Translate this page into:

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis with marked facial disfigurement

2 Department of Otolaryngology, Medical Faculty of Mustafa Kemal University, Antakya, Hatay, Turkey

3 Department of Parasitology, School of Medicine, Mustafa Kemal University, Antakya, Hatay, Turkey

4 Department of Pathology, School of Medicine, Mustafa Kemal University, Antakya, Hatay, Turkey

Correspondence Address:

Ozlem Ekiz

Department of Dermatology, Tayfur Ata Sokmen Medical School, Mustafa Kemal University, Antakya, Hatay 31000

Turkey

| How to cite this article: Ekiz O, Kahraman &&, Şen BB, Serarslan G, Rifaioğlu EN, Culha G, Özgür T. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis with marked facial disfigurement. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2017;83:91-93 |

Sir,

A 52-year-old Syrian presented to the dermatology department at Hatay Mustafa Kemal University with complaints of facial lesions and purulent rhinitis for 3 months. He also had vitiligo for 20 years. The patient had no history of smoking, alcohol consumption or systemic disease. Dermatologic examination revealed crusted and infiltrated granulomatous plaques on the anterior upper surface and side of the nose, cheeks and lower and upper lips with purulent discharge [Figure - 1]. The lesions had affected the anterior nasal septum and columella. Nasal examination showed mucopus in the nasal cavity, loss of tissue on the columella and cartilage necrosis on the anterior nasal septum and consequently, loss of tip support. In addition, depigmented macules of vitiligo were noted on the face and extremities. General physical examination was normal. Laboratory tests revealed that the white blood cell count was 20.86 × 10[3]/µL (4–10 × 10[3]/µL),

|

| Figure 1: Massively crusted, granulomatous plaques on the central and lower face |

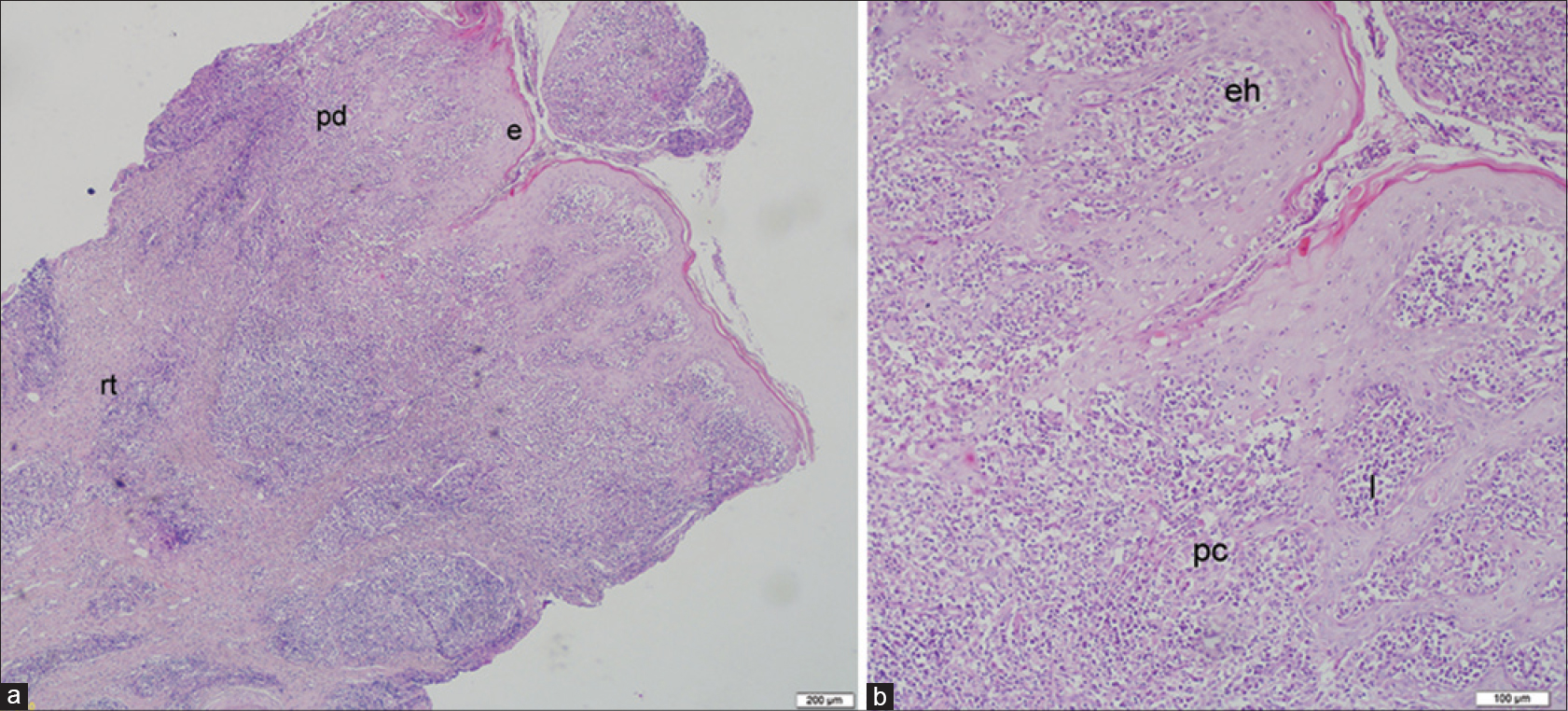

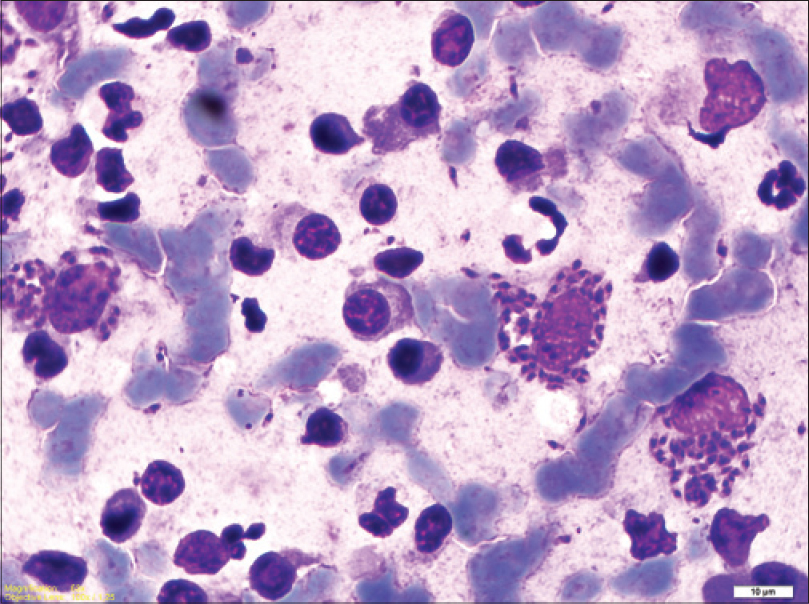

sedimentation rate was 100 mm/h (0–12 mm/h) and C-reactive protein levels were 86.6 mg/dl (0–5 mg/dl). Other laboratory tests were within normal limits. HIV and hepatitis C tests were negative. Culture from the purulent discharge grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa. The patient was treated with levofloxacin, 750 mg by intravenous infusion for 10 days. Following treatment, suppuration decreased and granulomatous lesions became more visible. Histopathologic examination revealed acanthosis with pustule formation on the surface of follicular epithelium and a dense, diffuse inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, many plasma cells and epithelioid cells in the papillary and reticular dermis [Figure - 2]a and [Figure - 2]b. These findings were suggestive of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis but no parasite was seen. Leishmania amastigotes were found in the tissue smear prepared from the edge of the lesion [Figure - 3]. On the basis of history, clinical and histopathological findings and skin smear results, mucocutaneous leishmaniasis was diagnosed. The patient was treated with systemic meglumine antimoniate, 20 mg/kg/day intramuscularly, in 2 divided doses for 30 days. The lesions improved dramatically 1 month after the treatment [Figure - 4].

|

| Figure 2: (a and b) Acanthosis of the epidermis (e), pustule formation on the surface of the follicle, lymphocytes (l), plasma cells (pc) mixed with epithelioid histiocytes (eh) in the papillary (pd) and reticular dermis (rt) (H and E, ×40, ×100) |

|

| Figure 3: Leishmania amastigotes in the tissue smear (Giemsa stain, × 100) |

|

| Figure 4: Significant improvement 1 month after the treatment |

Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis is a serious and potentially life-threatening form of the disease. It is often perceived as a New World disease almost only found in South America but rarely seen in the Old World. Mucosal manifestations can be seen in about 5–20% of cutaneous leishmaniasis. The lag period between developing cutaneous lesions and the later onset of mucosal involvement ranges from months to years. The nasal mucosa is the most commonly affected area and involvement of other mucosal sites is rare.[1] In patients with nasal mucosal involvement, the disease can begin with non-specific symptoms such as persistent nasal stuffiness, discharge, discomfort or epistaxis.[2] Our patient also presented with purulent nasal discharge.

Secondary infection is reported in 54.2% of cases and is usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus.[3] In our case, Pseudomonas aeruginosa was the cause and the patient responded well to treatment with levofloxacin.

Atypical aspects such as extensive and destructive lesions, have often been found in cases of leishmaniasis associated with HIV infection.[4] In our case, although HIV tests were negative, a massive and disfiguring central face involvement occurred in a short time.

The clinching evidence for a diagnosis of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis is the demonstration of Leishmania parasites. On biopsy, amastigotes can be seen in only 25% of the skin lesions.[5] In our case, the histopathological findings were suggestive of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis but amastigotes could not be identified. However, amastigotes were detected by direct microscopic examination.

In mucocutaneous leishmaniasis, long-term systemic treatment with pentavalent antimonials or amphotericin B is required.[5] In view of the extent and severity of the disease, our patient was treated with intramuscular meglumine antimoniate, 20 mg/kg/day for 30 days. Because of the fairly early diagnosis, appropriate treatment and the absence of any underlying primary immunodeficiency, our patient had a good prognosis. In addition, the response to treatment was dramatic.

Early diagnosis and appropriate treatment of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis is essential as there is a risk of extension of the disease and destruction of facial structures such as the nose, palate and buccal mucosa with potentially fatal pharyngeal and laryngeal involvement.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has given his consent for his images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Osorio LE, Castillo CM, Ochoa MT. Mucosal leishmaniasis due to Leishmania (Viannia) panamensis in Colombia: Clinical characteristics. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1998;59:49-52.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Weller PF, Durand ML, Pilch BZ. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 4-2005. A 35-year-old man with nasal congestion, swelling, and pain. N Engl J Med 2005;352:609-15.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Vera LA, Macedo JL, Ciuffo IA, Santos CG, Santos JB. Antimicrobial susceptibility of aerobic bacteria isolated from leishmaniotic ulcers in Corte de Pedra, BA. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 2006;39:47-50.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

da Silva GA, Sugui D, Nunes RF, de Azevedo K, de Azevedo M, Marques A, et al. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis/HIV coinfection presented as a diffuse desquamative rash. Case Rep Infect Dis 2014;2014:293761.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Costa JM, Saldanha AC, Nasciento D, Sampaio G, Carneiro F, Lisboa E, et al. Clınıcal modalıtıes, dıagnosıs and therapeutıc approach of the tegumentary leıshmanıasıs ın Brazıl. Bras Gaz Med Bahia 2009;79 Suppl 3:70-83.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

18,075

PDF downloads

2,533