Translate this page into:

Outcome of COVID-19 in patients with autoimmune bullous diseases

Corresponding author: Dr. Dipankar De, Department of Dermatology Venereology & Leprology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research (PGIMER), Chandigarh, India. dr_dipankar_de@yahoo.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: De D, Ashraf R, Mehta H, Handa S, Mahajan R. Outcome of COVID-19 in patients with autoimmune bullous diseases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2023;89:862-6.

Abstract

Background

Data on outcomes of Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) infection in autoimmune bullous diseases (AIBDs) patients is scarce.

Materials and methods

This single-centre survey-based-observational study included patients registered in the AIBD clinic of the Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India. All registered patients were contacted over telephone between June and October 2021. A survey was conducted after obtaining informed consent.

Results

Among 1389 registered patients, 409 completed the survey. Two hundred and twenty-two (55.3%) patients were females and 187 (45.7%) were males. The mean age was 48.52 ± 14.98 years. Active disease was reported by 34% patients. The frequency of COVID-19 infection in responders was 12.2% (50/409), with a case-fatality ratio of 18% (9/50). Rituximab infusion after the onset of pandemic significantly increased the risk of COVID-19 infection. Active AIBD and concomitant comorbidities were significantly associated with COVID-19 related death.

Limitation

Relative risk of COVID-19 infection and complications among AIBD patients could not be estimated due to lack of control group. The incidence of COVID-19 in AIBD could not be determined due to lack of denominator (source population) data. Other limitations include telephonic nature of the survey and lack of COVID-19 strain identification.

Conclusion

Use of rituximab is associated with higher probability of COVID-19 infection, while advanced age, active disease and presence of comorbidities may increase the risk of COVID-19 mortality in AIBD patients.

Keywords

Autoimmune bullous disease

COVID-19

pemphigus

bullous diseases

rituximab

Plain Language Summary

It is unknown whether COVID-19 infection outcomes differ in AIBD patients compared to the general population. In this survey-based study, we enquired about the outcomes of COVID-19 infections from patients registered in our AIBD clinic at a tertiary care centre in Northern India. All registered patients were contacted between June and October 2021. Out of 1389 registered patients, 409 completed the survey. Patients who received rituximab after the onset of pandemic were at higher risk of acquiring COVID-19 infection. Patients with advanced age, active disease and concomitant comorbidities were at higher risk COVID-19 related mortality.

Introduction

As severe COVID-19 indicates a hyper-inflammatory state, there is concern that the presence of pre-existing autoimmune disease or the use of immunosuppressants may increase the risk of severe COVID-19 infection.1 AIBD, especially pemphigus vulgaris and bullous pemphigoid, are potentially life-threatening. The management of AIBD is exigent and often needs the administration of high-dose systemic corticosteroids and other immunosuppressants.2 Optimisation of AIBD treatment during the COVID-19 pandemic requires clinicians to identify factors associated with poorer disease outcomes in COVID-19-positive AIBD patients and to understand whether these treatment modalities impact the overall prognosis of COVID-19 infection.

This telephonic survey was aimed to determine the impact of AIBDs on the susceptibility and outcome of COVID-19 infection.

Materials and Methods

Setting

This single-centre survey-based observational study was conducted on patients already registered in the AIBD clinic of the Department of Dermatology, Venereology & Leprology, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh. The study was initiated after obtaining approval from the Institutional Ethics Committee (intramural).

Methodology

All patients registered with our AIBD clinic were telephonically interviewed between June and October 2021. After obtaining informed consent (verbal initially, followed by filling out an e-consent form using Google-forms application), the patients were asked survey questions. Clinico-demographic parameters such as age, sex, diagnosis, duration of illness, comorbidities and habits of smoking or alcohol consumption were obtained from their clinical records. Other parameters, such as course and status of AIBD at the time of survey and current treatment regimens, as well as history pertaining to COVID-19 infection, were sought over a telephone conversation. We considered the number of patients with AIBD acquiring COVID-19 infection, frequency of complicated COVID-19 infections in AIBD patients, and frequency of flare/relapse episodes of AIBD during active COVID-19 infection as our outcome measures. Clinical details of patients who died due to COVID-19 infection were collected by reviewing their medical records and through history obtained from family members.

Statistical methods

Clinico-demographic characteristics and COVID-19 outcomes of the study population were summarized by descriptive statistics. Quantitative variables have been presented as mean, median (interquartile range, IQR), and count (percentage) as applicable. Logistic regression was used to estimate associations with adjustments for potential confounders. We considered α = 0.05 as statistically significant.

Results

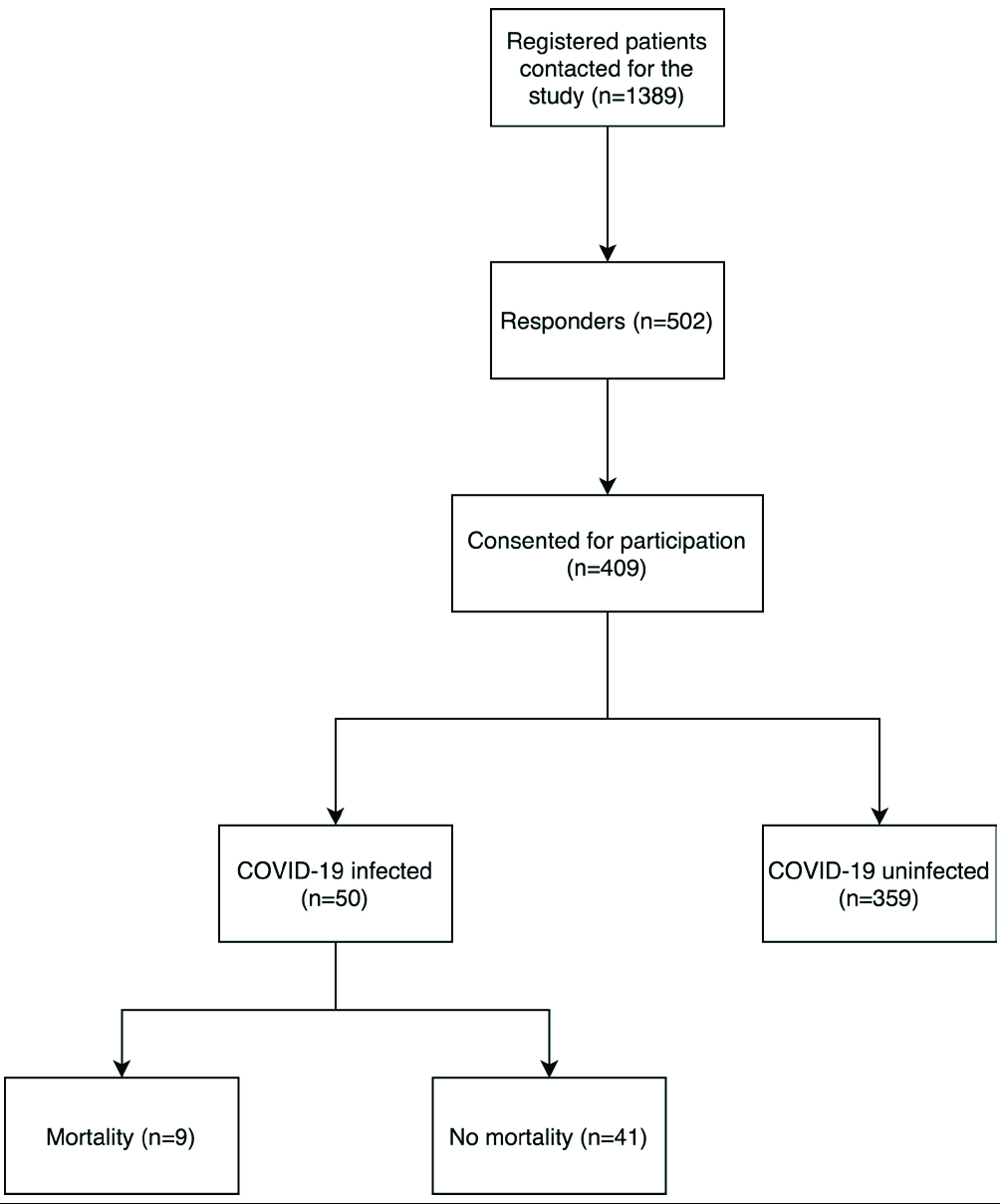

We attempted to contact all patients registered with our AIBD clinic telephonically (n = 502). Among them, 42 patients refused to answer our survey as they were in remission off therapy for a long duration; 19 patients refused informed consent, and 32 patients had died of various causes prior to the onset of pandemic. The remaining 409 patients or their attendants answered our survey [Figure 1]. We failed to contact the other patients due to incorrect phone numbers in their clinic files, or they failed to answer our calls (at least twice, on 2 different days).

- Number of patients at each step

Study participants

Among 409 responders, 222 (55.3%) patients were females and 187 (45.7%) were males. The mean age was 48.52 ± 14.98 years. The most frequent diagnoses were pemphigus vulgaris [281 (68.7%)], pemphigus foliaceous [19 (4.6%)], or bullous pemphigoid [33 (8.1%)]. Active disease at the time of answering the survey was reported by 34% patients. Eighty patients (19.5%) had received rituximab prior pandemic, while 220 (53.8%) patients received immunosuppression such as oral steroids/prednisolone or other steroid-sparing agents, including rituximab [30 (7.33%)] during the COVID-19 pandemic. Table 1 summarises the clinicodemographic profile of study participants.

| Parameter | Observed value | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD), in years | 48.52 ± 14.98 (5–89) | |

| Gender | Males | 187 (45.7%) |

| Females | 222 (55.3%) | |

| History of regular alcohol intake | 59 (14.4%) | |

| History of smoking | 24 (5.8%) | |

| Comorbidities present | 141 (34.5%) | |

| Total number of comorbidities (n = 145) | Diabetes mellitus | 58 |

| Hypertension | 79 | |

| Coronary artery disease | 13 | |

| Thyroid disease | 33 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 3 | |

| Active lung tuberculosis | 1 | |

| Known lung disease except TB | 3 | |

| Autoimmune disorder | 3 | |

| Chronic liver disease | 5 | |

| Diagnosis | Intraepidermal | 302 (73.8%) |

| Subepidermal | 107 (26.1%) | |

| AIBD disease status after onset of COVID-19 outbreak in India | Active and progressive | 38 (9.3%) |

| Active but non-progressive | 66 (16.1%) | |

| In remission—on therapy | 109 (26.7%) | |

| In remission—off therapy | 161 (39.4%) | |

| Relapsing and remitting | 35 (8.6%) | |

| Active disease | Oral | 101 (24.6%) |

| Cutaneous | 85 (19.5%) | |

| Mucocutaneous | 45 (11%) | |

| Other mucosae | 14 (3.4%) | |

| Immunosuppressives/steroid sparing agents received prior to the pandemic (at any time during the course of disease, before March 2020) | Prednisolone | 338 (82.6%) |

| Azathioprine | 115 (28.1%) | |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 11 (2.6%) | |

| Cyclophosphamide | 41 (10%) | |

| Methotrexate | 19 (4.6) | |

| Rituximab | 80 (19.5) | |

| Omalizumab | 3 (0.7%) | |

| Antibiotics | 52 (12.7%) | |

| Immunosuppressives/steroid sparing agents received during the pandemic (between March 2020 and the time of survey) | Prednisolone | 208 (50.8%) |

| Azathioprine | 39 (9.5%) | |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 5 (1.2%) | |

| Cyclophosphamide | 18 (4.4%) | |

| Methotrexate | 9 (2.2%) | |

| Rituximab | 30 (7.3%) | |

| IVIg | 2 (0.48%) | |

| Antibiotics | 24 (5.9%) | |

| Immunosuppressives stopped during pandemic | Yes, by self without consultation | 39 (17%) |

| Yes, after consultation in at our clinic | 24 (10.5%) | |

| Yes, after consultation elsewhere | 17 (7.4%) | |

| No | 149 (65.1%) | |

| Tested positive for COVID-19 | Yes | 50 (12.2%)* |

| No | 359 (87.8%) | |

| Mode of testing for COVID-19 | Antigen testing | 3 (6%) |

| RT-PCR | 44 (88%) | |

| CT-scan | 2 (4%) | |

| Unaware of test used | 4 (8%) | |

| Suffered from symptoms of COVID-19 | Yes | 17 (34%) |

| No | 33 (66%) | |

| Effect on AIBD | No lesions of AIBD | 42 (84%) |

| Flare of AIBD | 6 (12%) | |

| Improvement of AIBD | 2 (4%) | |

| Medications for AIBD | Stopped | 14 (28%) |

| Continued, unaltered | 20 (40%) | |

| Unsure | 16 (32%) | |

| Suffered from complications of COVID-19 requiring hospitalisation | 17 (34%) | |

| Reason for hospitalisation | Breathlessness | 16 (32%) |

| Thrombosis | 1 (2%) | |

| Other organ dysfunction | 1 (2%) | |

| Unsure | 1 (2%) | |

| Required ICU admission | 13 (26%) | |

| Required oxygen supplementation | 17 (34%) | |

| Required assisted ventilation (other than intubation) | 9 (18%) | |

| Required intubation | 4 (8%) | |

| Death due to COVID-19 | 9 (18%) | |

AIBD: autoimmune bullous disorder, SD: standard deviation, TB: tuberculosis, COVID-19: coronavirus disease 2019, RT-PCR: reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction, CT scan: computed tomography scan, *data on viral variants (alpha, delta, omicron etc.) was not available

COVID-19 and its outcomes in AIBD patients

Fifty patients (12.2%, n = 409) tested positive for COVID-19 before the survey. Of them, 17 (34%) patients were symptomatic, while the remaining 33 (66%) were incidentally detected. Only six (12%) patients reported a flare of AIBD lesions. Among 50 patients with confirmed COVID-19 infection, 31 patients (62%) were on some form of immunosuppression during the pandemic, including 10 (20%) patients who had received rituximab during the pandemic (P < 0.05). The average time period between rituximab infusion and acquiring COVID-19 infection was 5.89 ± 6.01 weeks (1–20 weeks). On univariate analysis, AIBD patients receiving rituximab were 4.2 times more likely to acquire COVID-19 infection as compared to those not receiving any immunosuppression [OR: 4.263 (1.681–10.812), P = 0.002]. A total of 17 (34%) patients were hospitalised, all requiring oxygen supplementation, while nine (18%) required assisted ventilation (other than intubation) and 4 (8.5%) required intubation.

Nine patients (18%, n = 50) who tested positive for COVID-19 died of its complications. Four of these patients were on immunosuppressive therapy at the time of infection, including two patients who had received rituximab (lag period of 29 days and 14 days after infusion). Seven patients had other comorbidities (including hypertension, diabetes, thyroid disorder, coronary artery disease and carcinoma cervix). Active disease status during the pandemic, older age and concomitant comorbidities significantly increased the risk of death due to COVID-19 [Table 2]. Table 3 summarises the clinical data of patients who died due to COVID-19-related complications.

| Parameter (no. of patients) | Mortality (n = 9) | No mortality (n = 41) | P-value (Fisher’s exact test) | Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD), in years | 67.44 ± 11.99 | 47.61 ± 13.77 | <0.001* | - | |

| Continued follow up during lockdown (n = 23) | 2 (22.2%) | 21 (51.2%) | 0.152 | 0.272 (0.50–1.470) | |

| Presence of comorbidity (n = 21) | 7 (77.7%) | 14 (34.1%) | 0.025 | 6.750 (1.235–36.908) | |

| Disease status during pandemic | Active and progressive (n = 5) | 3 (33.3%) | 2 (4.8%) | 0.042# | - |

| Active but non-progressive (n = 10) | 0 (0%) | 10 (24.3%) | |||

| In remission- on therapy (n = 11) | 1 (11.1%) | 10 (24.3%) | |||

| In remission- off therapy (n = 21) | 5 (55.5%) | 16 (39.0%) | |||

| Relapsing and remitting (n = 3) | 0 (0%) | 3 (7.3%) | |||

| Continued immunosuppression during the pandemic (n = 30) | 4 (44.4%) | 26 (63.4%) | 0.454 | 0.462 (0.107–1.988) | |

| Received rituximab during the pandemic (n = 9) | 2 (22.2%) | 7 (17.07%) | 0.657 | 0.721 (0.123–4.229) | |

*Mann-Whitney U test, #post-hoc analysis revealed a significant association of mortality with the active and progressive disease only (adjusted Z-score >1.6)

| Sr. No. | Age in years/sex | State | Diagnosis | Comorbidities | Alcohol/smoking | Immunosuppressives in the past | Immunosuppressives during pandemic | Disease status during the pandemic | The month of getting COVID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 80/M | Chandigarh | Pemphigus vulgaris | Diabetes mellitus, hypertension | No | Prednisolone, cyclophosphamide | None | Remission off therapy | December 2020 |

| 2 | 60/F | Haryana | Pemphigus vulgaris | Carcinoma cervix | No | Prednisolone, rituximab | None | Remission off therapy | October 2020 |

| 3 | 67/M | Chandigarh | Dermatitis herpetiformis | Coronary artery disease | No | Dapsone | None | Remission off therapy | April 2021 |

| 4 | 75/F | Punjab | Bullous pemphigoid | Diabetes mellitus, hypertension | No | None | None | Remission off therapy | March 2021 |

| 5 | 85/F | Chandigarh | Bullous pemphigoid | Hypothyroid, chronic kidney disease | No | Tetracycline | None | Remission off therapy | May 2021 |

| 6 | 65/F | Haryana | Bullous pemphigoid | Diabetes mellitus, hypertension | No | Prednisolone | Prednisolone | Active and progressive | December 2020 |

| 7 | 60/M | Haryana | Pemphigus vulgaris | Hypothyroidism | No | Prednisolone | Prednisolone | Remission on therapy | July 2020 |

| 8 | 45/M | Uttar Pradesh | Pemphigus vulgaris | None | Smoking | None | Prednisolone, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate and rituximab | Active and progressive | April 2021 |

| 9 | 70/M | Uttar Pradesh | Pemphigus vulgaris | None | Alcohol | None | Prednisolone, rituximab | Active and progressive | April 2021 |

Discussion

Data on COVID-19 outcomes among patients with AIBD is not robust. Such patients may be at an added risk of acquiring infection due to chronic disease courses, requirement of frequent travel to healthcare facilities, and immunosuppression for the management of their primary disease.

A recent systematic review including a pooled total of 732 AIBD patients documented COVID-19 symptoms in 70 patients (9.5%), while the diagnosis of COVID-19 was confirmed in 16 (2.1%) patients.3 Six (0.8%) patients developed severe symptoms requiring hospital admission and three patients (0.4%) died of COVID-19, all being elderly with/ without comorbidities.3 In our study, the frequency of confirmed COVID-19 infection (12.2%) and mortality (2.2%) were over five times higher. This may be attributed to the timing of our survey in October 2021, after the spread of the delta variant of COVID-19, which had higher transmissibility and mortality compared to the initial Alpha variant.4 ,5

The rate of infection with coronavirus in AIBD patients in our study was 12.2%, with a case-fatality ratio of 18%, compared to the incidence rate of 2.7% and case fatality ratio of 1.87% in the general population of our region (states of Punjab, Haryana, Himachal Pradesh and union territory of Chandigarh) during a similar time period (calculated as the total number of cases observed in these four states from March 2020 to 31st October 2021, divided by the total population of these states as per the last population census).6 Our data projects an unfavourable prognosis of COVID-19 in AIBD patients compared to normal population. Attributable risk could not be calculated due to the observational nature of the current study.

Advanced age, active disease during the lockdown, andpresence of comorbidities were significantly associated with death due to COVID-19 infection. Association of mortality with disease activity may be explained by a higher risk of exposure to infection due to frequent hospital visits and a higher likelihood of receiving immunosuppressants. Comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, obesity, reduced kidney function, and chronic liver disease are well-established risk-factors for death due toCOVID-19.7,8 Seven of nine patients who died in the present study had at least one comorbidity; while the remaining two patients received rituximab for the active disease.

Administration of rituximab after the onset of pandemic in India was significantly associated with COVID-19 infection in our study. Similar observations were made by Joly et al. who noted a more than five-fold higher incidence of COVID-19 infection in AIBD patients who received rituximab compared to those not receiving rituximab.9 Observational outcome statistics have been encouraging for several immunosuppressants, however, data pertaining to rituximab is not as reassuring.10 Worsened primary disease and mortality after COVID-19 infection in patients receiving rituximab have been documented in rheumatological diseases.11 ,12 The most plausible mechanism by which rituximab impacts COVID-19 outcomes is blunting of humoral immunity. A study by Anderson et al. observed that after adjusting for comorbidities and various other confounding factors, the use of most immunosuppressant drugs was not associated with increased mortality.13 Rituximab, whether used for autoimmune conditions or cancer, however, increased the risk of COVID-19 mortality.13 The association between rituximab treatment and adverse COVID-19 outcomes did not reach statistical significance in our study, likely due to the limited number of patients receiving rituximab and very low number of observed mortality. Two out of nine patients who died due to COVID-19-related complications had received rituximab for AIBD.

Rituximab has been advocated as the first-line treatment for pemphigus by several international guidelines and a recent surge in the availability of affordable biosimilars immensely increased its use.2 ,14 A safe approach to rituximab therapy for AIBD during the pandemic must be formulated.

Our study has some limitations. The relative risk of COVID-19 infection and complications among AIBD patients could not be estimated due to lack of a control group. The incidence of COVID-19 in AIBD could not be determined due to lack of denominator (source population) data.

Despite the ongoing pandemic for last two years, the formulation of evidence-based guidelines for the management of AIBD during the pandemic has been difficult due to the scarcity of data on COVID-19 outcomes in this population. This study has a clear relevance in this context as it is among the largest studies of COVID-19 in AIBD patients and is the only such study from the Indian subcontinent.

Conclusion

Use of rituximab increases the odds of acquiring COVID-19 infection, while advanced age, active disease status for AIBD, and presence of comorbidities may increase the risk of mortality due to COVID-19.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Abhay Gupta, Dr. Akshay Meena, Dr. Aman Goyal, Dr. Apoorva Sharma, Dr Kittu Malhi, Dr. Sophia Rao, Dr. Sukhdeep Singh, Dr. Anish Thind, Dr. Divya Garg, Dr. Janaani Pradmanabhan, Dr. Sukhmanjeet Singh, Dr. Dikshit Bhatta, Dr. Roshini Nagaraja, Dr. Seema Negi, Dr. Sejal Jain and Dr. Sweta Leena for their assistance in data collection.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- COVID-19: autoimmunity, multisystemic inflammation and autoimmune rheumatic patients. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2022;24:e13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Updated S2K guidelines on the management of pemphigus vulgaris and foliaceus initiated by the european academy of dermatology and venereology (EADV) J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:1900-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 outbreak and autoimmune bullous diseases: A systematic review of published cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:563-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- SARS-CoV-2 Delta VOC in Scotland: Demographics, risk of hospital admission, and vaccine effectiveness. Lancet. 2021;397:2461-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Hospital admission and emergency care attendance risk for SARS-CoV-2 delta (B.1.617.2) compared with alpha (B.1.1.7) variants of concern: A cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22:35-42.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical determinants for fatality of 44,672 patients with COVID-19. Crit Care. 2020;24:179.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584:430-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Incidence and severity of COVID-19 in patients with autoimmune blistering skin diseases: A nationwide study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:494-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical outcomes of COVID-19 in patients taking tumor necrosis factor inhibitors or methotrexate: A multicenter research network study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:70-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- COVID-19 outcomes in patients with inflammatory rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases treated with rituximab: A cohort study. Lancet Rheumatol. 2021;3:e419-26.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Factors associated with COVID-19-related death in people with rheumatic diseases: Results from the COVID-19 Global Rheumatology Alliance physician-reported registry. Ann Rheum Dis. 2021;80:930-42.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Long-term use of immunosuppressive medicines and in-hospital COVID-19 outcomes: A retrospective cohort study using data from the National COVID Cohort Collaborative. Lancet Rheumatol. 2022;4:e33-41.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- British Association of Dermatologists’ guidelines for the management of pemphigus vulgaris 2017. Br J Dermat. 2017;177:1170-201.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]