Translate this page into:

Major precipitating factors for stigma among stigmatized vitiligo and psoriasis patients with brown-black skin shades

2 Department of Dermatology, Institute of Medical Sciences and SUM Hospital, Bhubaneswar, Odhisha, India

3 Hand Unit, Hamad Medical Corporation, Doha, Qatar

4 Department of Biostatistics, Schieffelin Institute of Health-Research and Leprosy Centre, Karigiri, Vellore, Tamil Nadu, India

Correspondence Address:

Ramaswamy Premkumar

4, Vallalar Street, Thiru Nagar, Gandhi Nagar Township (West), Vellore - 632 006

India

| How to cite this article: Premkumar R, Kar B, Rajan P, Richard J. Major precipitating factors for stigma among stigmatized vitiligo and psoriasis patients with brown-black skin shades. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2013;79:703-705 |

Sir,

Numerous earlier studies had presented the correlation between clinical and demographic parameters and stigmatization; however, their samples were (i) always either on total vitiligo or psoriasis population and were (ii) mostly from light skinned Western-Caucasian cultural backgrounds.

This letter is a part of a larger project that looked into the stigma among psoriasis and vitiligo. [1] Our earlier study [2] was a cross sectional comparative study conducted at Karigiri, South India with a sample of 150 cases each of psoriasis and the same number of vitiligo, a total of 300 subjects. [2] Nearly all of their unexposed skin shades were brown-black and fitted into Fitzpatrick skin type VI [3] and from South Indian cultural background. A detailed clinical, socioeconomic and stigma assessment of these two conditions was done. It measured the level of stigma among these patients and quantified the percent of vitiligo and psoriasis patients minimally participated in domestic and social life, which we defined as stigma by using a recently developed tool called Participation Scale (P-Scale). [4] The reason for using P-Scale was because it uses the framework of the International classification of functioning (ICF), Disability and Health to measure domestic and social participation in such stigmatizing diseases whereas Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) which numerous other studies in psoriasis and vitiligo had administered in the past hardly elaborated ICF model theoretically. [2]

Stigma measurement was among vitiligo and psoriasis patients in comparison to a third group enrolled in the study, serving as controls, comprised 150 adults from both sexes who accompanied the cases to the clinic and who had no dermatological and psychiatric morbidities. During the time of data collection no matching among cases or controls was attempted. The conclusion of stigma was based on this comparison with a control group population. Thus, 26 vitligo and 42 psoriasis patients were identified as suffering from stigma.

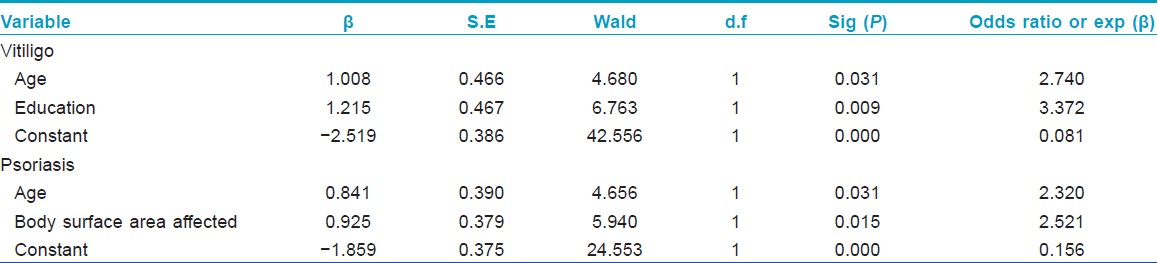

In the second part of the study, only these stigmatized patients were taken for further analysis of each condition individually after adjusting for other covariants using logistic regression.

Careful literature search showed that stigma studies based on brown-black skin shade are unavailable. Such studies will also have an added advantage of extrapolating its findings to other South Indian, African and Aborigine population who share similar skin type. We specifically investigated the clinical and demographic profile of the above patients in order to find out the factors that influenced it.

The results depicted that with age increase (41-year and above), stigma also increases among vitiligo and psoriasis; vitiligo have 2.74 times and psoriasis have 2.32 times higher chances of stigma to those who aged 40 years and below with brown-black skin type. Stigma impact increases by 3.37 times with less education among vitiligo population, whereas in psoriasis, increase in the percentage of body parts affected contributes to add stigma by 2.52 times higher chances. The overall predictive power of its equation for vitiligo and psoriasis was 82.7% and 72%, respectively.

The uniqueness of this study is it focused only on the stigmatized sections of these diseases population to specify the factors which influenced it; as well, it fulfilled the need to investigate this problem from a population with brown-black skin shade. As per Fitzpatrick skin shade classification [3] South Indians, Africans and Aborigines share this color blend. This study also considered the original skin color of vitiligo and psoriasis patients as one among the essential parameters to measure stigma.

In order to systematically analyze different factors that precipitates stigma, firstly univariate analysis was done. It did not show any significance except the body parts affected and that in psoriasis patients alone. Regarding the site of disease in psoriasis, if lesion is present in both exposed and unexposed parts of the body, they had significant stigma compared to the lesions only in the exposed parts of the body [P = 0.008, [Table - 1]. Therefore, logistic regression analysis was undertaken as the next phase. Results of this analysis with this study population showed that both in vitiligo and psoriasis, as their age increases, stigma also increased, whereas a Polish study with predominantly Caucasian population showed that there were no significant relationship between increase in age and stigmatization in psoriasis. [5]

Two explanations we offer for the association between age increase and increase in the intensity of stigma. One is the culture of arranged marriages. It is largely practiced in South Asia and in Africa, to some extent. In an arranged marriage, one of the factors considered in match making is the parents′ health, generally to be without any visible stigmatizing diseases. Individuals with psoriasis and vitiligo may have hard time finding a mate for their children and get married. Second, in India, elders have a major role in community, social and civic life.

Similarly, we found in psoriasis, increase in the percentage of body parts affected contributed to the stigma in their domestic and social lives. A study from North America showed that stigma is not always proportional to or predicted by measure of body surface area involvement. [6] Another three earlier studies from Europe and North America corroborated this finding. [7],[8],[9] Such results clearly bring out that the clinical and demographic parameters that are responsible for stigma differ widely not only between different cultures, but also the skin shades play a major role for this dichotomy. The common perception is that more educated vitiligo individuals are likely to suffer from the stigma, whereas the results showed when education decreased the participation restriction increased. Hence, awareness among Dermatologists treating black skin type population with these health problems about their educational level, age, and body parts involved suffer more from stigma is a message from this study.

At this juncture, we recommend readers to also refer to another important publication on related issue by Porter et al. [10] One important conclusion drawn from this study is that the clinical and demographic factors that influenced stigma among vitiligo and psoriasis population in brown-black skin shade of South Indian culture is by and large different to that of light-skinned Caucasian societal backgrounds.

| 1. |

Premkumar R, Augustine V, Joseph PA, Richard J. Effects of the impact of counseling intervention on life situations in stigmatized vitiligo and psoriasis patients. Study Protocol and Activities Report - unpublished. Karigiri: Funded by the Indian Council of Medical Research; 2011. p. 1-22.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Pichaimuthu R, Ramaswamy P, Bikash K, Joseph R. A measurement of the stigma among vitiligo and psoriasis patients in India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2011;77:300-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Rebate M, Halder RM, Taliaferro SJ. Classification of vitiligo. In: Goldsmith L, editor. Fitzpatrtick's Dermatology in General Medicine. 7 th ed. London: McGraw Hill Medical; 2006. p. 178-80.

th ed. London: McGraw Hill Medical; 2006. p. 178-80.'>[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Participation Scale: Users Manual - Version 6.0. Available from: http://www.ilep.org.uk/documents/participation_scale.[Last cited 2010 Apr 16].

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Hrehorów E, Salomon J, Matusiak L, Reich A, Szepietowski JC. Patients with psoriasis feel stigmatized. Acta Derm Venereol 2011;92:67-72.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Kimball AB, Jacobson C, Weiss S, Vreeland MG, Wu Y. The psychosocial burden of psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2005;6:383-92.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Richards HL, Fortune DG, Griffiths CE, Main CJ. The contribution of perceptions of stigmatisation to disability in patients with psoriasis. J Psychosom Res 2001;50:11-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Finlay AY, Kelly SE. Psoriasis - An index of disability. Clin Exp Dermatol 1987;12:8-11.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Fortune DG, Main CJ, O'Sullivan TM, Griffiths CE. Quality of life in patients with psoriasis: The contribution of clinical variables and psoriasis-specific stress. Br J Dermatol 1997;137:755-84.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Porter JR, Beuf AH. Racial variation in reaction to physical stigma: A study of degree of disturbance by vitiligo among black and white patients. J Health Soc Behav 1991;32:192-204.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

2,936

PDF downloads

1,600