Translate this page into:

The impact of the latest classification system of benign vulvar diseases on the management of women with chronic vulvar pruritus

2 Department of Pathology, Ministry of Health, Adana Numune Education and Research Hospital, Seyhan Practice Center, Adana, Turkey

3 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ministry of Health, Adana Numune Education and Research Hospital, Seyhan Practice Center, Adana, Turkey

Correspondence Address:

Kiymet Handan Kelekci

Basinsitesi mahallesi, In�n� caddesi No: 447 D: 4, Karabaglar, Izmir

Turkey

| How to cite this article: Kelekci KH, Adamhasan F, Gencdal S, Sayar H, Kelekci S. The impact of the latest classification system of benign vulvar diseases on the management of women with chronic vulvar pruritus. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2011;77:294-299 |

Abstract

Background: The management of women with chronic benign vulvar dermatoses has been one of the most difficult and challenging aspects of women's healthcare for a long time. Aim: Our aim was to compare the ability to approach the specific diagnosis of nonneoplastic and noninfectious vulva diseases, between the new classification system and the old classification system. Methods: One hundred women with chronic vulvar pruritus were included in the study. After detailed examination of the vulva, all visible lesions were biopsied, with normal skin included. All specimens was sent for dermatopathology and examined simultaneously under a binocular microscope by two pathologists. Specific diagnosis if possible and histopathological findings were classified according to both the 1987 and 2006 International Society for the Study of Vulvar Diseases (ISSVD) classifications. The ratios that were able to be approached on the specific diagnosis, with the aid the two classification systems, were compared. Results: Specific clinical diagnosis by both pathological and after using clinicopathological correlation was possible in 69 out of 91 patients (75.8%) according to the 1987 ISSVD classification, and in 81 out of 91 patients (89.0%) according to the ISSVD 2006 classification system. The difference in the clinical diagnosis ratios between the two classification systems was statistically significant ( P < 0.05). In a subgroup of women without specific diagnosis at the time of pathological examination, clinical diagnosis was made in 28 out of 50 women (56%) after using the clinicopathological correlation according to the ISSVD 1987 classification, whereas, specific diagnosis was made in 39 out of 49 (79.6%) women after using the clinicopathological correlation according to the ISSVD 2006 classification. The difference was statistically significant in terms of the ratio of the ability to achieve a specific diagnosis ( P < 0.01). Conclusion: ISSVD 2006 classification of nonneoplastic and noninfectious vulvar disease is more useful than the former classification, in terms of approaching the specific diagnosis of vulvar dermatoses.Introduction

Skin diseases of the vulva are a significant and important group of dermatological conditions that may be associated with considerable morbidity, discomfort, and embarrassment. The most common conditions seen in a Dermatology Clinic are vulvar dermatoses, which comprise of lichen sclerosis, lichen planus, vulvar eczema, and psoriasis. Other conditions such as vulvar pain syndromes, vulvar disorders associated with systemic diseases, and blistering diseases are also seen. [1] These conditions are clinically difficult to recognize because the warm, moist, frictional environment of the vulva regularly obscures what would otherwise be their characteristic morphological hallmark. [2],[3] Vulvar dermatoses, most troublesome for both clinicians and pathologists are benign inflammatory disorders. Given the frequency of the dermatological disease, vulvar biopsy and analysis by a dermatopathologist are recommended in patients with chronic vulvar pruritus.

Women with vulvar pruritus may present to a wide variety of specialists, including gynecologists, genitourinary medicine physicians, geriatricians, general practitioners, and dermatologists. Vulvar dermatoses has been studied and treated by clinicians of different training backgrounds, hence, it is not surprising that differences in concepts, classifications, and terminology have arisen. [4] Thirty years ago, the International Society for the Study of Vulvovaginal Disease (ISSVD) recognized that a group of benign, noninfectious vulvar diseases needed to be defined and classified in order to clearly separate these benign disorders from premalignant and malignant epithelial conditions. ISSVD recommended that the classification of the benign, noninfectious vulvar disease, which has been in place, would employ the standard terminology used by dermatologists and dermatopathologists. [1],[5]

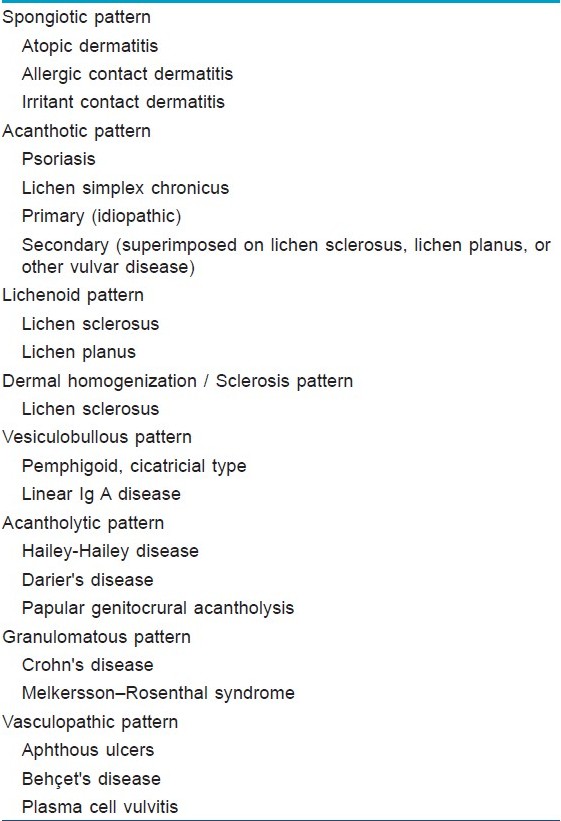

The ISSVD classification is an attempt by a multidisciplinary body to explain vulvar disease in a manner acceptable to all specialties involved, and has been accepted by the World Health Organization (WHO). [6] A recent consensus conference defined noninfectious and nonneoplastic vulvar disorders according to histological patterns, based on used and respected dermatopathology textbooks. These definitions are spongiotic pattern, acanthotic pattern, lichenoid pattern, dermal homogenization / sclerosis pattern, vesiculobullous pattern, acantholytic pattern, granulomatous pattern, and vasculopathic pattern. [5],[7] The chance of receiving a definable, dermatological diagnosis increases with the pathologist′s experience level with inflammatory skin disease.

This article′s aim is to evaluate and review the impact of the ISSVD 2006 classification on the ability to achieve a specific diagnosis of the most common skin disease affecting the vulva with pruritus, seen by dermatologists.

Methods

This study was conducted in the Dermatology and Gynecology Outpatient Clinics of the Seyhan Practice Center of the Adana Numune Education and Research Hospital, between January, 2008 and September, 2009. The study was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee and all the participants gave informed consent before inclusion in the study. Most of patients were referred to our clinic from the Gynecology Department because of a possible diagnosis of chronic vulvar dystrophy. A total 112 women with chronic vulvar pruritus that did not respond to treatment as expected, with topical steroid and antifungal, for longer than six months and without systemic pruritus, made up the study group. Infections, vulvar intra-epithelial neoplasia (VIN), malignant conditions, and vulvar pruritus caused by systemic disorders were excluded. Systemic involvement was encountered in 12 patients. They were not included in the study. Vulvar lesions that caused concern, but were not symptomatic, such as melanosis vulvae, angiokeratomas, vulvar varicosities, vitiligo, and lymphangiectases were seen during the study period, but were not included in this series.

A biopsy was performed on all patients, under local anesthesia. For vulvar skin biopsy, a 4-mm punch biopsy forceps was used. Specimens were sent immediately for dermatopathology. Specific diagnosis was described in only 20 women before the pathological examination.

These specimens had been formalin-fixed and embedded in paraffin. Five-micrometer thick sections were cut from the formalin-fixed tissue embedded in paraffin blocks. The hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) stained section slides were examined by both the pathologists (FA, HS). All the specimens were examined by two pathologists simultaneously according to the ISSVD 1987 classification and the ISSVD 2006 classification. First, 50 specimens were examined according to the ISSVD 1987 classification [Table - 1] and the other 50 specimens were examined according to the ISSVD 2006 classification. Second, two weeks later each of the 50 remnant specimens of both groups were cross examined by the same pathologists simultaneously, according to the two classification systems. They were blinded to the previous examination. The histopathological patterns and specific diagnosis were recorded, if possible. The classification of nonneoplastic epithelial disorders of the skin and mucosa of the vulva was performed in accordance with the ISSVD 2006 classification [Table - 2]. The spongiotic pattern, acanthotic pattern, lichenoid pattern, dermal homogenization / sclerosis pattern, vesiculobullous pattern, acantholytic pattern, granulomatous pattern, and vasculopathic pattern were reported. If they met two or more histological patterns, everything was recorded together. In women without specific diagnosis after pathological examination, specific diagnosis was performed after using the clinicopathological correlation according to the histopathological pattern and probable clinical diagnosis.

The demographic data of patients, duration of symptoms, dermatological findings and diagnoses, and the dermatopathological pattern and / or specific diagnosis according to either the former or latter ISSVD classifications were recorded.

All data were analyzed by the SPSS packet program (SPSS, 17.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The results were expressed as mean ± SD and range, minimal and maximal values. A comparison was made between two groups in terms of the ability to achieve the clinical diagnosis ratios using the student′s t-test. Statistical significance was considered as P < 0.05.

Results

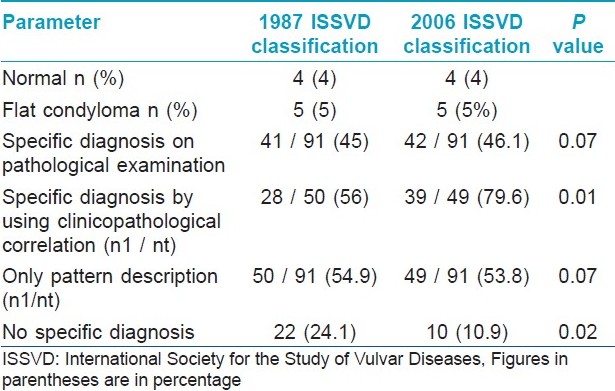

The mean age of our study group was 47 years (range, 13 - 82 years). Of these 56% were postmenopausal, 35 out of 100 women were in the reproductive age, and nine out of 100 women were premenarchal. Mean duration of symptoms was 21 months (range, 6 - 120 months). A total of 20 women were diagnosed clinically before vulvar biopsy. Four biopsies (4%) demonstrated nonspecific changes and five biopsies (5%) demonstrated flat condylomata, whereas, the remaining 91 (91%) showed clinically relevant pathological diagnosis. Therefore, these nine cases were excluded from the statistical analysis. All patients were classified based on the histological morphology, according to the two classification systems. In cases without specific clinical diagnosis, only the histopathological patterns were recorded.

Specific clinical diagnoses were diagnosed in 41 out of 91 (45%) patients according to the former classification, and in 42 out of 91 (46.1%) women according to the ISSVD 2006 classification [Table - 3]. The difference of specific clinical diagnosis ratios between the two classification systems was not statistically significant ( p0 = 0.054).

The histopathological pattern description, without specific clinical diagnosis ratios, were (50 / 91) 54.9% and (49 / 91) 53.8% in the former classification system and the newest ISSVD 2006 classification system, respectively. The two groups did not differ with respect to the only histopathological pattern description rates ( p0 = 0.052).

According to the 2006 ISSVD classification, the distribution of histopathological patterns in our patients was as follows: 48 patients - acanthotic pattern, 21 patients - spongiotic pattern, 10 patients - lichenoid pattern, three patients - dermal homogenization / sclerosus pattern, one patient - vesiculobullous pattern, one patient - acantholytic pattern, and seven patients - a combination of two or more patterns. In cases of two or more histological patterns, using the clinicopathological correlation, the clinician determined the most likely diagnosis according to the dominant pattern.

Among the specific clinical diagnosis, lichen simplex chronicus was the most common vulvar dermatoses (17 / 60, 28.3%). Twelve patients were given a diagnosis of lichen sclerosus, 11 patients were diagnosed with allergic contact dermatitis. Ten patients and three patients were diagnosed with psoriasis and lichen planus, respectively. The other rare diagnoses were vitiligo (two patients), erythema dyschromicum perstans (one patient), syringoma (two patients), and postinflammatory pigmentation (two patients).

Specific clinical diagnoses by both pathological and after using clinicopathological correlation were allowed in 69 out of 91 patients (75.8%) according to the 1987 ISSVD classification, and in 81 out of 91 patients (89.0%) according to the ISSVD 2006 classification system. The difference of clinical diagnosis ratios between the two classification systems was statistically significant ( p0 < 0.05).

In the subgroup of women without specific diagnosis at the time of pathological examination, clinical diagnosis was made in 28 out of 50 women (56%) after using the clinicopatological correlation according to the ISSVD 1987 classification, whereas, specific diagnosis was made in 39 out of 49 (79.6%) women after using the clinicopatological correlation according to the ISSVD 2006 classification. The difference was statistically significant in terms of the rate of ability to achieve a specific diagnosis ( p0 < 0.01).

Discussion

Vulvar cutaneous disorders represent a diverse spectrum of diseases commonly encountered by the dermatologist, gynecologist, family practitioner, and other clinicians. The management of women with chronic benign vulvar conditions has been one of the most difficult and challenging aspects of women′s healthcare for a long time. A more useful classification of the vulvar nonneoplastic and noninfectious diseases was needed. In comparison with the two classification systems of vulvar dermatoses, our preliminary study showed that the 2006 ISSVD classification was more capable of making a diagnosis in 12 additional patients than the 1987 ISSVD classification of 100 women with chronic vulvar pruritus.

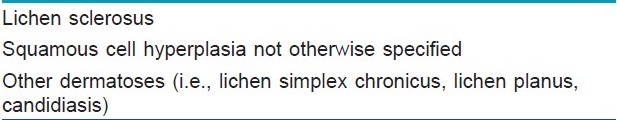

In the mid-1970s, in an attempt to construct a universal nomenclature for vulvar lesions that would be acceptable to the various specialities, the ISSVD adopted a classification of vulvar dystrophies. This classification was subsequently modified in 1985, with the elimination of the term dystrophy. [8] Included under the title of nonneoplastic epithelial alterations of the vulva in this classification are lichen sclerosus, squamous cell hyperplasia not otherwise specified, and other dermatoses. The iteration currently in place for the nonneoplastic epithelial disorder was published. [9] In this classification, the term ′hyperplastic dystrophy′ was replaced by the more descriptive term ′squamous cell hyperplasia′. It was controversial from the outset, and since then it has been increasingly criticized. The ISSVD 1987 classification was too restrictive. Squamous cell hyperplasia was a weakness of the ISSVD classification. Squamous cell hyperplasia, is a histopathological rather than a clinical term, and probably describes lichenification, which is a secondary phenomenon rather than a disease. [6] Due to increasing, widespread dissatisfaction, four years ago, the ISSVD elected to reconsider this classification. They then considered a classification based on microscopic morphology. The ISVDD 2006 classification is based largely on histological morphology. Among various specialties and diverse languages, the nomenclature of histological morphology is appreciably more standardized than that of clinical morphology. [5] They settled on this approach in as much as there is surprising worldwide uniformity of the terminology used in pathology. [10]

When clinicians established a clinical diagnosis, there is no need for a classification of any sort once the diagnosis is known. Conversely, when clinicians encounter an unrecognized disorder, the next logical step is to perform a biopsy. Subsequently, if the pathologist makes a specific diagnosis, once again there is no need for a classification. The real need for a classification arises only when neither the pathologist nor the clinician can be certain of the correct diagnosis. In this setting, the pathologist describes the microscopic findings and histological pattern and indicates a necessity for the clinician to use the clinicopathological correlation, to arrive at the most likely diagnosis. [11] In our study, 20 women were diagnosed clinically and 42 specific diagnosis were determined pathologically according to the 2006 ISSVD classification. In reality, the necessity to use the clinicopathological correlation to achieve the most likely diagnosis of vulvar dermatoses was needed in 39 (42.8%) women. In this situation the pathologist offered a likely description of the histological pattern without committing to a specific diagnosis. Consequently, 11 additional cases to that of the 1987 classification, were determined by using the clinicopathological correlation in this subgroup. This was both clinically and statistically significant.

Because of its warm, moist, frictional environment, the vulva regularly obscures what otherwise would be its characteristic morphologic hallmarks, the diagnosis of benign vulvar disorders is difficult. [12] Therefore, vulvar biopsy is necessary in most cases, especially in women with chronic vulvar pruritus. In our study all referred women with chronic disorder were biopsied, to rule out both vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia and to evaluate to approach the specific diagnosis with the aid of the newest classification system.

Squamous cell hyperplasia is a diagnosis of exclusion. It includes a wide variety of lesions that do not fit the patterns of specific dermatological lesions. The histological features include acanthosis and a variable degree of hyperkeratosis. Squamous cell hyperplasia has an inappropriate position in the 1987 classification, because it is relatively rare in isolation, in clinical practice. Additionally, it seems that clinicians and pathologists confuse the term with the much more common lichen chronicus, which has squamous cell hyperplasia as one of its principal features. In a review of 114 nonneoplastic vulvar biopsy specimens by a multidisciplinary clinic specializing in nonneoplastic vulvar disease, the most common diagnosis was lichen simplex chronicus, and a diagnosis of squamous hyperplasia was not rendered in any case. [13] These authors concluded that the term squamous cell hyperplasia is a weaknesss in the 1987 ISSVD classification and that the place of this diagnosis in the ISSVD classification needs to be reviewed. In this series, the histological diagnoses were lichen sclerosus 25%, lichen simple chronicus 35%, nonerosive inflammatory dermatoses comprising of psoriasis, spongiotic dermatitis, dermatophytosis, and psoriasiform dermatitis 13%, erosive vulvitis and lichen planus 9%, nonspecific inflammation 6%, miscellaneous 9%, and normal 4%. In our study, the most common specific diagnosis was lichen simplex chronicus and the second was lichen sclerosus. Ambros et al., reported that most nonneoplastic white and red patches on the vulva seem to represent lichen sclerosus, lichen simplex chronicus superimposed on lichen sclerosus. [4] Other less common dermatoses do occur, but might not be recognized if the gynecologist and general surgical pathologist do not consider them in the differential diagnosis. [13]

The present report has a number of strengths: the prospective blindly comparative nature and it being the first report, as we know, about the impact of the newest classification system of nonneoplastic and noninfectious vulvar diseases on the approach of all specific diagnosis of the chronic vulvar pruritus. This study also has a few notable limitations: the lack of control group and number of women. Nonetheless, it is unlikely that these limitations would significantly affect the result of the study.

In conclusion, the management of women with chronic vulvar dermatoses has been one of the most difficult and challenging aspects of women′s healthcare for a long time. This preliminary study shows that the 2006 ISSVD classification of non-neoplastic and noninfectious vulvar diseases is more useful than the 1987 classification in terms of approaching the specific diagnosis of dermatoses.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Mrs. Stephanie Boran for the linguistic revision and also thank Mrs Ozlem Duvarcύ from the έzmir Technology Institute for the statistical analysis.

| 1. |

Salim A, Wojnarowska F. Skin diseases affecting the vulva. Curr Obstet Gynaecol 2005;15:97-107.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Broardman LA, Kennedy MC. Diagnosis and management of vulvar skin disorders. Obstet Gynaecol 2008;111:1243-50.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Wojnarowska F, Cooper SM. Anogenital (Nonveneral) Disaese. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizza JL, Rapini RP, editors. Dermatology. 2 nd ed. USA: Mosby; 2007. p. 1099-124.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Ambros RA, Malfetano JH, Carlson A, Mihm MC. Non-neoplastic epithelial alterations of the vulva: Recognition assessment and comparisons of terminologies used among the various specialties. Mod Pathol 1997;10:401-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Lynch PJ, Moyal- Barrocco M, Bogliatto F, Micheletti L, Scurry J. 2006 ISSVD Classification of vulvar dermatoses. Pathologic subsets and their clinical correlates. J Reprod Med 2007;52:3-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Fischer GO. The commonest causes of symptomatic vulvar disease: A dermatologist's perspective. Australas J Dermatol 1996;3:12-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Neill SM. Noninfectious inflammation and systemic diseases of the vulva. A vulvar disease clinicopathological approach. In: Heller DS, Wallach RC, editors. 1 st ed. New York: Informa Healthcare USA; 2007. p. 37-65.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Ridley CM. Nomenclature of non-neoplastic vulvar conditions. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1986;115;647-51.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Burdick B. Clarifying the "Report of the ISSVD Terminology Committee". J Reprod Med 1988;33:97-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Lynch PJ, Barocco MM, Bogliatto F, Micheletti L, Scurry J. 2006 ISSVD classification of vulvar dermatoses. J Reprod Med 2007;52:3-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Lynch PJ. 2006 International Society fort he Study of Vulvovaginal Disease Classification of Vulvar dermatoses; A Synopsis. J Low Genit Tract Dis 2007;11:1-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Sanchez NP, Mihm MC Jr. Reactive a neoplastic epithelial alteration of the vulva. J Am Acad Dermatol 1982;6:378-88.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

O'Keefe RJ, Scurry JP, Dennerstein G, Sfameni S, Brenan J. Audit of 114 non-neoplastic vulvar biopsies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1995;102:780-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

4,501

PDF downloads

3,305