Translate this page into:

Topical coal tar alone and in combination with oral methotrexate in management of psoriasis : a retrospective analysis

Correspondence Address:

PVS Prasad

Divisions of Dermatology and Community Medicine, RMMCH, Annamalainagar - 608002

India

| How to cite this article: Prasad P, John F. Topical coal tar alone and in combination with oral methotrexate in management of psoriasis : a retrospective analysis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1997;63:26-28 |

Abstract

Thirty five patients admitted with psoriasis were analysed. 16 patients received 20% crude coal tar and 19 patients received 20% crude coal tar along with methotrexate in a weekly oral schedule (15mg/wk). After 4 weeks of therapy there was total clearence in 52.6% of the patients with combination therapy, whereas only 12.5% of the patients with conventional therapy achieved this.

Introduction

Psoriasis was first described by Robert Willan in 1809 though the term was coined by Gallen.[1] Hippocrates produced meticulous description of many skin disorders including psoriasis but only in 1841 Hebra definitly differentiated between psoriasis and leprosy. An extraordinary range of substances including arsenic, mercury and potassium iodide have been used in the past in an attempt to influence the course of psoriasis.[2] Various topical agents like bland applications, crude coal tar, dithranol, corticosteroids, PUVASOL and calcipotriol have been used with variying success rates. Similarly various systemic agents ranging from PUVA, retinoids, cyclosporine A, methotrexate, and other antimitotic drugs have been used on different occasions.[3] In 1994 at Utah the rationale, safety and side effects of combination and rotational therapy have been discussed in detail.[4] Although single agents limit side effect the drugs used and decrease the costs, combination therapy is more useful than single therapy. Patients who fail to respond to single agents, or in whom the toxicity of the individual agents need to be limited are the ideal candidates for the combination therapy, where a lower dosage of each agent is used. In combination therapy one agent is discontinued after the disease has cleared and the safer of the two is used as maintenance treatment. Some combinations already tried have no added efficacy (e.g. UVB and topical steroids) or have increased toxicity (e.g. PUVA with cyclosporine).[4] Rotational therapy with PUVA, methotrexate, UVB with tar, etretinate, cyclosporine, hydroxyurea, etc., have been tried with a success rate of 50 to 90%.

In present study topical coal tar is combined with oral weekly methotrexate and compared with another group who received coal tar alone and the results are analysed. It is unique as no trials were conducted so far with this combination.

Materials and Methods

All the patients admitted at dermatology ward of Rajah Muthiah Medical College & Hospital during January 1993 to June 1996 were retrospectively analysed. The diagnosis was based on clinical grounds. The inclusion criteria were patients with chronic plaque psoriasis and patients admitted for the first time. The exclusion criteria were pregnant women, patients with less than 30% of body involvement and patients who developed toxicity due to treatment. Patients were divided into 2 groups. Group I included all patients who received 20% crude coal tar IP topically followed by sun exposure and in group II, patients who received a combination therapy with coaltar or oral weekly methotrexate were included. Methotrexate was given at 15mg oral weekly in divided doses. Routine investigations including CBC, platelet count, liver and renal function tests were done for all patients. Chest X-ray was done wherever mandatory. Patients were routinely examined during therapy and the progress in terms of plaque size, erythema and scaling was noted. All the patients were discharged once they attained complete remission. The patients were followed up as outpatients and those who were lost to follow up were contacted through a questionnaire.

Results

Fifty nine patients were admitted with psoriasis during the study period. 24 patients were excluded from the study using the exclusion criteria leaving only 35 patients for final analysis. There were 30 males and 5 females in the study group. Among the 35 patients 16 were treated only with coal tar whereas 19 patients received methotrexate in addition to coal tar. The mean age in the coal tar group (group I) was 42.26 ± 11.4 years and of the group II was 43.63 ± 17.7 years. The average duration of illness was 22.4 months in group I with the S.D. of 29.5 months and in group II was 16.6 months with the S.D. of 31.7 month. There is no statistical difference between the two. The duration of hospitalisation was calculated as 28 days in group I with the SD of 16 days and 22 days in group II with the SD of 17 days. There is also no statistical difference between the two.

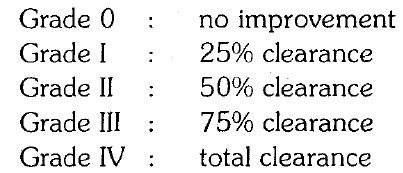

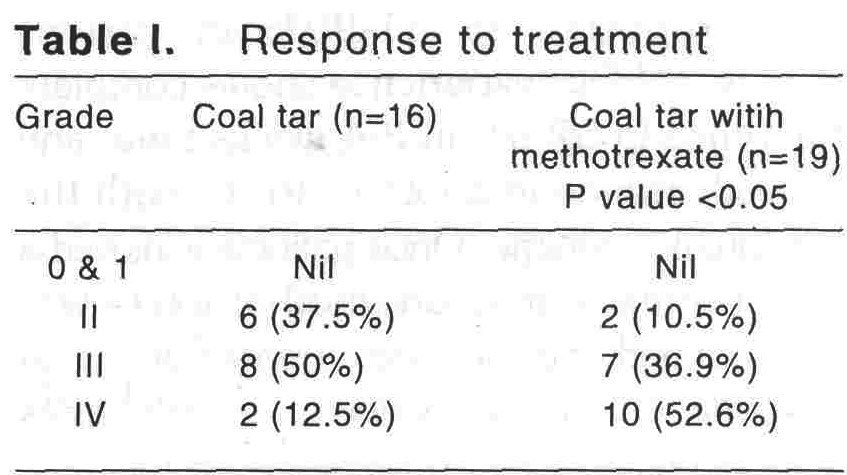

Responsi to therapy at 3-4 weeks was graded as follows:

[Table - 1] clearly indicates that there is a significant difference in response to therapy. 52.6% (10 patients) had shown complete remission with the combination therapy, whereass, only 12.5% had this response with coal tar. Similarly 10.5% (2 patients) only showed around 50% improvement in group II, whereas 37.5% (6 patients) had shown only 50% improvement in group I.

Discussion

As Wilson points out rightly `psoriasis is at all times and under all forms a very troublesome and often intractable disease, but it is rarely dangerous to life′.[5] Coal tar is produced by the primary condensation during corbonization of coal.[6] In 1931 Goeckerman popularised his therapy of coal tar in psoriasis.[7] Pery et al achieved a clearance rate of 80% in 3-6 weeks with 2-5% crude coal tar.[8] In our study with 20% crude coal tar solution 50% of patients had more than 75% clearance by the end of 3 - 4 weeks and only 12.5% had complete clearence. Despite various studies with a vast difference in cure rate it is difficult to quantify the success rates with tar regimens as standardization of coal tar is not possible. Gubner first demonstrated the beneficial effect of aminopterin in psoriasis.[9] Aminopterin was later replaced by methotrexate which is a more stable analogue. Methotrexate inhibits DNA synthesis by competitive inhibition of dihydrofolate reductase, exerting a strong anti mitotic action on the epidermis.[10] According to Walsdorfer methotrexate inhibits the polymorphonuclear luekocyte chemotaxis in psoriasis.[11] Though there are various regimens to advocate methotrexate, oral weekly schedules are very safe in psoriasis and widely accepted. The oral weekly schedule ranges from a minimum of 7.5mg in 3 divided doses to a maximum of 22.5mg. With this drug a clearance rate of >75% has been reported in 31-90% in various studies.[12],[13] Our experience shows complete clearence in 52.6% in 3-4 weeks time, and 75% clearence in another 36.9% with the combination regime. Once patients achieved a near normal remission, methotrexate was discontinued and they were treated with coal tar alone for a further period of 1-2 months as outpatients.

Relapse rate could not be calculated for both the groups as the patients′ compliance was very poor due to low socioeconomic standards.

Side effects were encountered only in 4 patients. One patient had gastritis with methotrexate and the other complained of severe generalised burning sensation over the skin which lasted for 2-3 days. With coal tar 2 patients developed folliculitis and were withdrawn from the study. In contrast to usual ′liver scare′ with methotrexate none of our patients had developed hepatotoxicity. This could be attributed to the prior selection of patients and short duration of therapy.

In conclusion, with proper selection of patients, chronic plaque psoriasis shows a high clearance rate if coal tar application is combined with oral weekly methotrexate, than with the conventional coal tar therapy alone.

| 1. |

Bechet PE. Psoriasis, a brief historical review. Arch Dermatol 1936;33:327-34.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Kerkhof Van de PCM. Introduction: therapy. In: Textbook of psoriasis. Edinburgh : Churchill Livingstone, 1986:167.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Camp RDR. Psoriasis. In: Champion RH, Burton JL, Ebling FJG, eds. Textbook of dermatology. London: Blackwell Scientific Publication, 1992:1391-1459.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Alanmenter M, Jo-Ann See, William JCA, et al. Proceedings of the psoriasis combination and rotation therapy conference. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;34:315-21.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Wilson E. In: Disease of the skin. London: Churchill, 1842:229.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Gruber M, Klein R, Foxx M. Chemical standardization and quality assurance of whole crude coal tar USP utilizing GLC procedures. J Pharmaceut Sci 1970;59:830-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Goeckerman WH. Treatment of psoriasis. Arch Dermatol Syphilol 1931;24:446-50.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Perry HO, Soderstrom CW, Schulze RW, The Goeckerman treatment of psoriasis. Arch Dermatol 1968;98:178-82.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Grbner R. Effect of 'aminopterin' on epithelial tissues., Arch Dermatol 1983;119:513-24.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Taylor JR, Halprin KM, Levine V. et al. Effects of methotrexate in vitro on epidermal cell proliferation Br J Dermatol 1983;108:45-61.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Walsdorfer U, Christophers E, Schorder J-M. Methotrexate inhibits polymorphonuclear leucocyte chemotaxis in psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 1983;108:451-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Kerkhof Van de PCM. Methotrexate. In:Mier PD, Kerkhof Van de PCM, eds. Textbook of psoriasis. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1987:233-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Kerkhof. Van de PCM, Volden G, Gollinick H. Comparisons and combinations In: Mier PD, Kerkhof Van de PCM, eds. Textbook of psoriasis. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1987;268-75.

[Google Scholar]

|