Translate this page into:

Many faces of cutaneous leishmaniasis

2 Department of Dermatology, Military Hospital, Rawalpindi, Pakistan

Correspondence Address:

Arfan Ul Bari

Consultant Dermatologist, Combined Military Hospital, Muzaffarabad, AJK

Pakistan

| How to cite this article: Bari A, Rahman SB. Many faces of cutaneous leishmaniasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2008;74:23-27 |

Abstract

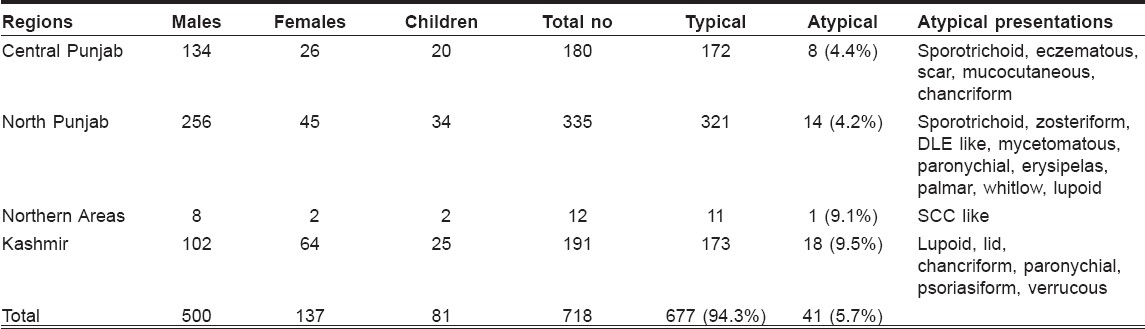

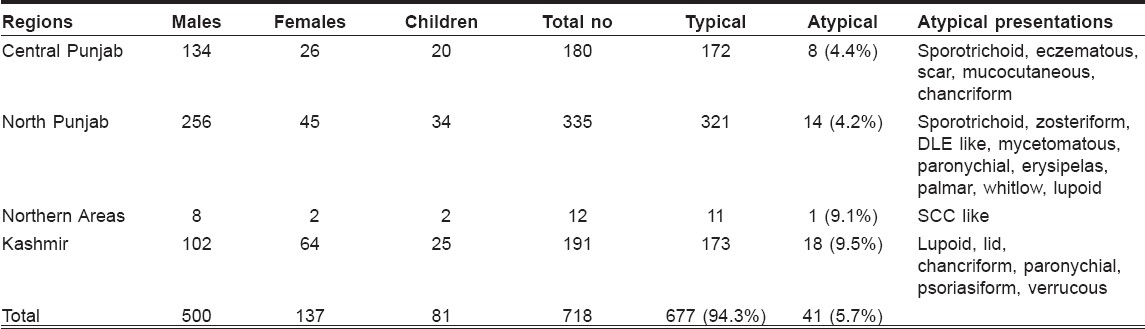

Background: Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is known for its clinical diversity and increasing numbers of new and rare variants of the disease are being reported these days. Aim: The aim of this descriptive study was to look for and report the atypical presentations of this common disease occurring in Pakistan. Methods: The study was carried out in three hospitals (MH, Rawalpindi; PAF Hospital, Sargodha; and CMH, Muzaffarabad) from 2002 to 2006. Military and civilian patients of all ages, both males and females, belonging to central and north Punjab province and Kashmir were included in the study. Clinical as well as parasitological features of cutaneous leishmaniasis were studied. The unusual lesions were photographed and categorized accordingly using simple descriptive statistics. Results: Out of 718 patients of cutaneous leishmaniasis, 41 (5.7%) had unusual presentations. The commonest among unusual morphologies was lupoid leishmaniasis 14 (34.1%), followed by sporotrichoid 5 (12.1%), paronychial 3 (7.3%), lid leishmaniasis 2 (4.9%), psoriasiform 2 (4.9%), mycetoma-like 2 (4.9%), erysipeloid 2 (4.9%), chancriform 2 (4.9%), whitlow 1 (2.4%), scar leishmaniasis 1 (2.4%), DLE-like 1 (2.4%), 'squamous cell carcinoma'-like 1 (2.4%), zosteriform 1 (2.4%), eczematous 1 (2.4%), verrucous 1 (2.4%), palmar/plantar 1 (2.4%) and mucocutaneous 1 (2.4%). Conclusion: In Pakistan, an endemic country for CL, the possibility of CL should be kept in mind while diagnosing common dermatological diseases like erysipelas, chronic eczema, herpes zoster, paronychia; and uncommon disorders like lupus vulgaris, squamous cell carcinoma, sporotrichosis, mycetoma and other deep mycoses.

|

| Figure 7: Pattern of atypical clinical presentations |

|

| Figure 7: Pattern of atypical clinical presentations |

|

| Figure 6: Verruciform and heaped-up plaque over the dorsum of hand |

|

| Figure 6: Verruciform and heaped-up plaque over the dorsum of hand |

|

| Figure 5: Hyperkeratotic, eczematoid lesion of cutaneous leishmaniasis over plantar aspect of foot |

|

| Figure 5: Hyperkeratotic, eczematoid lesion of cutaneous leishmaniasis over plantar aspect of foot |

|

| Figure 4: Hyperkeratotic plaque over upper eyelid, causing mechanical ptosis |

|

| Figure 4: Hyperkeratotic plaque over upper eyelid, causing mechanical ptosis |

|

| Figure 3: Paronychial lesion of cutaneous leishmaniasis |

|

| Figure 3: Paronychial lesion of cutaneous leishmaniasis |

|

| Figure 2: Sporotrichoid pattern over dorsum of hand and forearm |

|

| Figure 2: Sporotrichoid pattern over dorsum of hand and forearm |

|

| Figure 1: Lupoid lesion involving nose and central part of the face |

|

| Figure 1: Lupoid lesion involving nose and central part of the face |

Introduction

Cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) is a major world health problem that is growing epidemically in Pakistan and Afghanistan. [1] It is a parasitic disease caused by Leishmania and transmitted by the bite of some species of sandflies and it affects various age groups. Phlebotomus papatasi, Phlebotomus sergenti and Phlebotomus salehi are the sandfly species reported from Pakistan. [2] Depending on the infecting Leishmania species and host immunocompetence, there are cutaneous, mucocutaneous and visceral forms of the disease. CL typically presents with a skin ulcer over exposed regions of the body after a sandfly bite and generally heals spontaneously within 3-6 months. In addition to classical clinical picture, several unusual and atypical clinical features of the disease have been reported in the literature. [3],[4],[5],[6],[7],[8] Lesions may appear at unusual sites or the disease may present with atypical morphologies. We recorded all the atypical and unusual morphological variants of the disease that we encountered during the last 5 years. Our cases have actually extended the spectrum of clinical presentations of CL in the Old World.

Methods

Patients of all ages and both sexes, military personnel as well as civilian population, reporting to dermatology departments of Military Hospital, Rawalpindi (January 2002 to December 2002); Pakistan Air Force Hospital, Sargodha (January 2003 to December 2005); and Combined Military Hospital, Muzaffarabad (January 2006 to December 2006), were included in the study. They either belonged to an endemic area of the disease or had traveled to some endemic region during the last 6 months. Apparently infected patients who showed clearance of their lesions after short courses of antibiotics were excluded from the study. All patients having clinically suggestive lesions (one or more discrete nodules, plaques, non-healing ulcers on exposed sites or any atypical lesion anywhere on the body not responding to repeated courses of antibiotics and anti tuberculosis drugs) were subjected to slit skin smear examination for Leishman Donovan (LD) bodies. Negative skin smears were followed by skin biopsy for histopathological diagnosis. They all had clinical and parasitological diagnosis of cutaneous leishmaniasis, but some of them exhibited unusual clinical pattern or atypical morphology of the disease. Patients initially diagnosed differently but later proving to be leishmaniasis on slit skin smears and histopathology were also included. Number of the lesions, type of the lesions, site of involvement and gross morphology of the lesions were noted before starting treatment. Any change in morphology of the lesions and new developments during progression of the disease were also recorded. Out of all these, patients with unusual lesions (other than typical papulo-nodulo-ulcerative lesions and crusted plaques) were isolated and categorized accordingly using simple descriptive statistics. All unusual lesions were also photographed. Majority of the patients were treated indoors with once-daily intramuscular injection of meglumine antimonate for 2-3 weeks. Some with isolated lesions over non-articular and nonfacial sites were given intralesional injection of meglumine antimonate twice weekly for a total of six to eight injections in the outpatient clinic. In a few patients having chronic, large, heaped-up lesions not adequately responding to systemic treatment, cryotherapy twice weekly was used as an adjunctive treatment modality.

Results

The study included 500 (69.6%) males and 137 (19.1%) females and 81 (11.3%) children. There age ranged from 2 to 68 years (mean age 25.7 years). Majority of the patients had lesions over exposed parts of the body. The duration of the disease varied between 1 and 18 months. The sites commonly affected were upper limbs (40%), lower limbs (32%), face (21%) and trunk (6%). The clinical profile that emerged was basically of the following three types: dry type (slowly evolving nodule or plaque with late ulceration, urban type) in 529 (73.7%) patients, wet type (rapidly evolving papule, nodule or plaque with early ulceration, rural type) in 156 (21.7%) patients and miscellaneous type (lupoid and other unusual morphologies) in 33 (4.6%) patients. Almost all patients who contracted the disease in Punjab had dry type lesions and patients with wet type disease were either from Kashmir or were those who had been in some endemic regions of Baluchistan or interior Sindh in the recent past or at least had visited the same areas during the last 1 year. Out of the total 718 patients, 41 (5.7%) had unusual presentations. Most common was lupoid leishmaniasis 14 (34.1%) [Figure - 1], followed by sporotrichoid 5 (12.1%) [Figure - 2] and paronychial 3 (7.3%) [Figure - 3], erysipeloid, lid leishmaniasis [Figure - 4], psoriasiform, mycetomatous and chancriform lesions were seen in 2 (4.9%) patients each. Scar leishmaniasis, zosteriform, whitlow, palmar/plantar [Figure - 5], DLE-like, squamous cell carcinoma, eczematous and verrucous morphology [Figure - 6] were seen in 1 (2.4%) patient each. Mucocutaneous lesions were seen in 1 (2.4%) child. Chronic cutaneous disease (recidivans cutaneous leishmaniasis) was not seen in any of the patients; however, one patient presented with persistent boggy swelling over the dorsum of foot for the last 18 months, which mimicked squamous cell carcinoma. Geographical distribution of these unusual presentations is given in [Table - 1]. Atypical presentations of cutaneous leishmaniasis are detailed in [Figure - 7].

Discussion

Symptomatic CL is diverse in its presentation and outcome. This clinical diversity is basically governed by parasite and host factors and immuno-inflammatory responses. [3] Clinically the wet (rural) type of the disease is more common in Baluchistan (southern province which borders with Iran and Afghanistan) and interior regions of Sindh province, while dry (urban) type is more prevalent in Punjab province, suggesting the presence of the two main strains of parasite (Leishmania major and leishmania tropica) in the country. [5],[9] Vast majority of our patients had dry (urban) type lesions, as the causative strain of parasite in these geographical regions was Leishmania tropica . Wet (rural type) lesions were only seen in patients who had a history of stay in or visit to, Baluchistan or Sindh province, where the prevalent strain was Leishmania major . We encountered a number of atypical variants of localized cutaneous disease. The proportion of these unusual morphologies was significantly higher in our study and the spectrum we observed was also greater than that seen in any of the previous studies. [5],[6],[7],[8] Unusual variants were seen in 5.7% of our patients. This was twice to what has been reported earlier by Raja et al , [5] Shams et al [7] and Calvopena et al . [8] We had 17 different atypical presentations. Some of these atypical variants were already described by Raja et al , [5] (paronychial, chancriform, annular, palmoplantar, zosteriform and erysipeloid) and more recently by Shams et al , [7] (paronychial, annular, eyelid, chancriform, zosteriform, palmoplantar, DLE-like and eczematous CL). Both of these studies were done in Baluchistan, while all of our patients belonged to central and northern Punjab and the northern areas of the country from where such atypical cases were not reported previously.

The commonest atypical pattern (34%) was lupoid leishmaniasis and surprisingly these were not very chronic cases of CL or the leishmaniasis recidivans as described in the past. They had duration of less than 1 year (mostly 4-8 months) and 12 out of the 14 cases were from the Kashmir region. In these patients the lesion started as small painless plaque on the nose or a side of the face, which progressively enlarged to involve most of the face in 2-3 months′ time. Ten of the 14 affected patients were females. This geographical restriction points towards the possibility of some different strains of parasite in the region or the altered host-immune response and predominance in females could be due to social or cultural factors (as most Kashmiri women work outdoors in fields and the face is the only uncovered part of the body apart from hands and feet).

Sporotrichoid pattern was restricted to wet type and was seen in patients who visited the endemic areas of Baluchistan or Sindh province. These nodules are thought to represent an immune reaction from direct lymphatic extension of leishmania organisms or antigens. [10],[11] Relative rarity of this pattern was due to the fact that a vast majority of our patients had dry type of lesion due to Leishmania tropica , where sporotrichoid spread is not commonly seen.

Most of the other atypical presentations, like paronychial, [6] whitlow, [6] lid, [12] scar, [13] palmoplantar [5] and chancriform, [5],[14] were probably related to the normal host response to the bite of the sandfly at these atypical sites. Verrucous, [15] psoriasiform, [5] erysipeloid, [5],[16] zosteriform, [5],[17] mycetomatous, [18] DLE-like, [7] squamous cell carcinoma-like [18] and eczematous [19] morphologies were likely to be due to some altered or over-expressed immune host responses. One case of mucocutaneous [20] disease in a child was probably due to local extension of the lesions over the lip and nose to the mucosal surfaces and was not due to different strain of the parasite. We did not see any patient with chronic recidivans lesions, [5] scalp lesions. [7] Recidivans cases were not encountered probably due to variable immune host response or different causative strain of parasite in the region. It may be a chance finding as recidivans cases had been reported earlier from Baluchistan. [5],[7] Similarly, no case of post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis, [21],[22] diffuse cutaneous leishmaniasis [23] and cutaneous disease in immunocompromised [23],[24] patient was encountered, possibly because of low prevalence of visceral leishmaniasis and AIDS.

Many of these atypical variants have already been described in literature, though very infrequently; but such a large spectrum with 17 different types of unusual morphologies was never described earlier. Moreover, the clinical spectrum was quite different compared to two other studies from the country. Most of the atypical morphologies were correctly diagnosed, keeping a high index of suspicion regarding the endemicity of the disease in the regions; but in a few cases, there was substantial delay, as in cases of chancriform, psoriasiform, zosteriform, erysipeloid, mycetoma and SCC-like lesions of CL. These were initially diagnosed as syphilitic chancre, psoriasis, herpes zoster, erysipelas, mycetoma and SCC; but it was after therapeutic unresponsiveness and/or further investigations that an ultimate diagnosis of atypical CL could be made. Response to treatment in these atypical cases encountered in the study was quite satisfactory.

Atypical clinical presentations of cutaneous leishmaniasis are increasingly seen in Pakistan and clustering of atypical cases in a geographically restricted region could possibly be due to a new parasite strain. To confirm this, further studies should be focused for species characterization in patients presenting with unusual morphology. It is further recommended that CL should be included in the differential diagnosis of common dermatological diseases like erysipelas, chronic eczema, herpes zoster, paronychia; and uncommon disorders like lupus vulgaris, squamous cell carcinoma, sporotrichosis, mycetoma and other deep mycoses.

| 1. |

Murray HW, Berman JD, Davies CR, Saravia NG. Advances in leishmaniasis. Lancet 2005;366:1561-77.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Rub MA, Azmi FA, Iqbal J, Hamid J, Ghafoor A, Burney MI, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Baluchistan: Reservoir hosts and sandfly vector in Uthal, Lasbella. J Pak Med Assoc 1986;36:134-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Grevelink SA, Lerner EA. Leishmaniasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 1996;34:257-72.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Lainson R, Shaw JJ. Evolution, classification and geographical distribution. In: Peters W, Killick-Kendrick R, editors. The leishmaniasis in biology and medicine. Academic Press: San Diego; 1987. p. 1-120.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Raja KM, Khan AA, Hameed A, Rahman S. Unusual clinical variants of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Pakistan. Br J Dermatol 1998;139:111-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Iftikhar N, Bari I, Ejaz A. Rare variants of cutaneous leishmaniasis: Whitlow, paronychia and sporotrichoid. Int J Dermatol 2003;42:807-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Shamsuddin S, Mengal JA, Gazozai S, Mandokhail ZK, Kasi M, Muhammad N, et al. Atypical presentation of cutaneous leishmaniasis in native population of Baluchistan. J Pak Assoc Dermatol 2006;16:196-200.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Calvopina M, Gomez EA, Uezato H, Kato H, Nonaka S, Hashiguchi Y. Atypical clinical variants in new world cutaneous leishmaniasis: Disseminated, erysipeloid and recidiva cutis due to leishmania panamensis. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2005;73:281-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Mujtaba G, Khalid M. Cutaneous leishmaniasis in Multan, Pakistan. Int J Dermatol 1998;37:843-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Walsh DS, Balagon MV, Abalos RM, Tiongco ES, Cellona RV, Fajardo TT, et al. Multiple lesions of cutaneous leishmaniasis in a Filipino expariate. J Am Acad Dermatol 1997;36:847-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Gaafar A, Fadl A, el Kadaro AY, el Hassan MM, Kemp M, Ismail AI, et al. Sporotrichoid cutaneous leishmaniasis due to Leishmania major of different zymodemes in the Sudan and Saudi Arabia: A comparative study. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1994;88:552-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Bari AU, Haq IU, Rani M. Lid leishmaniasis: An atypical clinical presentation. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2006;16:725-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Bari AU, Rahman SB. Scar Leishmaniasis. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2006;16:294-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Petit JH. Comparative trial of fine-particle griseofulvin in favus. Br J Dermatol 1962;74:62-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Criton S, Sridevi PK, Asokan PU. Lip leishmaniasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1995;61:303-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Elamin EM, Guerbouj S, Musa AM, Guizani I, Khalil EA, Mukhtar MM, et al. Uncommon clinical presentations of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Sudan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 2005;99:803-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Omidian M, Mapar MA. Chronic zosteriform cutaneous leishmaniasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2006;72:41-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Rahman SB, Bari AU. Morphological patterns of cutaneous leishmaniasis seen in Pakistan. J Pak Assoc Dermatol 2002;12:122-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Manzur A, Butt UA. Atypical cutaneous leishmaniasis resembling eczema on the foot. Dermatol Online J 2006;12:18.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Bari AU, Manzoor A. Mucocutaneous leishmaniasis: Does it really exist in Pakistan? J Pak Assoc Dermatol 2005;15:200-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Rawal RC, Bilimoria FE. Post kala azar dermal leishmaniasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1998;64:243-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Bittencourt A, Silva N, Straatmann A, Nunes VL, Follador I, Badaro R. Post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis associated with AIDS. Braz J Infect Dis 2003;7:229-33.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Khatri ML, Shafi M, Banghazil M. Cutaneous leishmaniasis with unusual presentation. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 1999;65:140-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Calza L, D'Antuono A, Marinacci G, Manfredi R, Colangeli V, Passarini B, et al. Disseminated cutaneous leishmaniasis after visceral disease in a patient with AIDS. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;50:461-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

5,804

PDF downloads

4,262