Translate this page into:

Role of cosmetic camouflage in improving quality of life in dermatological disorders: A narrative review

Corresponding author: Dr. Mala Bhalla, Department of Dermatology, Government Medical College and Hospital, Chandigarh, India. malabhalla@yahoo.co.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Arora A, Bhalla M. Role of cosmetic camouflage in improving quality of life in dermatological disorders: A narrative review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2025;91:196-203. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_1117_2023

Abstract

Camouflage is a system of techniques using cosmetics to conceal, diminish and disguise visible disfigurements of pigment or texture of skin mainly over visible areas. A wide variety of options are available which can be used as camouflage cosmetics. Over the years many authors have published studies highlighting the importance of camouflage in different dermatological disorders like pigmentary, vascular, scars, acne vulgaris and many more. In this review we present 15 such studies assessing QOL in patients of dermatological diseases who were given camouflage therapy. The evidence presented here gives us an insight into the positive effects of camouflage/cover up make up when offered to patients with different dermatological conditions.

Keywords

Cosmetic camouflage

quality of life

dermatological disorders.

Introduction

Skin, hair and nails are crucial organs of cosmetic importance and they form the medium of expression of one’s individuality. Flawless skin in today’s social media–driven lifestyle has become a goal for one and all. Even slight imperfections seem unacceptable and are a cause of concern for patients suffering from pigmentary disorders, vascular lesions or in fact any blemish on the visible parts of the body. The pursuit of flawlessness has become of utmost importance. The treatments for such disorders usually take time to show results, therefore the use of corrective make up to cover the lesions till they show a clinical response has been shown to improve the patient’s quality of life.

Camouflage, when simply described, is a system of techniques using cosmetics to conceal, diminish and disguise visible disfigurements of pigment or texture of skin mainly over visible areas. The main purpose is to help cope with the psychological effects by helping to normalise appearance and increase social acceptability. It was first introduced during World War II to help burn victims improve their appearance and then further integrated with medical management by Joyce Allsworth, who formed the British Association of Skin Camouflage.1-4

A wide variety of options are available which can be used as camouflage cosmetics. The features common to all are that they should be opaque, waterproof, provide a good colour match, easy to apply and have good adherence to skin allowing long wear. The formulations of the camouflage cosmetics include creams, creamy and alcohol-based liquids, sticks and roll-ons. They usually have higher pigment content and fillers, thereby making them more opaque and more efficacious than commonly used make up. Various companies provide commercially available camouflage cosmetics in multiple colours, common ones being Dermacolor, Microskin and Dermablend Cover Creme Foundation. Theories of colour correction following the colour wheel and contouring to match skin’s imperfections also need to be considered for providing a good camouflage of lesions.5,6

In order to help patients learn the subtleties of application of camouflage make up, the British Red Cross Society provides education services to patients in the United Kingdom free of cost in the Skin Camouflage clinic. These services are supplemented by Changing Faces which is a charity organisation providing trained practitioners of camouflage and teaching and providing patients with medical makeup free of charge. In the United States, state-licensed medically trained camouflage therapists are available, who not only have the knowledge to demonstrate but also educate patients on how to use make up correctly.1,7.8

Despite evidence of the ability of camouflage to improve the quality of life (QOL) in patients of facial disfigurement, dermatologists still do not practice it regularly for their patients. A cross-sectional study published by Sandhu et al. demonstrated that dermatology residents, although aware about camouflage, did not recommend it regularly and were not convinced of its role in clinical dermatology practice. The study highlighted the need to include camouflage awareness and training during residency to increase acceptability among dermatologists.9

In today’s social media–driven world, the impact of various dermatological diseases on the QOL is being increasingly recognized and studied. To keep up with changing patient needs, a shift towards supportive care is the need of the hour whereby dermatologists institute camouflage or corrective make up to patients with dermatological disorders along with treatments to improve their QOL. To support this change, we present this review of studies assessing QOL in patients of dermatological diseases who were given camouflage therapy.

Methods

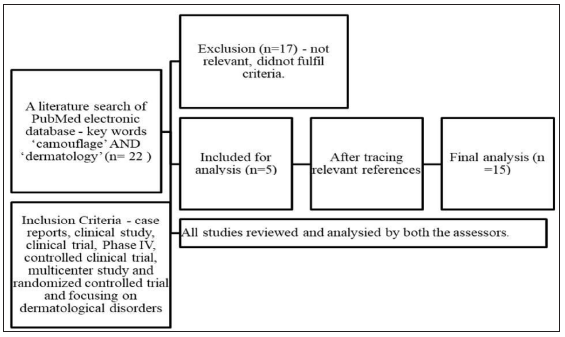

A literature search of PubMed electronic database was performed using key words ‘camouflage’and ‘dermatology’. A total of 22 search results appeared. Studies including case reports, clinical study, clinical trial, Phase IV, controlled clinical trial, multicentre study, and randomised controlled trial focusing on dermatological disorders have been included in this review. The studies that assessed QOL improvement by any of the multiple available tools were included. Only five relevant studies were found and abstracts of these were studied and reviewed by the two authors. The relevant references of the included articles were also traced and included, making a total of 15 case series and clinical trials. Studies focusing on QOL improvement in burn scars, post-radiation scarring, surgical scars, and head and neck cancers were not included in this review [Figure 1].

- Flow chart depicting the process of data collection and study analysis.

The objective of the review was to collate and analyse the evidence to suggest the impact of camouflage techniques on QOL improvement in various dermatological disorders using the available QOL indices.

Results

Study selection and overview

After literature research and cross-referencing, 15 studies10-24 were included, of which 9 studies included multiple indications. Only four studies focused on vitiligo, one on acne vulgaris and one on lupus erythematosus.13,14,16,22-24 Although all 15 were prospective studies, the control group was only present in 4 studies.14,16,22,23 The age groups included were varied in most studies with four studies focusing on the paediatric age group15,19-21 [Table 1].

| No. of studies | ||

|---|---|---|

| Total | 15 | |

| Indications studied | Vitiligo | 413,16,23,24 |

| Acne | 114 | |

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | 122 | |

| Multiple | 9 | |

| Type of study | Prospective studies | 15 |

| Control group present | 414,16,22,23 | |

| Duration of studies | Minimum | 2 weeks |

| Maximum | 24 weeks | |

| Mean | 7.6 weeks | |

| Age group studied | Adults | 9 |

| Paediatrics | 415,19,20,21 | |

| Both | 2 | |

| QOL questionnaire used | DLQI | 10 |

| cDLQI | 415,19,20,21 | |

| Other QOL questionnaires |

Skindex 1612 QOL perception without skin blemish12 WHOQOL 2614 fDLQI21 EuroQOL5D24 SF3624 |

|

| Disease specific |

SLE QOL22 VitiQOL24 |

|

| Psychological effect |

FNE12 Worry over skin disease12 Rosenberg self-esteem questionnaire22 Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale22 |

DLQI: Dermatology life quality index, FNE: Fear of negative evaluation, QOL: Quality of life, cDLQI: Children’s dermatology life quality index, fDLQI: Family dermatology life quality index, SLEQoL: Systemic lupus erythematosus – specific quality of life, HADS: Hospital anxiety and depression scale, EQ5D: EuroQol-5 dimension questionnaire, SF36: Short form health survey, ViTiQol: Vitiligo quality-of-life index.

Patient demographics

A total of 893 patients were recruited and data have been analysed for 775 patients. The demographic details of the patients, different diagnostic categories studied, and number of patients in these individual classes has been described in Table 2. Mean duration of disease was provided only in eight studies with minimum duration being 1.625 years and maximum being 18.8 years with a mean of 10.6 years.

| Total patients recruited | 893 | |

| Patients analysed | 775 | |

| Age (in years) | Mean (mean of mean) | 33.4 |

| Range | 4–79 | |

| Male : Female ratio | 1:5.63 | |

| Dermatological indications No. of patients | ||

| Pigmentary | Vitiligo | 266 (34.3%) |

| Melasma | 22 (2.8%) | |

| Lentigo, café au lait macules, post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation | 9 (1.1%) | |

| Not defined | 71 (9.1%) | |

| Acne and scars | 127 (16.3%) | |

| Vascular | 67 (8.6%) | |

| Rosacea | 30 (3.8%) | |

| Connective tissue disease | Lupus erythematosus | 46 (5.9%) |

| Morphea | 4 (0.5%) | |

| Not defined | 4 (0.5%) | |

| Scarring | 47 (6%) | |

| Naevus | 12 (1.5%) | |

| Others/undefined | 70 (9%) | |

The details of the included studies have been included in Table 3.

| S No. | Study, Year | Type |

No of patients (analysed) |

Age | Sex | Indication | Duration | Outcome measure | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Boehncke et al., 200210 | Prospective study | 20 | 16-69 |

M – 0 F – 20 |

Acne, Rosacea, CLE, Vitiligo | 2 weeks | DLQI |

Improved from 9.2 at baseline to 5.5. More improvement in less severe scores. |

|

| 2 | SA Holme et al., 200211 | Prospective study | 82 | 16-78 |

M – 6 F – 76 |

Pigmentary Scar Vascular Rosacea Others |

1 month | DLQI | Improved from 9.1 to 5.8. | |

| 3 | Bal Krishnan et al., 200512 | Prospective study | 63 | 19-46 |

M – 0 F – 63 |

Acne Pigmentary Vascular Rosacea naevi |

3 months |

Skindex-16 scores, FNE scores, QOL perception with and without facial blemish and worry about skin discoloration |

Skindex-16 – 59.8 to 40.2 FNE – 37.6 to 33.6 QOL perception with and without facial blemish – 4.2 to 1.4 Worry about skin discolouration – 8.8 to 4.7 |

|

| 4 | Ongenae, 200513 | Open label study | 62 | 16-68 |

M – 6 F – 56 |

Vitiligo | 1 month |

DLQI, Adapted stigmatisation questionnaire |

Significant improvement in DLQI – 7.3 to 5.9 Adapted stigmatisation questionnaire – 38.4% reduction |

Stigmatisation questionnaire |

| 5 | Matsuoka et al., 200614 | Randomised control |

50 A (25) – demonstration of use of cosmetics with treatment B(25) – only treatment |

A - 24±3 B – 25±5 |

M – 0 F - 50 |

Acne | 4 weeks | WHO QOL26 DLQI |

WHO QOL26 A – 3.27 to 3.39 B – 3.36 to 3.44 DLQI A – 8.24 to 3.88 B – 6.24 to 3.24 |

|

| 6 | Tedeschi et al., 200715 | Prospective study | 15 | 7–16 |

M – 3 F – 12 |

Acne Vitiligo Becker’s Naevus Striae distensae Allergic contact dermatitis Post-surgery scarring |

2 weeks | Satisfaction of parents in providing cover | ||

| 7 | Tanioka et al., 201016 | Prospective control study |

32 A – (21) – given camouflage lessons B – (11) – no lessons given |

A – 48.1 B – 40.8 |

M – A – 11 B – 6 F A – 10 B – 5 |

Vitiligo | 4 weeks | DLQI |

DLQI improvement in both groups A – 5.9 to 4.48 B – 3.18 to 4.36 Maximum improvement in item 2 |

|

| 8 |

Seite et al., 201217 |

Prospective study | 129 | 42±1.4 |

M – 7 F – 122 |

Acne Vascular Pigmentary Others |

4 weeks | DLQI |

Improved from 9.9 to 3.49 More improvement in item 9 with improvement in all other items. |

|

| 9 | Peuvrel et al., 201218 | Open prospective study | 63 | 4–79 |

M – 7 F – 79 (of the 86 recruited) |

Acne Rosacea Scars Vascular Pigmentary Connective tissue diseases |

1 month | DLQI |

Significant improvement in DLQI – 7.3 to 4.6 More improvement in acne, rosacea and scar Items 1 and 2 showed maximum improvement. |

Questionnaire of ease of application. |

| 10 | Padilla-Espana et al., 201319 | Case Report | 6 | 10-15 |

M – 1 F – 5 |

Acne Naevus Vitiligo |

2 weeks | cDLQI | Improvement in cDLQI – 10.6 to 4.33 | |

| 11 | Ramien,201420 | Open label prospective study | 38 | 5-18 |

M – 4 F – 37 (41 initially recruited) |

Vascular Naevus Vitiligo Post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation |

6 months | cDLQI |

Improved from 5.1 to 2.1 More improvement in pigmentary and vascular abnormalities. |

|

| 12 | Salsberg et al., 201521 | Open label prospective study | 22 | 5-17 |

M – 3 F – 19 |

Vascular Naevus Vitiligo Morphea Café au lait macules |

1 month |

cDLQI fDLQI |

Significant improvement cDLQI – 6.82 to 3.05 fDLQI – 7.68 to 4.68 |

|

| 13 | Oliveiria et al., 202022 | Randomised controlled intervention study |

43 A (28)– Intervention – use camouflage B (15)- control |

38-55 |

M – 0 F – 43 |

Systemic lupus erythematosus (Discoid, subacute cutaneous and acute lesions) |

24 weeks |

SLEQoL DLQI Rosenberg self-esteem scale HADS |

SLEQoL – A –118 to 96.5 B – 89 to 153 DLQI A – 8.5 to 3.5 B – 8.0 to 7.0 Rosenberg self-esteem scale A – 27 to 29.5 B – 27 to 29.0 Hospital Depression Scale A – 8.0 to 7.0 B – 5.0 to 5.0 Hospital Anxiety Scale A – 9.0 – 8.0 B – 6.0 – 9.0 |

|

| 14 | Bassioumy et al., 202023 | Prospective randomised study |

100 A (40) – camouflage group B (60) – control group |

4-70 |

M -56 F – 44 |

Vitiligo | 4 weeks | DLQI |

Improved A – 13.4 to 7.5 B – 11.9 to 10.6 |

Camouflage usage questionnaire |

| 15 | Morales et al., 202224 | Uncontrolled quasi experimental study | 45 | 42.4 ± 13.7 |

M – 10 F – 35 |

Vitiligo | 16 weeks |

VitiQol DLQI EQ5D SF36 |

VitiQol – 46.2 to 31.9 DLQI – 8.0 to 3.0 EQ5D– 82 to 90 SF36 – Emotional limitations 100 to 100 Emotional well-being 68 to 76 Social functioning 75 to 100 |

DLQI: Dermatology life quality index, FNE: Fear of negative evaluation, QOL: Indicates quality of life, WHOQOL26: World health organization (WHO)QOL26, cDLQI: Children’s dermatology life quality index, fDLQI: Family dermatology life quality index, SLEQoL: Systemic lupus erythematosus – specific quality of life scale, HADS: Hospital anxiety and depression scale, EQ5D: EuroQol-5 dimension questionnaire, SF36: Short form health survey, ViTiQol: Vitiligo quality-of-life index.

Quality of life measures analysed

Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI) was the most commonly used QOL index used in 10 of the 15 studies individually or in combination with other scoring systems. Similarly, Children DLQI (cDLQI) was a standard QOL used in studies on the paediatric population.25,26 The mean pre-treatment DLQI was 8.68 which reduced to 4.37 after camouflage therapy with maximum pre-treatment value being as high as 13.4 and minimum post-treatment value falling to 3.0. Similarly, a reduction in cDLQI was also observed with mean pre-treatment value of 7.5 and post-treatment value of 3.16.

DLQI comparison between diagnostic categories

Four studies discussed the QOL improvement in different diagnostic categories, mainly pigmentary, acne, vascular and scarring. Holme et al. observed maximum improvement in DLQI in scarring category (10.2–5.6) followed by vascular (8–3.3) and pigmentary (8.6–6.3) with p values <0.0001, <0.01 and <0.05, respectively.11 Seite et al. also reported a similar result with larger improvement of DLQI among patients with vascular disorders (5.35–3.26, P, 0.0001) but contrastingly smaller improvement among individuals with scars (5.52–4.39, P, 0.0001).17 Peuvrel et al. stated significant change in DLQI in two of the three disorder sub-groups, i.e., acne (p = 0.006) and rosacea (p = 0.036), and scar group also showed a decreasing trend (p = 0.057).18 Ramien et al. showed improvement in cDLQI in both main categories, namely, vascular and pigmentary. In vascular category, cDLQI reduced from 4.1 to 1.0 (p 0.003) and pigmentary anomalies from 6.2 to 3.2 (p – 0.020). Patients with vascular malformations showed maximum reduction from 5.5 to 1.5 (p - 0.002) under the vascular category.20

Individual parameter changes in DLQI

DLQI is a 10-item questionnaire analysing QOL under different spheres like symptoms and feelings, daily activities, leisure, work and school, personal relationship, and discomfort of treatment. Seven studies discussed the most affected items and further the items that showed most improvement and these have been described in Table 4. The most affected area was symptoms and feelings followed by daily activities and these parameters showed significant improvement in addition to leisure. But in the study by Holme et al. which was one of the earliest studies, the highest score was in the area of symptoms and feelings and daily activities and leisure. A reduction was observed in all scores post-camouflage use but interestingly personal relationship showed the most improvement with approximately 80% reduction in scores as compared to other parameters.11

| Study | Indication | Item affected | Item most improved |

|---|---|---|---|

| Holme et al.11 | Multiple | Symptoms and feelings, daily activities and leisure (2,4,5) | Personal relationships (8,9) |

| Ongenae et al.13 | Vitiligo | Symptoms and feelings and daily activities (2,4) | Symptoms and feelings, daily activities and leisure (1,2,4,6) |

| Matsouka et al.14 | Acne | Symptoms and feelings and daily activities (1,2,3,4) | Symptoms and feelings, daily activities, leisure and personal relationships (1,2,5,6,8,9) |

| Tanioka et al.16 | Vitiligo | All | Symptoms and feelings (1,2) |

| Seite et al.17 | Multiple | Symptoms and feelings (2) | Symptoms and feelings, daily activities and leisure (2,3,5) |

| Peuvrel et al.18 | Multiple | Data not available | Symptoms and feelings, daily activities (1,2,3,4) |

| Ramien et al.20 | Multiple | Data not available | Symptoms and feelings, daily activities and leisure (1,2,3,4,5) |

Other scores

Balkrishnan et al. discussed QOL improvement in various disorders using Skindex 16 which reduced from 59.8 to 40.2, fear of negative evaluation which reduced from 37.6 to 33.6, worry about skin discoloration which reduced from 8.8 to 1.4, and QOL perception with and without skin blemish which reduced from 4.2 to 1.4.12

Ongenae et al. in addition to DLQI used a stigmatisation questionnaire in which anticipation of rejection (56%, SD 21%) and guilt and shame (58%, SD 20%) are the most affected ones.13

Matsouka et al. used World Health Organization (WHO) QOL26 (WHOQOL 26) and DLQI in a comparative study on female acne patients. WHOQOL 26 was affected in all domains, and in the intervention group, maximum improvement was observed in the psychological domain.14

Olivieria et al. performed a comparative analysis in patients of systemic lupus erythematosus and used a disease-specific score Systemic Lupus Erythematosus – Specific Quality Of Life Scale (SLEQoL) which showed a significant reduction in the camouflage group (Friedman’s test p ¼ 0.005) with improvement in areas of mood and self-image and physical functioning. Psychological and self-esteem impact was assessed using the Rosenberg self-esteem scale score and anxiety and depression using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Although there were no statistically significant changes in the scores at follow-up, improvement in self-esteem (p - 0.041), anxiety (p - 0.045), and depression (p - 0.033) was still observed as an independent observation.22 Morales et al. studied 45 patients of vitiligo and used vitiligo-specific Vitiligo Quality-Of-Life Index which showed significant reduction from 46.2 ± 22.7 to 31.9 ± 20.4 and p <0.001. Another scoring system used was EuroQol-5 Dimension questionnaire, a visual analogue scale–based system and it showed improvement from 82 to 90 (p - 0.007). Short Form Health Survey analysed emotional limitations, emotional well-being, and social functioning which all showed improvement.24

Discussion

QOL of an individual is a major determinant of mental and social health, with ill health usually resulting in it’s deterioration. Dermatological disorders, especially chronic disfiguring dermatoses, are major contributors resulting in a decline of QOL and this has been well substantiated in literature. Over the years, physicians have tried to devise various techniques to help improve the QOL of their patients over and above therapeutic treatment. Camouflage forms an important subset of these techniques which, when used appropriately under the right guidance, proves to be an important tool in patients suffering from visible deformities of skin and associated structures.27-29

This review included studies focused on quantifying improvement in QOL of various dermatological disorders after camouflage therapy using various parameters of assessment [Table 1]. It was observed that camouflage can be used for multiple indications which can broadly be classified as pigmentary disorders, acne, vascular abnormalities, and scarring.

Pigmentary diseases including vitiligo, melasma, lentigo, café au lait macules, and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation were the most commonly evaluated indications, of which vitiligo was the most common. It was observed that DLQI assessment in these patients showed significant improvement in scores after camouflage use. Vitiligo was the most commonly studied pigmentary disorder, likely because it causes significant deformity in skin of colour as the colour discrepancy is more evident. These disorders prove to be an ideal dermatosis for camouflage therapy as the skin texture is maintained and only the skin colour needs to be corrected by a carefully matched skin shade. The improvement in QOL in these individuals was lesser when compared to other indications but this may be because of the stigma associated with it. This issue should be explored in larger studies.30-32 Some authors believe that camouflage therapy may hamper the treatment of vitiligo but Li et al. in 2020 found that there was no difference in repigmentation and transepidermal water loss in patients using dihydroxyacetone containing camouflage as compared to controls.33

Acne was another indication evaluated in the paediatric and the young adult population. Severe acne, mainly affecting the young adults, is an important cause of psychological stress leading to depression, anxiety and suicidal tendencies. Improvement in QOL with reduction in DLQI scores was observed in patients advised camouflage therapy in addition to medical treatment of acne.34,35 Cosmetics usually are considered to exacerbate acne and rarely advised by dermatologists. But Hayashi et al. in 18 female patients observed that make up designed for acne-prone skin did not worsen the severity of acne; rather, it significantly improved the QOL.36

Vascular lesions include a large variety like spider angiomas, port wine stain, haemangiomas, telangiectasia, etc., and the treatment options are often limited and have questionable efficacy. As observed, vascular lesions showed maximum improvement in QOL when compared to other indications. This may be due to the fact that these lesions especially on visible areas cause significant cosmetic disfigurement due to colour contrast. Camouflage using colour correction and correct skin matching may give an apparently normal appearance to the patients thereby improving QOL in lesions that may otherwise have minimal curative options.37-40

Camouflage by using colour correction and concealing may give an apparently normal appearance to the patients and thereby improve QOL in lesions that may otherwise have minimal curative options. Scarring due to acne, post-surgery, post-trauma or radiation causes change in both colour and texture of skin causing a visible deformity with scarce options of correction. Scars, although symbolising survival and being inevitable, may be a source of anxiety and stress to patients. Thus, scars when corrected with camouflage using contour correction help improve QOL. Camouflage used in patients immediately post-surgery to cover scars has been shown to improve QOL and provide better recovery psychologically.41-44

In the studies in this review, a vast array of scoring systems were utilised, the most common being DLQI which is a widely used and validated QOL measure designed for dermatology patients. As reviewed, camouflage therapy showed improvement in symptoms and feelings questions of the questionnaire signifying that it decreases the feelings of embarrassment and self-consciousness in the patients about their appearance due to the skin disease.25,26 Other scoring systems also showed similar patterns of improvement in areas of appearance, self-esteem and psychological well-being. These scores helped to objectively evaluate the efficacy of camouflage in improving QOL and validate its utility in regular clinical dermatological practice.

Conclusion

The evidence presented here gives us an insight into the positive effects of camouflage/cover up make up when offered to patients with different dermatological conditions. It leads us to reflect and re-analyse the supportive clinical care of patients with visible disfigurements beyond standard treatment protocols and encourages us to explore the field of camouflage therapy to provide better QOL to our patients.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- Make-up as an adjunct and aid to the practice of dermatology. Dermatol Clin. 1991;9:81-8.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skin camouflage-A guides to remedial techniques: Cover creams. Stanley Thornes publishers; 1985. p. :18-33.

- n.d. Available from: https://skin-camouflage.net/scwp/index.php/history-of-skin-camouflage/?cn-reloaded=1. [Last accessed on 2023 October 15]

- The contribution of skin camouflage volunteers in the management of vitiligo. Case Reports. 2011;2011:bcr0920114783.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Changing faces. Available from: https://www.changingfaces.org.uk/services-support/skin-camouflage-service/. [Last accessed on 2023 October 15]

- Knowledge, attitude, and practice of cosmetic camouflage among dermatology residents. Pigment Int. 2021;8:166-72.

- [Google Scholar]

- Decorative cosmetics improve the quality of life in patients with disfiguring skin diseases. Eur J Dermatol. 2002;12:577-80.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosmetic camouflage advice improves quality of life. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:946-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrective cosmetics are effective for women with facial pigmentary disorders. Cutis. 2005;75:181-7.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life and stigmatization profile in a cohort of vitiligo patients and effect of the use of camouflage. Dermatology. 2005;210:279-85.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effects of skin care and makeup under instructions from dermatologists on the quality of life of female patients with acne vulgaris. J Dermatol. 2006;33:745-52.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camouflage for patients with vitiligo vulgaris improved their quality of life. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2010;9:72-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Interest of corrective makeup in the management of patients in dermatology. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2012;5:123-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of quality of life after a medical corrective make-up lesson in patients with various dermatoses. Dermatology. 2012;224:374-80.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camouflage therapy workshop for pediatric dermatology patients:A review of six cases. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2014;105:510-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life in pediatric patients before and after cosmetic camouflage of visible skin conditions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:935-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of cosmetic camouflage on the quality of life of children with skin disease and their families. J Cutan Med Surg. 2016;20:211-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosmetic camouflage improves health-related quality of life in women with systemic lupus erythematosus and permanent skin damage: A controlled intervention study. Lupus. 2020;29:1438-48.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosmetic camouflage as an adjuvant to vitiligo therapies: Effect on quality of life. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020;00:1-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effect of cosmetic camouflage in adults with vitiligo. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2022;113:316-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermatology life quality index (DLQI) – a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical experience and psychometric properties of the children’s dermatology life quality index (CDLQI), 1995–2012. Br J Dermatol. 2013;169:734-59.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life assessment among patients suffering from different dermatological diseases. Saudi Med J. 2021;42:1195-200.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Alterations in mental health and quality of life in patients with skin disorders: A narrative review. Int J Dermatol. 2022;61:783-91.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quality of life in patients with vitiligo: An analysis of the dermatology life quality index outcome over the past two decades. Int J Dermatol. 2016;55:608-14.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosmetic camouflage in vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol. 2010;55:211-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camouflage for patients with vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2012;78:8-16.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of the potential interference of camouflage on the treatment of vitiligo: An observer-blinded self-controlled study. Dermatologic Therapy 2020:e14545.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skin disease in children: Effects on quality of life, stigmatization, bullying, and suicide risk in pediatric acne, atopic dermatitis, and psoriasis patients. Children (Basel). 2021;8:1057.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Metabolic status, obesity, and quality of life in patients with acne vulgaris: A cross-sectional case-control study. Indian J Dermatol. 2021;66:223.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Make-up improves the quality of life of acne patients without aggravating acne eruptions during treatments. Eur J Dermatol. 2005;15:284-7.

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient’s evaluation of argon laser therapy of port wine stain, decorative tattoo, and essential telangiectasia. Lasers Surg Med. 1984;4:181-90.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological disabilities amongst patients with port wine stains. Br J Dermatol. 1989;121:209-15.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutaneous vascular lesions. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2013;21:111-26.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The art of corrective makeup: How to camouflage unattractive scars and blemishes. New York, NY: Doubleday; 1984.

- Medical makeup for concealing facial scars. Facial Plast Surg. 2012;28:536-40.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recommendations for the use of corrective makeup after dermatological procedures. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2022;21:1554-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Camouflage therapy in aesthetic surgery. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:813-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]