Translate this page into:

Adult cutaneous myofibroma

Correspondence Address:

V Kharkar

Department of Dermatology, KEM Hospital and GS Medical College, Parel, Mumbai - 12

India

| How to cite this article: Patel V, Kharkar V, Khopkar U. Adult cutaneous myofibroma. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:56-58 |

Abstract

A 63-year-old male presented with an asymptomatic, slow-growing swelling on the right lower limb for the past one and half years. The histopathology revealed a lobular neoplasm with a biphasic pattern of spindle shaped cells and hemangiopericytoma like areas at the periphery of the lobule. The diagnosis of adult cutaneous myofibroma was made. This case highlights the importance of histopathology in reaching a definitive diagnosis. |

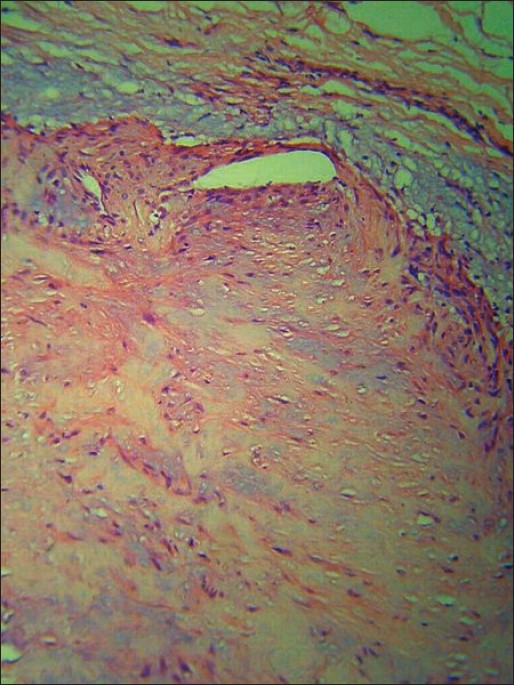

| Figure 3: Biphasic pattern of the neoplastic cells (H and E stain, X200) |

|

| Figure 3: Biphasic pattern of the neoplastic cells (H and E stain, X200) |

|

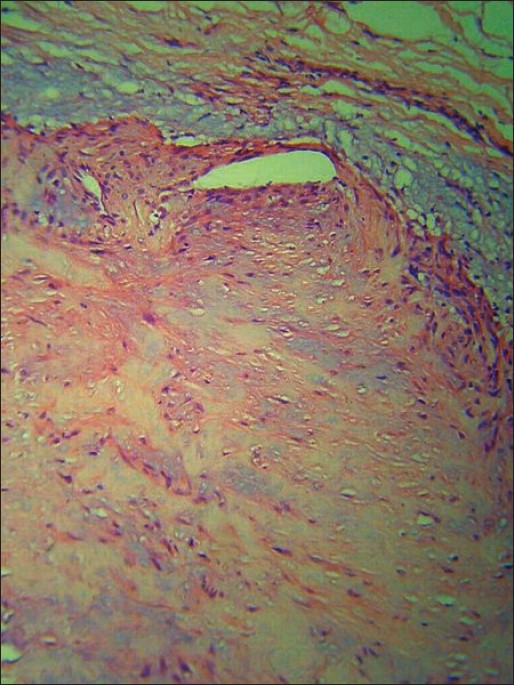

| Figure 2: Well circumscribed non-epithelial lobulated neoplasm (H and E stain, X40) |

|

| Figure 2: Well circumscribed non-epithelial lobulated neoplasm (H and E stain, X40) |

|

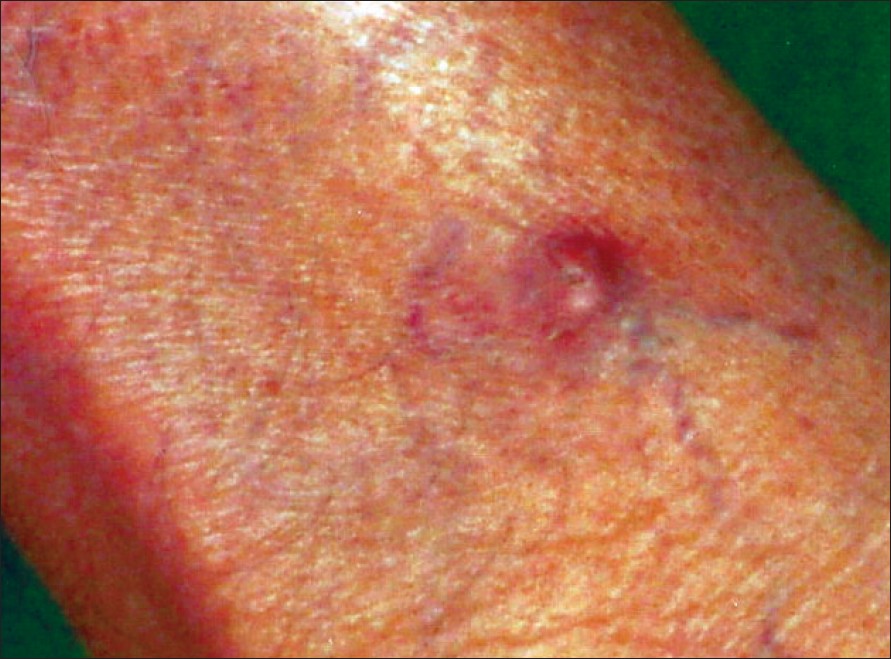

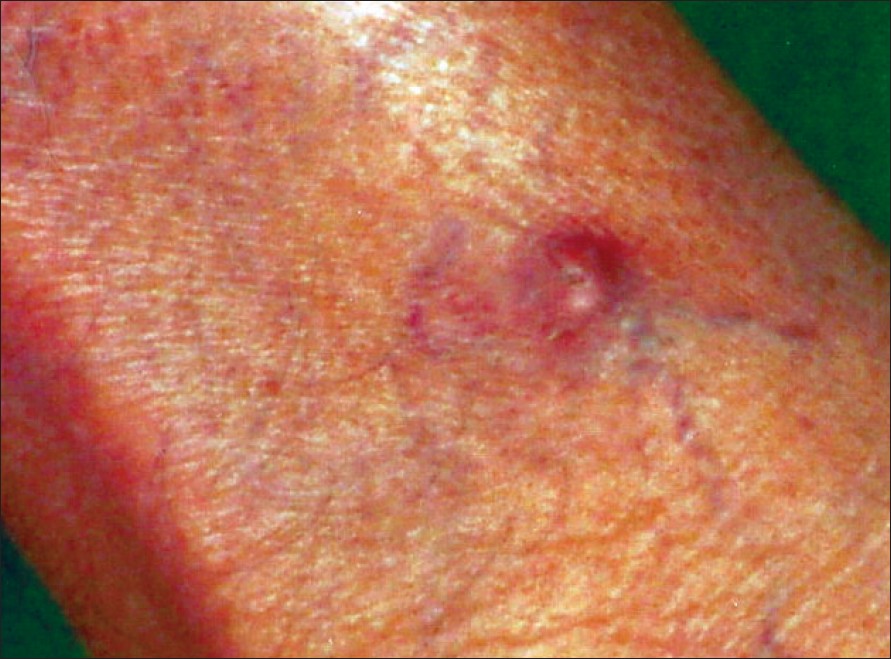

| Figure 1: Solitary pinkish nodule on the leg |

|

| Figure 1: Solitary pinkish nodule on the leg |

Introduction

Adult solitary cutaneous myofibroma is a relatively recently described entity. It is considered the adult counterpart of multiple juvenile fibromatosis. The condition is of great interest amongst dermatologists and pathologists because of characteristic histopathology, which raises queries regarding the tissue of origin: blood vessels or muscle. We herewith present a case of solitary adult myofibroma and review the literature for better understanding of this disorder.

Case Report

A 63-year-old male, normotensive and non-diabetic, presented with an asymptomatic nodule on the right lower limb of one and a half years duration. The lesion had started as a small swelling and had slowly grown to the present size. There was no history of preceding trauma or insect bite. The growth was asymptomatic without pain, bleeding or ulceration. There were no systemic complaints.

On examination, there was a pink, slightly elevated nodule of about 1 cm diameter, on the anterior aspect of the right shin [Figure - 1]. It was firm, painless and dermal in location. Buttonhole sign and Fitzpatrick′s sign were negative. There was no sensitivity to cold or heat or any symptom associated with stress.

Systemic examination was normal. On the basis of clinical findings, our diagnostic possibilities were soft-tissue tumor, dermatofibroma or leiomyoma. An excision biopsy was performed for histopathological diagnosis. The histopathological picture was characteristic showing a well-circumscribed, non-epithelial tumor mass with a lobulated appearance [Figure - 2]. The individual lobules showed typical biphasic pattern of cellular arrangement with pale, hyalinized areas with elongated nuclei of myofibroblasts predominating at the center of the lobule [Figure - 3]. Hemangiopericytoma-like areas made up of closely aggregated small, round and oval cells were present at the periphery of the lobules. Many of these cells lined the thick-walled capillaries in this area. Abundant mucin was seen at the periphery of the lobules. The rest of the dermis and epidermis were normal. Immunostaining for actin, desmin, vimentin, S-100 and Factor XIII could not be done because of technical and cost constraints. Based on clinico-pathological features, a diagnosis of solitary cutaneous myofibroma was made. The patient was asked to come for follow-up every six months and during the first follow-up, there was no evidence of recurrence.

Discussion

The rare but currently well-recognized entity, called ′juvenile fibromatosis′ was first described by Stout in 1954. [1] The condition is characterized by an asymptomatic slow-growing tumor mass, noted at birth or during the first weeks of life. Solitary lesions are at least twice as common as multiple lesions. Skin, soft-tissue and bone are commonly affected. Visceral involvement is rare and prognosis is poor in such cases. Mortality is uncommon. The diagnosis of the condition is done by histopathological examination. There is a characteristic ′biphasic′ pattern consisting of fascicles of spindle cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm resembling smooth muscle and a population of more primitive spindle cells. A hemangiopericytoma-like vascular pattern, with proliferating lesional cells around blood vessels is seen. Collagen and mucin are present but are seldom abundant. [2]

A number of case reports confirming Stout′s findings were described in subsequent years and the occurrence of tumors at various body sites was recorded. [3],[4],[5] The condition was named ′infantile myofibromatosis′. There are several case reports of asymptomatic, firm and slow-growing tumors in middle-aged and older individuals, clinically and histopathologically similar to juvenile myofibroma. [6],[7] These adult counterparts of ′infantile-type myofibromatosis′ are named ′adult myofibromas′. [8]

Myofibromatosis is an admixture of myofibroblasts and fibroblasts in a fibrous stroma. Some authors prefer to use the term ′myofibroma′ for single lesions, especially those with adult onset and myofibromatosis for multifocal involvement. This is considered to be a developmental anomaly with rare occurrence in adults. Various types have been described: the solitary infantile, congenital and multiple without any visceral involvement, congenital and generalized with cutaneous and visceral lesions and the solitary cutaneous myofibroma occurring in adults.

Adult cutaneous myofibroma characteristically occurs on the extremities. It is commonly a solitary, painless, slow- growing, cutaneous or subcutaneous nodule with occasional bluish hue. In early stages it is mostly ignored but larger lesions result in cosmetic concern. Systemic and multicentric lesions are rare in adults. The tumor has been reported to occur at atypical sites like the mandible and pinna. [9],[10],[11] The tumor is common among middle-aged individuals, although age of patients may range from 17 to 78 years. [11] There is no sex predilection. Differential diagnoses include neurothekeomas, plexiform fibrous histiocytomas, nodular fasciitis, cutaneous inflammatory pseudotumors, dermatomyofibromas, leiomyomas and other forms of fibromatosis affecting the skin and superficial soft tissues. [12]

Histopathological examination is necessary for diagnosis and the ′biphasic′ appearance described above is the hallmark of the condition. Classically, each lesion has a biphasic pattern with spindle cells forming fascicular or whorled areas and rounded, more primitive cells arranged around the small vessels, forming hemangiopericytoma-like areas. The characteristic zones of infantile myofibromatosis are often less marked in adult lesions and there is a haphazard arrangement of the fascicular and pericytic areas in some cases. [13] The background stroma in the fibromyxoid areas is sometimes hyalinized. The architecture is often lobulated. Mucin is also seen in some cases and vascular invasion is very rare. Recently, four histopathologic patterns have been described: leiomyoma or fascicular type, cellular (spindle cell) or nodular type, hemangiopericytoma or glomus (vascular) type and biphasic or multinodular type, which has a central hemangiopericytoma-like vascular spaces and a periphery resembling leiomyoma. [13] A correlation between the histopathological pattern and the lesional age has been observed; vascular type of cutaneous adult myofibroma in early lesions, nodular and multinodular lesions in fully developed lesions and leiomyoma-like or fascicular type in late lesions. [13]

Immunohistochemically, the spindle cells are desmin negative, but express immunoreactivity for vimentin, pan-smooth muscle actin and alpha-smooth muscle actin (HHF-35 and IA4). [13],[14] The rounded cells are negative for both actin and desmin. Ultrastructurally, cells show characteristics of undifferentiated mesenchymal cells with features of fibroblasts, myofibroblasts and pericytes. [13] Primitive vascular formations are seen in the form of irregular clefts between adjoining cells.

Based on the clinical, histopathological and immunohistochemical features, it is generally accepted that adult myofibroma is a tumor of vascular origin. [7],[13] It has also been proposed that adult myofibroma, glomangiopericytoma and myopericytoma represent a histopathological continuum of tumors which should be categorized more appropriately as ′perivascular myomas′. [11] Unlike the infantile tumors, the adult variant does not show a tendency to spontaneous regression. They have completely benign biological behavior and excision of the tumor is curative. Local recurrences have been reported in certain series. [11] Hence, periodic follow-ups should be advised. These tumors have no malignant potential and any such case is yet to be reported.

To conclude, adult cutaneous myofibroma is a benign, asymptomatic, slow-growing neoplasm of vascular origin belonging to the group of ′perivascular myomas′. These arise on the extremities in middle-aged individuals and show a characteristic ′biphasic′ histopathologic picture. There is no tendency to spontaneous regression and excision is curative.

| 1. |

Stout AP. Juvenile fibromatosis. Cancer 1954;7:953-78.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Fletcher CD, Ach P, Van Noorden S, McKee PH. Infantile myofibromatosis: A light microscopic, histochemical and immunohistochemical study suggesting true smooth muscle differentiation. Histopathology 1987;11:245-58.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Venencie PV, Bigtel P, Desgruelles C, Lortat-Jacob S, Dufier JL, Saurat JH. Infantile myofibromatosis. Br J Dermatol 1987;117:255-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Spraker MK, Stack C, Esterly NB. Congenital generalized fibromatosis: A review of the literature and report of a case associated with porencephaly, hemiatrophy, and cutis marmorata. J Am Acad Dermatol 1984;10:365-71.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Slootweg PJ, Muller H. Localized infantile myofibromatosis: Report of a case originating in the mandible. J Maxillofac Surg 1984;12:86-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Daimaru Y, Hashimoto H, Enjoji M. Myofibromatosis in adults: Adult counterpart of infantile myofibromatosis. Am J Surg Pathol 1989;13:859-65.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Smith KJ, Skelton HG, Barrett TL, Lupton GP, Graham JH. Cutaneous myofibroma. Mod Pathol 1989;2:603-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Calonje E, Fletcher CD. New entities in cutaneous soft tissue tumours. Pathologica 1993;85:1-15.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Oliver RJ, Coulthard P, Carre C, Sloan P. Solitary adult myofibroma of the mandible simulating an odontogenic cyst. Oral Oncol 2003;39:626-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Balakrishnan R, Pujary K, Shah P, Hazarika P. Solitary adult myofibroma of the pinna. J Laryngol Otol 1999;113:155-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Granter SR, Badizadegan K, Fletcher CD. Myofibromatosis in adults, glomangiopericytoma and myopericytoma: A spectrum of tumors showing perivascular myoid differentiation. Am J Surg Pathol 1998;22:513-25.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Guitart J, Ritter JH, Wick MR. Solitary cutaneous myofibromas in adults: Report of six cases and discussion of differential diagnosis. J Cutan Pathol 1996;23:437-44.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Requena L, Kutzner H, Hugel H, Rutten A, Furio V. Cutaneous adult myofibroma: A vascular neoplasm. J Cutan Pathol 1996;23:445-57.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Beham A, Badve S, Suster S, Fletcher CD. Solitary myofibroma in adults: Clinicopathological analysis of a series. Histopathology 1993;22:335-41.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

4,501

PDF downloads

2,111