her head circumference at this age was 40 cm. Audiometry revealed impaired hearing, though fundus was normal. Parents refused any further investigation for the younger sibling. A diagnosis of Cockayne syndrome was made in both the siblings.

Cockayne syndrome (CS) is an inherited syndrome characterized by short stature, mental deficiency, photosensitivity, disproportionately large hands, feet and ears, ocular defects and extensive demyelination. This rare disorder affects both sexes equally, inherited by autosomal recessive mode. Skin fibroblasts show defective growth in tissue culture and are abnormally sensitive to UV radiation. Unlike xeroderma pigmentosum, nucleotide excision repair process is normal in Cockayne syndrome cells, rather a sub pathway of nucleotide excision repair process i.e. preferential rapid transcription coupled repair is defective. Child usually appears normal in the first year of life, although onset in the early neonatal period with early deaths has been reported. [2],[3],[4],[5] Survival beyond the second decade is unusual, though patients have been reported to survive till the fourth decade.

Nance and Berry have distinguished three clinically different classes of the disease. [6] A classical form (CS I) which includes the majority of patients, a severe form (CS II) characterized by early onset and severe progression of manifestations and a mild form, typified by late onset and slow progression of disease. Classical CS patients show (1) growth failure, (2) neurodevelopmental and neurological dysfunction, (3) cutaneous photosensitivity, (4) progressive ocular abnormalities (pigmentary retinopathy, cataract), (5) hearing loss, (6) dental caries, (7) characteristic wizened facial appearance: bird-like facies. For diagnosis of CS in an infant, the presence of the first two criteria and a few of the other five criteria are required. The last four features are usually seen in older patients. Physical and mental development is greatly retarded, though sexual maturation may occur in some. Skeletal deformities and limited joint movements increase the child′s disabilities. The CT scan shows basal ganglia calcifications.

The elder sibling of our cases had all the features of the syndrome that developed at an early age and the younger sibling also had evolving lesions. Hence both siblings had features similar to CS II. The onset was in infancy with characteristic facial and somatic appearance within 2 years of life. The prognosis in this type is much worse than the classical CS patients, as seen in our cases.

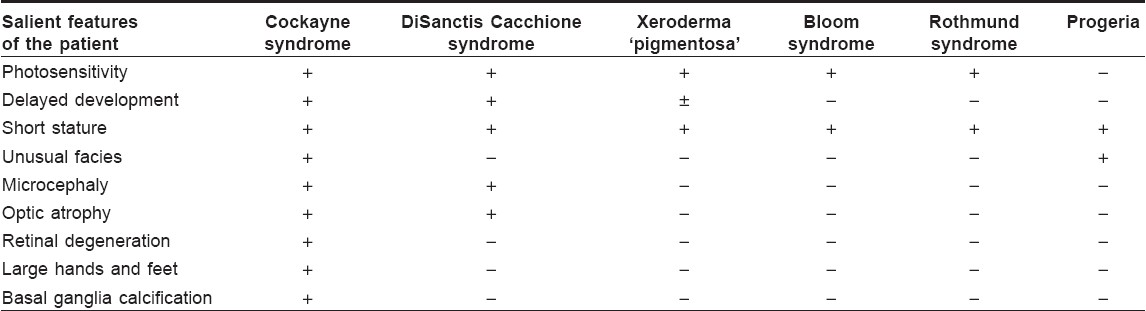

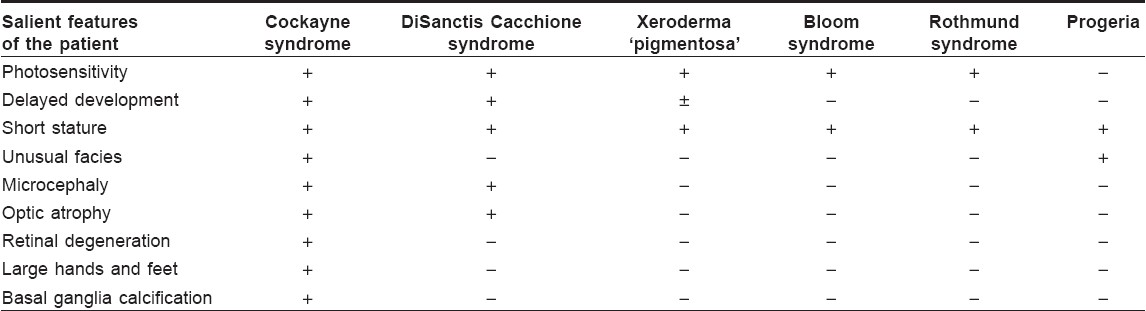

Cockayne syndrome has to be differentiated from other conditions having similar clinical features. [Table - 1] highlights the conditions to be considered and their differentiating features.

Diagnosis of the condition is made by characteristic clinical features specific to this, but the definitive diagnosis is achieved by laboratory investigations such as cytogenetic, biochemical and molecular methods. By carrying out complementation tests on CS cells, five complementation groups have been identified, out of which two, CS-A and CS-B are responsible for more than 90% of the cases. [7] It has been observed that mutations in the ERCC6 gene are responsible for most common forms of the disease. [8]

There is no cure for the disease. Management is targeted towards associated problems. Patients must be protected from sunlight by every possible means. Physiotherapy should be advised to avoid contractures and counseling should be done to prevent recurrence of the condition in the family.

Prenatal diagnosis is now possible for the condition by fast growing chorionic villous cultures and amniotic fluid cell cultures. However, the cytogenetic methods used conventionally are time-consuming and labor-intensive and always carry a risk of culture failure or contamination by bacteria ′or′ fungal growth. [8] There is a need to develop molecular techniques in India for quick and reliable diagnosis of such conditions.

| 1. |

Ozdirim E, Topcu M, Ozon A, Cila A. Cockayne syndrome: Review of 25 cases. Pediatr Neurol 1996;15:312-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Jaeken J, Klocker H, Schwaiger H, Bellmann R, Hirsch-Kauffmann M, Schweiger M. Clinical and biochemical studies in three patients with severe early infantile Cockayne syndrome. Hum Genet 1989;83:339-46.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Goto K, Ogawa T. A case of Cockayne syndrome with clinical syndrome in the neonatal period. No To Hattatsu 1989;21:491-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Okamoto N, Otani K, Futagi Y, Nishida M. Cockayne syndrome: Sibling with different ultraviolet sensitivity and early onset of manifestations. No To Hattatsu 1989;21:265-70.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Patton MA, Giannelli F, Francis AJ, Baraitser M, Harding B, Williams AJ. Early on set Cockayne syndrome: Case report with neuropathological and fibroblast studies. J Med Genet 1989;26:154-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Nance MA, Berry SA. Cockayne syndrome: Review of 140 cases. Am J Med Genet 1992;42:68-84.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Stefanini M, Fawcwtt H, Botta E, Nardo T, Lehmann AR. Genetic analysis of twenty two patients with Cockayne Syndrome. Hum Genet 1996;97:418-23.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Troelstra C, Hesen W, Bootsma, Hoeijmakers JH. Structure and expression of the excision repair gene ERCC 6 involved in the human disorder Cockayne syndrome group B. Nucleic Acids Res 1993;21:419-26.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

3,873

PDF downloads

3,361