Translate this page into:

Leukocytoclastic vasculitis during pegylated interferon and ribavirin treatment of hepatitis C virus infection

2 Department of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases, Gazi University, Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey

Correspondence Address:

Esra Adisen

Department of Dermatology, Gazi University, Faculty of Medicine, Besevler, 06500 Ankara

Turkey

| How to cite this article: Adisen E, Dizbay M, Hizel K, Ilter N. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis during pegylated interferon and ribavirin treatment of hepatitis C virus infection. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:60-62 |

|

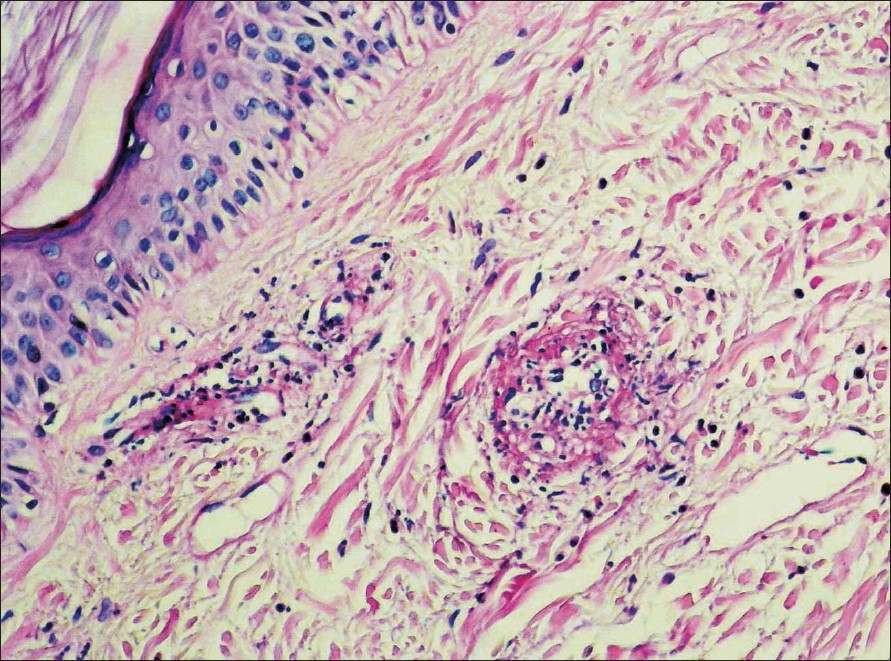

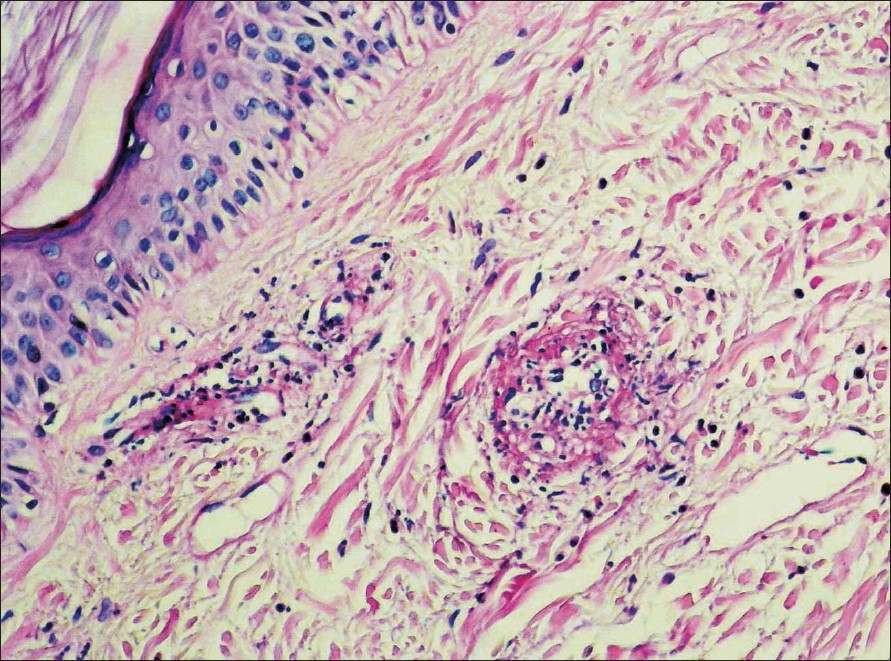

| Figure 1: Predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate affecting papillary dermal vessel walls, leukocytoclasia and deposition of fibrin (H and E, X200) |

|

| Figure 1: Predominantly neutrophilic infiltrate affecting papillary dermal vessel walls, leukocytoclasia and deposition of fibrin (H and E, X200) |

Sir,

Chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection is one of the main causes of liver disease in the world. Based on several clinical trials, pegylated interferon (peg-IFN) plus ribavirin (RIB) given for 24 or 48 weeks is now established as the standard therapy in chronic HCV infection. [1] However, side-effects are common and sometimes serious, leading to discontinuation of treatment. Compared with IFN alone, peg-IFN/RIB combination treatment is associated with a higher incidence of cutaneous side-effects. [1] Herein we report a woman who developed leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LCV) during peg-IFN and RIB treatment of HCV infection. To our knowledge, new onset LCV in HCV patients taking this combination has not been described so far.

A 57-year-old woman was diagnosed of chronic HCV infection in March 2005 with a HCV viral load of 4 x 10 5 copy/ml. Genotyping was not performed due to financial constraints. Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) was 53 U/L (Normal < 40 U/L) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) was 66 U/L (Normal < 40 U/L). The rest of the biochemistry panel and hematological counts were in normal limits. Serum assay for cryoglobulins and autoimmune markers (antinuclear antigens, antimitochondrial antigen, anti-liver kidney microsomal antibodies, anti-smooth muscle antibodies) was negative. Thyroid function tests were normal. Liver ultrasonography showed minimal hepatomegaly with Grade I steatosis. Patient had a Knodell histology activity index score of 10. The patient had not been treated with any type of IFN. Combination therapy with peg-IFN 2a (180 mcg wk) and RIB (1000 mg/d) for 48 weeks was initiated. Three months later, HCV-RNA was undetectable in the serum and liver function tests returned to normal values. However, absolute neutrophil count was found to decrease to 1000/mm 3 and peg-IFN 2a dose was reduced to 135 mcg/wk while RIB was continued with the initial dose. In the sixth month of the therapy, absolute neutrophil count was found to decrease to 750/mm 3 , even after the reduction of peg-IFN 2a to 135 mcg/wk. Because adjustment of the size of peg-IFN 2b dose is easier, it was decided to give peg-IFN 2b with a low dose (0.75 mcg/kg/wk) with close monitoring of neutrophil count. One month later, the patient noticed painful skin lesions four days after the last injection of peg-IFN 2b. She denied using any other medications. On dermatological examination, palpable erythematous plaques were observed on the anterior aspect of her right leg. Histopathological examination of these lesions revealed LCV [Figure - 1]. Hematocrit, leukocyte and platelet counts, AST, ALT, serum protein, urinalysis and serum creatinine levels, thyroid-stimulating hormone, α-1 antitrypsin, α-fetoprotein, ceruloplasmin, the C3 and C4 fractions of complement and rheumatoid factor were either normal or negative. Occult blood was not determined in the stool. In the serum, HCV-RNA was still negative with PCR method. Serological assays for autoimmune markers and serum assay for cryoglobulins were negative. The combination therapy was stopped. The patient was treated with tiaprofenic acid (300 mg/d) and clobetasol 17-propionate ointment. After three weeks, skin symptoms healed with postinflammatory pigmentation. During the follow-up, the patient remained HCV-RNA negative.

In our patient, the chronological link between the occurrence of LCV and the treatment, the resolution of lesions after withdrawal of peg-IFN/RIB, negative PCR results of HCV and the absence of any other detectable cause of LCV forced us to think that this condition represented a side-effect of peg-IFN/RIB combination therapy. This potential relationship deserves further attention. At this point, it is important to distinguish the lesions associated with the combination therapy from those associated with the disease itself. The most common form of vasculitis in HCV patients is mixed cryoglobulinemia. [2],[3] Our patient lacked clinical signs of the cryoglobulinemia syndrome and her disease was not in the active stage as shown by a negative PCR. Also, the onset of lesions just after the injection of peg-IFN at a time when virus C was undetectable favored existence of a cause other than HCV infection in the development of LCV. In our opinion, a possible association between LCV and the peg-IFN/RIB treatment should be considered. Though we could not confirm it in the absence of a challenge test, according to current literature, peg-IFN is much more likely to have played a role in our patient′s disease than RIB.

The IFNs may cause new onset or exacerbation of cryoglobulinemic or non-cryoglobulinemic vasculitis in HCV-infected patients. [2] Since peg-IFN has a similar side-effect profile when compared with standard IFNs, peg-IFN may also have the capacity to induce vasculitis. Case reports showing exacerbation of HCV-associated cryoglobulinemic vasculitis during peg-IFN therapy support this possibility. [4] Therefore, peg-IFN might have been involved in the development of LCV in our patient. To our knowledge, there are no previous reports on the onset of non-cryoglobulinemic vasculitis or LCV during peg-IFN/RIB therapy of HCV infection.

While recent data encourages using peg-IFN/RIB combination in new indications such as treatment of HCV-related systemic vasculitis, [5] the reasons or the mechanisms of initiation or exacerbation of vasculitis in HCV patients receiving this combination treatment need to be clarified.

| 1. |

Marrache F, Consigny Y, Ripault MP, Cazals-Hatem D, Martinot M, Boyer N, et al . Safety and efficacy of peginterferon plus ribavirin in patients with chronic hepatitis C and bridging fibrosis or cirrhosis. J Viral Hepat 2005;12:421-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Beuthien W, Mellinghoff HU, Kempis J. Vasculitic complications of interferon-alpha treatment for chronic hepatitis C virus infection: Case report and review of the literature. Clin Rheumatol 2005;24:507-15.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Daoud MS, el-Azhary RA, Gibson LE, Lutz ME, Daoud S. Chronic hepatitis C, cryoglobulinemia and cutaneous necrotizing vasculitis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;34:219-23.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Batisse D, Karmochkine M, Jacquot C, Kazatchkine MD, Weiss L. Sustained exacerbation of cryoglobulinemia related vasculitis following treatment of hepatitis C with peginterferon alfa. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2004;16:701-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Cacoub P, Saadoun D, Limal N, Sene D, Lidove O, Piette JC. Pegylated interferon alfa-2b and ribavirin treatment in patients with hepatitis C virus-related systemic vasculitis. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:911-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

2,825

PDF downloads

2,837