Translate this page into:

The use of dermoscopy in distinguishing the histopathological subtypes of basal cell carcinoma: A retrospective, morphological study

Corresponding author: Assist. Prof. Mirjana Popadić MD, MSc, Faculty of Medicine, University of Belgrade, Clinic of Dermatovenereology, University Clinical Centre of Serbia, Belgrade, Serbia. mirjana.popadic@med.bg.ac.rs

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Popadić M, Brasanac D. The use of dermoscopy in distinguishing the histopathological subtypes of basal cell carcinoma: A retrospective, morphological study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2022;88:598-607.

Abstract

Background

The role of dermoscopy in distinguishing the histopathological subtypes of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is not fully elucidated.

Aims

To determine the accuracy of dermoscopy in diagnosing different BCC subtypes.

Methods

The dermoscopic features of 102 histopathologically verified BCCs were studied retrospectively. The tumours were classified as superficial (n=33,32.3%), nodular (n=46,45.1%) and aggressive (n=23,22.6%) BCCs by histopathology. Statistical analysis included Cohen’s kappa test, proportion of correlation, measures of diagnostic accuracy, diagnostic odds ratio and the credibility ratio of positive (LR+) and negative (LR−) tests.

Results

The highest value in all performed tests was seen in superficial BCCs (kappa 0.85; proportion of correlation 93%; diagnostic accuracy 93.1%), good correlation was noted in nodular BCCs (kappa 0.62, proportion of correlation 80%; diagnostic accuracy 80.4%) but dermoscopic correlation with histopathology was low for aggressive BCCs (kappa 0.13; proportion of correlation 79%; diagnostic accuracy 78.4%). Short, fine telangiectasias (83.3%) showed the greatest importance for the diagnosis of superficial BCCs, blue-grey ovoid nests (61.8%) had the highest diagnostic accuracy in nodular BCCs, while arborising vessels (79.4%) was the most significant dermoscopic feature for the diagnosis of aggressive BCCs.

Limitations

This was a retrospective analysis and included only Caucasian patients from a single centre.

Conclusion

The highest agreement of dermoscopic features with the histologic type was found in superficial BCCs. We did not find any specific dermoscopic structure that could indicate a diagnosis of aggressive BCC. The presence of relevant dermoscopic features in the evaluated cases was determined by the depth of tumour invasion and not by its histology.

Keywords

Dermoscopy

histopathology

correlation

superficial basal cell carcinoma

nodular basal cell carcinoma

aggressive basal cell carcinoma

Plain language summary

There is no distinctive dermoscopic feature that would indicate the aggressiveness of basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Spoke-wheel pigmentation was the only exclusive dermoscopic feature found in superficial BCC. All other dermoscopic features were present in various combinations and different frequencies in all evaluated histologic subtypes of BCC.

Introduction

Basal cell carcinomas (BCC) are slow growing, locally aggressive epithelial skin tumours exhibiting different elements (sebaceous, apocrine, eccrine and follicular) and having many different microscopic forms.1,2 From a therapeutic point of view, all variants of BCC can be classified into three major groups: superficial, nodular and aggressive (infiltrative, morpheaform, micronodular and basosquamous) BCCs.3-5

The accuracy of dermoscopy in differentiating the histologic subtypes of BCC has been the subject of multiple studies,6-12 but the results have been variable, even contradictory, especially in aggressive BCCs. Thus, we aimed to reevaluate the role of dermoscopy in differentiating the histologic forms of BCC. We also assessed the level of correlation of dermoscopic with histopathologic diagnosis in the different subtypes of BCC and evaluated specific dermoscopic features associated with the different histopathological types of BCC.

Methods

This retrospective, morphological study was conducted over a six-year period (2012–2017) at the University Clinic of Dermatovenereology, Belgrade, Serbia. All the patients selected for study were outpatients with histopathologically verified BCCs who had previously undergone dermoscopic evaluation. The study was approved by the ethic committees of the Clinic of Dermatovenereology and the Faculty of Medicine in Belgrade. The selection criteria are outlined in Table 1.

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

|

|

BCC: Basal cell carcinoma

Patient demographics were obtained from patient protocols. The location (categorised into the head and neck region, trunk and extremities), clinical form, number of BCC and diameter were noted. Based on the clinical morphology, BCCs were classified as superficial (non-elevated or slightly elevated lesions), nodular or aggressive (below skin level).

Dermoscopic evaluation

A DermLite DL3N handheld dermatoscope mounted on a digital camera or mobile smartphone was used to obtain contact polarised and non-polarised digital dermoscopic images at 10-fold magnification. The dermoscopic images were evaluated by pattern analysis13 for the presence of pigmented, vascular and other dermoscopic features of the BCCs.

The relevant dermoscopic features of BCCs are delineated in Table 2. BCCs were classified as superficial based on the presence of features of superficial BCCs and the absence of major criteria for nodular BCCs (blue pigmentation, arborising vessels, ulceration). Superficial BCC showing blue pigmentation, arborising vessels or ulceration were classified as nodular. BCCs with predominantly white-red unstructured areas and/or white short lines, were categorised as aggressive BCCs. Dermoscopic classification was performed without prior knowledge of the histopathological type of BCC.

| Superficial | Nodular | Aggressive |

|---|---|---|

| Pigmented •Multiple brown/grey globule •Spoke-wheel pigmentation •Leaf-like pigmentation •Brown/grey dots in focus •Concentric structures Vascular •Short fine telangiectasias Non-pigmented/non-vascular •Multiple small erosions •White-red unstructured areas Absence of blue pigmentation, typical arborising vessels and ulceration |

Pigmented •Large blue-grey ovoid nests •Multiple blue/grey globules Vascular •Typical arborising vessels Non-pigmented/non vascular •Ulceration •White-red unstructured areas |

Pigmented •Large blue-grey ovoid nests •Multiple blue/grey globules Vascular •Subtle arborising vessels Non-pigmented/non-vascular •Ulceration •White-red unstructured areas •Short white lines |

Histopathological classification

Lesions were classified histopathologically into superficial, nodular and aggressive types. Owing to the small number of individual aggressive tumour types, all mixed BCCs were aggregated into this category for valid statistical comparison with superficial and nodular types. The superiority rule was applied in mixed BCCs according to the most unfavourable subtype: aggressive > non-aggressive. In the case of mixing of two non-aggressive subtypes, tumour thickness was considered: nodular > superficial. If the superficial BCC was combined with nodular, it was classified as nodular BCC.

Thus, the superficial group included only purely superficial BCCs and the nodular group included nodular and its combinations (nodular-superficial, nodular-adenoid, nodular-cystic and infundibulocystic). The aggressive group consisted of all types of high-risk BCCs, either alone or in combination with some type of low aggressive tumours (superficial or nodular) including micronodular (MN), infiltrative (I) and its mixed variants (infiltrative-nodular (IN), infiltrative-superficial (I-S) and infiltrative-metatypical (I-MT)).

Statistical analysis

We assessed the diagnostic validity (i.e., the correctness of the diagnostic decision) of dermoscopy using histopathology as the gold standard (a diagnostic test considered to be the most accurate in diagnosing a disease).

Measures of diagnostic accuracy used were sensitivity (Sn), specificity (Sp), positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV), credibility ratio and diagnostic odds ratio (DOR). Sensitivity is the ability of a test to identify those who actually have the disease. Specificity is the ability of the test to rule out the existence of the disease. Positive predictive value represents proportion of subjects with disease among those with positive diagnostic tests, whereas negative predictive value represents proportion of subjects with disease among those with negative diagnostic tests. The credibility ratio shows how much the test result changes the pre-test probability of illness that is, the chance of illness. A positive test (LR+) indicates how many times a positive test result increases a pre-test chance of illness (preferably as high as possible), and a negative test likelihood ratio (LR−) indicates how many times a negative test result reduces a pre-test chance of illness (preferably values close to 0). The DOR is a summary indicator of the diagnostic performance of the test, representing the ratio of chances of the test being positive in the patient to the test being positive in healthy individual.

All measures of diagnostic accuracy were calculated according to standard formulas. Cohen’s kappa test and proportion of correlation were used to determine agreement of dermoscopic with histological diagnosis. All collected data were analysed using the SPSS 22.0 software package.

Results

The study included 62 patients (35/56% female and 27/44% male) with 102 histopathologically verified BCCs. Forty six patients had a single BCC, while 16 patients had multiple BCCs (10 patients with 2 BCCs, one with 4 BCCs, 2 each with 5 and 6 BCCs and 1 patient with 10 BCCs). The mean age of the patients was 66.4 years (median 68.5, range 32–85 years). The mean diameter was 13.6 mm (median 12 mm, range 4–37 mm). Forty eight BCCs (47.1%) were located on the head and neck, 37 (36.3%) on the trunk and 17 (16.7%) on the extremities.

Nodular BCCs (46 lesions, 45.1%) were the most frequent type, followed by superficial (33, 32.3%) and aggressive (23 lesions, 22.6%) BCCs [Figures 1–4]. Of the 46 nodular BCCs, 27 were purely nodular while the rest were mixed (11 were nodular-superficial, 6 nodular-adenoid, 1 each nodular-cystic and one nodular-infundibulocystic). The 23 aggressive BCCs comprised 3 micronodular, 4 purely infiltrative and 16 mixed (12 infiltrative-nodular, 3 infiltrative-superficial and 1 infiltrative-metatypical) types.

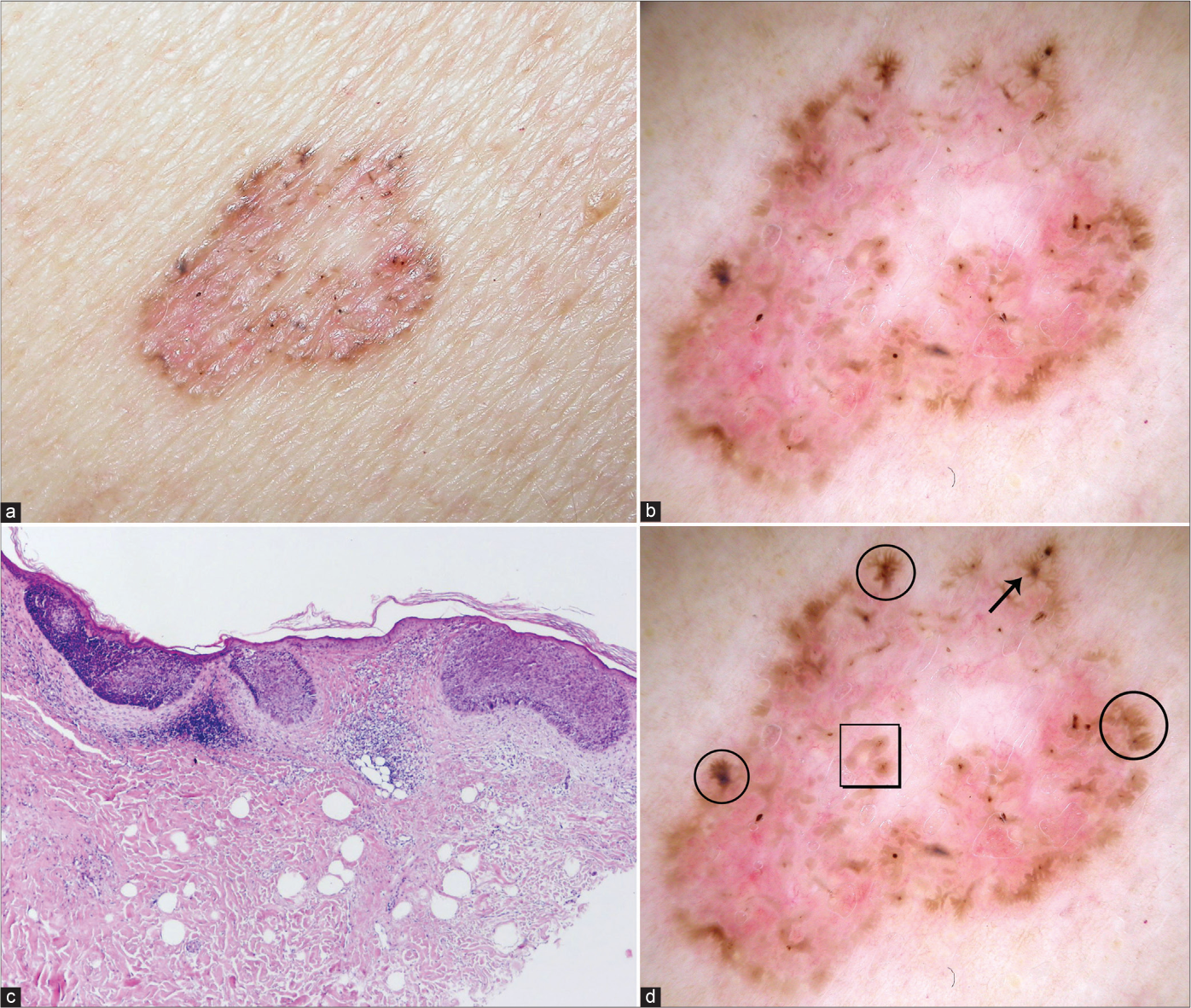

- Superficial basal cell carcinoma with typical clinical (a), dermoscopic (b) and histological (c) presentation (haematoxylin and eosin ×40). Dermoscopic view: leaf-like pigmentations (circles), concentric structures (square), spoke-wheel pigmentation (arrow), (d) Figure 1b with markings.

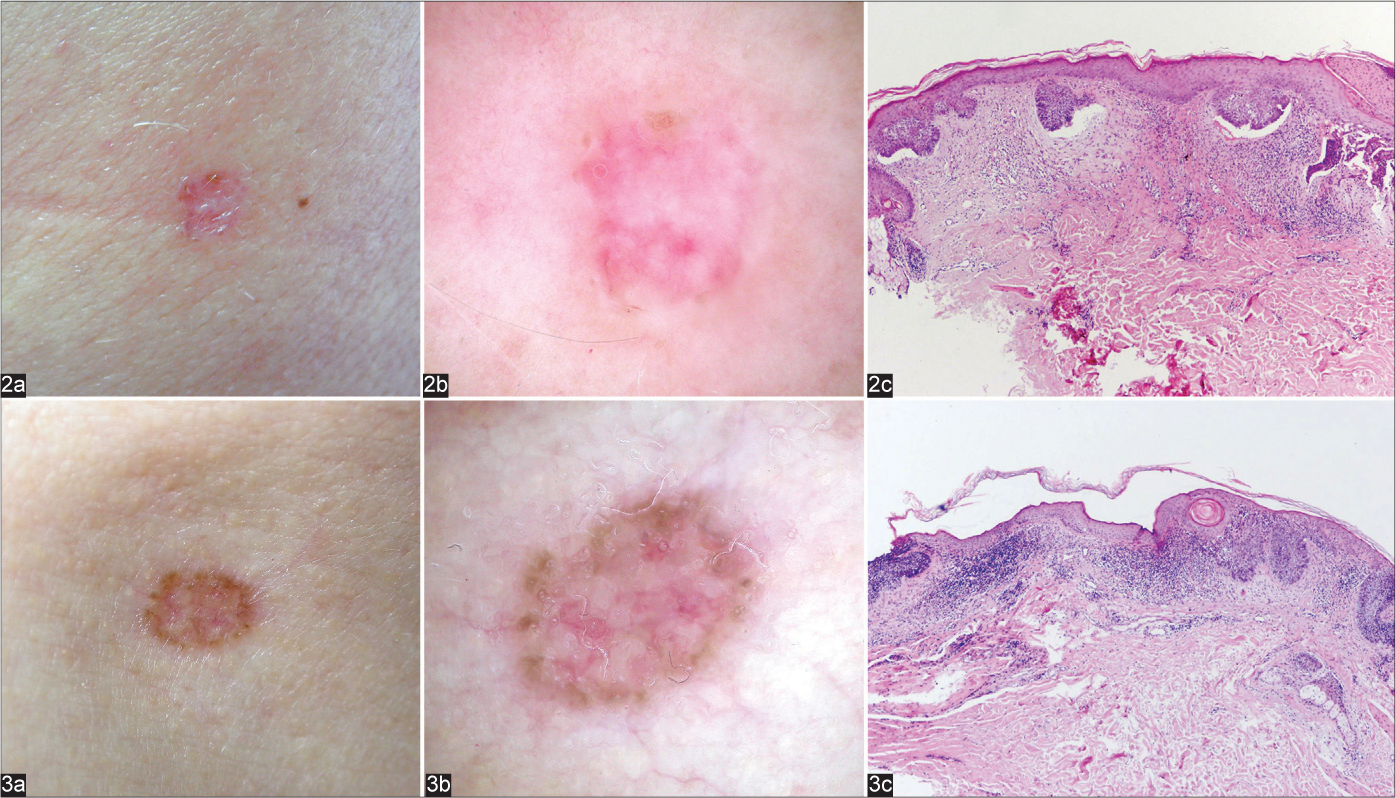

- Superficial basal cell carcinomas with infiltrative clinical presentation (a), absence of typical dermoscopic features for thin basal cell carcinomas (b) with usual histologic presentation (c) haematoxylin and eosin ×40)

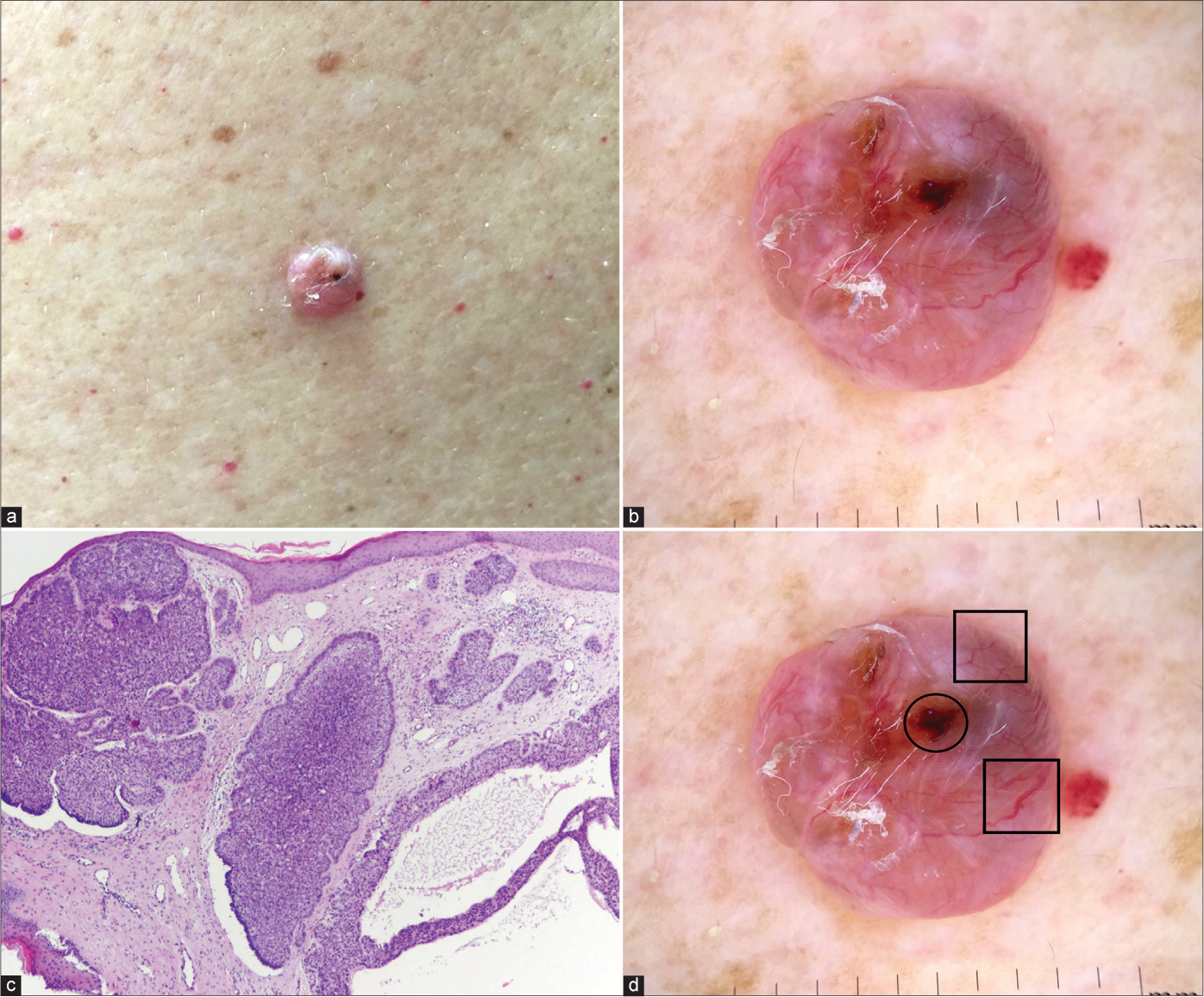

- Nodulocystic basal cell carcinoma with typical clinical (a), dermoscopic (b) and histological (c) presentation (haematoxylin and eosin ×40). Dermoscopic view: blue-grey ovoid nests (circle), arborising and large calibre vessels (squares). (d) Figure 4b with markings

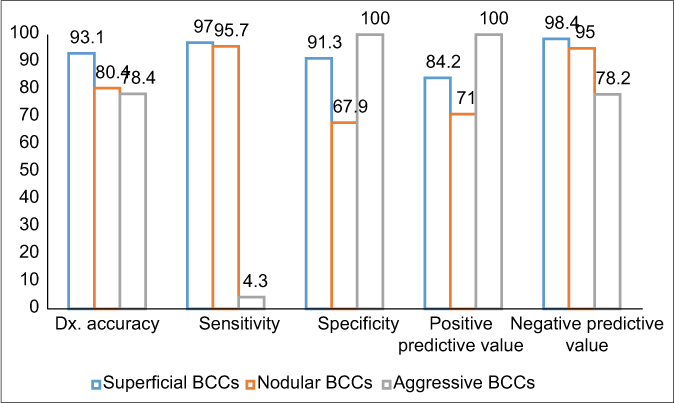

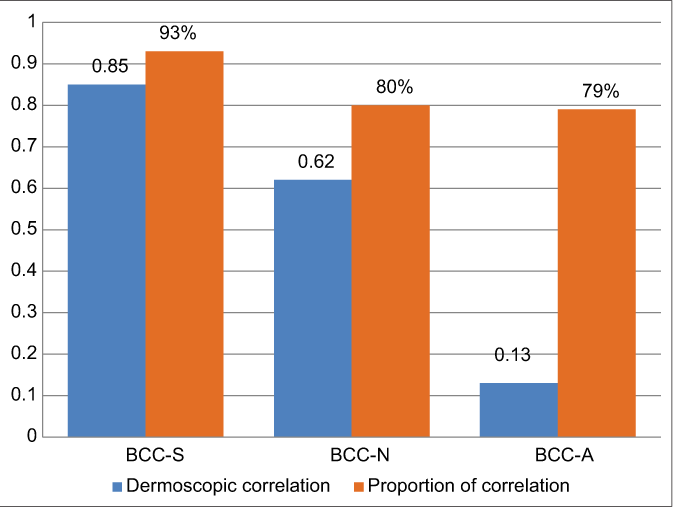

The various measures of diagnostic accuracy for the dermoscopic features of superficial, nodular and aggressive BCCs are shown in Table 3 and Chart 1. The level of agreement between dermatoscopy and histology was excellent in superficial (0.85, CI 95% 0.74–0.96), good in nodular (0.62, CI 95% 0.47–0.77) but low in the aggressive (0.13, CI 95% −0.2–0.4) BCCs. Kappa values and the proportion of dermoscopic correlation with histological diagnosis in superficial, nodular and aggressive BCCs are shown in Chart 2.

| Dermoscopic characteristics | Sn % | Sp % | PPV % | NPV % | Dx accuracy % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superficial BCCs | |||||

| Pigmented characteristics | |||||

| Multiple brown-grey globule | 15.2 | 69.6 | 19.2 | 63.2 | 52.0 |

| Leaf-like pigmentation | 27.3 | 91.3 | 60.0 | 72.4 | 70.6 |

| Spoke-wheel pigmentation | 21.2 | 100 | 100 | 72.6 | 74.5 |

| Brown-grey dots in focus | 36.4 | 82.6 | 50.0 | 73.1 | 67.6 |

| Concentric structures | 27.3 | 92.8 | 64.3 | 72.7 | 71.6 |

| Vascular characteristics | |||||

| Short fine telangiectasias | 54.5 | 97.1 | 90.0 | 81.7 | 83.3 |

| Non-pigmented/non-vascular characteristics | |||||

| Multiple small erosions | 54.5 | 66.7 | 43.9 | 75.4 | 62.7 |

| White-red unstructured areas | 93.9 | 13.0 | 34.1 | 81.8 | 39.2 |

| White short lines | 60.6 | 37.7 | 31.7 | 66.7 | 45.1 |

| Nodular BCCs | |||||

| Pigmented characteristics | |||||

| Large blue-grey ovoid nests | 21.7 | 94.6 | 76.9 | 59.6 | 61.8 |

| Multiple brown-grey globule | 30.4 | 78.6 | 53.8 | 57.9 | 56.9 |

| Leaf-like pigmentation | 8.7 | 80.4 | 26.7 | 51.7 | 48.0 |

| Blue-grey dots in focus | 13.0 | 67.9 | 25.0 | 48.7 | 43.1 |

| Concentric structures | 8.7 | 82.1 | 28.6 | 52.3 | 49.0 |

| Vascular characteristics | |||||

| Arborising vessel | 21.7 | 78.6 | 45.5 | 55.0 | 52.9 |

| Short fine telangiectasias | 2.2 | 66.1 | 5.0 | 45.1 | 37.3 |

| Non-pigmented/non-vascular characteristics | |||||

| Ulceration | 23.9 | 87.5 | 61.1 | 58.3 | 58.8 |

| Multiple small erosions | 28.3 | 50.0 | 31.7 | 45.9 | 40.2 |

| White-red unstructured areas | 89.1 | 10.7 | 45.1 | 54.5 | 46.1 |

| White short lines | 58.7 | 35.7 | 42.9 | 51.3 | 46.1 |

| Aggressive BCCs | |||||

| Pigmented characteristics | |||||

| Large blue-grey ovoid nests | 13.0 | 87.3 | 23.1 | 77.5 | 70.6 |

| Multiple brown-grey globule | 30.4 | 75.9 | 26.9 | 78.9 | 65.7 |

| Leaf-like pigmentation | 8.7 | 83.5 | 13.3 | 75.9 | 66.7 |

| Blue-grey dots in focus | 26.1 | 77.2 | 25.0 | 78.2 | 65.7 |

| Concentric structures | 4.3 | 83.5 | 7.1 | 75.0 | 65.7 |

| Vascular characteristics | |||||

| Arborising vessel | 52.2 | 87.3 | 54.5 | 86.2 | 79.4 |

| Short fine telangiectasias | 4.3 | 75.9 | 5.0 | 73.2 | 59.8 |

| Non-pigmented/non-vascular characteristics | |||||

| Ulceration | 30.4 | 86.1 | 38.9 | 81.0 | 73.5 |

| Multiple small erosions | 43.5 | 60.8 | 24.4 | 78.7 | 56.9 |

| White-red unstructured areas | 82.6 | 8.9 | 20.9 | 63.6 | 25.5 |

| White short lines | 69.6 | 40.5 | 25.4 | 82.1 | 47.1 |

BCC: Basal cell carcinoma, Sn: Sensitivity, Sp: Specificity, PPV: Positive predictive value, NPV: Negative predictive value; Dx: Diagnostic

- Diagnostic accuracy measures of dermoscopic diagnosis for superficial, nodular and aggressive BCCs. BCCs: Basal cell carcinomas, Dx: Diagnostic

- Cohen’s kappa test and proportion of correlation with histology. BCC-S: Superficial basal cell carcinoma, BCC-N: Nodular basal cell carcinoma, BCC-A: Aggressive basal cell carcinoma

Discussion

The value of dermoscopy in distinguishing the histological subtypes of BCC is as yet uncertain. Although some studies have found dermoscopy reliable in classifying the different BCC subtypes,6-8 others have shown it to be of value only in the diagnosis of certain subtypes6,9 and unpredictable in differentiating the aggressive subtypes of BCC.10,11 This may be due to the fact that no single dermoscopic structure is either common to all BCCs or exclusive to a specific BCC subtype.12 Further, the presence of a significant number of mixed BCCs may render dermoscopy unreliable as it visualizes the morphology of the skin up to the middermis but not the deeper tumour islands. In micronodular BCCs, the dense compaction of tiny nodules may be seen dermoscopically as a larger nodule.

Tumour thickness determines the presence of dermoscopic features, but clinical examination cannot reliably distinguish the various histopathologic types of BCC (nodules without irregular infiltrative contours). For example, histopathologically nodular BCCs may present clinically as a minimally raised plaque and not as a nodule. Similarly, micronodular BCCs may be clinically elevated or in the plane of the surrounding skin, depending on the depth in the dermis. Suppa et al. found that increasing palpability of superficial BCCs was associated with an increasing frequency of characteristics typical for nodular BCCs.14

Superficial BCC

The influence of tumour thickness was eliminated by including only thin BCCs in this group. Almost all analysed superficial BCCs had typical clinical [Figure 1a], dermoscopic [Figure 1b] and histological presentation [Figure 1c]. However, 2 (6%) superficial lesions clinically mimicking infiltrative/morpheaform BCC [Figures 2a and 3a] had unusual dermoscopic presentations [Figures 2b and 3b], despite common microscopic features [Figures 2c and 3c].

Leaf-like areas, short fine telangiectasias (SFT), multiple small erosions and white-red structureless areas are strong predictors of superficial BCC and the presence of each of these increases the likelihood of diagnosis by over 5-fold.7 The most robust criteria suggestive of the diagnosis of superficial BCC are the flat surface of the lesion and multiple small erosions.15 Other studies have also confirmed that the presence of multiple small erosions and milky red background increase the likelihood of diagnosis of superficial BCC.16,17 However, in our study the diagnostic accuracy of multiple small erosions for superficial BCC was much lower (62.7%). Further, the diagnostic accuracy of white-red unstructured areas was also low in thin BCCs but short fine telangiectasias had a high diagnostic accuracy (83.3%).

Pigmented structures were also significant in the diagnosis of superficial BCC. Spoke-wheel pigmentation was an exclusive feature of thin BCCs with a diagnostic accuracy of 74.5% and concentric structures and leaf-like pigmentation showed a diagnostic accuracy of 71.6% and 70.6%, respectively.

Overall, the accuracy of dermoscopy for the diagnosis of superficial BCC was high (93.1%) and the agreement of dermoscopic with histologic diagnosis in superficial BCCs was excellent (kappa 0.85, 95% CI 0.74–0.96, proportion of correlation 93%).

Nodular BCCs

Nodular BCC (46 lesions) were the most common histologic type in our study comprising 27 (58.7%) purely nodular and 19 (41.3%, Fig 4) mixed variants (including 11 N-S BCCs). Of the 46 histopathologically nodular BCCs, 5 (10.9%) were clinically categorised as superficial (Fig 5a) and 3 (6.5%) as aggressive BCC (Fig 6a). However, despite the flat clinical morphology, only two of the histopathologically nodular BCCs (Figs 5c and 6c) had dermoscopic features of superficial BCC (Figs 5b and 6b).

- Nodular-superficial basal cell carcinoma with flat and nodular basal cell carcinoma with infiltrative clinical appearance, respectively (a); both cases had typical dermoscopic features (b) of thin tumours, and histopathology of nodular basal cell carcinoma with small superficial component (c, e:arrows ) (Haematoxylin & eosin ×40). Dermoscopic view: erosions (squares), multiple gray globules (circles). (d) Figure 5b and figure 6b with markings. (e) Figure 5c and figure 6c with markings

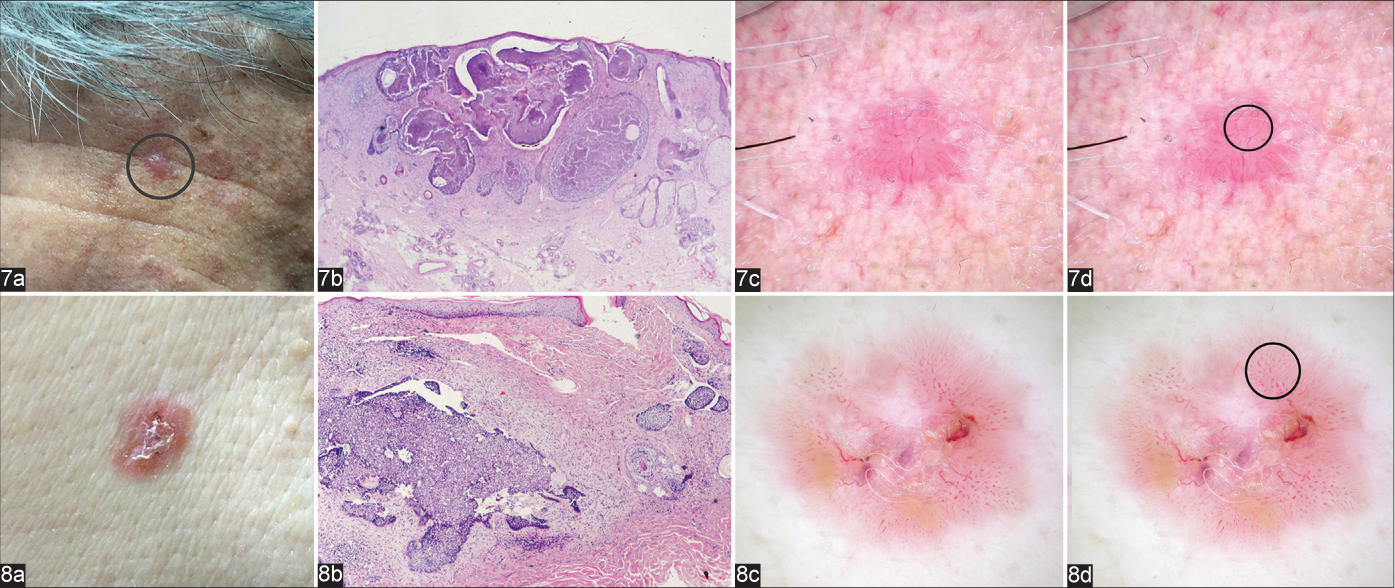

Arborising vessels, blue-grey ovoid nests, multiple blue-grey globules and ulceration are well-known dermoscopic features of nodular BCCs. Arborising vessels are a frequent feature of BCC. Although they are a dermoscopic hallmark of nodular BCC and their presence increases the diagnosis of non-superficial BCCs 11-fold,7 this feature was found in only 10 (21.7%) nodular BCCs in our study and had a low diagnostic accuracy (52.9%). We also frequently found a vascular pattern with dominance of linear, shorter, slightly branched blood vessels [Figure 7c], and polymorphous pattern [Figure 8c].

- Nodular basal cell carcinomas showing typical clinical (a) and microscopic (b) appearance (haematoxylin & eosin ×12.5 and haematoxylin & eosin ×40, respectively); dermoscopic presentation with dominance of linear (Figure 7c, circle), and polymorphous blood vessels (Figure 8c, circle), (d) Figure 7d and Figure 8d with markings)

Blue-grey ovoid nests are a major characteristic of nodular BCC10 and its presence is associated with 15-fold probability of this subtype.7 We found a diagnostic accuracy of 61.8% for blue-grey ovoid nests and they were an important feature in the diagnosis of nodular BCC. The diagnostic accuracy of multiple blue-grey globules was lower (56.9%). The presence of ulceration is associated with a 3-fold greater probability for non-superficial BCCs;7 in our study we noted a diagnostic accuracy of 58.8%.

Thinner variants of nodular BCCs, resulted in lower diagnostic accuracy of dermoscopy for this subtype (80.5%). The agreement of dermoscopic with histologic findings was good 0.62 in nodular BCCs (95% CI 0.47–0.77) with proportion of correlation of 80%.

Aggressive BCCs

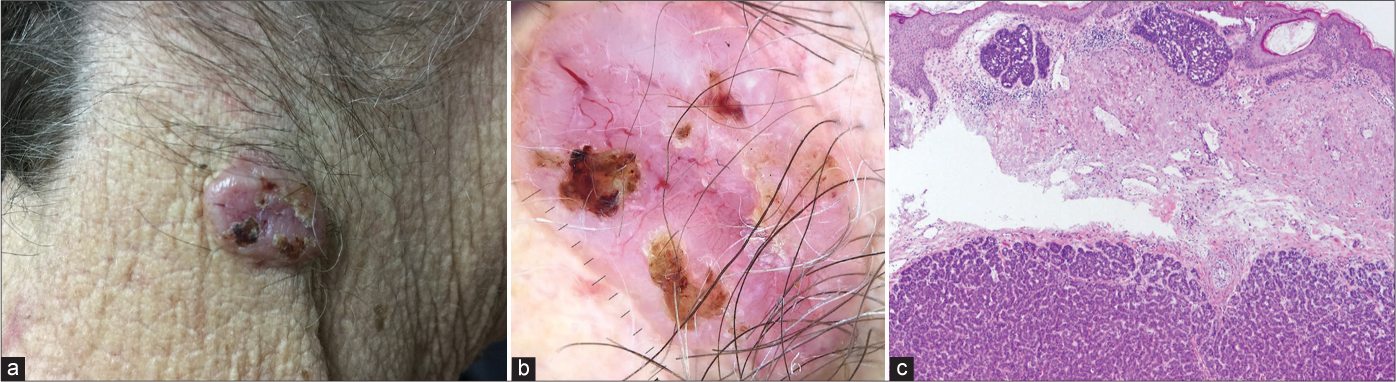

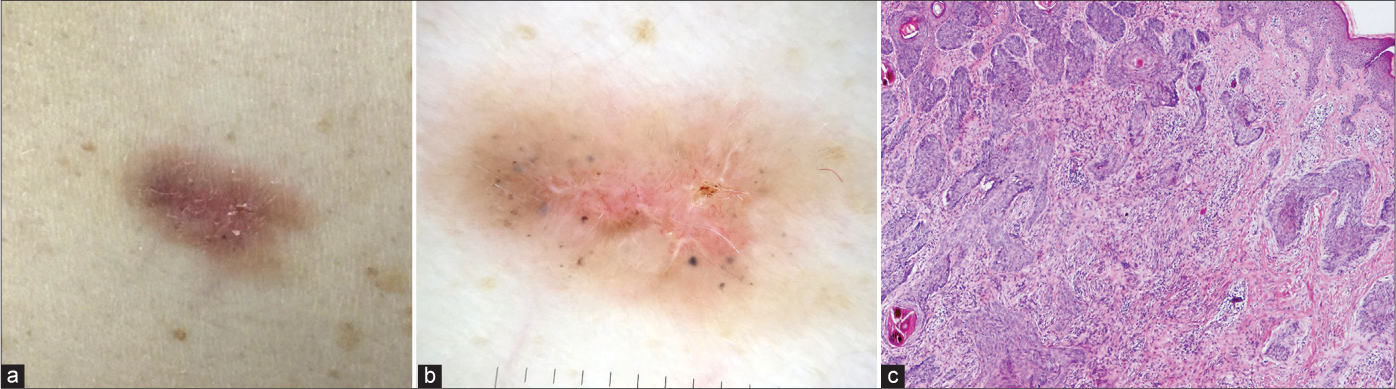

The incidence of aggressive BCCs varies from 2.5% to 44%.11 Although they typically present as depressed, indurated papules or plaques, this was not seen in any of the aggressive BCCs in our study and the majority 19 (82.6%) were nodular both clinically [Figure 9a] and on dermoscopy [Figure 9b]. However, 4 (17.4%) aggressive BCCs mimicked superficial tumours [Figures 10a and b].

- Micronodular basal cell carcinoma showing typical clinical (a) and dermoscopic (b) presentation of nodular basal cell carcinoma; histological features (c) of both, non-aggressive (superficial nodules) and aggressive (deeper micronodular growth pattern) basal cell carcinoma (haematoxylin and eosin ×40)

- Noduloinfiltrative basal cell carcinoma that had typical clinical (a) and dermoscopic (b) presentation of superficial basal cell carcinoma, but with histological features (c) of aggressive basal cell carcinoma type (haematoxylin and eosin ×40)

Earlier studies have not identified any specific dermoscopic feature that would indicate the aggressive nature of BCC.12 Although a predominance short white lines on dermoscopy (a marker of dermal fibrosis) could be expected to associated with aggressive BCCs,18 we found this feature in all three groups of BCCs with a similar diagnostic accuracy (superficial 45.1%, nodular 46.1% and aggressive 47.1%). White-red unstructured areas (representing dermal and tumoural stroma fibrosis) 7 also had a low diagnostic accuracy (25.5%) for aggressive BCCs.

Clinically nodular aggressive BCCs had dermoscopic findings similar to nodular BCC with slight differences in diagnostic values. However, aggressive BCCs were characterised by more subtle arborising vessels with less pronounced ramifications, scattered on a whitish-pink background as compared to those seen in nodular BCCs.

Subtle arborising vessels were present in 12 (52.2%) aggressive BCCs in our study and showed the highest value (79.4%), and the best ratio between Sn (52.2%), Sp (87.3%) and PPV (54.5%) for the diagnosis of this subtype.

Verduzco-Martine z et al. concluded that the joint presence of arborising vessels and ulceration suggests a diagnosis of BCC with a higher risk of local recurrence.9 In our study subtle arborising vessels were highly predictive of aggressive BCCs (diagnostic accuracy 79.4%, Sp (84%). Although infiltrative/morpheaform BCCs rarely develop ulceration, this feature was sigificantly associated with aggressive BCCs (Sn 50%, Sp 83% and PPV 98%).10 We found a diagnostic accuracy of 73.5% for ulceration confirming its importance in diagnosis of aggressive BCCs.

Infiltrative/morpheaform BCCs are rarely clinically pigmented. Lallas et al. has listed ulceration and blue-grey ovoid nests as criteria for infiltrative/morpheaform BCCs, while another study describes the presence of blue-grey ovoid nests, multiple blue-grey dots and in-focus dots in infiltrative BCCs.17,19 In our study blue-grey ovoid nests were the most often associated with aggressive BCC showing the accuracy of 70.6%, while leaf-like pigmentation and multiple blue-grey globules displayed an accuracy of 66.7% and 65.7%, respectively.

The accuracy of dermoscopic diagnosis for aggressive BCCs was lower (78.4%) than for nodular BCCs and agreement of dermoscopic with histological diagnosis was low (kappa 0.13, 95% CI −0.20–0.40, agreement proportion 79%).

Limitations

The limitations of our study include the fact that it was a retrospective analysis, that it was conducted in a single medical centre and that all patients studied were Caucasians.

Conclusion

Various combinations of SFT, spoke-wheel pigmentation, concentric structures and maple leaf-like pigmentation give the most accurate correlation with histopathologic diagnosis of the superficial BCCs. Dermoscopy does not accurately correlate with histopathology in aggressive BCCs. Arborising vessels mixed with ulceration, and blue-grey ovoid nests are more suggestive of nodular BCC but do not rule out the aggressive BCC.

Declaration of patient consent

The patients' consent is not required as the patients' identities are not disclosed or compromised.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tumors of the skin In: Damjanov I, Fan F, eds. Cancer Grading Manual (1st ed). New York: Springer Science, Business Media LLC; 2007. p. :99-100.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Mohs micrographic surgery for basal cell carcinomas: Appropriateness of “Rotterdam” criteria and predictive factors for three or more stages. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1228-35.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Histology-based treatment of basal cell carcinoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2009;89:454-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agreement between histological subtype on punch biopsy and surgical excision in primary basal cell carcinoma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:894-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- British association of dermatologist for the management of adults with basal cell carcinoma 2021. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:899-920.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Accuracy of dermoscopic criteria for discriminating superficial from other subtypes of basal cell carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;70:303-11.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The relation between dermoscopy and histopathology of basal cell carcinoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90:351-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Classifying distinct basal cell carcinoma subtype by means of dermatoscopy and reflectance confocal microscopy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:716-24.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Correlation of dermoscopic findings with histopathologic variants of basal cell carcinoma. Int J Dermatol. 2013;52:718-21.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sclerodermiform basal cell carcinoma: How much can we rely on dermatoscopy to differentiate from non-aggressive basal cell carcinomas? Analysis of 1256 cases. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:229-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermoscopic features in different morphologic types of basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Surg. 2014;40:725-32.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dermoscopic features of basal cell carcinoma and its subtypes: A systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;S0190-9622:33008-7.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dermoscopic variability of basal cell carcinoma according to clinical type and anatomic location. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:1732-41.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preoperative prediction of histopathological outcome in basal cell carcinoma: Flat surface and multiple small erosions predict superficial basal cell carcinoma in lighter skin types. Br J Dermatol. 2016;175:751-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermoscopy of basal cell carcinoma. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2018;43:241-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The dermatoscopic universe of basal cell carcinoma. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2014;4:11-24.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiny white streaks: A sign of malignancy at dermoscopy of pigmented skin lesions. Acta Derm Venereol. 2014;94:132-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- How to diagnose non-pigmented skin tumors: A review of vascular structures seen with dermoscopy: Part II. Nonmelanocytic skin tumors. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:377-86. quiz 87-8

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]