Translate this page into:

Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome – Simplifying the approach for dermatologists. Part 1: Etiopathogenesis, clinical features and evaluation

Corresponding author: Dr. Pankaj Das, Department of Dermatology, Armed Forces Medical College, Pune, Maharashtra, India. pankaj3609@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Singh GK, Das P, Srivastava S, Singh V, Singh K, Barui S, et al. Mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome – Simplifying the approach for dermatologists. Part 1: Etiopathogenesis, clinical features and evaluation. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2025;91:40-8. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_737_2023

Abstract

Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas (CTCL) are a heterogeneous group of extranodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas characterised by a cutaneous infiltration of malignant monoclonal T lymphocytes. While this broad spectrum of disease with its varied etiopathogenesis, clinical features and management options are well characterised, an approach from a dermatologist’s perspective is lacking in the literature. We strive to elucidate the approach from a clinician’s point of view, especially in respect of clinical examination, investigations, staging and management options that are available in the realm of the dermatologists. This review article is the first part out of the two, covering the etiopathogenesis, clinical features and evaluation.

Keywords

Mycosis fungoides

Sézary syndrome

cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

introduction

etiopathogenesis

clinical examination

Introduction

Cutaneous T-Cell Lymphomas (CTCLs) belong to a heterogeneous group of extranodal non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas which are characterised by infiltration of malignant monoclonal T lymphocytes in the skin. Mycosis Fungoides (MF) restricted to the skin has an indolent progression passing from patch stage to infiltrated plaque and tumour stage. Sézary Syndrome (SS) is defined as an aggressive leukaemic phase type of MF, clinically characterised by erythroderma and generalised lymphadenopathy. MF was first described by Alibert in 1806 as the infiltration of skin by lymphocytes.1 Edelson in 1974 coined the term Cutaneous T-cell lymphomas for MF and its leukaemic variant SS, which are the major types of CTCL.2 They typically affect individuals with a median age of 55–60 years, with an annual incidence of 0.5 per 100,000. MF with its variants and SS constitute a majority of the otherwise wide range of primary cutaneous malignancies classified by the 2018 update of the Cutaneous Lymphoma Task Force of the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer classification (WHO-EORTC) for primary cutaneous lymphomas3 [Table 1]. There are four broad types of CTCL – MF and its variants; CD30 positive lymphoproliferative diseases; SS; and non-MF variants. MF is the most common type of CTCL, representing 44–62% of cases.

| Cutaneous T-cell and NK cell lymphomas |

|---|

| Mycosis fungoides |

| MF variants and subtypes |

| Folliculotropic MF |

| Pagetoid reticulosis |

| Granulomatous slack skin |

| Sézary syndrome |

| Adult T-cell leukaemia/lymphoma |

| Primary cutaneous CD30 + lymphoproliferative disorders |

| Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma |

| Lymphomatoid papulosis |

| Subcutaneous panniculitis-like T-cell lymphoma |

| Extranodal NK/T-cell lymphoma, nasal type |

| Primary cutaneous peripheral T-cell lymphoma, unspecified |

| Primary cutaneous aggressive epidermotropic CD8 + T-cell lymphoma (provisional) |

| Cutaneous γ/δ T-cell lymphoma (provisional) |

| Primary cutaneous CD4 + small-/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma (provisional) |

| Cutaneous B-cell lymphomas |

| Primary cutaneous marginal zone B-cell lymphoma |

| Primary cutaneous follicle centre lymphoma |

| Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, leg type |

| Primary cutaneous diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, other intravascular large B-cell lymphoma |

| Precursor haematologic neoplasm |

| CD4+/CD56 + haematodermic neoplasm (blastic NK cell lymphoma) |

WHO-EORTC: World health organisation-European organisation for reseacrh and treatment of cancer classification, NK: natural killer cell.

Etiopathogenesis

As with almost all malignancies, ‘two-hit’ model applies to CTCL as well and is believed to be due to an underlying genetic predisposition triggered by environmental factors. Oncogene RLTPR (also known as CARMIL2) encodes a newly discovered protein in the T-cell receptor (TCR) signalling pathway, which increases binding of RLTPR to downstream mediators of the NF-κB signalling pathway, selectively upregulates this pathway in activated T-cells and ultimately results in the increased production of IL-2 by 34-fold.4 Genetic profiling of 220 patients of CTCL found 55 driver mutations implying 14 biologically relevant pathways.4 Affected pathways broadly include those involved in T-cell function, cell cycle, activation, migration and differentiation; chromatin modification; survival; and proliferation. Most genes are affected because of the somatic copy number variations (SCNV). Noteworthy findings were decreased interferon gamma (γ-IFN), interleukin-2 (IL-2), nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT), regulatory subunit of phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PIK3R1) expression in leukaemic cells; and gain of expression of histone deacetylase-9 (HDAC9) and loss of function of tumour suppressor genes like TP53 and CDKN2A. Interestingly, differences in the chromatin accessibility landscape among leukaemic cells predicted responses to HDAC inhibitors.5

Environmental triggers for MF/SS such as infections leading to a ‘second hit’ were first put forward by Tan et al. as per the chronic antigen stimulation theory.6 It is believed to lead to clonal proliferation of T-cells leading to malignant transformation. Staphylococcus aureus antigen is believed to be able to act as a superantigen and stimulate proliferation of malignant T-cells.7 The studies exploring the direct relation of other infectious agents (including HTLV-1, polyoma viruses and EBV) leading to MF/SS have yielded contradictory results.8,9 Patients with familial inheritance of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis may be at higher risk for MF/SS.10,11 Parapsoriasis and pityriasis lichenoides spectrum consisting of pityriasis lichenoides chronica (PLC) and pityriasis lichenoides et varioliformis acuta (PLEVA) have been reported to progress to MF. The likelihood of progression of large plaque parapsoriasis is approximately between 10% and 35%, which is much greater than that of small plaque parapsoriasis.12 The numbers of pityriasis lichenoides spectrum cases progressing to MF are scant in literature and are limited to isolated case reports.13 Although there are many drugs suspected to be implicated in the etiology of MF/SS, hydrochlorothiazide in particular have been shown to be a putative agent causing MF.14,15 UVB causes the chlorine atom in hydrochlorthiazide to dissociate, creating free radicals that react with DNA, proteins and lipids leading to formation of novel keratinocyte antigens triggering an inappropriate T-cell response resulting in CTCL.15 Of late, dupilumab, an IL-4 receptor inhibitor, an approved biologic for atopic dermatitis, has been reported to trigger MF as well as SS.16 However, it is still not known whether MF/SS was actually triggered or it was misdiagnosed as atopic dermatitis in the first place.17

Recent works on some subtle pathogenetic differences between MF and SS have led to some fascinating observations. The average adult skin under normal physiological conditions contains about 20 billion T-cells.18 Most of these are memory T-cells, whereas only about 5% are naïve T-cells.19 The naïve T-cells are exposed to antigens in the lymph nodes draining the skin by the antigen presenting cells (APCs), following which they proliferate clonally as effector T-cells and begin to express the skin homing cutaneous lymphocyte antigen (CLA) and the C-C chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4).20 Once the cognate antigens are neutralised by these effector T-cells, they differentiate into memory T-cells.21 CCR7 and L-selectin helps the T-cells migrate from skin to the circulation. Skin central memory T-cells (TCM) are CCR7+/L-selectin+, which directs them for circulation in skin, lymph nodes and blood.22 Skin resident memory T-cells (TRM) are CD4+ but lack CCR7 and L-selectin. Hence they rarely circulate out of the skin. Another subset of T-cell known as migratory memory T-cell (TMM) express CCR7 but not L-selectin and perhaps represent an intermediate phenotype recirculating more slowly out of the skin to blood compared with the TCM.22 In MF and SS, the demonstration of different T-cell surface phenotypes backed by molecular profiles support the hypothesis that the origin of these malignancies are distinct memory T-cell subsets – TRM in MF and the TCM in SS. The molecular properties of these T-cell subtypes correlate well with clinical manifestations of MF and SS. Skin TRM are non-migratory cells, and hence the patients present clinically with fixed skin lesions in MF.23 However, TCM recirculate between skin, lymph node and blood and present clinically as SS with diffuse erythema, lymphadenopathy and leukaemic disease.23 Apart from disruption of the skin barrier function by erythroderma and ulcerated tumours, patients with MF/SS in advanced stages are vulnerable to bacterial infection because of ineffective local and systemic immune response to pathogens due to clonal expansion of T-cells. It has been found that immune-dysregulation is partly driven by maladies in the JAK/STAT signalling pathway.24 The microenvironment plays a significant role in the stability or progression of CTCL. In the early stages of MF, the neoplastic cell numbers and multiplication are kept in check by reactive T-helper (Th) 1 and CD8+ T-lymphocytes, which constitute an anti-tumour defence. A shift from a Th1 to a Th2 response contributes to unabated tumour cell growth and multiplication leading to progression.25 SS is an aggressive variant of CTCL and is a Th2 type disease exhibiting exhaustion of antitumour defence with overwhelming polarity towards levels of IL-4, IL-5 and IL-1 with almost no emphasis on Th1 cytokines such as IL-2 and IFN-γ.25 This microenvironment favours proliferation of malignant cells, increased survival, angiogenesis and tissue remodelling.

Clinical features

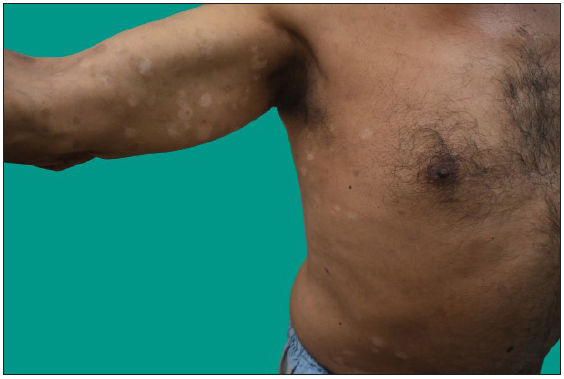

The most common stage of presentation of MF is the patch stage followed by plaque stage where patients present with long-standing asymptomatic scaly macules mainly over the trunk, especially over the photo-protected areas [Figure 1a]. Patch/plaque stage of MF is either asymptomatic or itchy.26 Itching can be severe in advance stages of the disease, which is especially profound in erythrodermic MF and SS masquerading as adult atopic dermatitis.27 The grade of itching is associated with poor quality of life, fatigue and is a negative predictor for survival.26 Since the early stage of MF is often asymptomatic, it is ignored by patients and overlooked by the dermatologists. Since there is considerable clinical as well histopathological overlap between MF and other inflammatory dermatoses, the diagnosis is challenging for both the clinician as well as the pathologist. It may be clinically as well as histopathologically misdiagnosed with papulosquamous and eczematous diseases like psoriasis, parapsoriasis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, chronic actinic dermatitis, asteatotic dermatitis and adult onset AD. Most often, patients presenting in the patch stage are likely to undergo multiple biopsies for years before a definitive diagnosis of MF. The median time from symptom onset to diagnosis in a retrospective series is three to four years, but may exceed by decades.28

- Patch stage of mycosis fungoides: multiple asymptomatic hypopigmented macules mainly over the photoprotected areas.

MF clinical variants

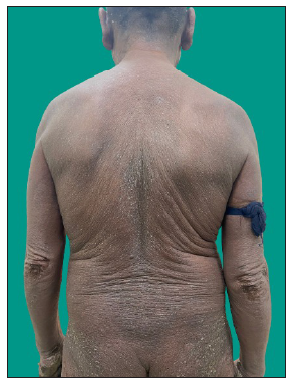

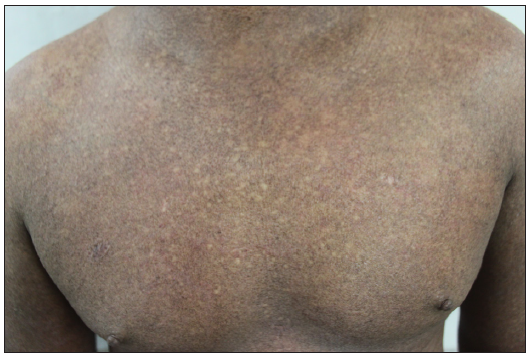

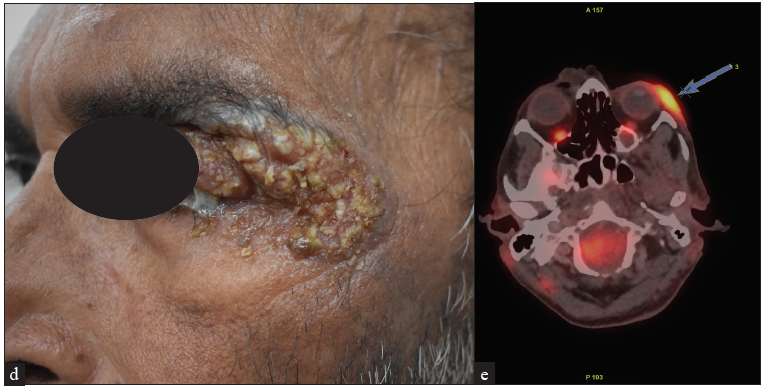

MF presents with varied morphology and consequently have been classified into clinical variants.29 The classical MF usually presents as erythematous (with variegation of colour or poikiloderma) scaly patches in photo-protected areas. The number and size may increase over time or rarely regress spontaneously. Hypopigmented MF is characterised by hypopigmented macules without atrophy. It is more discernible in patients with skin of colour and is the most frequent variant seen in, but not limited to childhood. It has a better prognosis than the classic form as it responds favourably to phototherapy with narrowband UV-B. The patches may become infiltrated or indurated over time to form plaques and further into nodules. The nodules may also develop de novo (tumour d’emblee). Erythrodermic MF variant usually results from unchecked disease activity from patch stage and lack haematological involvement characteristic of SS [Figure 1b]. Apart from the classical MF, other World Health Organisation (WHO)-recognised variants include folliculotropic MF, pagetoid reticulosis (PR) and granulomatous slack skin disease (GSSD). The folliculotropic MF presents with involvement of head and neck area in the form of crusted, scaly, erythematous, indurated, alopecic plaques [Figures 2a–2c]. Granulomatous slack skin disease (GSSD) is characterised by redundant skin folds, which show a predilection towards flexural areas such as the axilla and groin. Histologically, it shows a granulomatous T-cell infiltrate with loss of elastin fibres. Pagetoid reticulosis (PR) presents as a solitary hyperkeratotic plaque usually on the extremities [Figure 3a]. Two variants have been described – the Woringer-Kolopp disease, which presents with a single lesion, often on the extremities, with good prognosis and the generalised type or Ketron-Goodman disease with disseminated lesions with a poor prognosis. Other uncommon variants are ichthyosiform, papular, pustular, bullous, pityriasis lichenoides like, palmoplantar, psoriasiform, poikilodermatous, pigmented purpuric dermatoses like, figurate erythema like, verrucous, acanthosis nigricans like, bullous, interstitial and granulomatous MF.29 Poikilodermatous MF presents with extensive poikilodermatous lesions over the body [Figure 3b].

- Sézary syndrome presenting as erythroderma.

- (a and b) Folliculotropic MF involving retroauricular area, scalp, face and trunk. (c) Large cell transformation presenting as ulcer on scalp.

- Woringer Kolopp variant of pagetoid reticulosis presenting as a solitary plaque on the left foot.

- Poikilodermatous MF presenting as diffuse poikilodermatous changes all over the body.

Evaluation of suspected mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome

Histopathological examination

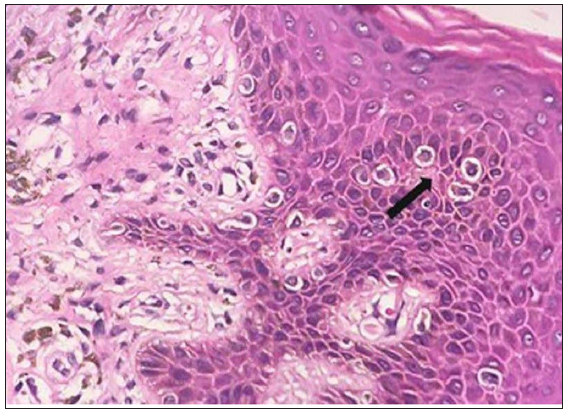

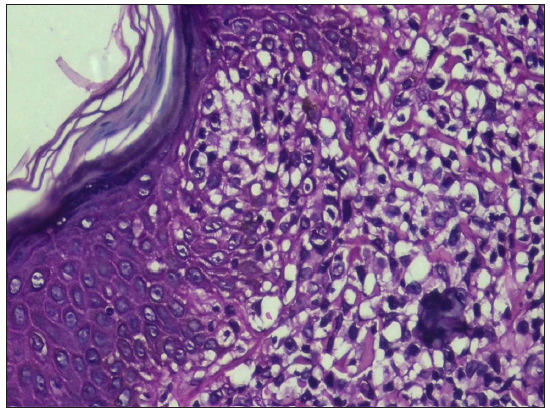

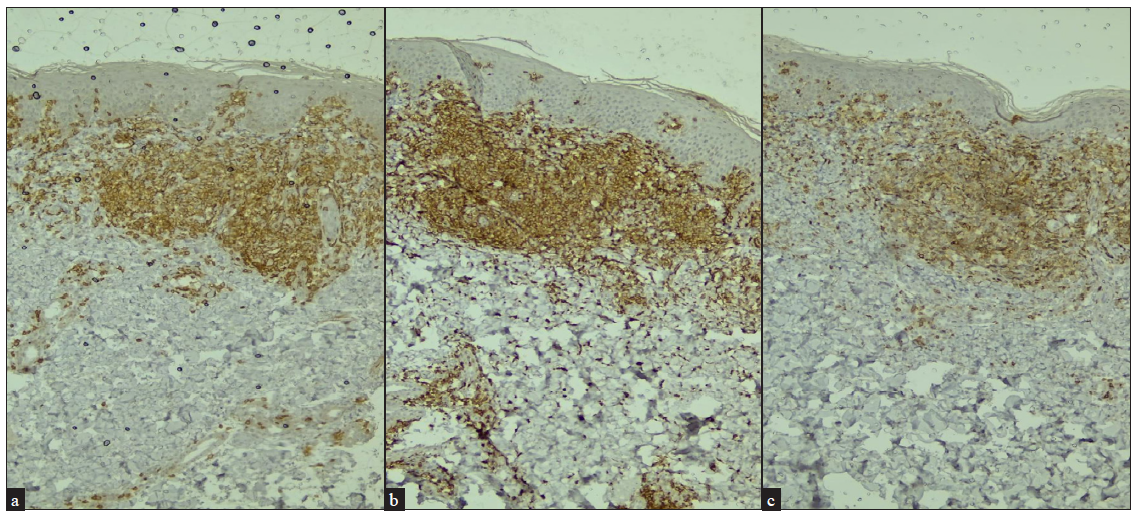

Biopsy remains the gold standard for diagnosis of MF/SS. Since application of topical steroids, administration of ultraviolet light therapy and systemic immunomodulators diminish critical histopathologic findings, it is prudent to stop all therapy for at least two weeks before a biopsy is performed. To increase the diagnostic yield, nodules should be preferred, followed by plaques and lastly patches. If there are only patches, a careful clinical examination should be carried out to look for any indurated areas in the patches. The earliest histopathological feature in the patch stage of MF is lining up of lymphoid cells at the dermoepidermal junction giving rise to ‘toy soldier’ appearance [Figure 4a]. As disease progresses from patches to plaques, prominent epidermotropism develops which is characterised by an invasion of the epidermis by atypical lymphoid cells lying either singly or in clusters forming Pautrier microabscesses30 [Figure 4b]. Atypical T-cells have irregular nuclear outline (cerebriform) with condensed and darkly stained nucleoli. There is paradoxical loss of epidermotropism in the tumour stage, which is believed to occur due to a loss of expression of integrins like αEβ7.31 The infiltrate predominantly consists of small cerebriform cells with a variable mix of lymphoblasts, immunoblasts and medium- or large-sized pleomorphic cells with hyperchromatic nuclei. Several benign dermatoses like pseudolymphomas, actinic reticuloid and parapsoriasis mimic early MF and must be distinguished by a nuanced study of clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemistry (IHC) features.31,32

- Black arrow shows discrete lining of atypical lymphocytes at the dermo-epidermal junction. (Toy soldier appearance in the patch stage of MF). (Haematoxylin & eosin, 40x).

- Collection in atypical lymphocytes in clusters in the epidermis (Pautrier’s microabscesses) from a case of plaque stage of MF. (Haematoxylin & eosin, 40x)

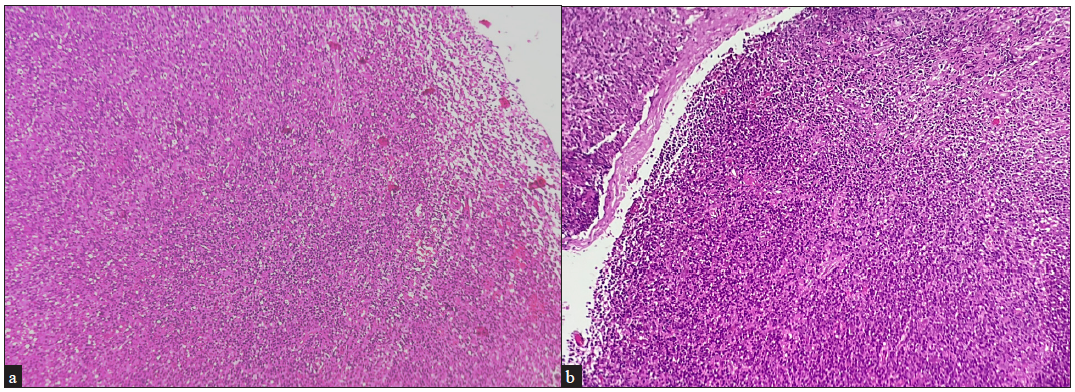

Although the utility of skin biopsy is limited to diagnosis, the histopathology of lymph nodes dictates the staging of the disease [Figures 5a–5d]. Any clinically enlarged lymph node is an indication for biopsy, especially when it is draining the area of the suspected lesion. The International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL)/EORTC revision (2022) defines clinically abnormal peripheral nodes as ≥1.5 cm or any palpable peripheral node regardless of size that on physical examination is firm, irregular, clustered or fixed.33 If there are multiple sites with enlarged nodes, the order of preference for lymph node biopsy is cervical, axillary and lastly inguinal nodes, since cervical nodes have a higher chance of lymphomatous involvement than others.34 A fluorodeoxyglucose-18 (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) carried out prior to the lymph node biopsy may help choose the one with highest radioactive uptake to increase the diagnostic yield. There is no definitive role of fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) from a lymph node in the MF/SS, as it cannot delineate any effacement of the lymph node architecture which is required for staging the disease in lymph nodes.

- Scanner and low magnification view of a lymph node showing complete effacement of the lymph node architecture (a) Haematoxylin & eosin, 10x), (b) (Haematoxylin & eosin, 20x).

- Lymph node biopsy (c) Diffuse infiltration of the lymph node by lymphoid cells lying singly as well as in clusters (Haematoxylin and eosin, 20x), (d) These lymphocytes are irregular in morphology with atypical nuclei with coarse vesicular chromatin (Haematoxylin and eosin, 40x).

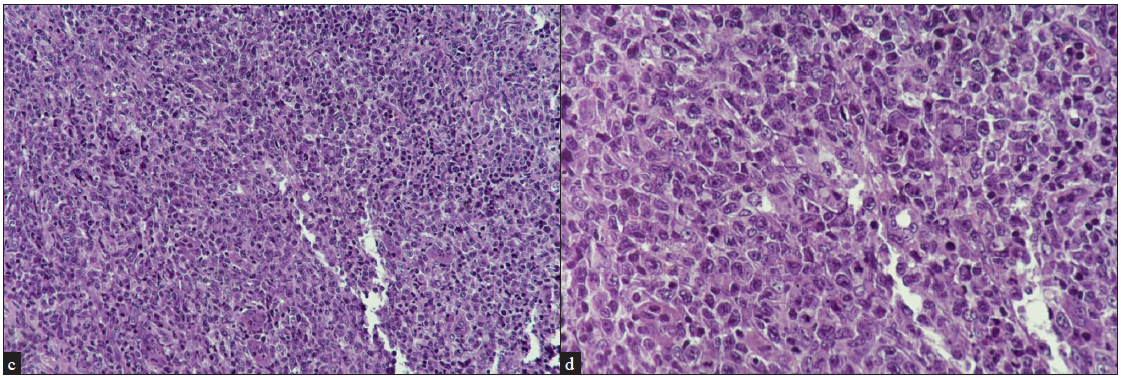

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is usually performed in all suspected cases of MF/SS. It is recommended to perform at least the following T-cell markers: CD2, CD3, CD4, CD5, CD7 and CD8; and B cell marker: CD20. CD30 is also indicated in cases where large cell transformation, anaplastic lymphoma or lymphomatoid papulosis are considered as differential diagnoses. Typical IHC profiles are CD3+, CD4+, CD5+ and CD8− with relative loss of expression of CD7 [Figures 6a–6c].

- Immunohistochemistry (IHC) on skin biopsy shows (a) CD3+, (b) CD4+ and (c) relative loss of expression of CD7 (20x).

T-cell receptor gene rearrangement studies

The polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based methods are done to look for clonal rearrangements of the TCR in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded biopsy specimens. It may be a skin or a lymph node biopsy or even a peripheral blood sample in case of SS. However, some benign dermatoses and infections may also possess pseudo-monoclonality which may show positive results on gene rearrangement.35,36 Traditionally, the southern blot technique was the only method to determine clonality in TCR gene rearrangement but with low sensitivity.37 It also required large samples of fresh frozen tissues. Since the early 1990s, more sensitive PCR-based techniques have been developed and are preferred due to higher sensitivity.38 But PCR test is still of insufficient sensitivity, particularly at early stages, because early lesions often do not contain sufficient numbers of clonal T-cells leading to false negative report. To overcome this shortcoming, the next-generation high throughput sequencing (NGS) is presently preferred, because not only it determines the number of individual T-cell clones present in a given sample, but it also determines the quantification and relative proportions of specific clones. It has higher sensitivity as compared to PCR even in the early stages of MF.39 Moreover, NGS allows dermatologists to follow the specific clones while monitoring recurrence and progression of the disease.7 A tumour clone frequency of >25% in skin biopsy is a predictor for disease progression.40

Peripheral Blood Smear

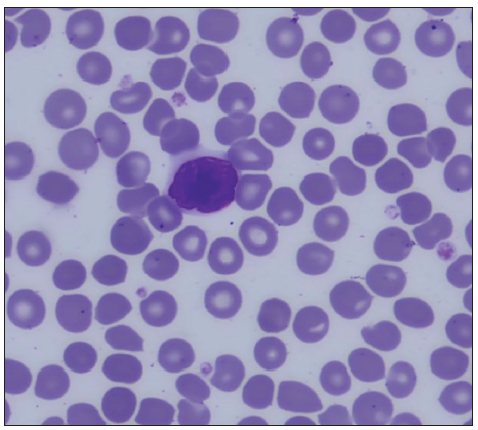

Peripheral blood smear (PBS) is a must in all cases of suspected MF, especially in erythroderma. Apart from looking for anaemia, which may occur in any chronic disease, the chief purpose of PBS, especially in cases of erythroderma, is to look for Sézary cells. They are large (12–16 μm) abnormal lymphocytes with a giant nucleus occupying almost the whole cell by pushing the cytoplasm to merely a thin peripheral rim. They are called cerebriform cells because the nuclear membrane is thrown into folds likened to sulci and gyri of the brain [Figure 7a]. Although Sézary cells may be seen in many inflammatory disorders causing eythroderma, it is the significant number of Sézary cells which clinches the diagnosis of SS. The significant number of Sézary cells is defined as ≥1000 cells/μl or Sézary cells comprising more than 20% of the total lymphocyte count.41

- Sézary cell in peripheral blood smear.

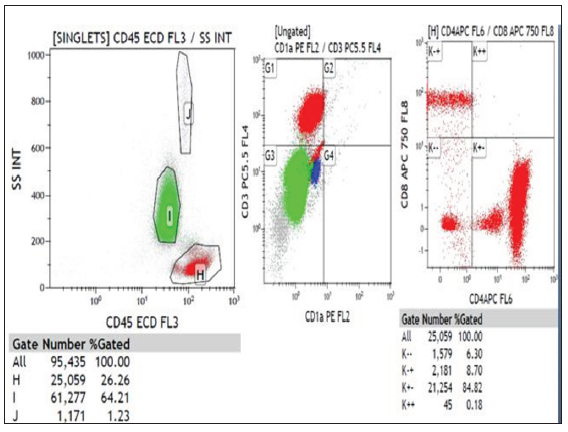

Flow cytometry

A flow cytometry should be performed on the peripheral blood in all cases of erythroderma with Sézary cells. It is done to correlate if clonality is present in blood in addition to skin, as found out in IHC. It is recommended to stop any systemic immunosuppressive agents for a couple of weeks since they may affect the PBS and flow cytometry reports. There are two parameters which are important to look for: CD4/CD8 ratio and percentage of CD7 and CD26 positive cells. CD4/CD8 ratio >10 is diagnostic of SS [Figure 7b]. Increase in CD4+ cells with an abnormal phenotype (≥40% CD4+/CD7‒ or ≥30% CD4+/CD26‒) has been suggested. The loss of CD7 (≥40%) and/or CD26 (≥80%) is sensitive (>80%) and highly specific (100%) for SS.42

- Immunophenotyping of whole blood shows 26% CD45 bright population of lymphoid cells, and CD4/CD8 ratio >10, diagnostic of Sezary syndrome.

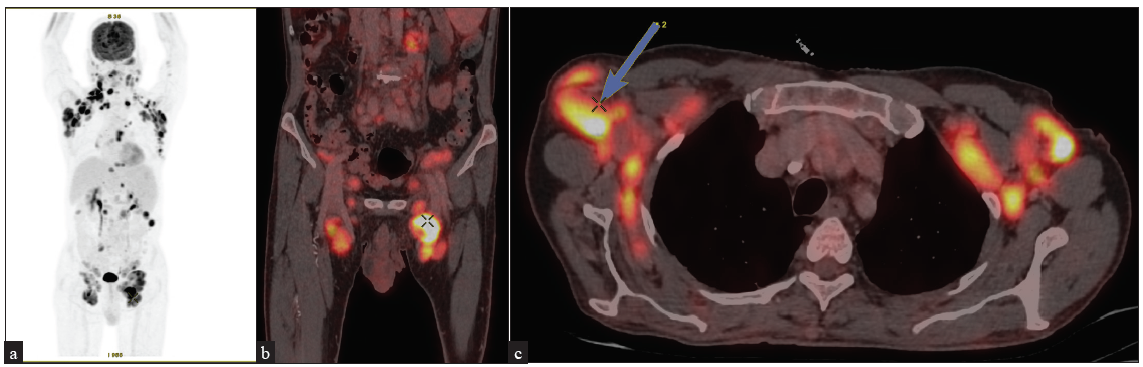

Radiological investigations

In T1/patch stage patients who are otherwise healthy and in selected some patients of T2 stage disease, a chest X-ray and/or ultrasound of the peripheral lymph nodes may be performed to rule out adenopathy. In patients with more advanced diseases, a FDG-PET scan is necessary for evaluation of lymphadenopathy and visceral metastasis43 [Figures 8a–8e]. A recent study has concluded that radiological screening improves detection of lymph node involvement to 18% from 5% over clinical examination.44

- (a) Maximum intensity projection of 18F-FDG PET in a patient of mycosis fungoides shows increased uptake in bilateral cervical, axillary, mediastinal, para-aortic, retro-peritoneal, iliac and inguinal lymph nodes. (b, c) Axial and coronal CT, PET and fusion PET/CT images shows increased 18F-FDG uptake in bilateral inguinal, iliac and axillary lymph nodes. (PET: positron emission tomography, FDG: fluorodeoxyglucose.)

- (d) Plaque stage of MF on the left peri-orbital area and (e) Increased 18F-FDG uptake in the plaque. (FDG: Fluorodeoxyglucose.)

A list of specific investigations with their relevance directed at CTCL/SS is given in Table 2.

| S No | Investigations | Relevance |

|---|---|---|

| Complete blood count | Anaemia, raised total leucocyte count may indicate leukaemic variant of CTCL, that is, Sézary syndrome. | |

| Peripheral blood smear | Sézary cell count, anaemia. | |

| Liver function test | Necessary for baseline, metastasis and therapeutics. | |

| Renal function test | Necessary for baseline and therapeutics. | |

| Serum lactate dehydrogenase | Independent prognostic factor. | |

| X-ray chest | Necessary for baseline status and metastasis. | |

| Ultrasound abdomen | For organomegaly and metastasis in liver and spleen. | |

| Skin biopsy |

H&E stain for atypical lymphocytes, toy soldier appearance, epidermotropism, Pautrier’s microabcesses. Typical immunohistochemistry profile is CD3+, CD4+, CD5+ and CD8− with relative loss of expression of CD7. CD30 for large cell transformation. |

|

| Lymph node biopsy | If clinically enlarged lymph nodes, H&E stain for atypical lymphocytes, Pautrier’s micro-abcesses, partial or complete effacement of lymph nodes. IHC – same as skin biopsy | |

| Flow cytometry |

In case of suspected leukaemic involvement/Sézary syndrome CD4/CD8 ratio and percentage of CD7 and CD26 positive cells. CD4/CD8 ratio >10 is diagnostic of SS. |

|

| FDG-PET scan | A must in any stage advanced than patch or limited plaque stage for lymph node and visceral involvement. | |

| T-cell receptor (TCR) gene rearrangement studies on either skin/lymph node biopsy specimen or peripheral blood | To look for clonal rearrangements of the TCR – poor prognostic factor by PCR. A tumour clone frequency of >25% in skin biopsy is a predictor for disease progression. | |

| Bone marrow biopsy | Bone marrow biopsy is recommended in patients with MF and SS who have B2 blood involvement or unexplained haematologic abnormalities. It is done to look for metastasis in bone marrow. | |

| Liver biopsy | Any suspicious lesion (metastasis) on radiology of liver (CT/FDG-PET) must be confirmed by liver biopsy. |

Investigations up to serial number 8 must be done in both early and advanced MF/CTCL, whereas investigations beyond serial number 8 are indicated in advanced stages only. A clinically significant lymph node must be biopsied whenever present

Conclusion

CTCL, MF and SS pose significant diagnostic challenge due to its varied morphology and clinical features. A thorough background knowledge of the etiopathogenesis and a robust, systemic clinical examination is critical in planning the management of the patient.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of AI-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- Baron Jean-Louis Alibert (1768–1837) and the first description of mycosis fungoides. J BUON. 2014;19:585-8.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morphologic and functional properties of the atypical T lymphocytes of the Sezary syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 1974;49:558-66.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The 2018 update of the WHO-EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas. Blood. 2019;133:1703-14.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Genomic analysis of 220 CTCLs identifies a novel recurrent gain-of-function alteration in RLTPR (p.Q575E) Blood. 2017;130:1430-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Chromatin accessibility landscape of cutaneous T cell lymphoma and dynamic response to HDAC inhibitors. Cancer Cell. 2017;32:27-41.e4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Mycosis fungoides—a disease of antigen persistence. Br J Dermatol. 1974;91:607-16. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1974.tb12449.x

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathogenesis of cutaneous T cell lymphoma: Involvement of staphylococcus aureus. J Dermatol. 2022;49:202-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serological HTLV profile in patients with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma from a reference center in southern Brazil. Int J Dermatol. 2021;60:e501-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Infectious agents in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:423-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Risk of lymphoma in patients with atopic dermatitis and the role of topical treatment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:992-1002.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The risk of lymphoma in patients with psoriasis. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2194-201.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parapsoriasis—A diagnosis with an identity crisis: A narrative review. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12:1091-102.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Mycosis fungoides following pityriasis lichenoides: An exceptional event or a potential evolution? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58:307.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drug-induced reversible lymphoid dyscrasia: A clonal lymphomatoid dermatitis of memory and activated T cells. Hum Pathol. 2003;34:119-29.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hydrochlorothiazide and cutaneous T cell lymphoma: Prospective analysis and case series. Cancer. 2013;119:825-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dupilumab-associated mycosis fungoides: A cross-sectional study. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2561-69.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Progression of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma after dupilumab: Case review of 7 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:197-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The vast majority of CLA+ T cells are resident in normal skin. J Immunol. 2006;176:4431-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A three-dimensional atlas of human dermal leukocytes, lymphatics, and blood vessels. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:965-74.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Skin-resident T cells: the ups and downs of on site immunity. J Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:362-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Resident memory T cells in human health and disease. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:269rv1.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Human skin is protected by four functionally and phenotypically discrete populations of resident and recirculating memory T cells. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7:279ra39.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Sezary syndrome and mycosis fungoides arise from distinct T-cell subsets: A biologic rationale for their distinct clinical behaviors. Blood. 2010;116:767-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Deregulation in STAT signaling is important for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) pathogenesis and cancer progression. Cell Cycle. 2014;13:3331-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The role of tumor microenvironment in the pathogenesis of sézary syndrome. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:936.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Pruritus in cutaneous t-cell lymphoma: A review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;67:760-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- A comprehensive update of the atypical, rare and mimicking presentations of mycosis fungoides. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11:1931-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The PROCLIPI international registry of early-stage mycosis fungoides identifies substantial diagnostic delay in most patients. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181:350-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinicopathologic variants of mycosis fungoides. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2017;108:192-208.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darier, Pautrier, and the “microabscesses” of mycosis fungoides. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:320-1.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinicopathological spectrum of cutaneous lymphomas and distinction of early mycosis fungoides from its mimics – a retro-prospective descriptive study from southern India. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2022;13:737-46.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Histologic mimickers of mycosis fungoides: A review. J Cutan Pathol. 2007;34:519-25.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primary cutaneous lymphoma: Recommendations for clinical trial design and staging update from the ISCL, USCLC, and EORTC. Blood. 2022;140:419-37.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Revisions to the staging and classification of mycosis fungoides and Sezary syndrome: A proposal of the International Society for Cutaneous Lymphomas (ISCL) and the cutaneous lymphoma task force of the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Blood. 2007;110:1713-22.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pseudo-spikes are common in histologically benign lymphoid tissues. J Mol Diagn. 2000;2:145-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Analysis of t-cell receptor gene rearrangement for predicting clinical outcome in patients with cutaneous t-cell lymphoma: A comparison of southern blot and polymerase chain reaction methods. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:1107-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southern blot analysis of clonal rearrangements of T-cell receptor gene in plaque lesion of mycosis fungoides. J Invest Dermatol. 1989;93:626-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The polymerase chain reaction in the diagnosis of early mycosis fungoides. J Pathol. 1997;182:282-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Next-generation sequencing technologies for early-stage cutaneous t-cell lymphoma. Front Med (Lausanne). 2019;6:181.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- High-throughput sequencing of the T cell receptor β gene identifies aggressive early-stage mycosis fungoides. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10:eaar5894.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Blood will tell: Profiling Sézary syndrome. Blood. 2021;138:2450-1.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Sézary syndrome: Hematologic criteria. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2003;17:1367-89. viii

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preliminary discussion on the value of (18)F-FDG PET/CT in the diagnosis and early staging of non-mycosis fungoides/Sézary’s syndrome cutaneous malignant lymphomas – PubMed. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25982461/ [last accessed: 2023. Oct 20].

- Should we be imaging lymph nodes at initial diagnosis of early-stage mycosis fungoides? Results from the PROspective Cutaneous Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (PROCLIPI) international study. Br J Dermatol. 2021;184:524-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]