Translate this page into:

Oral ulcers in heart transplant patient

Correspondence Address:

Sergi Planas-Ciudad

Department of Dermatology, Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau, Sant Antoni Maria Claret 16708025 Barcelona

Spain

| How to cite this article: Planas-Ciudad S, Rozas-Muñoz E, Sánchez-Martínez M&, Puig L. Oral ulcers in heart transplant patient. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2018;84:750-752 |

History

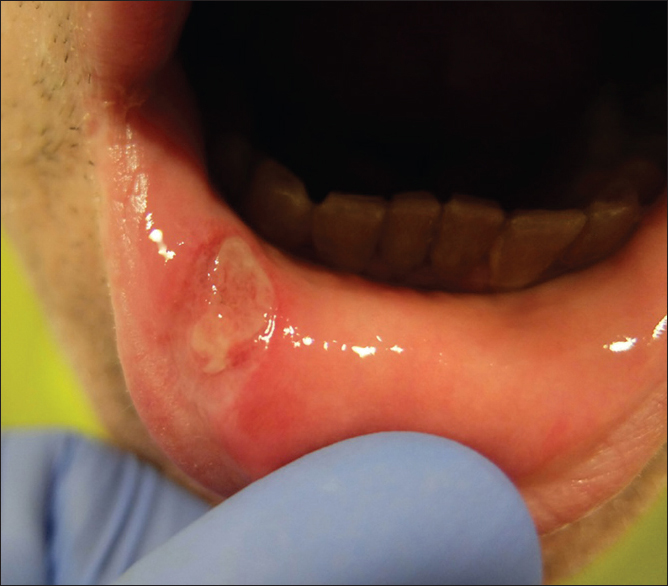

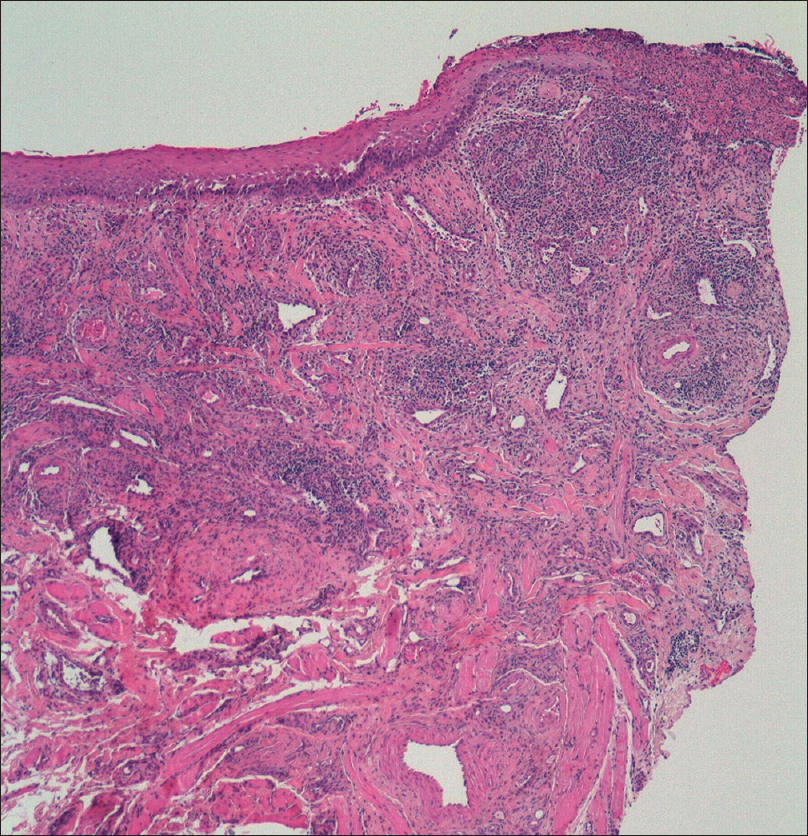

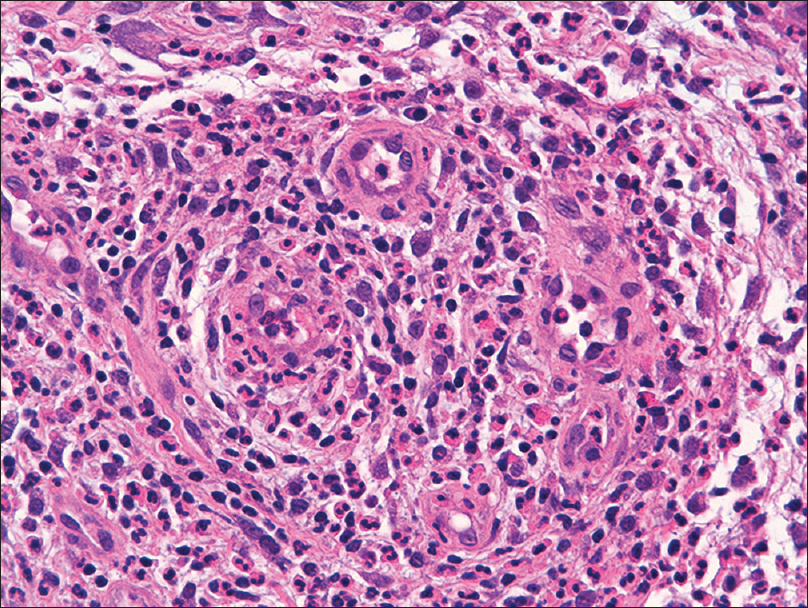

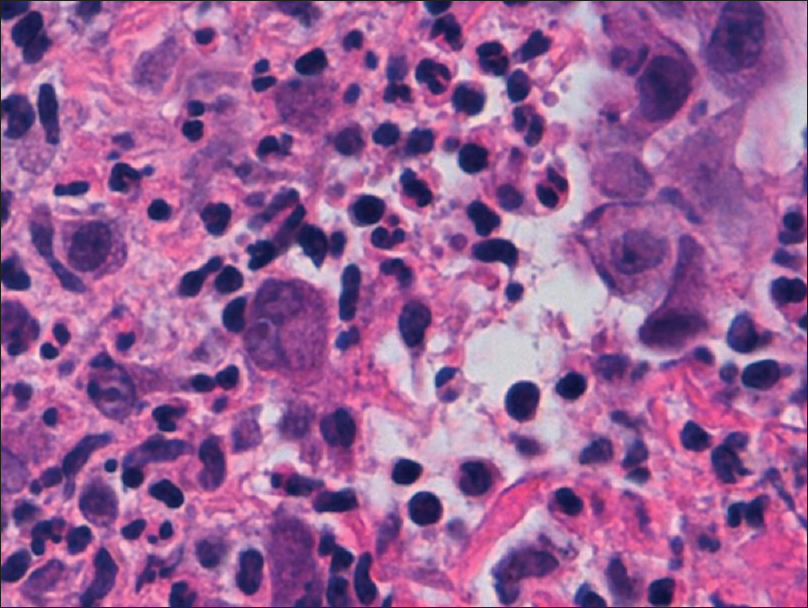

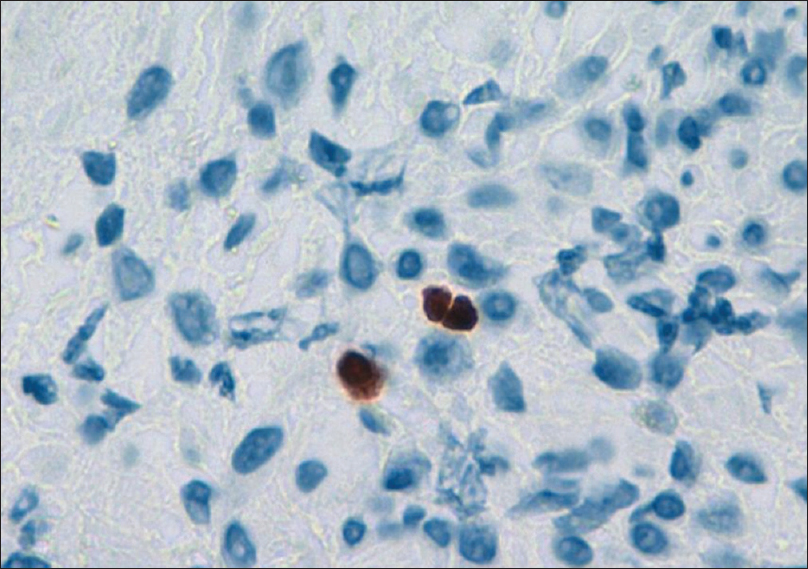

A 40-year-old man, with a history of heart transplantation two years back, presented with painful oral ulcers of three-weeks duration. Physical examination disclosed two large and deep, irregularly shaped ulcers on his lower lip and right buccal mucosa [Figure - 1]. No fever or other systemic symptoms were observed. His usual medications included mycophenolate mofetil 360 mg daily and tacrolimus 8 mg daily. Culture specimens were negative for bacteria and herpes simplex virus type I and II. Blood cell counts only showed a mild leukopenia (3.23 × 109/L; normal value: 3.80–11.00 × 109/L) and neutropenia (1.17 × 109/L; normal value: 1.80–7.00 × 109/L); the rest of the analysis were normal. Skin biopsy revealed a dense perivascular and mixed interstitial infiltrate composed of neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells [Figure - 2] and [Figure - 3]. Endothelial cells demonstrated large eosinophilic inclusions, mostly intranuclear and occasionally intracytoplasmic, with some of them showing an “owl's eye” appearance [Figure - 4].

|

| Figure 1: Deep, irregularly shaped ulcer on the lower lip |

|

| Figure 2: Ulcer with a dense perivascular and mixed interstitial infiltrate of neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells in the dermis. (H and E, ×400) |

|

| Figure 3: Enlarged endothelial cells with a dense perivascular infiltrate composed of neutrophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, and plasma cells. (H and E, ×200) |

|

| Figure 4: Some of the endothelial cells show large and eosinophilic nuclei which resemble an �owl's eye� (H and E, ×400) |

What is Your Diagnosis?

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) oral ulcers.

Answer

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) oral ulcers.

Discussion

CMV is a common opportunistic infection that usually affects immunocompromised patients, particularly those with human immunodeficiency virus infection, hematological malignant neoplasms, and solid-organ or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation recipients.[1],[2] Transmission may occur by body fluids, pregnancy, breastfeeding, blood transfusions, or after solid organ transplantation.[1],[2]

This virus may produce a wide range of diseases including pneumonitis, meningitis, retinitis, hepatitis, esophagitis, colitis, and mucocutaneous diseases. Mucocutaneous manifestations are varied and include oral and cutaneous ulcers, cutaneous nodules, maculopapular and urticarial eruptions, necrotic papules, verrucous plaques, pustules, and localized sclerodermoid changes.[3]

Oral ulcers secondary to cytomegalovirus infection are uncommon; but, they should be considered in any immunosuppressed patient with nonhealing ulcers, as its recognition may represent the first sign of systemic disease.[3] Clinically, they present as solitary or multiple, nonhealing ulcers of variable size and location.[2],[4] These nonspecific clinical features can overlap with several other causes of oral ulcers such as bacterial infections, herpes simplex I and II, drugs, trauma, and neoplasms, making specific investigations a very important aspect of diagnosis.[2]

Several laboratory tests are available but not all of them are useful for the diagnosis of mucocutaneous disease. Serologic tests determine immunity to the virus; but have no value for the diagnosis of active disease. Antigenemia [detection of viral proteins (pp65) in peripheral blood leukocytes] and quantitative deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) determinations in blood or plasma by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) may be useful for the diagnosis of visceral involvement, however, low or negative results may be seen in patients with focal disease. A positive culture from tissue biopsy can support the diagnosis,[4],[5] although slow growth of the virus and its low sensitivity limits its use.

Histopathological examination of the lesions is considered the gold standard for diagnosis.[2],[4],[5] Tissue invasion is indicated by swollen, vascular endothelial cells with enlarged nuclei, prominent nucleoli, and intranuclear and intracytoplasmic eosinophilic inclusions that resemble an “owl's eye.”[2] However, the sensitivity of histopathological examination is usually low as the cytopathological changes of cytomegalovirus infection are typically present only in scattered cells. Sensitivity can be improved in these cases by virus-specific immunohistochemistry staining.[2],[4],[5] In our case, PCR and culture specimens were taken from the ulcers; however, all the results were negative and the diagnosis was confirmed by immunoperoxidase staining with monoclonal anti-cytomegalovirus antibodies of the biopsy specimen [Figure - 5].

|

| Figure 5: Positive immunoperoxidase staining of cytomegalovirus |

At present, ganciclovir is considered the primary treatment of this infection.[1],[2] In case of drug resistance, foscarnet and cidofovir may be good alternatives.[1] Our patient was initiated on oral ganciclovir 450 mg daily with rapid improvement and subsequent resolution of the oral ulcers within one month [Figure - 6]. CMV prophylaxis was not initiated and mycophenolate mofetil was not discontinued. Monitoring was done weekly, by quantitative DNA estimation, during the first month and every 4 weeks during the next 6 months.

|

| Figure 6: Posttreatment ulcer on the lower lip |

We report an unusual case of cytomegalovirus oral infection in a patient with heart transplantation. Although the clinical appearance is nonspecific, cytomegalovirus infection should be considered in the differential diagnosis of oral ulcers in these patients, to establish a prompt diagnosis and treatment.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Prasad N, Jain M, Gupta A, Sharma RK, Agarwal V. An unusual case of CMV cutaneous ulcers in a renal transplant recipient and review of literature. NDT Plus 2010;3:379-82.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Mainville GN, Marsh WL, Allen CM. Oral ulceration associated with concurrent herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, and Epstein-Barr virus infection in an immunocompromised patient. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2015;119:e306-14.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Moscarelli L, Zanazzi M, Rosso G, Farsetti S, Caroti L, Annunziata F, et al. Can skin be the first site of CMV involvement preceding a systematic infection in a renal transplant recipient? NDT Plus 2011;4:53-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Epstein JB, Sherlock CH, Wolber RA. Oral manifestations of cytomegalovirus infection. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol 1993;75:443-51.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Razonable RR, Hayden RT. Clinical utility of viral load in management of cytomegalovirus infection after solid organ transplantation. Clin Microbiol Rev 2013;26:703-27.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

4,166

PDF downloads

1,612