Translate this page into:

Nail avulsion: Indications and methods (surgical nail avulsion)

Correspondence Address:

Deepika Pandhi

Department of Dermatology and STD, University College of Medical Sciences and Associated Guru Teg Bahadur Hospital, University of Delhi, Delhi 110 095

India

| How to cite this article: Pandhi D, Verma P. Nail avulsion: Indications and methods (surgical nail avulsion). Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2012;78:299-308 |

Abstract

The nail is a subject of global importance for dermatologists, podiatrists and surgeons. Nail avulsion is a frequently undertaken, yet simple, intriguing procedure. It may either be surgical or chemical, using 40% urea. The former is most often undertaken using the distal approach. Nail avulsion may either be useful for diagnostic purposes like exploration of the nail bed, nail matrix and the nail folds and before contemplating a biopsy on the nail bed or for therapeutic purposes like onychocryptosis, warts, onychomycosis, chronic paronychia, nail tumors, matricectomy and retronychia. The procedure is carried out mostly under local anesthesia with or without epinephrine (1:2,00,000 dilution). Besides the above-mentioned indications, the contraindications and complications of nail avulsion are briefly outlined.Introduction

Nail avulsion, the separation of the nail plate from the surrounding structures, is the most frequently performed surgical or nonsurgical, chemical procedure on the nail unit. It may either be useful to explore the nail unit for diagnostic purposes or as a therapeutic tool in particular nail pathologies. Nail avulsion may be accomplished using either a distal or a proximal anatomical approach. The former is the most frequently used technique, in which the nail plate is released from its attachment from the nail bed at the hyponychium, [1] while in the latter, the nail plate is separated from the proximal nail fold (PNF) followed by a complete separation moving distally. [1] Chemical nail avulsion by using urea ointments is a valuable technique that avoids the complications encountered with its surgical counterpart. The current dissertation is an endeavour to bring about the salient briefs of the subject succinctly.

Applied Anatomy

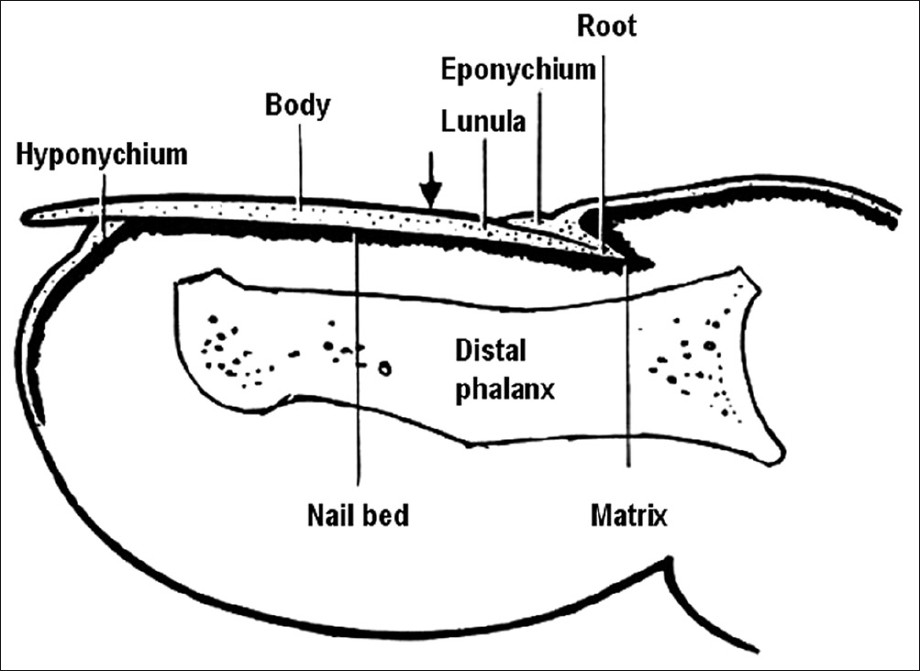

It is imperative to understand the anatomy of the nail and the intricacies of nail growth prior to undertaking nail avulsion. Nails are ectodermal appendages covering the dorsal aspects of the digits. [2]

These structures provide protection and integrity to the fingertip, in addition to facilitating skilled hand functions. Therefore, an abnormal alteration in the anatomy of the nail unit may interfere with the aforementioned functions. The distal border of the nail is free, while the proximal border is clutched into a fold and is covered with a skin flap called the eponychium or cuticle [Figure - 1]. The nail is attached at its lateral, distal and proximal borders. The nail bed, also called the sterile matrix, anchors the dermis to the periosteum of the distal phalanx. The matrix has been divided into distal sterile matrix (nail bed), which is covered with grown nail, intermediate matrix that corresponds to the epithelial lining of the ventral surface of the PNF, and the distal germinal matrix, from which a new nail arises. The germinal matrix is covered with the eponychium. [2]

|

| Figure 1: Anatomy of nail |

The lunula is the pale crescent-shaped structure easily recognized under the proximal portion of the nail. Importantly, the nail is not firmly attached at the lunula. Because the nail is formed in the germinal matrix, loss or deformity of this part results in permanent loss or permanent deformity of the nail. As the nail grows distally, the superficial cells become cornified. Distal to the lunula, the nail is firmly attached to the nail bed or sterile matrix. [2] Complete regrowth of an avulsed finger nail usually requires 4-5 months (1 mm/week), whereas the toe nail may require up to 10-12 months. It is essential to preserve the skin folds surrounding the nail margins. Wide scars or misalignment in the skin fold can result in splitting or permanent deformity of the nail when it regrows. Adhesions between the eponychium, nail bed and matrix are prevented by maintaining this space with either the replaced nail or gauze packing. The skin of the nail bed is supported by a highly vascularized subcutaneous layer that intimately links the nail bed to the dorsal periosteum of the distal phalanx. [3] The subungual glomus is a rich vascular network of microscopic vessels situated in the subcutaneous tissue deep to the nail bed, and plays a role in peripheral temperature regulation. Distal to the hyponychium and plantar to the medial and lateral nail folds (LNF), the digital pulp surrounds the distal phalanx and conveys vessels and nerves to and from the toe tip.

Indications of Nail Avulsion

Nail avulsion is the most common surgical procedure performed on the nail unit. The nail plate is excised from its prime attachments, the nail bed ventrally and the PNF dorsally. The indications of nail avulsion are outlined as follows:

Diagnostic

Nail avulsion is frequently undertaken as a preliminary step for the following indications: [4]

- Exploration of the nail bed and the nail matrix: This may be required in order to look for the pathologies originating in either the nail bed or the nail matrix, which include inflammatory dermatoses, infections, connective tissue diseases and tumors. On the other hand, a disease process affecting the surrounding tissues may encroach on the nail bed.

- Exploration of the PNF and the LNF: A complete exposure of these structures to divulge the extent of a disease may require a nail avulsion.

- Performing biopsy on the nail bed and the nail matrix: Many a times, nail avulsion is performed to uncover the nail bed and matrix for the purpose of a biopsy. This is often the situation in diseases like psoriasis, lichen planus, twenty nail dystrophy, nail unit tumors, nevi, melanonychia and pachyonychia congenita.

Therapeutic

Other than the aforementioned indications, nail avulsion is used as a therapeutic adjunct for the following indications:

- Before a chemical or surgical matricectomy: Matricectomy refers to the complete extirpation of the nail matrix, resulting in permanent nail loss. Usually, however, matricectomy is only partial, restricted to one or both lateral horns of the matrix. Nail ablation is the definitive removal of the entire nail organ. The most important common denominator in a successful matricectomy is the total removal or destruction of the matrix tissue. Matricectomy may be indicated for the management of onychauxis, onychogryphosis, congenital nail dystrophies and chronic painful nail, such as recalcitrant ingrown toenail or split within the medial or lateral one-third of the nail.

- Ingrown toe nail/onychocryptosis: Indications for the treatment of an ingrown toenail include significant pain or infection, onychogryphosis (a deformed and curved nail) or chronic, recurrent paronychia (inflammation of the nail fold). The most common procedure to treat locally infected ingrown toenails is partial avulsion of the lateral edge of the nail followed by chemical matricectomy using 80-88% phenol (phenolization). [5],[6] In a randomized study [7] comprising 117 patients, patients underwent partial nail avulsion in combination with either excision of the matrix or application of phenol, with or without local application of gentamicin afterwards. The measured endpoints were infection at 1 week and recurrence at 1 year. Infection rates were found unrelated to the use of antibiotics. However, recurrence rates were found to be significantly lower after phenolization of the nail bed (13.8%) compared with excision of the nail matrix (38.9%). Contrary to this, another randomized trial comprising 63 patients found both partial nail avulsion with phenolisation or with partial matricectomy to be equally effective. [8] Besides, a remarkably low incidence of recurrence (0.6%) and wound infection (2%) has been found. The mean time to return to normal activities is 2.1 weeks. [9]

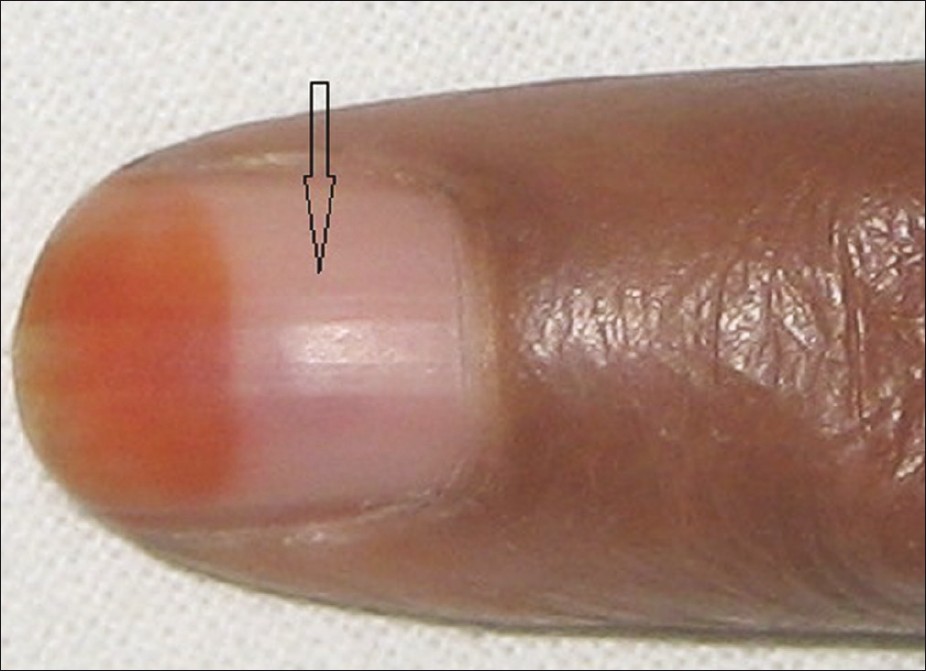

- Chronic onychomycosis: Thirteen patients with distal subungual onychomycosis in a total of 48 dermatophyte-infected nails were treated with chemomechanical, partial nail avulsion followed by topical miconazole for 8 weeks. Periungual skin irritation was common during the initial avulsion period. The clinical and mycological cure rate was 42% at 6 months after cessation of therapy. The therapeutic response was related to the pretreatment extension of subungual hyperkeratosis. This treatment modality could be a valuable alternative to other remedies for the treatment of onychomycosis limited to a few nails. [10] Total nail avulsion has been found to be effective, especially for patients with single- or oligo-onychomycosis [Figure - 2] and in those with a dubious diagnosis. [11] In contrast, another randomized trial comprising 40 subjects with single-nail onychomycosis recorded a high drop-out rate. All cases of total dystrophic onychomycosis failed to respond to this therapy. Overall, 15 of 27 (56%) patients were cured with this approach. No side-effects or long-term complications of the nail avulsion were encountered. [12]

-

Figure 2: Distal subungual onychomycosis involving a single nail with evidence of onychogryphosis - Traumatic nail injuries: Avulsion may be used to evaluate the stability of the nail bed or to release a subungual hematoma after failed puncture aspiration. If sufficient blunt or sharp force is applied to the nail plate and surrounding folds, it can violate the structural integrity of the nail bed and the resultant hemorrhage can fill the potential space that normally exists between the nail plate and the underlying nail bed. The force of the injury as well as the hemorrhagic response can separate the nail plate from the bed, causing traumatic onycholysis. If the force is sufficient enough, the proximal margin of the plate will often separate from the matrix region under the PNF and elevate through the nail fold. This disrupts the seal of the cuticle and potentially exposes the underlying tissues to bacterial contamination. If there is an associated fracture, the patient may be at risk for distal phalangeal osteomyelitis. [13] Whenever a patient presents with an acutely injured, throbbing toe with a subungual hematoma, one should consider disruption of the nail plate. If the patient maintains structural integrity of the nail folds and there is disruption of the nail bed, subungual pressure secondary to hemorrhage can cause persistent digital pain that may last for several hours to several days, and simply draining the hematoma will usually provide relief. There are many ways to drain a painful subungual hematoma safely. The method one uses is based on the structural integrity of the nail folds and the amount of the visible nail plate associated with the hematoma. As a rule, when there are stable nail folds and an injury displaying less than 25% of the visible nail plate associated with the hematoma, one can drain the hematoma through the nail plate. [14] If the subungual hematoma involves greater than 25% of the visible nail plate and/or the nail plate has been avulsed in such a way as to disrupt the proximal, medial or LNF contiguous with the bed, then a significant nail bed laceration is likely. Accordingly, one should remove the entire plate in order to facilitate direct visualization and surgical repair of the nail bed. Severe stabbing or plantar flexor injuries can cause nail bed laceration and phalangeal fractures that propagate along the dorsal surface of the nail plate into the PNF and through the physeal plate of the distal phalanx, separating the nail plate from the ventral surface of the PNF. [15] When this occurs, the basilar epiphysis is usually displaced dorsal relative to the nail bed because the epiphysis remains anchored to the interphalangeal collateral ligaments and the extensor tendon. [16] One would treat this injury by removing the nail plate or at least the proximal portion of the nail plate and following-up with cleansing, debridement and inspection.

- Chronic paronychia: It is an extremely recalcitrant dermatosis that is particularly prevalent in housewives. Medical treatment for this condition is unsatisfactory in a significant number of cases. [17] In these patients, no response is evident to irritant avoidance and topical therapy and surgical approach forms a vital part of management. An en bloc excision of the PNF combined with a total, or more commonly partial, restricted to the base of the nail plate, nail plate avulsion has been shown to be a useful method in chronic, recalcitrant paronychia, especially where the PNF is fibrosed or thickened. [17] Alternatively, an eponychial marsupialization, with or without nail removal, may be performed. This technique involves excision of a semicircular skin section proximal to the nail fold and parallel to the eponychium, expanding to the edge of the nail fold on both sides. [18]

- Retronychia: It is defined as a reverse embedding of the nail plate into the PNF, a result of persistent nail fold inflammation. Nail plate avulsion with supplementary medical management is curative. [19]

- Pincer nails ("Omega nails" and "Trumpet nails"; [Figure - 3]): A toenail disorder in which the lateral edges of the nail slowly approach one another compressing the nailbed and the underlying dermis. It occurs less often in the fingernails and is usually asymptomatic. Pincer nails are not amenable to surgical nail techniques as these do not affect the underlying bony alterations, which is the primary pathology. Repeated nail avulsion at regular intervals using 40% urea was found to be effective in a 39-year-old woman with hereditary pincer nails. [20] Persistent pincer nail deformity was also effectively treated with nail avulsion and CO 2 laser matricectomy in a 63-year-old man. [21] However, caution is warranted as repeated surgical nail avulsions may worsen the curvature of nails and further increase the transverse curvature of hallux nails. [22] Widening of the nail bed followed by splinting has recently been recommended. [23] Nonetheless, complete surgical nail ablation or phenolisation is the only ultimate remedy for pincer nails. Nail avulsion followed by osteophyte removal and broadening the nail bed has also been claimed to be effective. [22]

-

Figure 3: Pincer nail - Warts: It is the most common nail tumor, and mostly affects children and young adults. Periungual warts [Figure - 4] are usually due to HPV-1, 2 and 4. Development of periungual warts is favored by maceration and trauma, especially nail biting. The natural course of warts restricts aggressive approaches to selected cases. Partial or complete nail avulsion is indicated for exploring the extent of involvement of nail bed or matrix with HPV and also to ensure complete eradication of diseased tissue. Medical treatments, usually topical, include keratolytic agents, virucidal agents and immunomodulators. All choices have been utilized successfully, but keratolytic agents are the best first-line approach. Surgical treatments include cryotherapy, surgical excision, electrosurgery, infrared coagulation, localized heating with a radiofrequency heat generator and laser therapy, especially the Er: YAG laser. Recalcitrant periungual verrucae (24 lesions) in 17 patients were vaporized with the carbon dioxide laser in combination with partial or complete nail avulsion. [24] A complete cure rate of 71% was observed in patients who had one or two treatments. The cure rate increased to 94% in patients who underwent one or two laser treatments in combination with other therapies. Postoperative pain was short lived and infection and significant onychodystrophy were uncommon.

-

Figure 4: Wart on the lateral nail fold encroaching on nail bed and matrix resulting in destruction of the nail plate. Partial nail avulsion is indicated to determine the extent of the wart -

Tumors: Nail plate avulsion combined with nail bed excision forms the treatment for the following tumors:

- Onychomatricoma: It is a rare nail matrix tumor with specific clinical and histologic features, including a macroscopic appearance of filiform digitations originating from the nail matrix that are inserted in the nail plate. [25] Onychomatricoma has a classical clinical appearance; however, it is difficult to identify, as it is not until surgery, when the typical filiform projections are more visible that the diagnosis can be made. [26]

- Glomus tumor [Figure - 5]: It is a painful subcutaneous nodule, commonly occurring in the subungual regions, and is accompanied by tenderness and temperature sensitivity. In the treatment of subungual glomus tumor, surgical excision is known to be the only curative method. It is challenging to minimize postoperative nail deformity and yet to ensure a low incidence of tumor recurrence. [27] The transungual approach with nail avulsion and an incision selected according to the tumor location can produce an excellent outcome with minimal postoperative complications. Dressing with a trimmed nail plate may also be beneficial in managing the wound. [28]

- Miscellaneous: Melanoma and nonmelanoma cancers, pyogenic granuloma, fibrokeratoma and exostoses are the other tumors that may require a nail avulsion as a preliminary procedure. [3]

Figure 5: Distal nail plate showing henna staining and intensely painful dusky erythematous lesion (arrow) under the nail plate, which was diagnosed as Glomus tumor

Contraindications

Relative contraindications to performing surgery in the nail unit are outlined as follows [3] :

- Peripheral vascular disease

- Collagen vascular disease

- Diabetes mellitus

- Disorders of hemostasis

- Acute infection or inflammation of the nail unit, including the surrounding paronychial tissues

Procedures of Nail Avulsion

Distal [3],[29],[30],[31] and proximal avulsion are the two surgical approaches for undertaking nail avulsion. [29],[32] Chemical avulsion with urea paste is another valid nonsurgical technique that may be used in certain situations. A partial or complete nail avulsion can be performed, depending on the location and extent of disease. Nail avulsion, however, is not a definitive cure in cases of nail dystrophy caused by onychocryptosis, nail matrix disease [33] or extensive nail bed pathology.

Anesthesia

Before avulsion, anesthesia of the digit is achieved through a digital block performed with 1% lidocaine. [34]

There are two schools of thought on the use of epinephrine with lidocaine in the context of digital anesthesia. By convention, when administering an anesthetic for nail surgery, the use of epinephrine should be avoided, especially in patients with a history of extensive vascular disease. Therefore, patients with a history of thrombotic or vasospastic disease and uncontrolled hypertension should not receive epinephrine. [3] Epinephrine has vasoconstricting properties, and it has been associated with necrosis and poor wound healing of tissues, while others believe that these complications appear to be mostly theoretical and have rarely been noted to occur in practice. Proper injection technique and adequate selection of patients are recommended to minimize complications. A concentration of 1:2,00,000 is deemed as safe. Indeed, in a study, epinephrine-supplemented local anesthetics were used for the ear and nose surgery without any significant complications in more than 10,000 surgical procedures. [35] Further, skin blood flow was studied at the fingerpads via laser Doppler flowmetry over the course of 24 h in a prospective, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study with 20 vascularly healthy test persons. It was shown that adrenaline additive in local anesthesia decreased blood flow by less than 55% after a period of 16 min. [36] In yet another study, there were 3110 consecutive cases of elective injection of low-dose epinephrine (1:100,000 or less) in the hand and fingers and no instance of digital tissue loss was documented. [37] In fact, a total of 50 cases of digital gangrene have been documented in the literature, of which 21 were associated with the use of epinephrine; however, this was prior to 1950, when procaine was used as an anesthetic and the concentration of epinephrine used was high. The adrenaline digital infarction cases that created the dogma are invalid because they were also injected with either procaine or cocaine, which were both known to cause digital infarction on their own, and none of the 21 adrenaline infarction cases had an attempt at phentolamine rescue. [38] In fact, the addition of epinephrine reduces the need for the use of tourniquets and large volumes of anesthetic and provides a better and longer pain control during digital procedures. Exsanguinating tourniquet may be used to minimize bleeding; however, it should be released every 15 min for a few minutes to prevent gangrene. [39]

Various methods have been suggested to reduce the pain while injecting a local anesthetic. Addition of sodium bicarbonate reduces the stinging sensation related to the acidic nature of adrenaline containing local anesthetic. Sedation with a combination of sedatives, analgesics and tranquilizers is helpful. This places the patient in a quiescent state so that local anesthetic and nerve blocks may be comfortably administered. In addition, repetitive, rapid pinching and shaking of the skin proximal to the site of injection during lignocaine infiltration works on the "gate control hypothesis." [40]

Methods

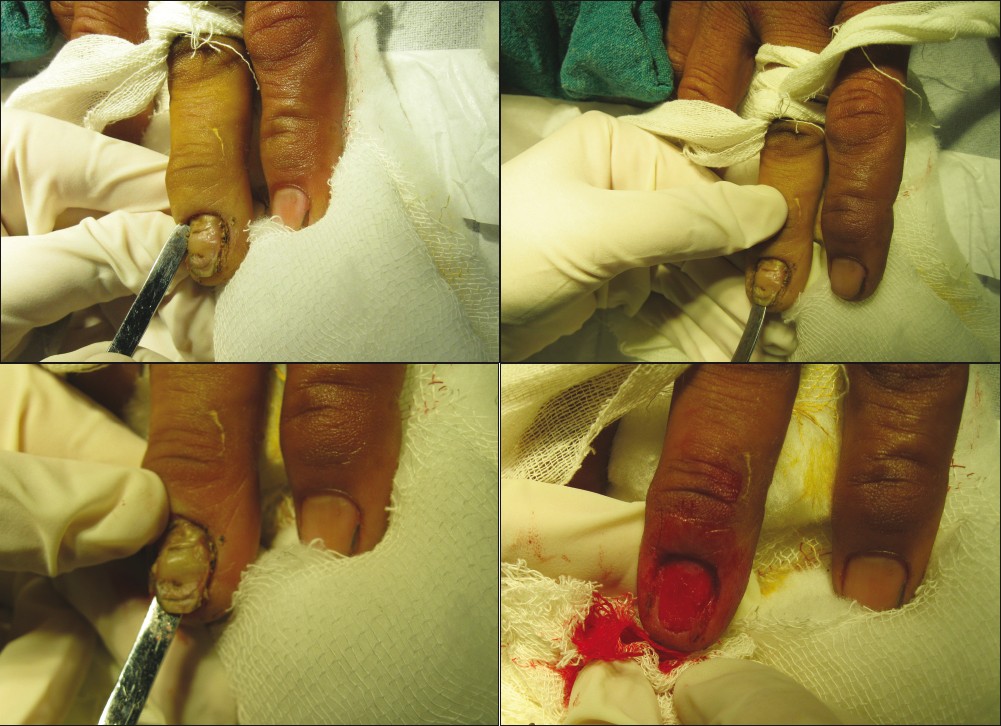

Nail avulsion surgery is frequently accomplished using a nail elevator device. In addition, a mosquito hemostat or a dental spatula may also be used for the purpose. In distal nail avulsion [Figure - 6]a-d, the instrument is introduced under the distal free edge of the nail plate so that the nail plate can be separated from the underlying nail bed hyponychium. The nail plate is then separated from the underlying nail bed directed proximally towards the matrix, with significant resistance occurring until the matrix is reached. As the matrix is reached, the surgeon experiences a sudden decrease in resistance. Subsequently, the elevator [Figure - 7] is reinserted with several longitudinal and side to side strokes to detach the nail plate from the nail bed totally. Thereafter, the elevator is inserted under the PNF in the proximal nail groove between the eponychium and the nail plate to release the attachment. This step should be a gentle one so as to avoid inadvertent injury. [33]

|

| Figure 6a: Distal nail avulsion in a case of chronic paronychia with proximal nail fold fibrosis and dystrophic nail plate. The plate is being avulsed in addition to crescentic excision of the proximal nail fold Figure 6b: Freeing of the lateral nail fold Figure 6c: Lifting of the nail plate from the nail bed with lateral sweeping movement Figure 6d: Vascular nail bed after separation of the nail plate |

|

| Figure 7: Freer's elevator |

Proximal nail avulsion is preferred in the presence of distal nail dystrophy, in which it is often not possible to access the distal free edge of the nail plate. This situation is often encountered in distal subungual onychomycosis. [29],[32],[41] The Freer elevator is inserted beneath the cuticle in the proximal groove to separate the PNF from the nail plate. Then, it is reoriented so as to allow its concave surface to accommodate the curved surface of the ventral surface of the nail plate. [42] The instrument is advanced until it finally reaches the distal edge of the nail plate.

Secondary bacterial infections can be a cause of considerable morbidity in nail avulsion, especially in toe nails. Intraoperative antiseptic nail irrigation has, therefore, been recommended to reduce bacterial contamination. [43]

Alternatives to the aforementioned nail avulsion methods have been described. In many cases, partial nail plate avulsion is preferable compared with traditional total distal and proximal plate avulsions. The techniques described herein include partial distal, lateral, proximal and window techniques and two variations of the total plate avulsion termed the trap door and lateral nail plate curl avulsion. [44] By using these methods, the surgeon is able to access the targeted nail unit while minimizing trauma to the adjacent, uninvolved tissue.

Chemical nail avulsion

Forty percent urea ointment is often used in the treatment of onychomycosis, onychogryphosis, psoriasis and candidal and bacterial infections. [45],[46],[47] Urea ointment paste is formulated to include 40% urea, 5% white beeswax or paraffin, 20% anhydrous lanolin and 35% white petrolatum. [45],[46] Urea acts by dissolving the bond between the nail bed and the nail plate, and it also softens the nail plate. The paronychial area is protected with adhesive tape before applying urea paste to prevent chemical irritation of the soft tissues. The ointment is liberally applied to the nail plate, and hypoallergenic tape is used to create a well around the treated thickened nail to hold the paste. [47] The patient is instructed to keep the nail occluded and to avoid wetting the treated area. After 1 week of occlusion, the dystrophic nail is removed by using a nail elevator and a nail clipper. In onychomycosis, antifungals may be prescribed as an adjunct. However, surgical nail avulsion followed by topical antifungal therapy cannot be recommended for the treatment of onychomycosis as it is often associated with a high dropout rate and poor compliance. [12] Dystrophic nails may respond better to chemical avulsion, and it is the ideal management for symptomatic dystrophic nails in patients with diabetic neuropathy, vascular disease or immunosuppression. [45] In addition, chemical avulsion may be used as a palliative, pain-relieving therapy in onychogryphosis. Minimal to absent pain, a low risk of infection, hemorrhage and lesser downtime are the advantages of chemical over surgical avulsion. [45] Requirement of prolonged application and irritation are some disadvantages of the procedure. Further, patients with gross thickening of the nail without significant nail dystrophy may respond poorly to chemical avulsion due to poor penetration. [45] Superficial abrasion of the nail plate may be worthwhile to foster the penetration of urea. Contamination with water and poor occlusion may lead to treatment failure. Preparations other than 40% urea have also been tried. A combination of 20% urea and 10% salicylic acid ointment under a 2-week occlusion has been effectively used for minimally dystrophic nails. [30] Besides, a nail lacquer formulation containing 40% urea in a film-forming solution has been devised. In a study comprising 10 patients of onychomycosis, the urea nail lacquer was applied with a brush twice a day for 1 week by the patient and for a further week in two patients presenting with total dystrophic onychomycosis. This facilitated easy removal of nail and was well tolerated. [48] In another study comprising of 13 patients of onychomycosis, a solution of 1% fluconazole and 20% urea in a mixture of ethanol and water applied once daily at bedtime showed a favorable response. [49] Phenolization is a well-conceived method of chemical matricectomy. In this procedure, 88% phenol is applied to the nail matrix while care is taken to avoid contamination with any ointment applied in the vicinity. It may be applied in three cycles of 30 s each. Phenol has to be applied with the tourniquet on, so as to ensure a bloodless field, as blood is known to inactivate phenol. Finally, phenol is neutralised with isopropyl alcohol and an appropriate dressing is done. [50] In a randomized study conducted on 148 ingrowing nails (grade 2-3) of 110 patients, 1-min phenol cauterization of the germinal matrix was found to have a better safety profile than prolonged applications in the treatment of ingrown nails. [51] Unpredictable tissue damage and prolonged healing time are the disadvantages of phenolization. Recently, the partial avulsion of the affected edge and treatment of the germinal matrix for 1 min with 10% sodium hydroxide preceded by matrix curettage has been found to be an effective and safe treatment modality for ingrown toenails in people with diabetes. [52]

Sodium hydroxide is an alternative chemical agent that has been claimed to cause less tissue damage as compared to phenol. Matricectomy with 10% sodium hydroxide, either applied for 2 min or 1 min combined with curettage, is equally effective in the treatment of ingrowing toenails with high success rates and minimal postoperative morbidity. [53] In a study comprising 46 patients, 154 ingrowing nail sides were treated with either sodium hydroxide or phenol matricectomy. Both sodium hydroxide and phenol were found to be effective giving high success rates, but sodium hydroxide caused less postoperative morbidity and provided faster recovery. [54]

Laser nail avulsion

The use of carbon dioxide laser has recently been well described. A 63-year-old man was evaluated and treated with the carbon dioxide laser for a persistent pincer nail deformity. The patient tolerated the procedure well and had an acceptable surgical outcome. [21] In another study, 196 consecutive patients previously unsuccessfully treated by surgery underwent successful CO 2 laser (5 W, defocused 2 mm beam in continuous mode) surgery for recurrent onychocryptosis. [55] Partial nail avulsion followed by matricectomy with pulse CO 2 laser in the treatment of ingrown toenails resulted in a high cure rate, short postoperative pain duration and low risk of infection. [56] Recalcitrant periungual verrucae (24 lesions) in 17 patients were successfully treated with CO 2 laser vaporization. [57] Vaporization of these warts, in combination with partial or complete nail avulsion, resulted in complete cures in 71% of the patients who underwent one or two treatments. Infection and significant onychodystrophy were uncommon. Pain was largely short lived. Thus, laser therapy in combination with nail avulsion improves the therapeutic outcome and reduces complications.

Postoperative care

Meticulous postoperative care is essential for a successful nail avulsion. A nonadherent, highly absorbant dressing is ideal. It may be kept in place with either an elastoplast or a paper tape. The latter is less sticky and convenient to remove. The lateral grooves may be studded with either a paraffin gauze or an antibiotic tulle. [1],[3],[4] Dressing may be removed after 24 h after soaking in warm water or saline. It is an acceptable practice to soak the operated area in warm water twice a day. In addition, the povidone-iodine solution application may promote the healing process. The patient should be advised to keep the operated limb elevated so as to minimize the pain and swelling. Besides, minimal activity with the involved limb, especially if toenails are avulsed, should be carried out for at least 2 weeks.

Complications

Complications are seldom encountered in nail avulsion. These largely result from nail matrix damage and present with postoperative nail deformity. Pain is the most common complication following nail avulsion. It is usually of short duration and responds well to analgesics. [58] Allergy to anesthetic, minor wound discharge, infection, hematoma, nail deformity, malalignment, nail impaction (distal embedding), local spicule growth and persistent pain and swelling are the other adverse sequelae. Complications may be avoided by adequate preventive measures, such as judicious patient selection, aseptic technique and gentle handling of the nail matrix. [59]

Conclusion

Nail avulsion is a subject that has not been paid attention to by dermatologists. One needs to be well-versed with the anatomy of the nail while undertaking a nail avulsion to avoid matrix and nail fold injury. Total nail avulsion has been the conventional method to deal with various nail unit pathologies; however, partial avulsion has gained popularity due to its simplicity and fewer postoperative complications. Ingrown toe nail, chronic onychomycosis and periungual warts continue to be the most common indications for nail avulsion. Careful patient selection and maintenance of asepsis during and after the procedure and gentle handling of matrix and nail folds are the key to superior outcomes of the procedure.

| 1. |

Siegle RJ, Swanson NA. Nail surgery: A review. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1982;8:659-66.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Haneke E. Surgical anatomy of the nail apparatus. Dermatol Clin 2006;24:291-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Scher RK. The nail. In: Roenigk RK, Roenigk HH, Ratz JL, editors. Dermatologic Surgery-Principles and Practice. 2 nd ed. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2006. p. 281-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Clark RE, Madani S, Bettencourt MS. Nail surgery. Dermatol Clin 1998;16:145-64.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Zuber TJ. Ingrown toenail removal. Am Fam Physician 2002;65:2547-52.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Rounding C, Bloomfield S. Surgical treatments for ingrowing toenails. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;18: CD001541.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Bos AM, van Tilburg MW, van Sorge AA, Klinkenbijl JH. Randomized clinical trial of surgical technique and local antibiotics for ingrowing toenail. Br J Surg 2007;94:292-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Gerritsma-Bleeker CL, Klaase JM, Geelkerken RH, Hermans J, van Det RJ. Partial matrix excision or segmental phenolization for ingrowing toenails. Arch Surg 2002;137:320-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Shaikh FM, Jafri M, Giri SK, Keane R. Efficacy of wedge resection with phenolization in the treatment of ingrowing toenails. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2008;98:118-22.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Rollman O. Treatment of onychomycosis by partial nail avulsion and topical miconazole. Dermatologica 1982;165:54-61.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Lai WY, Tang WY, Loo SK, Chan Y. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of patients undergoing nail avulsion surgery for dystrophic nails. Hong Kong Med J 2011;17:127-31.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Grover C, Bansal S, Nanda S, Reddy BS, Kumar V. Combination of surgical avulsion and topical therapy for single nail onychomycosis: A randomized controlled trial. Br J Dermatol 2007;157:364-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Fox IM. Osteomyelitis of the distal phalanx following trauma to the nail: A case report. J Amer Podiatric Assoc 1992;82:542-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Tucker DJ, Jules KT, Raymond F. Nailbed injuries with hallucal phalangeal fractures-evaluation and treatment. J Amer Podiatric Assoc 1996;86:170-3

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Banks AS, Cain TD, Ruch JA. Physeal fractures of the distal phalanx of the hallux. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 1988;78:310-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Hashizume H, Nishida K, Mizumoto D, Takagoshi H, Inoue H. Dorsally displaced epiphyseal fracture of the phalangeal base. J Hand Surg Br 1996;21:136-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Grover C, Bansal S, Nanda S, Reddy BS, Kumar V. En bloc excision of proximal nail fold for treatment of chronic paronychia. Dermatol Surg 2006;32:393-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Bednar MS, Lane LB. Eponychial marsupialization and nail removal for surgical treatment of chronic paronychia. J Hand Surg Am 1991;16:314-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

de Berker DA, Richert B, Duhard E, Piraccini BM, André J, Baran R. Retronychia: Proximal ingrowing of the nail plate. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;58:978-83.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

el-Gammal S, Altmeyer P. Successful conservative therapy of pincer nail syndrome. Hautarzt 1993;44:535-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Lane JE, Peterson CM, Ratz JL. Avulsion and partial matricectomy with the carbon dioxide laser for pincer nail deformity. Dermatol Surg. 2004;30:456-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Baran R, Haneke E, Richert B. Pincer nails: Definition and surgical treatment. Dermatol Surg 2001;27:261-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Ghaffarpour G, Tabaie SM, Ghaffarpour G. A new surgical technique for the correction of pincer-nail deformity: Combination of splint and nail bed cutting. Dermatol Surg 2010;36:2037-41.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Street ML, Roenigk RK. Recalcitrant periungual verrucae: The role of carbon dioxide laser vaporization. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990;23:115-20.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Goutos I, Furniss D, Smith GD. Onychomatricoma: An unusual case of ungual pathology: Case report and review of the literature. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg 2010;63:e54-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Estrada-Chavez G, Vega-Memije ME, Toussaint-Caire S, Rangel L, Dominguez-Cherit J. Giant onychomatricoma: Report of two cases with rare clinical presentation. Int J Dermatol 2007;46:634-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Song M, Ko HC, Kwon KS, Kim MB. Surgical treatment of subungual glomus tumor: A unique and simple method. Dermatol Surg 2009;35:786-91.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Moon SE, Won JH, Kwon OS, Kim JA. Subungual glomus tumor: Clinical manifestations and outcome of surgical treatment. J Dermatol 2004;31:993-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 29. |

Siegle RJ, Swanson NA. Nail surgery: A review. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1982;8:659-66.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 30. |

Zook EG, Baran R, Haneke E, Dawber RPR. Nail surgery and traumatic abnormalities In: Baran R, Dawber RP, de Berker DA, Haneke E, Tosti A, editors. Diseases of the Nails and their Management 3 rd ed. UK: Blackwell Science Ltd; 2001. p. 425-514.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 31. |

Scher RK. Surgical avulsion of nail plates by a proximal to distal technique. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1981;7:296-7

[Google Scholar]

|

| 32. |

Scher RK. Nail surgery. Clin Dermatol 1987;5:135-42.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 33. |

Albom MJ. Avulsion of a nail plate. J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1977;3:34-5

[Google Scholar]

|

| 34. |

Denkler K. A comprehensive review of epinephrine in the finger: To do or not to do. Plast Reconstr Surg 2001;108:114-24.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 35. |

Häfner HM, Röcken M, Breuninger H. Epinephrine-supplemented local anesthetics for ear and nose surgery: Clinical use without complications in more than 10,000 surgical procedures. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2005;3:195-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 36. |

Häfner HM, Schmid U, Moehrle M, Strölin A, Breuninger H. Changes in acral blood flux under local application of ropivacaine and lidocaine with and without an adrenaline additive: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 2008;38:279-88.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 37. |

Lalonde D, Bell M, Benoit P, Sparkes G, Denkler K, Chang P. A multicenter prospective study of 3,110 consecutive cases of elective epinephrine use in the fingers and hand: The Dalhousie Project clinical phase. J Hand Surg Am 2005;30:1061-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 38. |

Thomson CJ, Lalonde DH, Denkler KA, Feicht AJ. A critical look at the evidence for and against elective epinephrine use in the finger. Plast Reconstr Surg 2007;119:260-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 39. |

Krunic AL, Wang LC, Soltani K, Weitzul S, Taylor RS. Digital anesthesia with epinephrine: An old myth revisited. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;51:755-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 40. |

Mutalik S. How to make local anesthesia less painful? J Cut Aesth Surg 2008;1:37-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 41. |

Jellinek NJ. Nail surgery: Practical tips and treatment options. Dermatol Ther 2007;20:68-74.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 42. |

Clark RE, Madani S, Bettencourt MS. Nail surgery. Dermatol Clin 1998;16:145-64.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 43. |

Becerro de Bengoa Vallejo R, Losa Iglesias ME, Cervera LA, Fernández DS, Prieto JP. Efficacy of intraoperative surgical irrigation with polihexanide and nitrofurazone in reducing bacterial load after nail removal surgery. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;64:328-35.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 44. |

Collins SC, Cordova K, Jellinek NJ. Alternatives to complete nail plate avulsion. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;59:619-26.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 45. |

South DA, Farber EM. Urea ointment in the nonsurgical avulsion of nail dystrophies: A reappraisal. Cutis 1980;25:609-12.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 46. |

White MI, Clayton YM. The treatment of fungus and yeast infections of nails by the method of "chemical removal'. Clin Exp Dermatol 1982;7: 273-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 47. |

Averill RW, Scher RK. Simplified nail taping with urea ointment for nonsurgical nail avulsion. Cutis 1986;38:231-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 48. |

Baran R, Tosti A. Chemical avulsion with urea nail lacquer. J Dermatolog Treat 2002;13:161-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 49. |

Baran R, Coquard F. Combination of fluconazole and urea in a nail lacquer for treating onychomycosis. J Dermatolog Treat 2005;16:52-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 50. |

Bostanci S, Ekmekçi P, Gürgey E. Chemical matricectomy with phenol for the treatment of ingrowing toenail: A review of the literature and follow-up of 172 treated patients. Acta Derm Venereol 2001;81:181-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 51. |

Tatlican S, Yamangöktürk B, Eren C, Eskioðlu F, Adiyaman S. Comparison of phenol applications of different durations for the cauterization of the germinal matrix: An efficacy and safety study. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2009;43:298-302

[Google Scholar]

|

| 52. |

Tatlican S, Eren C, Yamangokturk B, Eskioglu F, Bostanci S. Chemical matricectomy with 10% sodium hydroxide for the treatment of ingrown toenails in people with diabetes. Dermatol Surg 2010;36:219-22.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 53. |

Ozdemir E, Bostanci S, Ekmekci P, Gurgey E. Chemical matricectomy with 10% sodium hydroxide for the treatment of ingrowing toenails. Dermatol Surg 2004;30:26-31.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 54. |

Bostanci S, Kocyigit P, Gurgey E. Comparison of phenol and sodium hydroxide chemical matricectomies for the treatment of ingrowing toenails. Dermatol Surg 2007;33:680-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 55. |

Serour F. Recurrent ingrown big toenails are efficiently treated by CO2 laser. Dermatol Surg 2002;28:509-12

[Google Scholar]

|

| 56. |

Yang KC, Li YT. Treatment of recurrent ingrown great toenail associated with granulation tissue by partial nail avulsion followed by matricectomy with sharpulse carbon dioxide laser. Dermatol Surg 2002;28:419-21.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 57. |

Street ML, Roenigk RK. Recalcitrant periungual verrucae: The role of carbon dioxide laser vaporization. J Am Acad Dermatol 1990;23:115-20

[Google Scholar]

|

| 58. |

Lai WY, Tang WY, Loo SK, Chan Y. Clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes of patients undergoing nail avulsion surgery for dystrophic nails. Hong Kong Med J 2011;17:127-31.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 59. |

Moossavi M, Scher RK. Complications of nail surgery: A review of the literature. Dermatol Surg 2001;27:225-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

88,644

PDF downloads

6,190