Translate this page into:

Patch tests in adverse cutaneous drug reaction

Correspondence Address:

C Balachandran

Department of Skin & S.T.D., Kasturba Medical College, Manipal-576119, Karnataka

India

| How to cite this article: Balachandran C, Shenoi SD, Sarkar D, Ravikumar B C. Patch tests in adverse cutaneous drug reaction. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2002;68:13-15 |

Abstract

Twenty-one patients with history of adverse cutaneous drug reaction were patch tested with 23 commonly used drugs in 5% concentration in petrolatum. Nine patients (42.85%) tested were positive to the incriminated drugs while 3 (14.28%) showed positive reactions to other drugs. Highest positivity (50%) was seen in maculo-popular cases while Stevens-Johnson syndrome and exfoliative dermatitis patients showed negative results.

Introduction

Drug reactions are a major setback in the treatment of any disease[1],[2] and constitute about 1-2% of all outpatients and 5-10% of all inpatients.[3],[4]

The diagnosis of a drug rash is purely clinical, based on the temporal correlation between drug intake and onset of symptoms and improvement after drug withdrawal. Not infrequently it becomes difficult to pin point the exact causative drug, especially with polypharmacy. The gold standard therefore remains oral provocation or re-challenge, but it is difficult, time consuming and unethical. Hence various tests have been developed for the diagnosis of drug reactions, ranging from prick test, intradermal tests to basophil degranulation tests. Patch testing is a widely used noninvasive test in the field of contact dermatitis. Although the reliability of patch testing in identification of the culprit drug has been reported, there is lack of a comprehensive study in this regard and there has been no prospective study determining the value and specificity of patch test in case of cutaneous drug reactions. Guidelines regarding the procedure are also lacking. This study was carried out in our department with 23 commonly used drugs in clinical practice to evaluate patch testing in identifying the culprit drugs in adverse cutaneous drug reactions (ACDR).

Materials and Methods

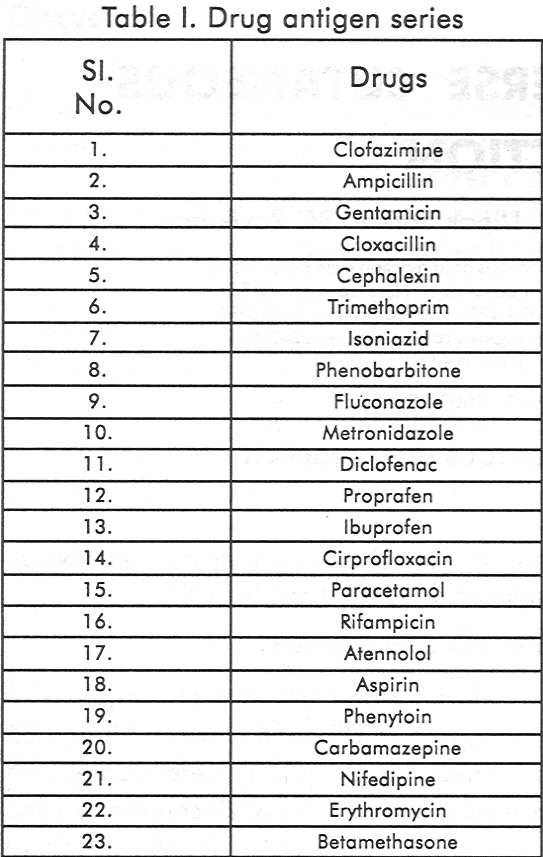

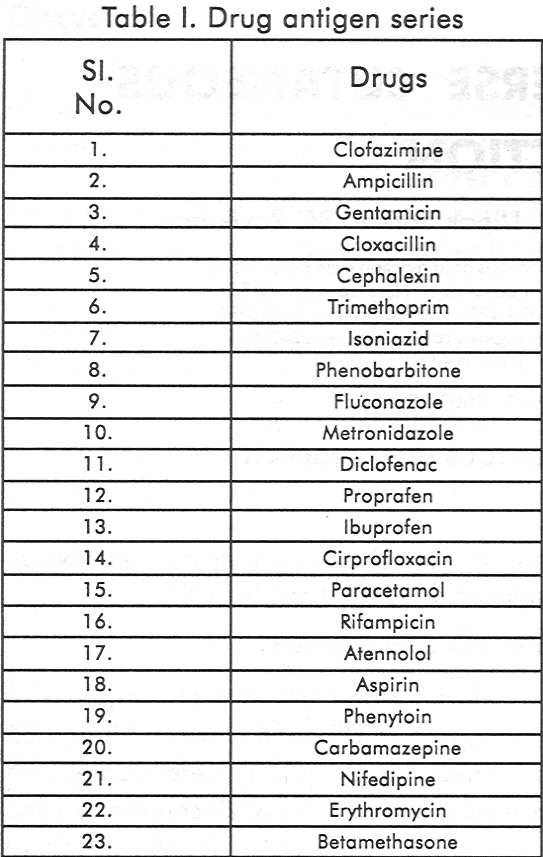

Twenty-one patients (11 males, 10 females), with ACDR aged between 19 and 65 years (mean 36.28 years) were studied. The analytical grade samples of 23 commonly used drugs were obtained from different pharmaceutical companies and antigens were prepared in white petrolatum in 1 % and 5% concentration.

Eight control subjects without history of ACDR were patch tested with the 23 drugs of both concentrations and as none showed irritant reactions, 5% concentration was chosen for the study. The drugs were stored in 5ml syringes in the refrigerator. All patients were patch tested with 23 antigens 1 month after subsidence of rash. None had lesions over the test site and none was on steroids or other immunosuppressives for 1 month prior to testing. Any suspected drug other than that present in the series was also tested in 5% concentration. The patches were removed after 48 hours and readings were taken after 30 minutes. A second reading was taken after 72 hours and graded as per the ICDRG recommendation. Statistical evaluation for the sensitivity and specificity of patch testing was done using standard statistical formulae.

Results

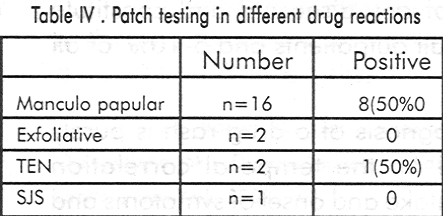

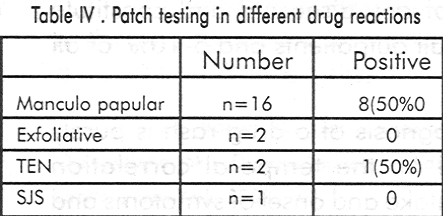

Out of 21 patients, 16 (76.19%) had maculopapular eruptions,2 (9.52%) had TEN, 2 (9.52%) exfoliative dermatitis and 1 patient (4.76%) had SJS.

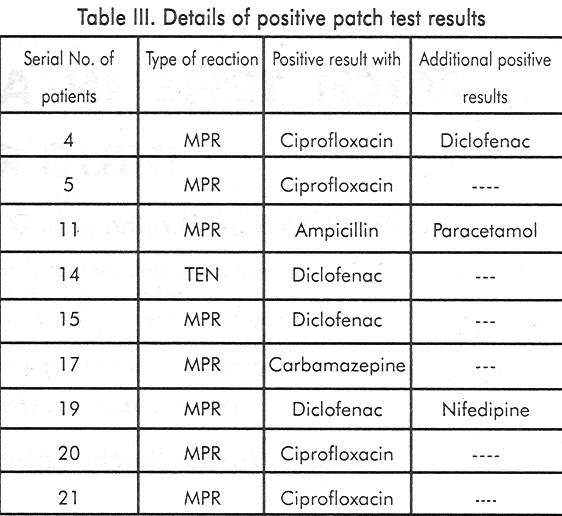

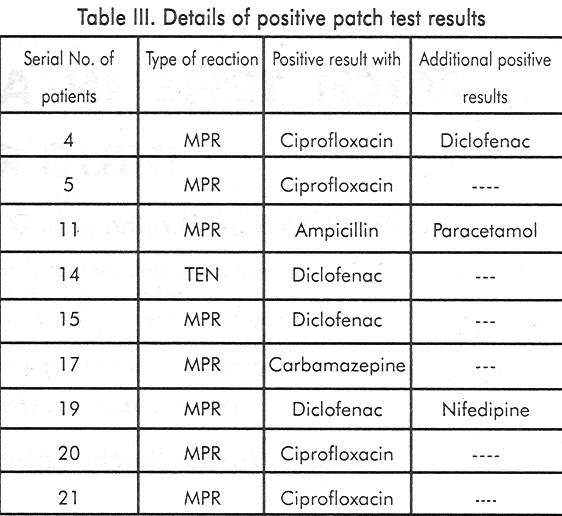

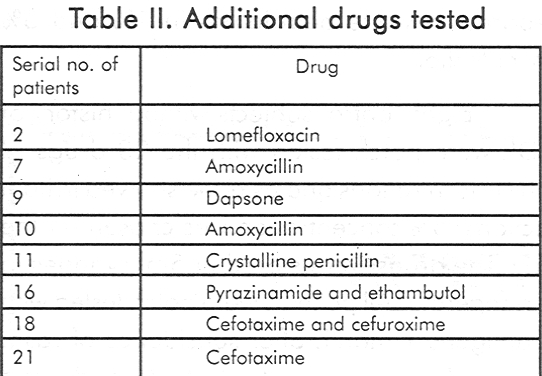

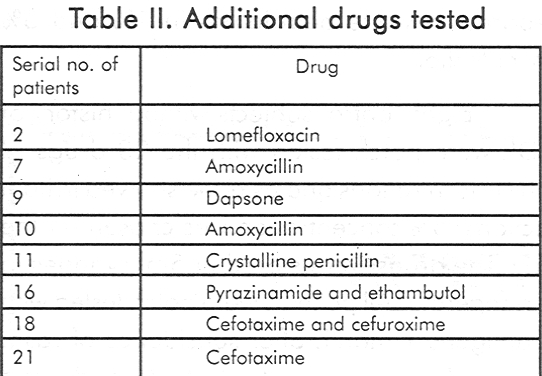

[Table - 1] shows the list of the 23 drugs in the series and [Table - 2] shows the additional drugs tested. Nine out of 21 (42.85%) tested positive to the incriminated drug while 3(14.28%) had positive reactions to others.

Details of positive patch test results are shown in [Table - 3]. The highest positivity of patch testing (50%) was seen in maculopapular type of drug rash while Stevens Johnson syndrome and exfoliative dermatitis patients showed negative results [Table - 4]. After appropriate statistical analysis the sensitivity and specificity of patch tests were found to be 42.85% and 72.72% respectively. In 75% a positive patch test indicated true positivity and in 40% a negative patch test indicated true negativity. None of our patients showed side effects of patch testing. 7 developed asymptomatic erythema at the site of clofazimine patch which lasted for 57 days and subsided without any treatment.

Discussion

The in vivo diagnostic tests for ACDR are oral rechallenge, intradermal test, prick test and patch test. Patch test has been traditionally used in the diagnosis of eczematous drug eruption and systemic contact dermatitis.

Type IV hypersensitivity has been implicated in drug reactions like erythema multiforme, toxic epidermal necrolysis, lichenoid reactions, lupus-like reactions and some morbilliform eruptions.[5] Since Alanko et al[6] first used patch testing for determining the causative drugs in fixed drug reaction, several authors have tried the test in different types of drug reactions with varied results.[7],[8]

In our series it was significant that 8 out of 16 (50%) maculo-popular cases showed positive patch test results. Barbaud et al[9] reported 59.3% positivity in the maculo-papular group. Different workers have used varying concentrations of the antigens ranging from 1-30%.[9],[10] However we used 5% concentration in our study. The sensitivity and specificity rate in the present study was 42.15% and 72.72% respectively. None reacted adversely to patch testing, except 7 patients who developed asymptomatic erythema over the clofazimine patch pigment due to vasodilation and not due to accumulation of lipofuschin pigment within the macrophages as it subsided within a week.

Prospective studies on larger number of patients need to be carried out to standardise the concentration of the drug, the vehicle for individual drug and the timing of reading.

| 1. |

De Swarte RD. Drug allergy -Problems and strategies. J All Clin Immunol 1984; 7: 209-221.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Jick H. Adverse drug reactions. The magnitude of the problem. J All Clin Immunol 1984; 74:555-557.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Shapiro S, Stone D, Siskind V. Drug rash with ampicillin and other penicillins.Lancet 1969; 2:969-972.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Arndt K, Jick H. Rates of cutaneous reactions to drugs. A report from Boston collaborative drugs surveillance program. JAMA 1976; 235:918-922.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Breathnach SM, Hintner H. Adverse Drug Reactions and the Skin. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, 1992;p.32

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Alanko K, Stubb S, Reitamo S. Topical Provocation of FDE. Br J Dermatol 1987; 116:561-567.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Vaillant L. Patch testing with carbamazepine reindudion of exfoliative dermatitis. Arch Dermatol 1989;125:299.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Houwerjil J, De Gast GC, Nater GP. Patch test in drug eruptions. Cant Derm 1975; 1: 180-192.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Barbaud A, Penetract SR, Trechot P, et al. Use of skin testing in the investigation of cutaneous adverse drug reactions. Br J Dermatol 1998;139:49-58.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Calkin JM, Maibach HI. Delayed hypersensitivity drug reactions diagnosed by patch testing. Cant Derm 1993;29:223-223.

[Google Scholar]

|