Translate this page into:

Tofacitinib treatment for plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials

Corresponding authors: Dr. Yanfang Zhou, Department of Basic Medical Sciences, Guangdong Medical University, Dongguan, Guangdong, China. yfzhou@gdmu.edu.cn.

Dr. Xiaoyan Cheng, Department of Traditional Chinese Medicine, The Second Clinical Medical College, Guangdong Medical University, Dongguan, Guangdong, China. chengxiaoyan@gdmu.edu.cn.

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Wang T, Wu W, Zhang X, Gan B, Zhou Y, Cheng X. Tofacitinib treatment for plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2025;91:172-9. doi: 10.25259/IJDVL_14_2024

Abstract

Objectives

Tofacitinib is used as an oral Janus-associated kinase (JAK) inhibitor acting on JAK1 and JAK3, in treating psoriatic disease. However, there is still no consensus on the optimal dosage and duration of tofacitinib. In this study, we aimed to evaluate the effects of tofacitinib in treating psoriatic disease.

Methods

A literature search was done utilising Cochrane library, Medline, EMBASE, Wiley Online library, Web of Science and BIOSIS Previews through December 18, 2022. We performed a meta-analysis of published original studies to assess the impact of tofacitinib in plaque psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis therapy based on seven randomised controlled trials (RCTs) involving 2,672 patients (receiving tofacitinib) and 853 controls (receiving placebo).

Results

Compared with placebo, the treatment of 5 mg twice-daily (BID) tofacitinib for 12 weeks is sufficient to significantly alleviate the main clinical manifestations of psoriasis [≥75% decrease in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score (PASI 75): Risk ratio (RR)=4.38 (95% Confidence interval (CI) 2.51 to 7.64); ≥90% decrease in PASI score (PASI 90): RR=21.68 (95% CI 4.20 to 111.85); Physician’s Global Assessment of ‘clear’ or ‘almost clear’ (PGA 0/1): RR=3.93 (95%CI 3.03 to 5.09)]. Interestingly, there was no significant difference in improvement in PGA 0/1 with 5 mg BID tofacitinib given for 16 weeks when compared with 5 mg BID tofacitinib for 12 weeks [RR=1.11 (95%CI 0.98 to 1.25)]. Additionally, the 5 mg BID tofacitinib for 16 weeks treatment schedule significantly increased the incidence of upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) [RR=1.89 (95%CI 1.06 to 3.38)] as compared to 5 mg BID tofacitinib for 12 weeks treatment schedule [RR=1.15 (95%CI 0.60 to 2.20)].

Conclusion

The 5 mg BID tofacitinib for 12 weeks treatment significantly improved psoriasis without causing too many specific adverse events. This indicated that tofacitinib is an effective treatment plan for psoriatic disease by reasonably controlling dosage and dosing time.

Keywords

Adverse drug events

efficacy

plaque psoriasis

psoriatic arthritis

tofacitinib

Introduction

Psoriasis is an immune-mediated chronic disease with varying clinical manifestations, affecting approximately 2% of the population.1–3 Psoriasis may have serious disease comorbidities, while also tremendously reducing the quality of life for patients.4,5 Many psoriasis patients have localised disease, in which topical therapy can serve as the cornerstone of treatment.6 Mild or localised psoriasis can be treated through topical treatments, while more severe or widespread psoriasis requires systemic or biological therapies.7,8

Plaque psoriasis is a common manifestation of psoriasis, accounting for approximately 80% of cases. It generally occurs in the scalp and torso, presenting as obvious erythematous lesions with thick layers of silvery-white scales on the surface.9,10 Plaque psoriasis may be accompanied by symptoms such as itching, dry skin, pain, scaling and punctate bleeding. Although it cannot be cured, active treatment can effectively control symptoms and even achieve clinical cure. If not actively treated, it may develop into pustular psoriasis or erythrodermic psoriasis.11,12

In addition to plaque psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis is another major clinical manifestation of psoriatic disease. It involves painful inflammation of joints and surrounding connective tissue.13,14 Psoriatic arthritis usually affects the fingers and toes, causing them to swell into a sausage-like shape, a condition known as dactylitis. Other joints may also be affected, such as the knees, buttocks, the sacroiliac joint, and the spine.15,16 About one-third of psoriasis patients will develop psoriatic arthritis, a seronegative arthritis related to psoriasis.17 Seventy-five per cent of psoriasis patients showed dermatologic manifestations of the disease before arthritic manifestations.18–20

Tofacitinib is an oral medication that can regulate immune response by reversibly inhibiting the activity of Janus-associated kinases (JAK) 1 and 3.21–24 JAK is a family of non-receptor tyrosine kinases that can phosphorylate proteins. The signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) protein, a substrate of JAK, undergoes dimerisation after being phosphorylated by JAK and then enters the nucleus to regulate the expression of related genes. The JAK-STAT pathway is involved in processes such as immunity, cell death and tumour formation.25–28 As a JAK inhibitor, tofacitinib was first approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in November 2012 for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis which is an immune-mediated disease.29–31 In addition, it was found that the inhibition of JAK3 can significantly reduce psoriasiform inflammation (another autoimmune disease) in mice.32 Therefore, due to the similarities between mice and human psoriasis, tofacitinib is also speculated to be able to treat human psoriasis by targeting JAK3 to block the signalling of cytokines. Subsequently, some randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have been conducted to investigate the effects of tofacitinib in treating patients with plaque psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis.33–35 However, the relative optimal treatment plan for tofacitinib in the treatment of psoriasis patients has not been clarified. The aim of this study is to systematically analyse the therapeutic effects of different treatment regimens of tofacitinib on patients with plaque psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis.

Methods

Searching strategy and eligibility of relevant studies

We searched all relevant studies published prior to December 18, 2022, in literature databases including Cochrane library, Medline, EMBASE, Wiley Online library, Web of Science, and BIOSIS Previews. The following keywords were used for searching: ‘plaque psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis’ and ‘tofacitinib/CP690550’ [Supplementary Table 1]. Only the RCT studys that met the following conditions were included: the efficacy or safety of tofacitinib was evaluated in the treatment of plaque psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis; the study provided raw and detailed data information for meta-analysis. For the primary outcomes, the candidate RCT research should include at least one of the following commonly used indicators: the proportion of participants achieving ≥75% decrease in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score (PASI 75), ≥90% decrease in the PASI score (PASI 90) or a Physician’s Global Assessment of ‘clear’ or ‘almost clear’ (PGA 0/1) by 12–16 weeks. Also, we examined specific adverse events commonly reported in the RCTs including nasopharyngitis, hypercholesterolemia, headache, upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) and creatinine phosphokinase (CPK) elevation. In addition to the database search, we also checked references listed on the identified articles for potentially eligible reports. The PRISMA guidelines were used for reporting the meta-analysis [Supplementary Tables 2 and 3].

Data extraction

All related studies were original experimental articles which we evaluated based on the reporting. The included studies had to meet all of the following criteria: studies should have (1) detailed patient information; (2) information about disease type and (3) explored the therapeutic effect of tofacitinib in the treatment of plaque psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. The exclusion criteria were (1) meta-analysis papers, review papers, conference papers, abstracts, theses and reports; (2) non-human tissue data; (3) papers lacking raw data; (4) post hoc studies of the same primary research; and (5) non-English papers. The extracted data included clinical trial number, ethnicity, type of clinical manifestations, diagnostic time, follow-up period, dosage of tofacitinib, frequency of taking medicine, measures of efficacy, measures of safety, number of patients and controls, and number of treatment outcomes. Two independent reviewer authors screened the articles. The disputes among the reviewers were settled by a third review author or discussion.36

Statistical analysis

For the extracted data, the meta package in R software (version 4.1.0) was used to perform the meta-analysis by generating the risk ratio (RR) with a 95% confidence interval (CI).37 In addition to comparing the pooled effects among all subjects, we also conducted stratified comparisons according to the dosage (5 mg and 10 mg), the dosing time (12 weeks and 16 weeks) and the clinical manifestation types of psoriatic disease (plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis). The main results of the meta-analysis were presented by the forest plots.38 The heterogeneity among studies was measured by the Mantel-Haenszel method.39 The quantitative results of I2 statistic were showed in the forest plots. A random effects model was conducted to estimate the pooled RR, when there was a significant heterogeneity (P < 0.05, I2 > 50%). Otherwise, the common effect model was performed.40 In addition, Labbe plot was used to visually and qualitatively present the heterogeneity. The robustness and reliability of the combined results were evaluated by the sensitivity analysis. The results of sensitivity analysis were presented using forest plots. Potential publication bias was analysed by Egger’s test.41,42 The results of publication bias were presented using funnel plots.43 The GRADE system was used to evaluate the outcome indicators. When the P value is less than 0.05, it indicates that the result is statistically significant.

Results

Data selection and characteristics of eligible research

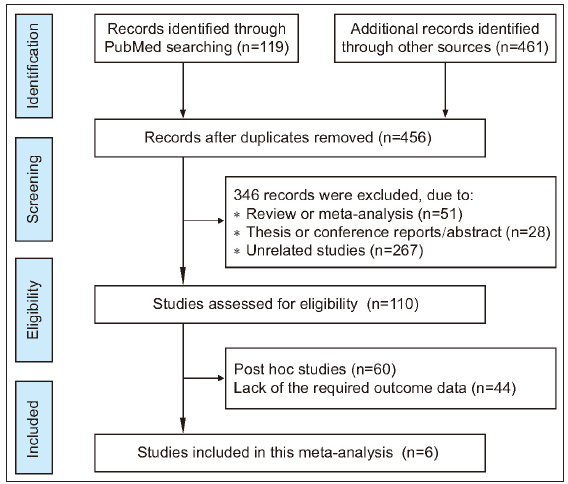

Based on the search terms, we retrieved 580 articles. During a brief review of the title and abstract of each article, 124 articles were discarded as duplicate studies. After a more careful inspection of the abstracts, 346 papers that were reviews, conference reports, or irrelevant studies were removed. Of the remaining 110 studies, 60 papers were post hoc analysis, and 44 did not have the required outcome data. Only six papers (seven clinical trial studies) were ultimately considered in the meta-analysis which met the screening requirements. Of the seven clinical trials, two different types of diseases with 2,672 patients receiving tofacitinib treatment and 853 receiving placebo were analysed in meta-analysis. Figure 1 showed the workflow for study selection. All seven clinical trials were double-blinded, with a low risk of bias [analysed by RoB 2.0, Supplementary Figure 1].33,44–48 The main characteristics of each study were shown in Supplementary Tables 4–6. In addition, a summary of findings table created by the GRADE system showed that the quality of evidence for outcome indicator was high or moderate [Supplementary Table 7].

- Flowchart of the strategy used for the selection of studies used in the meta-analysis.

Based on the measures of efficacy or safety for the tofacitinib treatment, the heterogeneity analyses were performed separately. In meta-analysis, we conducted stratified sub-analyses on different dosages (10 mg or 5 mg) and dosing time (12 weeks or 16 weeks) for tofacitinib to reduce the heterogeneity [Supplementary Figures 2a-b]. The significant heterogeneity was only observed in PASI 75 and nasopharyngitis subgroups (PASI 75 with 5 mg BID tofacitinib for 12 weeks: I2 = 70, P < 0.01; PASI 75 with 10 mg BID tofacitinib for 12 weeks: I2 = 75, P < 0.01; nasopharyngitis with 5 mg BID tofacitinib for 16 weeks: I2 = 78, P = 0.01) which caused discrete points in the Labbe plots and may arise from the ethnicity or other factors.

Efficacy of tofacitinib in achieving PASI 75, PASI 90, or PGA 0/1

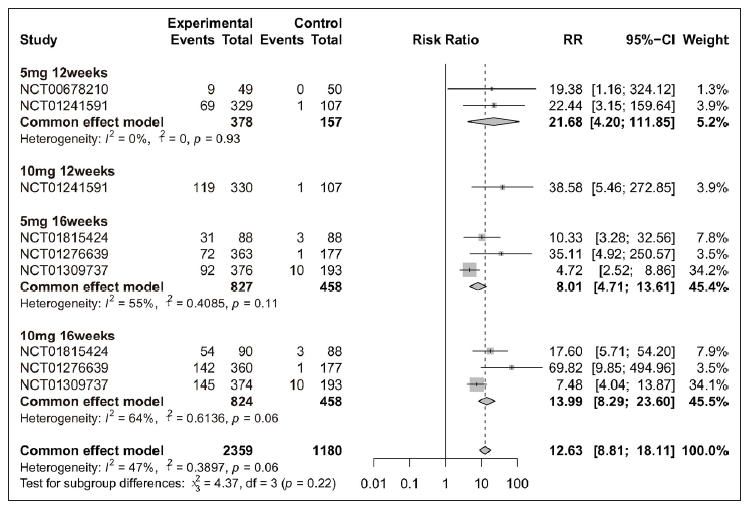

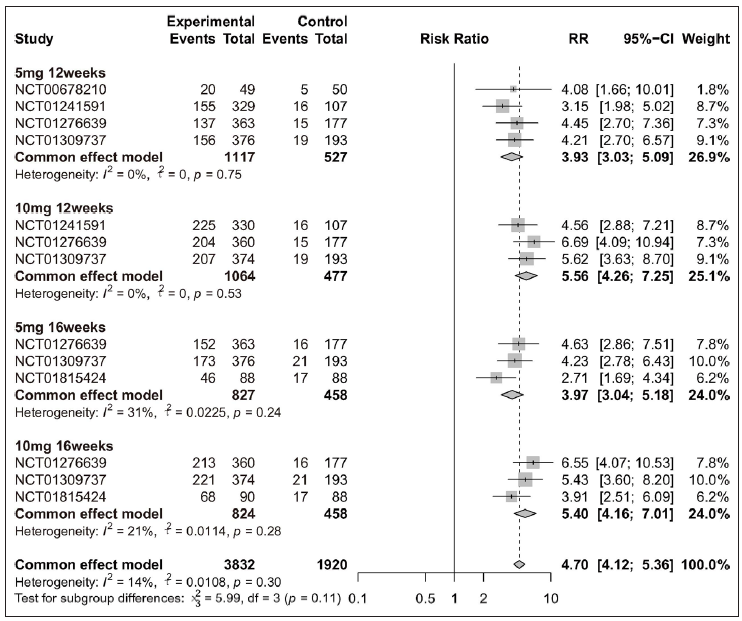

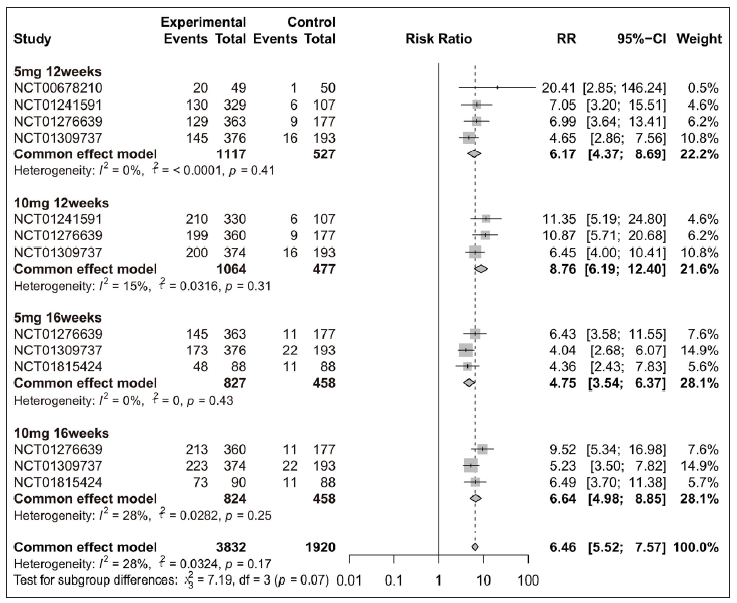

Overall, patients receiving tofacitinib treatment had a better response for PASI 90 [RR = 12.63 (95% CI 8.81 to 18.11), Figure 2] and PGA 0/1 [RR = 4.70 (95% CI 4.12 to 5.36), Figure 3] as compared with placebo. When patients were separated by four different treatment plans of tofacitinib (5 mg 12 weeks, 10 mg 12 weeks, 5 mg 16 weeks, and 10 mg 16 weeks), significant improvements were still observed in each subgroup for PASI 75 [Supplementary Figure 3a], PASI 90 [Figure 2], and PGA 0/1 [Figure 3] when compared with placebo. Interestingly, there was no significant improvement observed in PGA 0/1 for 5 mg 16 weeks tofacitinib treatment when compared with 5 mg 12 weeks tofacitinib treatment plan [Supplementary Figure 3b].

- Efficacy analysis of tofacitinib compared with placebo by different treatment plans (5 mg 12 weeks, 10 mg 12 weeks, 5 mg 16 weeks and 10 mg 16 weeks) for patients achieving ≥ 90% reduction in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score (PASI 90).

- Efficacy analysis of tofacitinib compared with placebo by different treatment plans (5 mg 12 weeks, 10 mg 12 weeks, 5 mg 16 weeks and 10 mg 16 weeks) for patients achieving Physician’s Global Assessment of ‘clear’ or ‘almost clear’ (PGA 0/1).

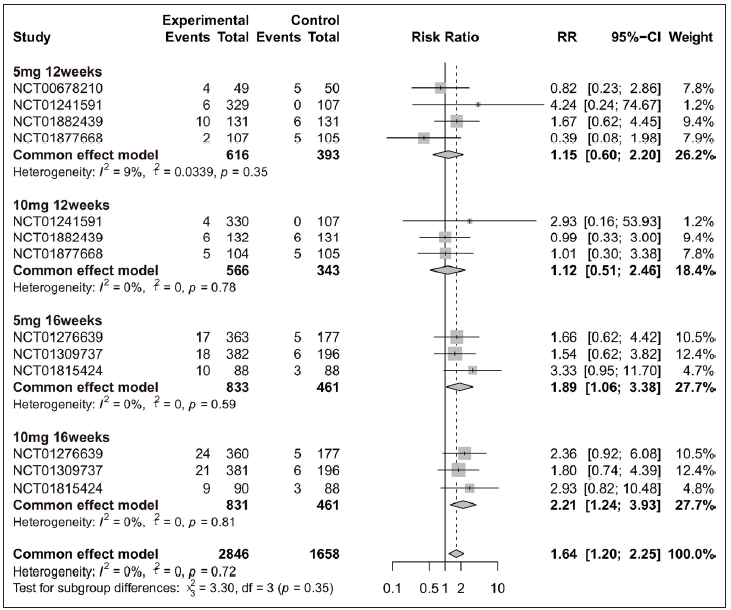

Specific adverse events about URTI, hypercholesterolemia, CPK elevation, headache, and nasopharyngitis

Overall, four adverse events (URTI, hypercholesterolemia, CPK elevation, and headache) exhibited higher incidence rate in the tofacitinib group when compared with placebo [Figure 4 and Supplementary Figure 4]. When patients were separated by four different treatment plans, significant differences were only observed in the 16 weeks tofacitinib-treated groups for URTI [5 mg 16 weeks and 10 mg 16 weeks, Figure 4], hypercholesterolemia [5 mg 16 weeks and 10 mg 16 weeks, Supplementary Figure 4a], CPK elevation [10 mg 16 weeks, Supplementary Figure 4b], and headache [10 mg 16 weeks, Supplementary Figure 4c]. For nasopharyngitis, there was no significant difference between tofacitinib and placebo group [Supplementary Figures 5a-5d]. In addition, 10 mg tofacitinib appeared to induce higher incidence of adverse events when compared with 5 mg tofacitinib treatment, especially for CPK elevation [Supplementary Figure 6].

- Safety analysis of tofacitinib compared with placebo by different treatment plans (5 mg 12 weeks, 10 mg 12 weeks, 5 mg 16 weeks and 10 mg 16 weeks) for upper respiratory tract infection (URTI).

Tofacitinib treatment in plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis

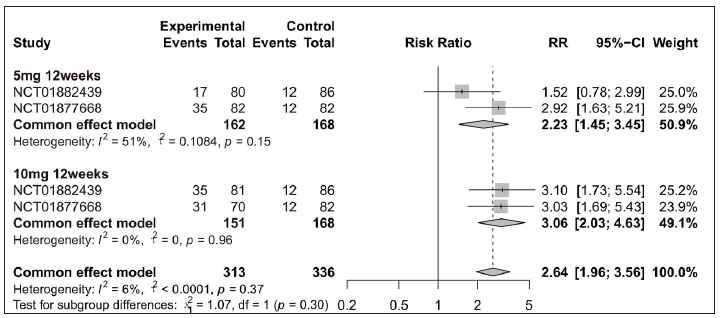

Amongst efficacy or safety indicators for tofacitinib treatment, five were measured for both plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: PASI 75, URTI, CPK elevation, headache, and nasopharyngitis. To explore the impact of tofacitinib treatment on these two clinical manifestations of psoriasis, stratified sub-analyses were performed for those indicators. Overall, the significant differences were observed in tofacitinib group for PASI 75 in plaque psoriasis [Figure 5a] and in psoriatic arthritis [Figure 5b], for URTI in plaque psoriasis [Supplementary Figure 7a], for CPK elevation in plaque psoriasis [Supplementary Figure 7b], for headache in plaque psoriasis [Supplementary Figure 8a], and for nasopharyngitis in psoriatic arthritis [Supplementary Figure 8b] when compared with the placebo group. Additionally, when patients were separated by four different treatment plans, significant differences were still observed in each tofacitinib-treated subgroup for PASI 75 in plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis [Figure 5].

- Efficacy analysis of tofacitinib compared with placebo by different treatment plans for patients achieving ≥ 75% reduction in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score (PASI 75) in each clinical manifestation of psoriatic disease. (a) Forest plot of plaque psoriasis in four subgroups (5 mg 12 weeks, 10 mg 12 weeks, 5 mg 16 weeks and 10 mg 16 weeks).

- Efficacy analysis of tofacitinib compared with placebo by different treatment plans for patients achieving ≥ 75% reduction in the Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score (PASI 75) in each clinical manifestation of psoriatic disease. (b) Forest plot of psoriatic arthritis in two subgroups (5 mg 12 weeks, 10 mg 12 weeks).

Sensitivity and publication bias analyses

Overall, the results of sensitivity analyses [Supplementary Figures 9a-g] showed that the exclusion of any individual study did not change the significance of the RRs for PASI 75 (5 mg 12 weeks, 10 mg 12 weeks, 5 mg 16 weeks, and 10 mg 16 weeks), PASI 90 (5 mg 16 weeks, 10 mg 16 weeks), PGA 0/1 (5 mg 12 weeks, 10 mg 12 weeks, 5 mg 16 weeks, and 10 mg 16 weeks), URTI (5 mg 16 weeks, 10 mg 16 weeks), and hypercholesterolemia (5 mg 16 weeks, 10 mg 16 weeks). It indicated that these pooled RRs of meta-analysis were reliable. The sensitivity result of nasopharyngitis was consistent with its Labbe plot [Supplemental Figure 2] which indicated that heterogeneity existed in this dataset.

In addition, publication bias was conducted for efficacy and safety indicators. Based on Egger’s test, there was no publication bias for PASI 75 (5 mg 12 weeks, 10 mg 12 weeks, 5 mg 16 weeks, and 10 mg 16 weeks), PASI 90 (5 mg 16 weeks, 10 mg 16 weeks), PGA 0/1 (5 mg 12 weeks, 10 mg 12 weeks, 5 mg 16 weeks, and 10 mg 16 weeks), URTI (5 mg 12 weeks, 10 mg 12 weeks, and 10 mg 16 weeks), hypercholesterolemia (5 mg 16 weeks, 10 mg 16 weeks), and nasopharyngitis (5 mg 12 weeks, 10 mg 12 weeks, 5 mg 16 weeks, and 10 mg 16 weeks) which didn’t show obvious asymmetry in the funnel plot [Supplementary Figures 10a-b].

Discussion

The JAK-STAT signal transduction pathway enables key cytokines to function and is closely related to pathophysiological processes. Nevertheless, tofacitinib acts as an inhibitor of JAK1 and JAK3 which means that it targets the intracellular JAK-STAT signalling pathway and inhibits phosphorylation of the STAT by preventing JAK phosphorylation.49–51 Today, multiple immune diseases are treated with tofacitinib such as inflammatory bowel disease,52 renal transplant rejection53 and active rheumatoid arthritis.54 In this study, meta-analysis indicated that both 5 mg and 10 mg BID regimens of tofacitinib are effective in treating psoriatic disease, consistent with the RCTs44–48 where tofacitinib significantly improved plaque psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis compared with placebo.

Furthermore, 10 mg BID tofacitinib was found to be more effective than 5 mg BID tofacitinib in treating psoriatic disease based on the PASI 75, PASI 90 or PGA 0/1 in our meta-analysis. These were consistent with previous studies34,44 which showed that the proportion of psoriasis patients treated with 10 mg BID tofacitinib achieving improvement is higher than that of psoriasis patients treated with 5 mg BID tofacitinib, whereas many adverse events showed significant higher incidence rates in 10 mg BID group (CPK elevation: 4.8% versus 1.7%; headaches: 6.3% versus 3.6%; URTI: 4.9% versus 3.1%, etc.) when compared with placebo. In addition, 10 mg BID tofacitinib appeared to induce more CPK elevation events compared with 5 mg BID tofacitinib (4.9% versus 3.0%). All these evidences support that 5 mg of tofacitinib BID is an appropriate dosage for treatment of plaque psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis patients.

Significant efficacy of tofacitinib was observed at both follow-up end points (12 weeks or 16 weeks) in treating plaque psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. Although 16 weeks treatment was shown to be more effective than 12 weeks, significant increased adverse events specifically were observed. In addition, compared with other treatment plans (16 weeks with 5 mg BID, 12 weeks with 10 mg BID, and 16 weeks with 10 mg BID), the 5 mg BID tofacitinib for 12 weeks treatment is sufficient to significantly reduce disease symptoms without causing too many adverse events. Overall, our meta-analysis indicated that 5 mg BID of tofacitinib treatment for 12 weeks is the likely best treatment for psoriatic disease. For subgroup analysis of plaque psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis, our results showed that tofacitinib exhibits significant efficacy in treating both clinical manifestations of psoriatic disease.

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, due to the limited variables explored in the included RCTs, the current study has not been registered and low levels of heterogeneity in some subgroup analyses cannot be explained. Secondly, the number of trials included in the subgroup analysis is limited which may be related to the fact that not all the efficacy and safety indicators were explored in each included RCT. Finally, more RCTs are needed to confirm our meta-analysis.

Conclusion

In our study, meta-analysis revealed that 5 mg of tofacitinib BID is an appropriate dosage in treating plaque psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis patients. More doses or longer duration of tofacitinib was shown to significantly increase adverse events. Therefore, 5 mg tofacitinib BID for 12 weeks is the recommended treatment for the two main clinical manifestations of psoriatic disease. Taken together, these results indicated that tofacitinib is a reasonable treatment option for psoriatic disease by reasonably controlling the dosage and dosing time. Further research in a larger number of psoriatic patients is required to explore the relative efficacy or safety of tofacitinib treatment.

Declaration of patient consent

Patient’s consent not required as there are no patients in this study.

Financial support and sponsorship

This study was supported by the open research fund of Songshan Lake Materials Laboratory (2023SLABFN21), Guangdong Medical Science and Technology Research Found Project (A2020353, A2021154), the Foshan City’s ‘14th Five Year Plan’ that cultivates key medical specialties–Sexual Medicine Department and the Foshan City’s ‘14th Five Year Plan’ Traditional Chinese Medicine Specialised Disease Cultivation Project–Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine Bone Bi and the grant from the Guangdong Medical University Doctoral Initiation Project, grant number: GDMUB2022029 (4SG23239G).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

References

- Psoriasis: Genetic associations and immune system changes. Genes Immun. 2007;8:1-12.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The psychosocial burden of psoriatic arthritis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2017;47:351-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The psychosocial burden of psoriasis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2005;6:383-92.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topical therapies for the treatment of plaque psoriasis: Systematic review and network meta-analyses. Br J Dermatol. 2013;168:954-67.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Section 1. Overview of psoriasis and guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis with biologics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:826-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Combining biologic therapies with other systemic treatments in psoriasis: Evidence-based, best-practice recommendations from the medical board of the national psoriasis foundation. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:432-38.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis and classification of psoriasis. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13:490-95.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Immunological memory of psoriatic lesions. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:625.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Undertreatment, treatment trends, and treatment dissatisfaction among patients with psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis in the United States: Findings from the national psoriasis foundation surveys, 2003-2011. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149:1180-85.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Section 6. Guidelines of care for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Case-based presentations and evidence-based conclusions. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65:137-74.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Time trends in epidemiology and characteristics of psoriatic arthritis over 3 decades: A population-based study. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:361-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Physician perspectives in the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: Results from the population-based multinational assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis survey. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2015;29:2002-10.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The pathogenesis of psoriatic arthritis. Lancet. 2018;391:2273-84.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Targeted systemic therapies for psoriatic arthritis: A systematic review and comparative synthesis of short-term articular, dermatological, enthesitis and dactylitis outcomes. RMD Open. 2022;8:e002074.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Group for research and assessment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis 2015 treatment recommendations for psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2016;68:1060-71.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAK inhibitors, psoriatic arthritis, and axial spondyloarthritis: A critical review of clinical trials. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2021;17:701-15.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The JAK inhibitor tofacitinib suppresses synovial JAK1-STAT signalling in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2015;74:1311-16.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical significance of janus kinase inhibitor selectivity. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58:953-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- The JAK1/3 inhibitor tofacitinib suppresses T cell homing and activation in chronic intestinal inflammation. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;15:244-57.

- [Google Scholar]

- The molecular details of cytokine signaling via the JAK/STAT pathway. Protein Sci. 2018;27:1984-09.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- JAK/STAT pathway and nociceptive cytokine signalling in rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2021;39:668-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAK-STAT pathway targeting for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:323-37.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- JAK-STAT signaling as a target for inflammatory and autoimmune diseases: Current and future prospects. Drugs. 2017;77:521-46.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Placebo-controlled trial of tofacitinib monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:495-07.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:508-19.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofacitinib: A review in rheumatoid arthritis. Drugs. 2017;77:1987-01.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAK3 inhibition significantly attenuates psoriasiform skin inflammation in CD18 mutant PL/J mice. J Immunol. 2009;183:2183-92.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofacitinib or adalimumab versus placebo for psoriatic arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1537-50.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib for moderate-to-severe plaque psoriasis: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2018;32:355-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofacitinib for the treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018;14:719-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- How to do a systematic review: A best practice guide for conducting and reporting narrative reviews, meta-analyses, and meta-syntheses. Annu Rev Psychol. 2019;70:747-70.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Intervention meta-analysis: Application and practice using R software. Epidemiol Health. 2019;41:e2019008.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Understanding the basics of meta-analysis and how to read a forest plot: As simple as it gets. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81:20f13698.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estimating risk and rate ratio in rare events meta-analysis with the mantel-haenszel estimator and assessing heterogeneity. Int J Biostat 2022:21-38.

- [Google Scholar]

- Key concepts in clinical epidemiology: Detecting and dealing with heterogeneity in meta-analyses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021;130:149-51.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Publication bias in meta-analysis: Its causes and consequences. J Clin Epidemiol. 2000;53:207-16.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. Bmj. 1997;315:629-34.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. Bmj. 2011;343:d4002.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofacitinib, an oral Janus kinase inhibitor, for the treatment of chronic plaque psoriasis: Results from two randomized, placebo-controlled, phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:949-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofacitinib versus etanercept or placebo in moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis: A phase 3 randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2015;386:552-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy and safety of tofacitinib, an oral janus kinase inhibitor, in the treatment of psoriasis: A phase 2b randomized placebo-controlled dose-ranging study. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:668-77.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The efficacy and safety of tofacitinib in Asian patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis: A phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Dermatol Sci. 2017;88:36-45.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofacitinib for psoriatic arthritis in patients with an inadequate response to TNF inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1525-36.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selective immunomodulation of inflammatory pathways in keratinocytes by the janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor tofacitinib: Implications for the employment of JAK-targeting drugs in psoriasis. J Immunol Res. 2018;2018:7897263.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Tofacitinib attenuates pathologic immune pathways in patients with psoriasis: A randomized phase 2 study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;137:1079-90.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofacitinib represses the janus kinase-signal transducer and activators of transcription signalling pathway in keratinocytes. Acta Derm Venereol. 2018;98:772-75.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAK inhibition using tofacitinib for inflammatory bowel disease treatment: A hub for multiple inflammatory cytokines. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2016;310:G155-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]

- Targeting JAK/STAT signaling to prevent rejection after kidney transplantation: A reappraisal. Transplantation. 2016;100:1833-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modified- versus immediate-release tofacitinib in Japanese rheumatoid arthritis patients: A randomized, phase III, non-inferiority study. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2019;58:70-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central] [Google Scholar]