Translate this page into:

Optimizing Q-switched lasers for melasma and acquired dermal melanoses

Correspondence Address:

Sanjeev Jayanth Aurangabadkar

Aurangabadkar, Skin and Laser Clinic, 1st Floor, Brij Tarang, Green Lands, Begumpet, Hyderabad - 500 016, Telangana

India

| How to cite this article: Aurangabadkar SJ. Optimizing Q-switched lasers for melasma and acquired dermal melanoses. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2019;85:10-17 |

Abstract

The Q-switched Nd:YAG laser is an established modality of treatment for epidermal and dermal pigmented lesions. The dual wavelengths of 1064nm and 532nm are suited for the darker skin tones encountered in India. Though this laser has become the one of choice for conditions such as nevus of Ota, Hori's nevus and tattoos, its role in the management of melasma and other acquired dermal melanoses is not clear. Despite several studies having been done on the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser in melasma, there is no consensus on the protocol or number of sessions required. Acquired dermal melanoses are heterogenous entities with the common features of pigment incontinence and dermal melanophages resulting in greyish macular hyperpigmentation. This article reviews the current literature on laser toning in melasma and the role of the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser in stubborn pigmentary disorders such as lichen planus pigmentosus. As the pathology is primarily dermal or mixed epidermal-dermal in these conditions, the longer wavelength of 1064nm is preferred due to its deeper penetration. Generally multiple sessions are needed for successful outcomes. Low fluence Q-switched Nd:YAG laser at 1064nm utilizing the multi-pass technique with a large spot size has been suggested as a modality to treat melasma. Varying degrees of success have been reported but recurrences are common on discontinuing laser therapy. Adverse effects such as mottled hypopigmentation have been reported following laser toning; these can be minimized by using larger spot sizes of 8 to 10mm with longer intervals (2 weeks) between sessions.

Introduction

Disorders of pigmentation causing considerable social and psychological distress to patients are often encountered in clinical practice. Pigmentary conditions can be classified based on the location of pigment as epidermal, dermal and mixed epidermal-dermal lesions.[1] This rough classification is important as it dictates the choice of therapy. Epidermal lesions such as freckles, lentigines and café au lait macules are classical in presentation and have a predictable response to treatment.[2] The other two categories tend to be less distinct and generally have a variable response to laser therapy.

Dermal melanosis can be broadly divided into two categories – congenital or acquired. Nevus of Ota, nevus of Ito, blue nevus and Mongolian spots are congenital in nature but nevus of Ota can appear later in life.[3] Hori's nevus (acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules), dermal melasma and lichen planus pigmentosus are typically acquired later in life. Histologically, these lesions have melanin granules in the dermis, in melanophages or in nevoid cells.[4] Dermal melanoses are challenging in that they seldom respond to topical medical therapy or aesthetic procedures such as superficial peels. Lasers have played a significant role in the management of these conditions due to their precise selectivity, depth of penetration and the ability to spare the epidermis.[5]

Q-Switched Nd:YAG Laser-Tissue Interaction

The Q-switched Nd:YAG laser is the laser of choice for dealing with dermal and mixed epidermal-dermal pigmented lesions, particularly in dark skin.[6] The laser's ability to specifically target melanosomes in melanocytes, keratinocytes and melanophages, its ultra-short pulse width (in nanoseconds) and adjustable spot size are key factors that allow effective targeting of dermal pigment.[7] Depth of penetration and selectivity are functions of the wavelength of a laser. The Q-switched Nd:YAG laser has two wavelengths – a longer wavelength of 1064 nm and a shorter wavelength of 532 nm. The longer wavelength of 1064 nm is ideal for dermal lesions due to its deeper penetration and poor absorption in epidermal melanin.[8] These lasers have a large spot size up to 10 mm, which also allows deep penetration of the laser beam. Depth of penetration is directly proportional to the spot size of the beam, as more photons are likely to remain within the area.[6] The mechanism of action of these lasers includes both a photothermal effect and photomechanical/photoacoustic phenomenon that is based on the principle of selective photothermolysis.[8] To achieve successful outcomes and minimize side effects, it is necessary for the laser to have a “top-hat” beam profile where uniform energy is distributed over a given spot size area without producing undue “hot spots.” Of late, a fractional handpiece has also become available for some Q-switched Nd:YAG laser systems, wherein the laser beam is split into microbeams, delivering laser energy to a part or fraction of the area treated.[9] The fractional handpiece is primarily used for rejuvenation, rhytides and pigmentary conditions such as melasma.

Approach to Laser Treatment in Darker Skin

Treating pigmentary disorders in dark skin requires some precautions to attain best results.[1] These include:

- Strict sun-protective clothing and use of broad-spectrum sunscreens of SPF at least 30 and PA +++ prior to starting laser treatment and throughout the course of therapy

- Proper priming with skin-lightening agents such as hydroquinone, kojic acid, and/or other non-hydroquinone skin lightening agents. at least 2 to 3 weeks prior to the initiation of laser therapy

- Performing test treatments/test spots to choose the right fluence

- Individualizing the treatment parameters for the patient and indication

- Use of a laser with a “top-hat” beam profile, large spot size, and lower fluences in darker skin types.

- Avoiding stacking and too much overlap while treating

- Cooling the treated area with continuous air cooling (Zimmer)

- Postoperative ice pack application for a few minutes, application of emollients and a steroid ointment for 3 to 5 days (if blistering or crusting are anticipated).

These simple measures can go a long way in achieving good results while lowering the chance of damage to the skin.[1]

Role of Lasers in Melasma

Dermal melanoses such as nevus of Ota and nevus of Ito have a predictable response to Q-switched Nd:YAG lasers with well-established protocols[10] [Figure - 1] and [Figure - 2]. This article will focus on melasma. Though melasma can be epidermal, dermal or mixed, it is the dermal component that poses significant challenges to topical or standard therapy. Laser therapy has opened up new possibilities to tackle this condition.

|

| Figure 1: Nevus of Ota on the left cheek |

|

| Figure 2: Nevus of Ota after eight Q-switched Nd:YAG laser sessions |

The concept of laser toning has gained popularity in Southeast Asia. This involves a low-fluence, multi-pass technique and multiple sessions at weekly intervals, and is based on the theory of subcellular selective photothermolysis proposed by Mun et al. in 2011.[11] Looking at ultrastructural changes in the melanosome using transmission electron microscopy, they found that, epidermal melanocytes had fewer dendrites after laser treatment than before and that laser treatment caused selective photothermolysis of Stage IV melanosomes. They concluded that laser toning was an effective method for treating melasma through subcellular-selective photothermolysis.

Traditional laser treatment is based upon the principle of selective photothermolysis which results in the destruction and death of pigment-containing cells.[5] However, in response to cell death, inflammation follows and results in repigmentation and recurrence. In contrast, high peak power, ultrashort pulse duration (5 ns) and a flat-top beam result in the destruction of only melanin in target cells, keeping the cell alive in the case of subcellular selective photothermolysis discussed above.[11] Because the fluence used is very low and there is no cell death, inflammation is kept to a minimum which could lead to less frequent recurrences.[11]

Review of Literature

A number of studies have reported the use of low-fluence Q-switched Nd:YAG laser treatment (laser toning) at weekly intervals for 8–10 sessions with some success.[12] Though it is effective effective, the risk of mottled hypopigmentation following multiple Q-switched Nd:YAG laser sessions at frequent intervals has been reported. Hence, caution needs to be exercised while performing this procedure and the risks should be explained to the patients. In our experience, modified laser toning with low fluence and large spot size of 10 mm with treatments performed once in 2 weeks instead of weekly treatments for 6–8 sessions is better as it decreases the risk of hypopigmentation. The chances of recurrence are very high after discontinuing the procedure with some studies noting figures as high as 81%.[12]

Chan et al. reported a series of patients with facial depigmentation after the use of low fluence Q-switched Nd:YAG laser. They concluded that laser toning with low fluence Q-switched 1064 nm Nd:YAG laser for skin rejuvenation and melasma can be associated with mottled depigmentation.[13]

Laser toning can be combined with triple combination therapy (fixed dose combination cream containing hydroquinone, tretioin and fluocinolone). Jeong et al. studied low-fluence Q-switched Nd:YAG laser for melasma with pre- or posttreatment triple combination cream. Laser treatment after topical triple combination cream was found to be safer and more effective than the posttreatment use of topical agents. Use of the triple combination may therefore be a good priming method prior to low fluence Q-switched laser therapy.[14]

Laser toning can be combined with intense pulse light treatment. Na et al. observed that such combination treatment may provide more rapid clinical resolution in mixed-type melasma with possible long-term clinical benefits when compared to laser toning alone.[15]

A study was conducted to investigate the efficacy and safety of 694-nm fractional Q-switched ruby laser combined with sonophoresis on levorotatory vitamin C for the treatment of 26 chinese melasma patients. Mean melasma area severity index score decreased from 15.51 ± 3.00 before treatment to 10.02 ± 4.39 3 months after the final treatment (P < 0.01). Side effects were minimal.[16]

Tian reported a novel technique using a combination of fractional 2940-nm Er: YAG and 1064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG lasers. They achieved a rapid improvement in two cases of melasma in Chinese type III skin, seen within a month of treatment. Follow-up at 6 months showed sustained results with no complications. Though these results are encouraging, a definite conclusion is not possible with only two cases.[17]

Yue et al. found the fractional mode (Pixel) Q-switched Nd:YAG 1064-nm laser an effective and safe treatment for melasma. What was interesting was that they noted that the recurrence rate was lower than with large-spot low-fluence QS Nd:YAG laser. Mean melasma area severity index scores decreased from 12.84 ± 6.89 to 7.29 ± 4.15 after treatment (P = 0.000). Seventy percent of the patients got moderate-to-good improvements after all the treatments (8 sessions). They reported partial recurrence in 40% of the patients at the 3-month follow-up.[9]

Long-term recurrence rates may be high after low-fluence 1064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser treatment in melasma. Gokalp et al. evaluated 34 melasma patients using a 1064-nm Q-switched-Nd:YAG laser. The parameters used were 6 mm spot size and 2.5 J/cm2 fluence with multiple passes for 6–10 (median 8) sessions at 2-week intervals. After the low-fluence 1064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser treatments, the mean modified melasma area severity index score decreased from 6.7 ± 3.3 to 3.2 ± 1.6 (P < 0.01). After treatment completion, 58.8% of the patients rated themselves as having at least a 50% reduction in melasma severity. One year after the last treatment, recurrence was observed in 20 patients (58.8%) and the mean modified melasma area severity index score had increased from 3.2 ± 1.6 to 5.8 ± 1.9 in all patients. This was one of the few studies where the follow-up duration was fairly long (1 year).[18]

A study by Kim et al. was done to investigate the efficacy and adverse effects after repeated low-fluence 1064 nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser treatment with photoacoustic twin pulse mode in Asian women with melasma.[19] They found that after 5 sessions of laser therapy, approximately 60% of the patients showed significant improvement. It was concluded that a few sessions of repeated laser toning treatment using the photoacoustic twin pulse mode is a safe and effective way to treat facial melasma. Photoacoustic twin pulse involves splitting of the laser pulse into two with an interval of 100 microseconds between the two pulses. The energy is thus halved rather than a single high peak energy pulse. This mode is recommended for patients with sensitive skin or a low pain threshold.

Twenty patients were treated with 10 weekly sessions of low-fluence 1064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser at 1-week intervals by Hofbauer Parra et al.[11] They used a modified melasma area severity index for evaluation up to 6 months after the last session. Epidermal melanin quantification was performed on 10 biopsy samples and compared before and after treatment. All patients showed improvement by modified melasma area severity index scores, ranging from 21% to 75% from baseline. No permanent adverse effects were found but the recurrence rate was 81%. These results confirm the safety and effectiveness of low-fluence Q-switched Nd:YAG laser for treating melasma, but the high recurrence rate suggests poor long-term results when the laser is used as a monotherapy.

An update and expert opinion on melasma and post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation published by Sofen et al. opined that combining topical therapy with procedures such as peels, intense pulsed light, fractional nonablative lasers or radiofrequency, pigment lasers (microsecond, picosecond, Q-switched) and microneedling enhanced the results in management of melasma.[20] Their conclusion was that with proper treatment, melasma can be controlled, improved and maintained.

Mottled hypopigmentation has been frequently reported as a complication of laser toning. Jang et al. found that laser toning-induced hypopigmentation was characterized by almost-destroyed melanosome pigments and a preserved number of melanocytes, which seem to be functionally downregulated not to produce fully-matured melanosomes.[21] The presence of such downregulated melanocytes might allow some degree of recovery. Early discontinuation of laser toning, use of tacrolimus ointment and excimer light targeted phototherapy may therefore help in this situation.

Most of the data available on low-fluence laser toning is for Q-switched Nd:YAG laser. Fabi et al. compared low-fluence Q-switched Nd:YAG laser with low fluence Q-switched Alexandrite 755 nm laser.[22] They observed that both modalities were equally effective at improving moderate-to-severe mixed-type facial melasma.

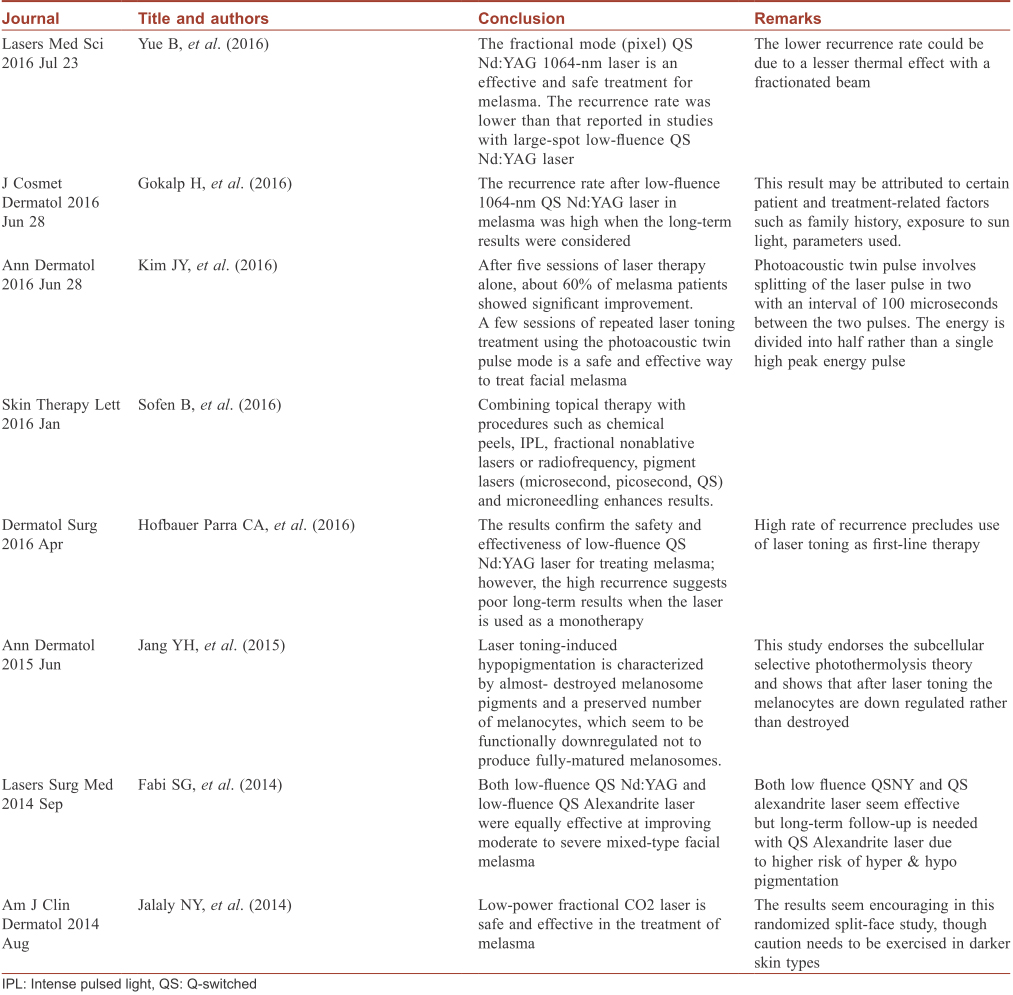

Low-power fractional CO2 laser too may be considered in the treatment of melasma. Jalaly et al. compared low-powered fractional CO2 laser with low-fluence Q-switched Nd:YAG laser in melasma in a randomized, controlled split-face study.[23] The differences between the mean melanin index and modified melasma area severity index scores at baseline and 2-month follow-up were compared between the two treatments. It was seen that the reduction of scores was significantly more on the fractional CO2 laser-treated side than on the Q-switched 1064 nm Nd:YAG laser-treated side (P < 0.001). A summary of the recent evidence on laser therapy of melasma is shown in the [Table - 1].

In the author's experience, laser toning with a Q-switched 1064 nm Nd:YAG laser with a 10 mm spot size at 1.2 J/cm2, and a 10 Hz repetition rate with a multipass technique to an end-point of erythema without frosting, done once in 2 weeks for 6–10 sessions works best. In patients with sensitive skin, the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser pulse can be split into two (in select models) with a 100-microsecond interval between the two pulses, thereby lowering the discomfort or pain. This is called photoacoustic twin pulse or quick pulse-to-pulse mode in specific laser systems. For instance if a fluence of 1200 mJ is to be used, then by using a split-pulse two quick pulses of 600 mJ with an interval of 100 microseconds are delivered. The use of air cooling with the Zimmer cooling system also aids in minimizing patient discomfort.

Acquired Dermal Melanoses

Riehl's melanosis characterized by diffuse gray-to-black hyperpigmentation around the face is a challenge to treat. Kwon et al. in a pilot study using a triple combination approach (low fluence Q-switched Nd:YAG laser, hydroquinone cream and oral tranexamic acid) for the treatment of Riehl's melanosis in 8 patients found significant improvement after 10–18 sessions.[24]

Lichen planus pigmentosus is characterized by bluish-gray macular hyperpigmentation that is often distributed on the face, neck, upper trunk and arms. Histological features include an interface dermatitis, pigment incontinence and dermal melanophages. The pigmentation can be persistent and recalcitrant to medical therapy. Once disease activity ceases, the residual pigmentation can be tackled by a Q-switched Nd:YAG laser. In the author's experience, multiple (around 5) sessions of Q-switched Nd:YAG at 4–6 week intervals using a large spot size and moderate fluences (which vary with the laser used) yield excellent results. In a series of 10 patients (unpublished data), very good clearing was observed using this protocol, as seen in [Figure - 3], [Figure - 4], [Figure - 5], [Figure - 6], [Figure - 7], [Figure - 8]. The parameters used in (lichen planus pigmentosus) with the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser were 1064 nm wavelength, 8 mm spot size, 1.5–1.8 J/cm2 fluence and a 5–10 Hz repetition rate.

|

| Figure 3: Lichen planus pigmentosus before laser therapy |

|

| Figure 4: Lichen planus pigmentosus after five sessions with the Q-switched Nd:YAG laser |

|

| Figure 5: Lichen planus pigmentosus before laser therapy |

|

| Figure 6: Lichen planus pigmentosus after five Q-switched Nd:YAG laser treatments at 1-month intervals |

|

| Figure 7: Lichen planus pigmentosus on the temple area |

|

| Figure 8: Lichen planus pigmentosus after five sessions of Q-switched Nd:YAG laser |

Hori's nevus or acquired bilateral nevus of Ota-like macules is another condition that responds well to Q-switched Nd:YAG treatment[1],[7]. It is differentiated from nevus of Ota by later onset, lack of scleral involvement and its bilateral nature. Around five sessions are needed at 4–6 week intervals with the 1064 nm wavelength, 5 mm spot size, fluence of 4–5 J/cm,2 [Figure - 9] and [Figure - 10]. Recurrences are uncommon[7].

|

| Figure 9: Hori's nevus |

|

| Figure 10: Hori's nevus after five Q-switched Nd:YAG laser sessions |

Key points

- Lasers can be used in selected resistant cases of melasma when medical therapy fails or the patient is intolerant to topical medication For melasma, most evidence available is for laser toning (low fluence, multi-pass Q-switched Nd:YAG laser technique).

- Nevus of Ota and Hori's nevus respond well to Q-switched Nd:YAG laser. Recurrences are very rare upon clearing of the lesion

- Lichen planus pigmentosus should be treated only when the condition has stabilized and there is no spread of the disease. Laser can be used in selected cases when activity ceases, and Q-switched Nd:YAG at 1064 nm can help clear the residual hyperpigmentation. However, multiple sittings are necessary.

Conclusion

Significant strides have been made in laser technology aiding in the successful management of dermal melanoses and melasma. Though a large number of studies have been done on melasma with various lasers including Q-switched Nd:YAG, Q-switched alexandrite lasers, ablative fractional lasers, intense pulse light, and non ablative fractional lasers there is no clear consensus on the correct protocol or combination. Most of these studies have shown encouraging results in melasma and other dermal conditions. Though results are good, recurrence rates reported have been particularly high for melasma, precluding the use of lasers as first line or even second line therapy. They are used at best as a last option in recalcitrant melasma or those intolerant to other modalities. Conditions such as Hori's nevus, Riehl's melanosis and lichen planus pigmentosus do show a good response to laser therapy and further studies will help establish the role of lasers in these dermal melanoses.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Aurangabadkar S, Mysore V. Standard guidelines of care: Lasers for tattoos and pigmented lesions. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2009;75 Suppl 2:111-26.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Kilmer SL, Wheeland RG, Goldberg DJ, Anderson RR. Treatment of epidermal pigmented lesions with the frequency-doubled Q-switched Nd:YAG laser. A controlled, single-impact, dose-response, multicenter trial. Arch Dermatol 1994;130:1515-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Goldberg DJ. Pigmented lesions, tattoos, and disorders of hypopigmentation. In: Goldberg DJ, editor. Laser Dermatology Pearls and Problems. 1st ed. Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing; 2008. p. 71-114.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Kilmer SL, Garden JM. Laser treatment of pigmented lesions and tattoos. Semin Cutan Med Surg 2000;19:232-44.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Anderson RR, Parrish JA. Selective photothermolysis: Precise microsurgery by selective absorption of pulsed radiation. Science 1983;220:524-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Barlow RJ, Hruza GJ. Lasers and light tissue interactions. In: Goldberg DJ, Dover JS, Alam M, editors. Procedures in Cosmetic Dermatology: Laser and Lights. 1st ed., Vol. 1. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005. p. 1-11.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Polla LL, Margolis RJ, Dover JS, Whitaker D, Murphy GF, Jacques SL, et al. Melanosomes are a primary target of Q-switched ruby laser irradiation in guinea pig skin. J Invest Dermatol 1987;89:281-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Anderson RR, Margolis RJ, Watenabe S, Flotte T, Hruza GJ, Dover JS, et al. Selective photothermolysis of cutaneous pigmentation by Q-switched Nd:YAG laser pulses at 1064, 532, and 355 nm. J Invest Dermatol 1989;93:28-32.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Yue B, Yang Q, Xu J, Lu Z. Efficacy and safety of fractional Q-switched 1064-nm neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser in the treatment of melasma in Chinese patients. Lasers Med Sci 2016;31:1657-63.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Aurangabadkar S. QYAG5 Q-switched Nd:YAG laser treatment of nevus of ota: An Indian study of 50 patients. J Cutan Aesthet Surg 2008;1:80-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Mun JY, Jeong SY, Kim JH, Han SS, Kim IH. A low fluence Q-switched Nd:YAG laser modifies the 3D structure of melanocyte and ultrastructure of melanosome by subcellular-selective photothermolysis. J Electron Microsc (Tokyo) 2011;60:11-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Hofbauer Parra CA, Careta MF, Valente NY, de Sanches Osório NE, Torezan LA. Clinical and histopathologic assessment of facial melasma after low-fluence Q-switched neodymium-doped yttrium aluminium garnet laser. Dermatol Surg 2016;42:507-12.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Chan NP, Ho SG, Shek SY, Yeung CK, Chan HH. A case series of facial depigmentation associated with low fluence Q-switched 1,064 nm Nd:YAG laser for skin rejuvenation and melasma. Lasers Surg Med 2010;42:712-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Jeong SY, Shin JB, Yeo UC, Kim WS, Kim IH. Low-fluence Q-switched neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet laser for melasma with pre- or post-treatment triple combination cream. Dermatol Surg 2010;36:909-18.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Na SY, Cho S, Lee JH. Combinational treatment using intense pulsed light and low fluence Q-switched Nd:YAG laser over laser treatment alone. Lasers Surg Med 2010;42:712-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Zhou HL, Hu B, Zhang C. Efficacy of 694-nm fractional Q-switched ruby laser (QSRL) combined with sonophoresis on levorotatory vitamin C for treatment of melasma in Chinese patients. Lasers Med Sci 2016;31:991-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Tian WC. Novel technique to treat melasma in Chinese: The combination of 2940-nm fractional Er: YAG and 1064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser. J Cosmet Laser Ther 2016;18:72-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Gokalp H, Akkaya AD, Oram Y. Long-term results in low-fluence 1064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser for melasma: Is it effective? J Cosmet Dermatol 2016;15:420-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Kim JY, Choi M, Nam CH, Kim JS, Kim MH, Park BC, et al. Treatment of melasma with the photoacoustic twin pulse mode of low-fluence 1,064 nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser. Ann Dermatol 2016;28:290-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Sofen B, Prado G, Emer J. Melasma and post inflammatory hyperpigmentation: Management update and expert opinion. Skin Therapy Lett 2016;21:1-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Jang YH, Park JY, Park YJ, Kang HY. Changes in melanin and melanocytes in mottled hypopigmentation after low-fluence 1,064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser treatment for melasma. Ann Dermatol 2015;27:340-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Fabi SG, Friedmann DP, Niwa Massaki AB, Goldman MP. A randomized, split-face clinical trial of low-fluence Q-switched neodymium-doped yttrium aluminum garnet (1,064 nm) laser versus low-fluence Q-switched alexandrite laser (755 nm) for the treatment of facial melasma. Lasers Surg Med 2014;46:531-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Jalaly NY, Valizadeh N, Barikbin B, Yousefi M. Low-power fractional CO2 laser versus low-fluence Q-switch 1,064 nm Nd:YAG laser for treatment of melasma: A randomized, controlled, split-face study. Am J Clin Dermatol 2014;15:357-63.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Kwon HH, Ohn J, Suh DH, Park HY, Choi SC, Jung JY, et al. Apilot study for triple combination therapy with a low-fluence 1064 nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser, hydroquinone cream and oral tranexamic acid for recalcitrant Riehl's melanosis. J Dermatolog Treat 2017;28:155-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

36,807

PDF downloads

5,986