Translate this page into:

Nannizzia incurvata as a rare cause of favus and tinea corporis in Cambodia and Vietnam

Corresponding author: Prof. Pietro Nenoff, Mölbiser Hauptstraße 8, 04571 Rötha, OT Mölbis, Germany. pietro.nenoff@gmx.de

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Uhrlaß S, Mey S, Storch S, Wittig F, Koch D, Krüger C, et al. Nannizzia incurvata as a rare cause of favus and tinea corporis in Cambodia and Vietnam. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2021;87:516-21.

Abstract

Nannizzia (N.) incurvata (formerly Microsporum incurvatum) represents a geophilic dermatophyte which has been previously classified as belonging to the species complex of N. gypsea (formerly Microsporum gypseum). A 42-year-old Vietnamese female from Saxony, Germany, suffered from tinea corporis of the right buttock after she returned from a 2-week-visit to her homeland Vietnam. From skin scrapings of lesions, N. incurvata grew on Sabouraud’s dextrose agar. Treatment by ciclopirox olamine cream twice daily for 4 weeks was successful. A 6-year-old Cambodian boy living near river Mekong with contact history to chicken, dogs and cattle suffered from tinea faciei and capitis. Symptoms of the favus-like tinea capitis and tinea faciei were erythema and scaly patches with areas of alopecia. N. incurvata grew on Sabouraud's dextrose agar. The boy was treated with oral terbinafine 125 mg daily, topical miconazole cream and ketoconazole shampoo. The symptoms healed within 4 weeks of treatment. Cultivation of the samples revealed growth of N. incurvata. For confirmation of species identification, the isolates were subject to sequencing of ITS (internal transcribed spacer) region of the rDNA, and addition of the “translation elongation factor 1 α” (TEF 1 α) gene. Sequencing of the ITS region showed 100% accordance with the sequence of N. incurvata deposited at the NCBI database under the accession number MF415405. N. incurvata is a rare, or might be underdiagnosed geophilic dermatophyte described in Sri Lanka and Vietnam until now. This is the first isolation of N. incurvata in Cambodia, and the first description of favus in a child due to this dermatophyte.

Keywords

Dermatophyte

DNA-sequencing

terbinafine

tinea capitis

tinea faciei

Introduction

Nannizzia (N.) incurvata (formerly Microsporum [M.]incurvatum) represents a geophilic dermatophyte previously classified as belonging to the species complex of N. gypsea (formerly M. gypsea). According to the new taxonomy of dermatophytes, N. incurvata has to be considered as a separate species.1 Due to its geophilic character and origin, this fungus can be transmitted from soil to human beings causing tinea corporis and tinea manuum. Until now, there are only few descriptions of infections in animals and humans.2 Two patients with an infection caused by N. incurvata are presented in this study. Both N. incurvata strains were identified microscopically by culture and by Sanger sequencing of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region of the rDNA, and addition of the “translation elongation factor 1 α“ (TEF 1 α) gene.

Case Reports

Patient 1

History and clinical picture

A 42-year old Vietnamese female from Saxony, Germany, suffered from tinea corporis of the right buttock after she returned from a 2-week visit to her homeland Vietnam. Annular scaly dry erythematous lesions appeared in the region of the right hip [Figure 1a]. Family members of the woman were not affected.

- Tinea corporis due to Nannizzia incurvata in a 42-year-old woman after a journey to Vietnam. Centrifugal erythematosquamous lesion in the region of the right hip

Mycological diagnostics

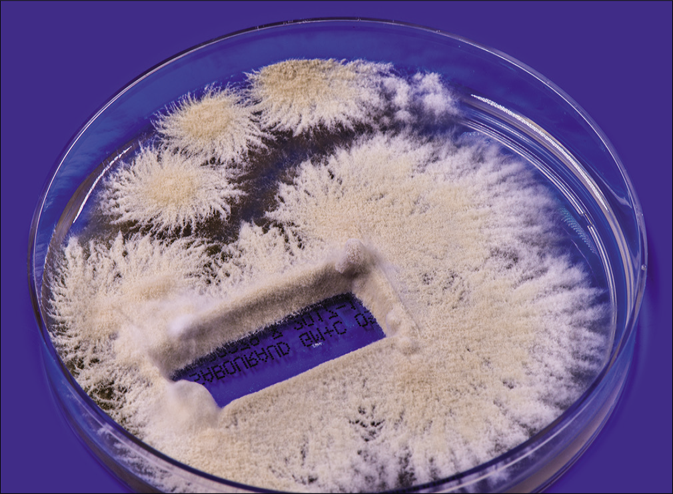

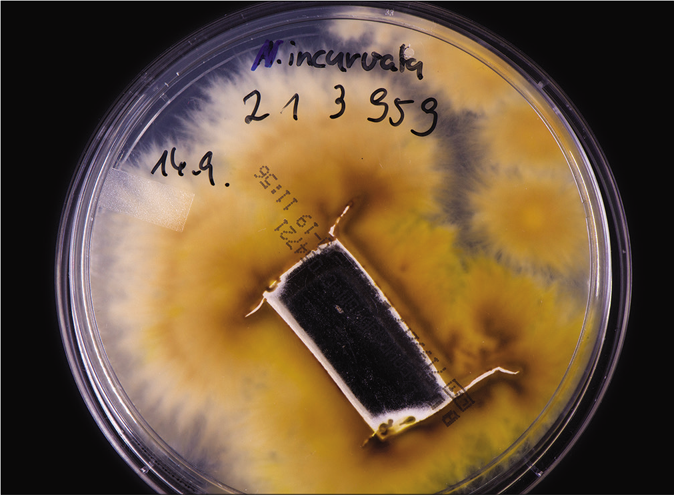

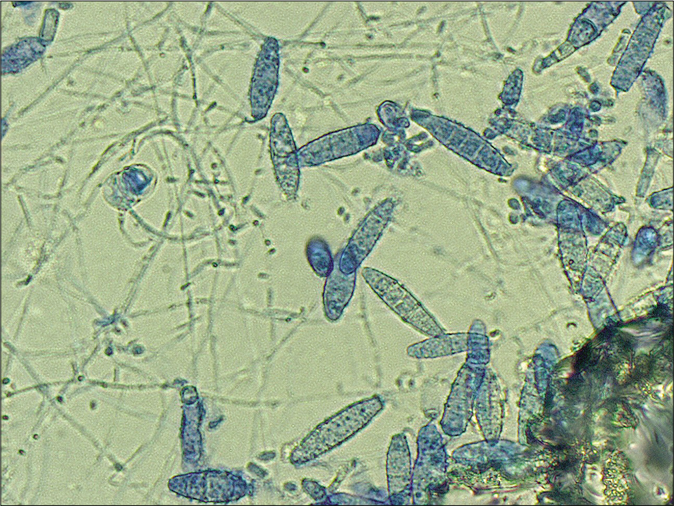

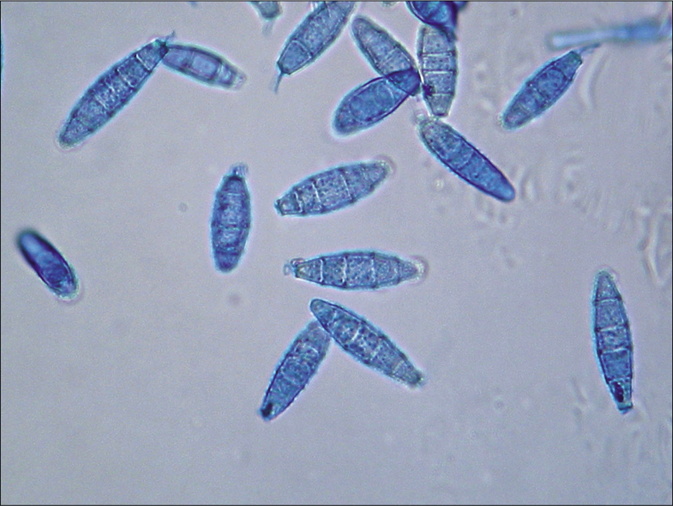

From skin scrapings of the centrifugal lesions, the cultures on Sabouraud’s dextrose agar with and without cycloheximide (Actidion®), fast-growing fungal colonies developed. The thallus of the dermatophyte was flat, fast-growing, initially white, but quickly becoming beige to cinnamon brown stained [Figure 1b]. The surface appeared powdery with spreading peripheral hyphae bundles, while the reverse was yellowish-brown stained [Figure 1c]. Microscopically, a multitude of spindle-like (ellipsoid), relatively short (30–50 μm long), thick-walled, echinulate macroconidia with half-round tops were seen [Figure 1d]. They were present in bundles at the end of hyphae or also as single macroconidia at the end of a conidiophore. An abundance of macroconidia were located separately on all mycelia. Clavulate and sessile microconidia together with single chlamydospores extend alongside the hyaline septate hyphae [Figure 1e]. Based on these macro-morphological and microscopic features, the geophilic dermatophyte species N. gypseum was suspected. Other members of the so-called N. gypsea-complex, however, were considered as differential diagnoses, e. g., N. fulva and N. incurvata.

- Tinea corporis due to Nannizzia incurvata in a 42-year-old woman after a journey to Vietnam. Nannizzia incurvata isolated from the skin lesion of the aforementioned patient

- Tinea corporis due to Nannizzia incurvata in a 42-year-old woman after a journey to Vietnam. Reverse side of the colonies

- Tinea corporis due to Nannizzia incurvata in a 42-year-old woman after a journey to Vietnam. Microscopically, a multitude of spindle formed (ellipsoid), relatively short (30–50 μm long), thick walled, echinulate macroconidia with half round tops were seen. Clavulate and sessile microconidia alongside the hyaline septate hyphae (Lactophenol cotton blue preparation)

- Macroconidia together with single big chlamydospore (Lactophenol cotton blue preparation)

Treatment

There was no improvement after treatment with clotrimazole + betamethasone dipropionate ointment (due to wrong diagnosis as a psoriasiform inflammatory dermatosis), ciclopirox olamine cream, and mometasone furoate. After changing to ciclopirox olamine cream monotherapy twice daily for 4 weeks, the tinea corporis lesions healed.

Patient 2

History and clinical picture

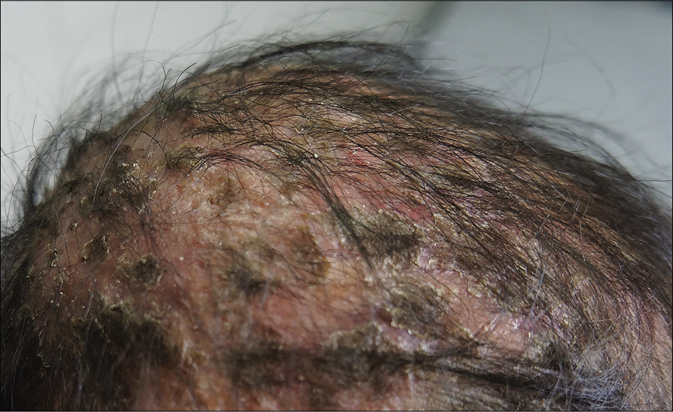

A 6-year old Cambodian boy living near river Mekong (water and forest region) at a village with history of contact with chicken, dogs and cattle suffered from tinea faciei and tinea capitis. Family members were not affected. The disease started at an age of four years. Initial lesion was on the scalp, later extended to the face [Figure 2a]. Symptoms of the favus-like tinea capitis and tinea faciei were erythema, scaly patches with areas of alopecia, but no pustules [Figure 2b]. Main complaints were pruritus and alopecia. The child was treated first by a pediatrician for 12 weeks with griseofulvin 250 mg once daily, but without improvement. Hepatitis B and C and HIV tests were negative. In Microsporum or Nannizzia species, a typical green-yellowish fluorescence should be expected. From skin scrapings, N. incurvata grew on Sabouraud's dextrose agar. Later on, at the department of dermatology in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, the boy received oral terbinafine 125 mg daily, topical miconazole, ketoconazole shampoo, oral cetirizine and multivitamin preparations. The symptoms improved after 2 weeks of treatment. Treatment was continued for 1 month.

- Tinea capitis and tinea faciei in a 6-year-old Cambodian boy living in a rural region of the country.Favus-like tinea capitis with erythema, scaly patches within huge areas of alopecia

- Tinea capitis and tinea faciei in a 6-year-old Cambodian boy living in a rural region of the country. Tinea faciei with hyperkeratotic, papular and dry squamous lesions in the central parts of the face

- Tinea capitis and tinea faciei in a 6-year-old Cambodian boy living in a rural region of the country. Spindle formed (ellipsoid) macroconidia with half-round tops. Lactophenol cotton blue preparation

- Tinea capitis and tinea faciei in a 6-year-old Cambodian boy living in a rural region of the country. Clavulate microconidia at the hyphae. Lactophenol cotton blue preparation

Molecular identification of the dermatophyte species

Molecular biological diagnostics

For confirmation of the suspected dermatophyte species, sequencing of the ribosomal DNA (rDNA), mainly the regions ITS 1, 5.8S rRNA, ITS 2 and the translation elongation factor (TEF)-1 α gene were done for both strains as described3-5 to identify dermatophytes at a species level via the extracted DNA from fungal cultures. This required PCR amplification of a ∼ 900 bp DNA fragment using universal primers that bind to flanking pan-fungal sequence regions. The following gene sequences were used as probes for sequencing of the ITS region of the rDNA:

V9G 5’-TTACGTCCCTGCCCTTTGTA-3’ and LSU266 5’-GCATTCCCAAACAACTCGACTC-3’.

The length of the analyzed region in the TEF-1 α gene varied from 709 to 769 nucleotides among the various dermatophyte species. Primers EF1a-F 5’CACATTAACTTGGTCGTTATCG 3’ and EF1a-R 5’CATCCTTGGAGATACCAGC3’ were used for sequencing.3

The sequence of each strain was compared to sequences of type strains from the databases. Based on the principle of similarity search (BLASTn search), individual strains were identified down to the species level by utilizing the validated Online Dermatophyte Database of the Westerdijk Fungal Biodiversity Institute (formerly Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures CBS), Utrecht, The Netherlands (www.westerdijkinstitute.nl). In addition, we compared sequences of our samples with those contained in the very comprehensive database of the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) in Bethesda, Maryland, USA.

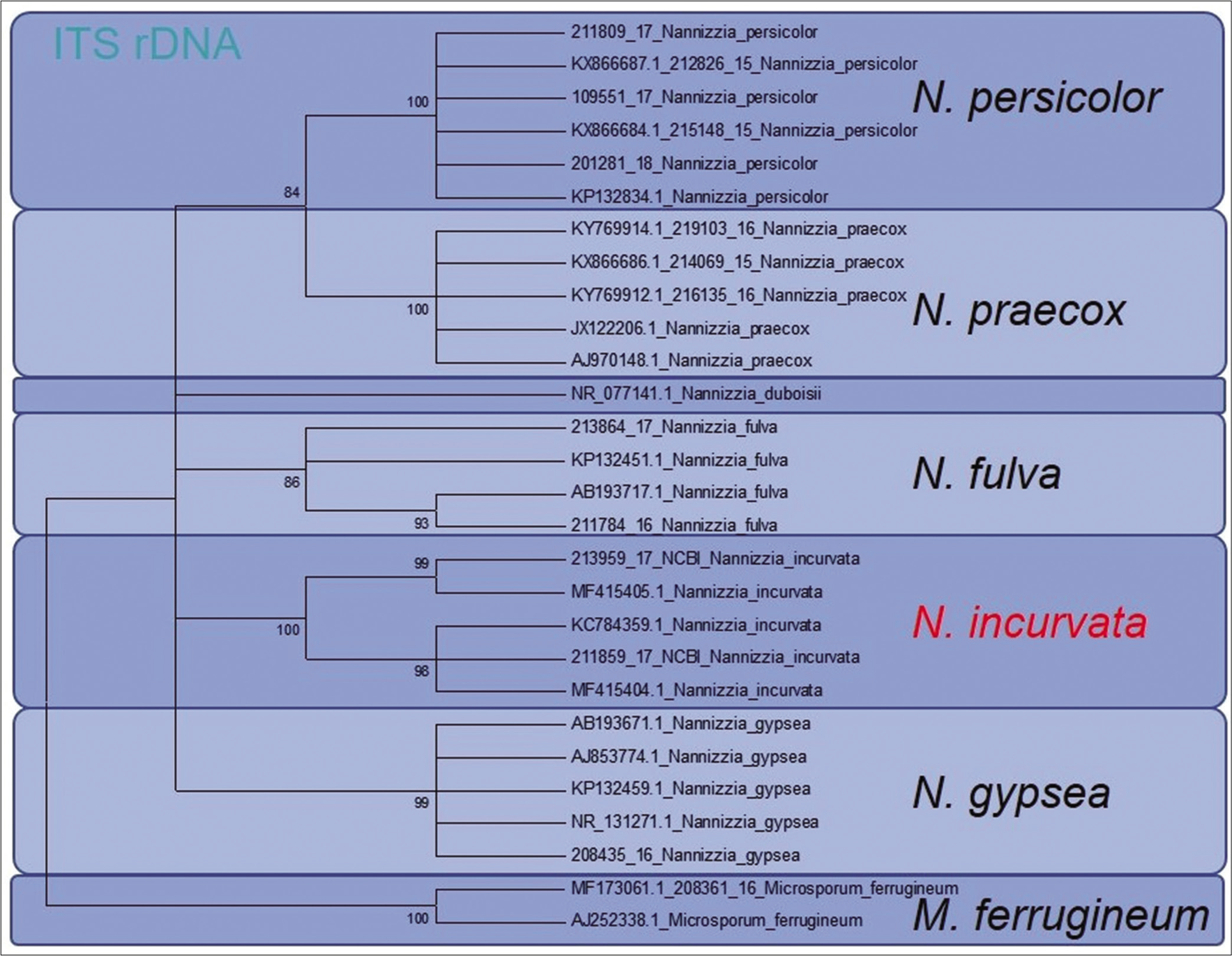

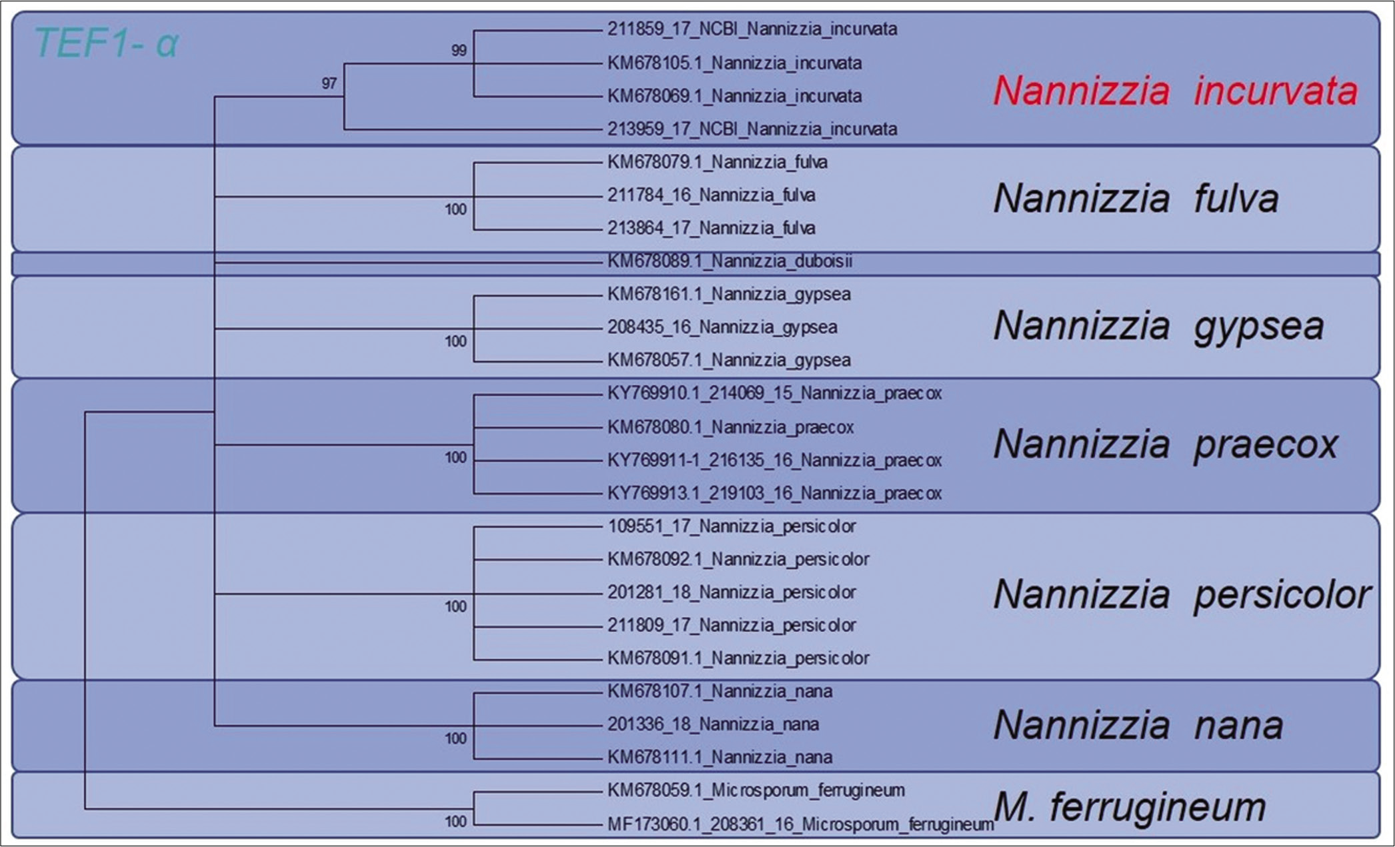

In the ITS region, 100% accordance was found with the reference sequence of N. incurvata deposited at the Database of the NCBI under the Accession number MF415405 and MF415404, respectively. For the TEF 1 α gene, the sequence KM678069 of N. incurvata is available. Due to several revisions of previously submitted sequences, this sequence, however, is deposited under the wrong species name N. gypsea. The phylogenetic analysis of the strains based on ITS region of the rDNA and of the TEF 1 α-gene in a dendrogram allows genetic differentiation between N. incurvata and the close related species N. gypsea and N. fulvum [Figure 3a and b].

- Phylogenetic analysis of both reported patients isolated Nannizzia incurvata strains. Based on ITS region of the rDNA, the dendrogram showed clear genetic differentiation between Nannizzia incurvata and the closely related species Nannizzia gypsea and Nannizzia fulva

- Phylogenetic analysis of both reported patients isolated Nannizzia incurvata strains. Sequencing of the translation elongation factor 1 α-gene allowed clear phylogenetic distinction between Nannizzia incurvata strains and the closely related species N. gypsea and Nannizzia fulva

Deposition of the isolates in strain collections and gene databases

Both ITS and TEF1 α gene sequences of the two strains are deposited at the NCBI database, the ISHAM-ITS-Database and at the “Fungal MLST Database.” The strains were deposited at the German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures (DSMZ, Braunschweig, Germany).

NCBI deposition: ITS region N. incurvata strain 213959/2017 (patient 1)—NCBI accession number MF 415405.1. ITS region N. incurvata strain 211859/2017 (patient 2)—NCBI accession number MF415404.1.

Deposition at the culture collection DSMZ in Braunschweig, Germany: N. incurvata strain 213959/2017 (patient 1)— DSM106637. N. incurvata strain 211859/2017 (patient 2)— DSM106636.

Sequencing of the TEF1-α gene: For strain 213959/2017, no cluster to compare was available. Strain 211859/2017 clustered with KM678105.1 from the NCBI database. Note: Due to the new taxonomy and nomenclature change, KM678105.1 was first assigned as N. gypsea, but has to be considered now as N. incurvata.

Discussion

Taxonomy of Nannizzia incurvata

N. incurvata represents a rare geophilic dermatophyte, here isolated from two patients from Vietnam and Cambodia. N. incurvata was first described in 1961 by Stockdale, at that time under the species name M.incurvatum.6 In 1963, N. incurvata was referred as belonging to the so called N. gypsea (formerly M. gypseum) complex, which included besides N. gypsea (formerly M. gypseum) the other morphologically closely related geophilic species N. fulva (formerly M. fulvum) and N. incurvata.7,8

Now, according to the new taxonomy, the genus Nannizzia has 10 species: N. aenygmaticum, N. corniculata, N. duboisii,N. fulva,N. gypsea,N. incurvata,N. nana,N. persicolor,N. praecox and N. perplicata.1,9

According to the recently published molecular-based new taxonomy of dermatophytes, N. incurvata is considered as a separate geophilic species within the clade C: Nannizzia. Although rare, or underdiagnosed, this dermatophyte can also cause human infections.1 This is the first isolation of N. incurvata in Cambodia, and the first description of favus in a child due to this dermatophyte.

Morphologic features of Nannizzia incurvata

Colonies of the dermatophytes belonging to the genus Nannizzia are described in the review of De Hoog et al. as mostly cottony to powdery, whitish to brown, with a cream-colored, brown or red pigmentation of the surface.1 Hyphae are thin-walled and hyaline. Sexual states of Nannizzia were described, after mating, like with Arthroderma genus.10,11 First impression of the fast-growing dermatophyte N. incurvata on Sabouraud's dextrose agar is that the bright brown to cinnamon brown stained granular to powdery appearing colonies resemble the species N. gypsea. Morphologically, it is difficult or even impossible to differentiate N. gypsea from N. incurvata. The reverse side of the colonies was yellowish bright brown, but also a reddish yellow to wine red staining is possible. The history of a journey to or living in Southeast Asia, in particular, the region of Vietnam and neighboring countries, should be a reason to look more deeper for this species, not the least to use molecular methods of sequencing for exact species identification. Microscopically, clavate, thin-walled sessile microconidia located alongside hyphae are seen [Figure 2 d].2 Macroconidia are described as abundant, echinulate, thick-walled, ellipsoid, (3-) 4-6(-9)- and septate, 8–12 × 30–50 μm [Figure 2 c].

Geographic distribution of dermatophytoses due to Nannizzia incurvata

Infections due to the ubiquitous dermatophyte N. gypsea occur worldwide. Tinea capitis and tinea corporis due to N. gypsea are common and were reported from a multitude of countries.12,13 In Sri Lanka, N. gypsea was the commonest fungus isolated from children.14 Contrary to that, dermatophytoses due to N. incurvata are rarely reported; they were described in a few distinct countries only. The latest report originated from Southeast Asia, Vietnam.15 In Taiwan, N. incurvata was found to be cause of cat favus in four animals.16 In Brazil, in 692 soil samples, the formerly two teleomorphic species of M. gypseum (Arthroderma [A.] gypseum and A. incurvatum) were isolated in approximately 19% samples.17 The enzymatic activities (expression of keratinase and elastase) of these geophilic dermatophytes may play an important role in the pathogenicity and underlines the probable adaptation of this fungus to the animal parasitism. Using the phenotypical and molecular analysis, Microsporum identification and their teleomorphic states will provide a useful and reliable identification system.

In 2012, N. incurvata was isolated from a Sri Lankan child residing in Japan and suffering from favus.18 Other countries, where N. incurvata was described in the past, were the US,19 Japan20-23 and France.24 Rezaei-Matehkolaei et al.25 reported a 4-year-old Iranian boy who developed erythematous, itchy and annular lesion on his face. The etiological agent was M. gypseum identified based on its morphologic features. However, ITS sequencing of the DNA revealed that the isolate showed 98% homology to M. incurvatum strain CBS 172.64 (re-classified as N. incurvata). Recently, tinea corporis presenting as disseminated verrucous plaques caused by A.incurvatum (re-classified as N. incurvata) in a young Indian boy was published.26

Molecular identification of Nannizzia incurvata by sequencing of the rDNA

Garcia et al. from Brazil found that several dermatophyte species have a full-length PRP8 intein with a homing endonuclease belonging to the family LAGLIDADG, which is a powerful additional tool for identifying and classifying dermatophytes.27 Phylogenetically confirmed Epidermophyton floccosum was in the same clade as the Arthroderma gypseum complex, M. audouinii was close to M. canis, which allowed differentiating A. gypseum (N. gypsea) from A.incurvatum.

Here, sequencing of the ITS1-region of the rDNA enabled a clear distinction between N. incurvata and the other closely related Nannizzia species N. gypsea and N. fulva, but also N. praecox and N. persicolor [Figure 3a]. The same was found by sequencing the TEF 1 α gene [Figure 3b].

Acknowledgment

We thank Esther Klonowski, biologist from Leipzig, Germany, for the excellent support in preparing and formatting the manuscript. The scientific photographer Uwe Schossig, Leipzig, Germany, has made the excellent pictures of fungal cultures.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patients have given their consent for their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Toward a novel multilocus phylogenetic taxonomy for the dermatophytes. Mycopathologia. 2017;182:5-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The ultimate benchtool für diagnostics In: Atlas of Clinical Fungi, 4th Online Edition, Version 1.4.1. Utrecht, The Netherlands: Centraalbureau Voor Schimmelcultures, Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Reus, Spain. 2018.

- [Google Scholar]

- Translation elongation factor 1-α gene as a potential taxonomic and identification marker in dermatophytes. Med Mycol. 2015;53:215-24.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedgehog fungi in a dermatological office in Munich: Case reports and review. Hautarzt. 2018;69:576-85.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molecular epidemiology of Trichophyton quinckeanum-A zoophilic dermatophyte on the rise. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:21-32.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nannizzia incurvata gen. nov. sp. nov., a perfect state of Microsporum gypseum (Bodin) Guiart et Grigorakis. Sabouraudia. 1961;1:41-8.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The Microsporum gypseum complex (Nannizzia incurvata Stockd. N. gypsea (Nann.) comb. Nov. N. fulva sp. nov.) Sabouraudia. 1963;3:114-26.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Variation in the Microsporum gypseum complex. II. A genetic study of spontaneous mutation in Nannizzia incurvata. Mycologia. 1966;58:570-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A novel dermatophyte relative, Nannizzia perplicata sp. Nov. isolated from a case of tinea corporis in the United Kingdom. Med Mycol 2018 Oct 16 [Epub ahead of print]

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parthenogenetic production of fertile cleistothecia in Nannizzia incurvata Stockd. Under the influence of Chrysosporium species. Mycopathol Mycol Appl. 1969;37:193-214.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studies on the sexuality of Nannizzia. II. Morphogenesis of gametangia in N. incurvata. Mycologia. 1969;61:593-605.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinea circinata manus due to Microsporum gypseum in a HIV-positive boy in Uganda, East Africa. Mycoses. 2007;50:153-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human infections with Microsporum gypseum complex (Nannizzia gypsea) in Slovenia. Mycopathologia. 2017;182:1069-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fungal skin infections in a paediatric dermatology clinic. Ceylon Med J. 1993;38:75-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Distribution of species of dermatophyte among patients at a dermatology centre of Nghean province, Vietnam, 2015-2016. Mycopathologia. 2017;182:1061-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cat favus caused by Microsporum incurvatum comb. Nov. The clinical and histopathological features and molecular phylogeny. Med Mycol. 2014;52:276-84.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isolation of Microsporum gypseum in soil samples from different geographical regions of brazil, evaluation of the extracellular proteolytic enzymes activities (keratinase and elastase) and molecular sequencing of selected strains. Braz J Microbiol. 2012;43:895-902.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerion celsi due to Arthroderma incurvatum infection in a Sri Lankan child: Species identification and analysis of area-dependent genetic polymorphism. Med Mycol. 2012;50:690-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nannizzia incurvata infection of vellus hair. Br J Dermatol. 1971;85:582-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distribution of mating types among clinical isolates of the Microsporum gypseum complex. Mycopathologia. 1982;77:31-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phylogeny of Nannizzia incurvata, N. gypsea. N. fulva and N. otae by restriction enzyme analysis of mitochondrial DNA. Mycopathologia. 1990;112:173-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phylogenetic relationships of the genera Arthroderma and Nannizzia inferred from mitochondrial DNA analysis. Mycopathologia. 1992;118:95-102.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermatophytes from animals. Nihon Ishinkin Gakkai Zasshi. 2000;41:1-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Microsporum gypseum complex in man and animals. J Med Vet Mycol. 1992;30:301-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermatophytosis due to Microsporum incurvatum: Notification and identification of a neglected pathogenic species. Mycopathologia. 2016;181:107-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinea corporis presenting as disseminated verrucous plaques caused by Arthroderma incurvatum in a young Indian boy. Australas J Dermatol. 2017;58:e265-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinea capitis by Microsporum gypseum, an infrequent species. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2018;116:e296-9.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]