Translate this page into:

Use of fumaric acid esters in psoriasis

Correspondence Address:

Almut Boer

Dermatologikum, Stephansplatz 5, 20354, Hamburg

Germany

| How to cite this article: Roll A, Reich K, Boer A. Use of fumaric acid esters in psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2007;73:133-137 |

Abstract

Fumaric acid esters (FAE) are chemical compounds derived from the unsaturated dicarbonic acid fumaric acid. The usage of FAEs in treatment of psoriasis was introduced in the late 1950's. In the 1980s more standardized oral preparations of FAEs were developed containing dimethylfumarate(DMF) and salts of monoethylfumarate(MEF) as main compounds. In 1994, Fumaderm� an enteric-coated tablet containing DMF and calcium, magnesium, and zinc salts of MEF was approved for the treatment of psoriasis in Germany and since then has become the most commonly used systemic therapy in this country. Fumaric acids have been proven to be an effective therapy in patients with psoriasis even though the mechanisms of action are not completely understood. About 50-70% of the patients achieve PASI 75 improvement within four months of treatment and without any long-term toxicity, immunosuppressive effects, or increased risk of infection or malignancy. Tolerance is limited by gastrointestinal side effects and flushing of the skin. This article reviews pharmacokinetics, uses, contraindications, dosages, and side effects of treatment with FAEs.

Fumaric acid esters (FAE) are chemical compounds derived from the unsaturated dicarbonic acid, fumaric acid. Fumaric acid is a white crystalline powder with a characteristic acidic taste. It is used as a food additive and is commonly found as flavoring agent in cakes and sweets. Fumaric acid is poorly absorbed and believed to pass through the body without causing any effects. However, esters of fumaric acid (FAEs), such as monoethylfumarate(MEF), monomethylfumarate (MMF), diethylfumarate (DEF) and dimethylfumarate(DMF) are potent chemicals and have been used in the treatment of psoriasis in European countries for over 30 years.

The use of FAEs in the treatment of psoriasis was first introduced in the late 1950s by a German chemist named Schweckendiek. A ′fumaric acid′ protocol for psoriasis was introduced that proposed the use of FAEs as oral and topical treatment (ointment and bathing solution). [1] In the 1980s, more standardized oral preparations of FAEs were developed containing dimethylfumarate(DMF) and salts of monoethylfumarate (MEF) as the main ingredients. These were used in thousands of patients in different European countries including Germany, Switzerland and The Netherlands. In 1994, Fumaderm ® , an enteric-coated tablet containing DMF and calcium, magnesium and zinc salts of MEF was approved for the treatment of psoriasis in Germany and since then has become the most commonly used systemic therapy in this country. [2] DMF is rapidly metabolized to monomethyl fumarate (MMF) which, together with DMF, is regarded as the main bioactive metabolite.

Although data from controlled clinical trials is limited, available studies suggest that up to 50% of patients treated with Fumaderm ® achieve at least 75% reduction of their baseline ′psoriasis area and severity index′ (PASI) after 12-16 weeks of treatment. [3],[4] The most common side effects during induction therapy are flushing and gastrointestinal side effects such as nausea, vomiting and diarrhea which may lead to treatment discontinuation in as many as 30% of the patients. One major advantage of Fumaderm ® is its excellent efficacy and tolerability during long-term treatment. In long-term studies, 50-70% of the patients experience improvements of ≥ 70% after 1 year of therapy. [5],[6],[7],[8] In Germany, large numbers of responding patients have been treated for several years and patients with successful continuous therapy for 10 or more years are not uncommon. Leukopenia (particularly lymphopenia) is a concern during long-term FAE treatment. However in contrast to methotrexate (MTX), lymphopenia is usually not significant, not associated with signs of immunosuppression and is reversible within weeks after cessation of treatment. Impairment of renal function has been observed in some patients in the days of non-standardized FAE therapy and is a very rare event now with Fumaderm ® . Nonetheless, control of creatinine levels is mandatory during treatment with FAEs and therapy should be stopped if increased creatinine levels are noticed. Fumaderm ® is effective in patients who can not be successfully treated with either UV phototherapy with or without retinoids or MTX or cyclosporine. [3] There is also evidence for the synergistic effects of the combination of Fumaderm ® with topical therapies, especially calcipotriol. [9]

Pharmacokinetics

Little is known about the pharmacokinetics of FAEs. Recent in vitro data suggests that hydrolysis of DMF to the bioactive metabolite MMF occurs rapidly at pH 8 (simulating the alkaline pH found in the small intestines) but not at pH 1, which is the pH found in the stomach. [10] This indicates that hydrolysis of DMF occurs mainly in the small intestine. Most likely, MMF and MEF are then absorbed into the blood circulation where they interact with blood cells. MMF and MEF may also influence inflammatory cells in psoriatic lesions. In humans, serum concentrations of MMF after oral intake reach peak levels within 5-6 hours. MMF is further metabolized to fumaric acid and finally to H 2 O and CO 2 , the latter being eliminated via respiration where it is detectable as early as 80 minutes after oral intake. [11]

Mechanism of action

The major current hypothesis of the pharmacodynamic effect of FAEs is based on the concept that DMF and MMF influence pro-inflammatory signal transduction pathways through modulation of the intracellular redox system. [6],[7] There is evidence that changes in this system contribute to a decreased translocation of nuclear factor kappa B leading to an inhibition of the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines including TNF-a, interleukin (IL)-8 and IL-1b. Through this and other activities, FAEs modulate a variety of events involved in the exaggerated immune response in psoriasis. It has been concluded mostly from in vitro experiments that FAEs mediate the following anti-inflammatory, immune-modulatory and anti-proliferative effects:

- Inhibition of the cytokine-induced expression of adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-selectin on dermal fibroblasts [12],[13] and endothelial cells. [14]

- Suppression of not only the production of T helper type-1 and pro-inflammatory mediators such as TNF-a and IFN-g but enhancement of the formation of cytokines with anti-inflammatory properties such as IL-10 and IL-1RA. [15],[16]

- Decrease of the maturation and T helper type-1-inducing capacity of dendritic and other antigen presenting cells and promotion of apoptosis in these cells; the stimulation of T helper type-2 cytokine production seems to be less affected. [17],[18],[19],[20]

- Induction of apoptosis not only in antigen presenting cells but in various other immune cells including activated T cells which is accompanied by a strong induction of the anti-inflammatory stress protein heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1). [21],[22]

On the other hand, FAEs have no effects on the production of superoxide anions, which are components of the innate defense against microorganisms. [23]

USES

Plaque-type psoriasis

There is substantial evidence from at least eight clinical studies conducted between 1987 and 2004 mostly in patients with severe psoriasis, that monotherapy with FAEs is an effective treatment of this condition. [4]

Pustular psoriasis

There are a few reports of successful treatment of pustular psoriasis with FAEs. [24],[25]

Psoriasis capitis

Due to the lack of controlled clinical trials, efficacy of FAEs in this manifestation of psoriasis has not been documented. In clinical experience, FAEs can be helpful in controlling severe cases of psoriasis capitis presenting incomplete response to topical therapy alone.

Psoriatic arthritis (PsA)

There is evidence that FAEs have some efficacy in the treatment of psoriatic arthritis. [26] In clinical practice, FAEs are useful in patients with plaque-type psoriasis and mild PsA. In more aggressive cases of PsA or if PsA is the predominant manifestation of psoriasis, other therapies such as MTX or TNF antagonists are more appropriate.

Nail psoriasis

This often very-difficult-to-treat manifestation of psoriasis shows at least some improvement during long-term treatment with FAEs in many patients. [27] However, controlled trials are not available.

Uses other than psoriasis

Disseminated granuloma annulare

There are case reports describing successful treatment of patients with disseminated granuloma annulare with FAEs. [28],[29],[30],[31] FAEs may represent a therapeutic option in more severe cases unresponsive to treatment with PUVA and potent topical corticosteroids.

Sarcoidosis

Some authors claim to have observed a positive effect of FAEs in cutaneous and systemic sarcoidosis. [32],[33]

Necrobiosis lipoidica

There is data for the treatment of eighteen patients with histopathologically proven necrobiosis lipoidica with FAEs according to the standard schedule for psoriasis (see below). [34] After a mean treatment period of 7.7 months, a significant decrease in the mean clinical score was observed. The improvement remained stable over six months of follow-up.

CONTRAINDICATIONS

FAEs should not be used in patients with significant gastrointestinal diseases such as chronic gastritis or active or recent gastric or duodenal ulcers. Patients suffering from severe liver or kidney diseases, patients under the age of 18 and women during pregnancy or lactation should also not be treated with FAEs. [4],[35],[36]

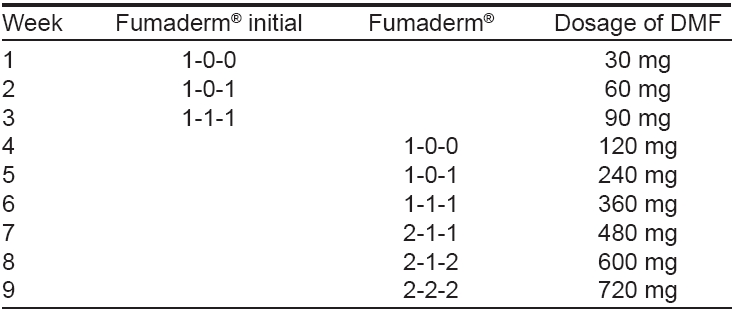

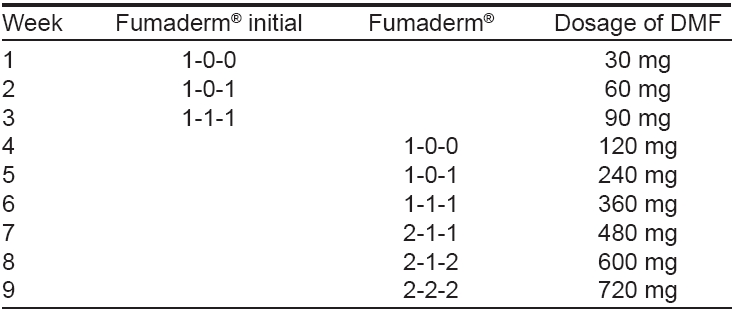

DOSAGES

The established treatment regimen of FAEs in psoriasis proposes a gradual increase in dosage according to the schedule depicted in [Table - 1]. This schedule has been shown to improve gastrointestinal tolerance. [4] In each patient, the final daily dosage needs to be adjusted according to the individual response and the onset of adverse effects. One tablet of Fumaderm initial ® appears to be a reasonable starting dose for a dose-escalation protocol. Dose escalation is continued until a satisfactory clinical response is reached and then the dosage is steadily reduced to an individual maintenance dose. The final dosage may range up to 1-2 g/d (6 tablets of Fumaderm ® ). Most patients treated with fumaric acids require two to four tablets of Fumaderm ® . Dosage is neither related to body weight nor to the activity of the disease. Treatment may be discontinued abruptly as relapse or rebound phenomena do not occur. [4]

RECOMMENDATIONS

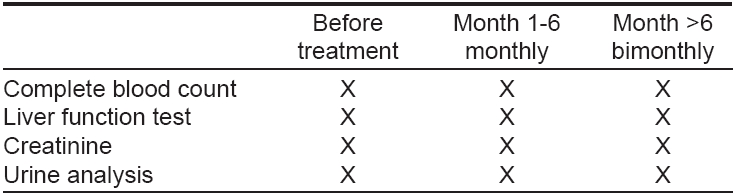

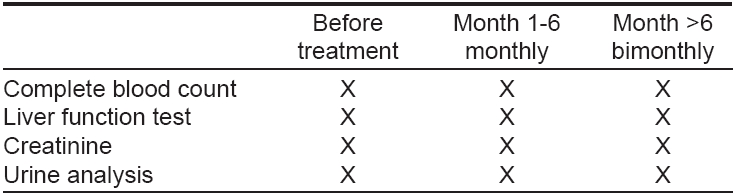

Recommendations for follow-up investigations are given in [Table - 2]. Treatment should be discontinued immediately when lymphocytes decrease below 500/µl or when serum creatinine levels increase above the normal range. [4]

CONCOMITANT THERAPY

Currently, a combination of fumaric acids with systemic medication, i.e., cyclosporine or methotrexate is not recommended because of lack of experience. However, the additional use of calcipotriol administered topically has been shown to significantly increase the efficacy of FAE treatment with faster resolution of psoriatic lesions than with FAE monotherapy. [9]

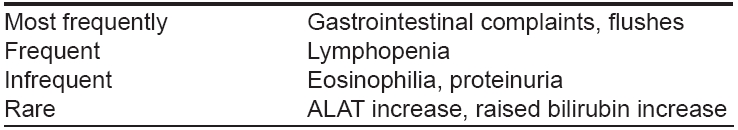

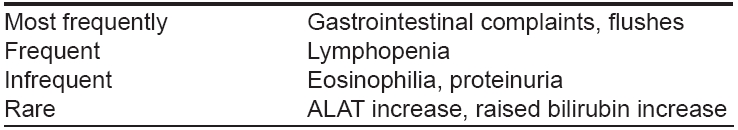

SIDE EFFECTS

Side effects of treatment with FAEs are summarized in [Table - 3]. Adverse events during treatment with fumaric acids are common and are reported in up to two thirds of all patients. [5],[27] The most common side effects are gastrointestinal symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, nausea and malaise. These signs and symptoms occur primarily within the first few weeks after initiation of treatment and within 90 minutes to six hours after oral intake of the drug. They last for several minutes up to half an hour and can be alleviated by intake of tablets with milk. Flushing of the skin is another common complaint, ranging from rapid sensation of heat to long-lasting facial redness. Improvement of the latter side effect has been seen on treatment with acetylsalicylic acid but this has not yet been confirmed scientifically. The adverse effects just mentioned are dose-dependent and they decrease in frequency during the course of the treatment.

Less commonly observed side effects are lymphocytopenia, leukocytopenia and elevated eosinophil counts. A decrease of lymphocytes below 500/mm 3 should lead to dosage reduction or withdrawal of treatment. The eosinophilia is transient and usually observed between the fourth and tenth week of treatment.

Rarely, moderate elevations of liver enzymes and bilirubin have been observed. Proteinuria has been noted too, but it proved to be transient. [4],[37],[38] An increased risk for infections has not been documented.

Teratogenicity/Pregnancy/Lactation

Toxicologic investigations have given no evidence that fumaric acids are teratogenic or mutagenic. Nevertheless, fumaric acids should be avoided in pregnancy or lactation because data for use in these conditions is limited. [4],[37],[38]

DRUG INTERACTIONS

FAEs have no known metabolic interactions with other drugs. Concurrent use of fumaric acids with other drugs having side effects on kidney function should be avoided because of increased toxicity (e.g., methotrexate, cyclosporine, psoralen, immunosuppressive drugs and cytostatics).

Fumaric acids have been proven to be an effective therapy in patients with psoriasis even though the mechanisms of action are not completely understood. According to the German S3-guidelines of psoriasis, evaluation of 13 studies has shown a proportion of 50-70% of patients who achieved PASI 75 improvement within four months of treatment and without any long-term toxicity, immunosuppressive effects or increased risk of infection or malignancy. [4] Tolerance is limited by gastrointestinal side effects and flushing of the skin in about two thirds of the patients. These side effects are dose-dependent and decrease in frequency in the course of treatment. Monitoring of full blood cell count, liver and kidney function as well as urine analysis is necessary. Improvement of lesions of psoriasis on fumaric acids may be accelerated by combination with topical agents such as calcipotriol.

| 1. |

Schweckendiek W. Treatment of psoriasis vulgaris. Med Monatsschr 1959;13:103-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Sch φpf E, Augustin M. Therapie der Psoriasis mit Fumarsδureestern. Dt �rztebl 1996;93:A-3182-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Ormerod AD, Mrowietz U. Fumaric acid esters, their place in the treatment of psoriasis. Br J Dermatol 2004;150:630-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Nast A, Kopp IB, Augustin M, Banditt KB, Boehncke WH, Follmann M, et al . S3-Leitlinie zur Therapie der Psoriasis vulgaris. J German Soc Dermatol 2006;4:51-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Altmeyer P, Hartwig R, Matthes U. Efficacy and safety profile of fumaric acid esters in oral long-term therapy with severe treatment refractory psoriasis vulgaris. A study of 83 patients. Hautarzt 1996;47:190-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Altmeyer PJ, Matthes U, Pawlak F, Hoffmann K, Frosch PJ, Ruppert P, et al . Antipsoriatic effect of fumaric acid derivates: Results of a multicenter double-blind study in 100 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol 1994;30:977-81.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Mrowietz U, Christophers E, Altmeyer P. Treatment of psoriasis with fumaric acid esters: Results of a prospective multicentre study. German Multicentre Study. Br J Dermatol 1997;138:456-60.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Mrowietz U, Christophers E, Altmeyer P. Treatment of severe psoriasis with fumaric acid esters: Scientific background and guidelines for therapeutic use. The German Fumaric Acid Ester Consensus Conference. Br J Dermatol 1999;141:424-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Gollnick H, Altmeyer P, Kaufmann R, Ring J, Christophers E, Pavel S, et al . Topical calcipotriol plus oral fumaric acid is more effective and faster acting than oral fumaric acid monotherapy in the treatment of severe chronic plaque psoriasis vulgaris. Dermatology 2002;205:46-53.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Litjens NH, van Strijen E, van Gulpen C, Mattie H, van Dissel JT, et al . In vitro pharmacokinetics of anti-psoriatic fumaric acid esters. BMC Pharmacol 2004;4:22.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Fachinformation zu Fumaderm� initial/Fumaderm� . FumedicaArznei-mittel GmbH, Heme: 1996.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Mrowietz U, Asadullah K. Dimethylfumarate for psoriasis: More than a dietary curiosity. Trends Mol Med 2005;11:43-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Vandermeeren M, Janssens S, Wouters H, Borghmans I, Borgers M, Beyaert R, et al . Dimethylfumarate is an inhibitor of cytokine-induced nuclear translocation of NF-kappa B1, but not RelA in normal human dermal fibroblast cells. J Invest Dermatol 2001;116:124-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Vandermeeren M, Janssens S, Borgers M, Geysen J. Dimethylfumarate is an inhibitor of cytokine-induced E-selectin, VCAM-1 and ICAM-1 expression in human endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1997;234:19-23.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Asadullah K, Schmid H, Friedrich M, Randow F, Volk HD, Sterry W, et al . Influence of monomethyl fumarate on monocytic cytokine formation--explanation for adverse and therapeutic effects in psoriasis? Arch Dermatol Res 1997;289:623-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Litjens NH, Nibbering PH, Barrois AJ, Zomerdijk TP, Van Den Oudenrijn AC, Noz KC, et al . Beneficial effects of fumarate therapy in psoriasis vulgaris patients coincide with downregulation of type 1 cytokines. Br J Dermatol 2003;148:444-51.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Litjens NH, Rademaker M, Ravensbergen B, Thio HB, van Dissel JT, Nibbering PH. Effects of monomethyl fumarate on dendritic cell differentiation. Br J Dermatol 2006;154:211-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Litjens NH, Rademaker M, Ravensbergen B, Rea D, van der Plas MJ, Thio B, et al . Monomethyl fumarate affects polarization of monocyte-derived dendritic cells resulting in down-regulated Th1 lymphocyte responses. Eur J Immunol 2004;34:565-75.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

de Jong R, Bezemer AC, Zomerdijk TP, van de Pouw-Kraan T, Ottenhoff TH, Nibbering PH. Selective stimulation of T helper 2 cytokine responses by the anti-psoriasis agent monomethyl fumarate. Eur J Immunol 1996;26:2067-74.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Zhu K, Mrowietz U. Inhibition of dendritic cell differentiation by fumaric acid esters. J Invest Dermatol 2001;116:203-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Lehmann JC, Listopad JJ, Rentzsch CU, Igney FH, von Bonin A, Hennekes HH, et al . Dimethylfumarate Induces Immunosuppression via Glutathione Depletion and Subsequent Induction of Heme Oxygenase 1. J Invest Dermatol 2007.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Treumer F, Zhu K, Glaser R, Mrowietz U. Dimethylfumarate is a potent inducer of apoptosis in human T cells. J Invest Dermatol 2003;121:1283-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Zhu K, Mrowietz U. Enhancement of antibacterial superoxide-anion generation in human monocytes by fumaric acid esters. Arch Dermatol Res 2005;297:170-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Stander H, Stadelmann A, Luger T, Traupe H. Efficacy of fumaric acid ester monotherapy in psoriasis pustulosa palmoplantaris. Br J Dermatol 2003;149:220-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Pawlak FM, Matthes U, Bacharach-Buhles M, Altmeyer P. Behandlung einer therapieresistenten Psoriasis pustulosa generalisata mit Fumarsδureestern. Akt. Dermatol 1993;19:6-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Peeters AJ, Dijkmans JK, van der Schroeff JG. Fumaric acid therapy for Psoriatic Arthritis. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Rheumatol 1992;31:502-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Mrowietz U, Christophers E, Altmeyer P. Treatment of psoriasis with fumaric acid esters: Results of a prospective multicentre study. German Multicentre Study. Br J Dermatol 1998;138: 456-60.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Breuer K, Gutzmer R, Volker B, Kapp A, Werfel T. Therapy of noninfectious granulomatous skin diseases with fumaric acid esters. Br J Dermatol 2005;152:1290-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 29. |

Eberlein-Konig B, Mempel M, Stahlecker J, Forer I, Ring J, Abeck D. Disseminated granuloma annulare--treatment with fumaric acid esters. Dermatology 2005;210:223-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 30. |

Kreuter A, Gambichler T, Altmeyer P, Brockmeyer NH. Treatment of disseminated granuloma annulare with fumaric acid esters. BMC Dermatol 2002;2:5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 31. |

Schulze-Dirks A, Petzoldt D. Granuloma annulare disseminatum: Successful therapy with fumaric acid ester. Hautarzt 2001;52: 228-30.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 32. |

Gutzmer R, Kapp A, Werfel T. Successful treatment of skin and lung sarcoidosis with fumaric acid ester. Hautarzt 2004;55: 553-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 33. |

Nowack U, Gambichler T, Hanefeld C, Kastner U, Altmeyer P. Successful treatment of recalcitrant cutaneous sarcoidosis with fumaric acid esters. BMC Dermatol 2002;2:15.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 34. |

Kreuter A, Knierim C, Stucker M, Pawlak F, Rotterdam S, Altmeyer P, et al . Fumaric acid esters in necrobiosis lipoidica: Results of a prospective non-controlled study. Br J Dermatol 2005;153:802-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 35. |

Dalhoff K, Faerber P, Arnholdt H, Sack K, Strubelt O. Acute kidney failure during psoriasis therapy with fumaric acid derivatives. Dtsch Med Wochenschr 1990;115:1014-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 36. |

Roodnat JI, Christiaans MH, Nugteren-Huying WM, van der Schroeff JG, Chang PC. Acute kidney insufficiency in patients treated with fumaric acid esters for psoriasis. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1989;133:2623-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 37. |

Bayard W, Hunziker T, Krebs A, Speiser P, Joshi R. Peroral long-term treatment of psoriasis using fumaric acid derivatives. Hautarzt 1987;38:279-85.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 38. |

Altmeyer P, Hartwig R, Matthes U. Efficacy and safety profile of fumaric acid esters in oral long-term therapy with severe treatment refractory psoriasis vulgaris. A study of 83 patients. Hautarzt 1996;47:190-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

7,539

PDF downloads

2,983