Translate this page into:

Oral isotretinoin in different dose regimens for acne vulgaris: A randomized comparative trial

Correspondence Address:

Uma Shankar Agarwal

397, Shankar Niwas, Sri Gopal Nagar, Gujjar ki Thadi, Jaipur - 302 019

India

| How to cite this article: Agarwal US, Besarwal RK, Bhola K. Oral isotretinoin in different dose regimens for acne vulgaris: A randomized comparative trial. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2011;77:688-694 |

Abstract

Background: Oral isotretinoin is recommended for severe nodulocystic acne in the doses of 1-2 mg/kg/day which is usually associated with higher incidence of adverse effects. To reduce the incidence of side-effects and to make it more cost-effective, the lower dose regimen of isotretinoin has been used. Aim: To compare the efficacy and tolerability of oral isotretinoin in daily, alternate, pulse and low-dose regimens in acne of all types and also to assess whether it can be used for mild and moderate acne also. Methods: One hundred and twenty patients with acne were randomized into four different treatment regimens each consisting of 30 patients. Group A was prescribed isotretinoin 1 mg/kg/day, Group B 1 mg/kg alternate day, Group C 1 mg/kg/day for one week/four weeks and Group D 20 mg every alternate day for 16 weeks. Patients were further followed for eight weeks to see any relapse. Side-effects were also recorded. Results: Though the daily high dose treatment Group A performed better initially at eight weeks, at the end of therapy at 16 weeks results were comparable in Group A , B and D. Patients with severe acne did better in Group A than in Group B, C and D. Patients with mild acne had almost similar results in all the groups while patients with moderate acne did better in Group A, B and D. Frequency and severity of treatment-related side-effects were significantly higher in treatment Group A as compared to Group B, C and D. Conclusion: We conclude that for severe acne either conventional high doses of isotretinoin may be used or we can give conventional high dose for initial eight weeks and later maintain on low doses. Use of isotretinoin should be considered in mild to moderate acne also, in low doses; 20 mg, alternate day seems to be an effective and safe treatment option in such cases.Introduction

Acne vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory disease of pilosebaceous units, characterized by comedones, papules, pustules, nodules, cysts, abscesses and later on sometimes as widespread scarring. [1] Acne is distributed mainly over the face, upper back, chest and upper arms. This disease occurs worldwide and usually starts in adolescence and resolves by the mid-twenties. [2] According to the severity of acne, there are various treatment modalities. They include both topical and systemic therapy. In systemic therapy the commonly used drugs are oral antibiotics and oral isotretinoin. Isotretinoin (13-cis retinoic acid) represents the single most important advance in acne therapeutics. [3] Isotretinoin is given in a dosage of 0.5 to 1.0 mg/kg/day after meals in severe nodulocystic acne and the treatment is continued till a cumulative dose of 120-150 mg/kg has been achieved. This causes many dose-dependent mucocutaneous and systemic side-effects. To overcome this limitation lower doses of isotretinoin are being tried. Lower doses of isotretinoin may be effective in terms of side-effects and cost, therefore, other regimens may be used instead of daily conventional dose. [4] To compare the efficacy and tolerability of various therapeutic regimens (daily, alternate, pulse and low dose) of oral isotretinoin in acne vulgaris, the present prospective study was undertaken.

Methods

This prospective study of the comparative efficacy and tolerability of various therapeutic regimens (daily, alternate, pulse and low dose) of oral isotretinoin in acne vulgaris was carried out in the department of Skin, STD and Leprosy in SMS Medical College and Hospital, Jaipur. A total number of 120 patients with acne were included in the study. Pregnant females, married females desiring to get pregnant or using temporary methods of contraception, patients having family and/or personal history of hyperlipidemia or diabetes and those having drug-induced acne were excluded. All patients were included after written informed consent. After recording detailed demographic data (which included age, sex, age of onset of disease, duration of disease etc.), the patients were examined under good illumination and were finally graded into mild, moderate and severe on the basis of severity as described below (Pochi et al[5] ).

- Mild disease: Few to several papules/pustules with no nodule

- Moderate disease: Several to many papules/pustules with few to several nodules

- Severe disease: Numerous and/or extensive papules/pustules with many nodules

Total acne load was calculated on the basis of Definition Severity Index [6] which was calculated as follows:

- Non-inflamed comedones, open and closed (no erythema) - 0.5

- Comedones/papules with surrounding erythema - 1

- Superficial pustules < 2 mm with no or little erythema - 1

- Pustules with a diameter > 2 mm - 2

- Pustules with a significant erythema - 2

- Deep infiltrates with or without pustules/ nodules/ isolated cysts - 3

Total acne load can be calculated by multiplying the total number of each type of lesion with its severity index and adding them all together.

Complete blood cell counts, liver function tests (LFTs) and serum lipid profile were carried out initially and repeated at four-weekly intervals for 16 weeks. The criterion for discontinuation of therapy was a blood test rising above the following values in the first two months of follow-up: triglycerides > 400 mg/dL (4.52 mmol/L), alkaline phosphatase > 264/UL (female), > 500/UL (male), ALT (Alanine transaminase) > 62/UL, AST (Aspartate aminotransferase) > 80/UL, cholesterol > 300 mg/dL (> 7.7 mmol/L).

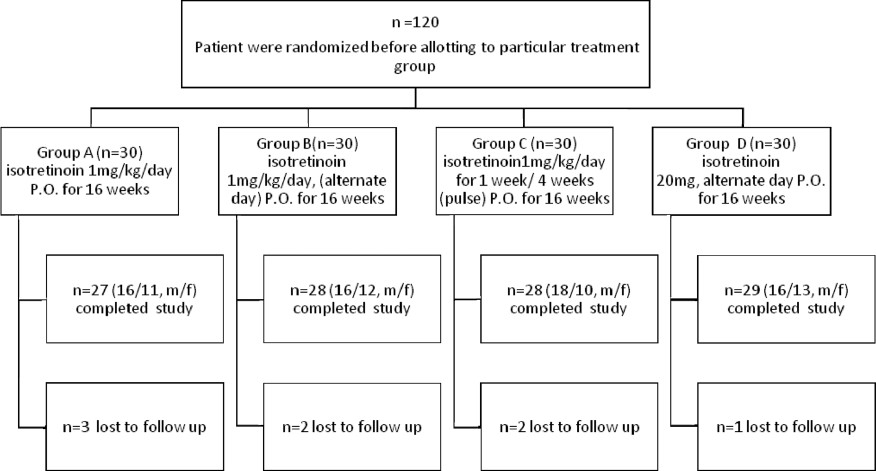

Patients were randomized by stratified randomization method into four different treatment regimens each consisting of 30 patients [Figure - 1]. Group A was prescribed isotretinoin 1 mg/kg/day, Group B was prescribed 1 mg/kg alternate day, Group C was prescribed 1 mg/kg/day for one week/four weeks and Group D was prescribed a fixed low-dose regimen of 20 mg every alternate day for 16 weeks. Along with oral isotretinoin, all patients were also given oral azithromycin 500 mg once a day 1 h before meals for three days a week for three weeks. All the patients were also advised to apply topical 1% clindamycin phosphate cream twice daily. Patients were followed up at two-weekly intervals for 24 weeks. Improvements in lesions were recorded by measuring total acne load at each visit. Side-effects were recorded at each visit which included incidence and severity of cheilitis, dry skin, mouth, nose and eyes, epistaxis, facial redness, rashes, hair loss, photosensitivity, nail changes and systemic side-effects like fatigue, bone/ joint pains, muscular cramps etc. A failure of treatment was defined as no improvement, requiring subsequent increase in isotretinoin dosage or even additional treatment at the end of 16 weeks of treatment. Emergence of near pretreatment severity of acne in the treated patient within eight weeks of follow-up was considered as relapse. All the findings were analyzed by Chi square, ANOVA (Analysis of variance), repeated ANOVA and Wilcoxon statistical test wherever required.

|

| Figure 1: Flowchart of patients participating in the study |

The study protocol was approved by the research review board of SMS Medical College and had no financial support from any agency.

Results

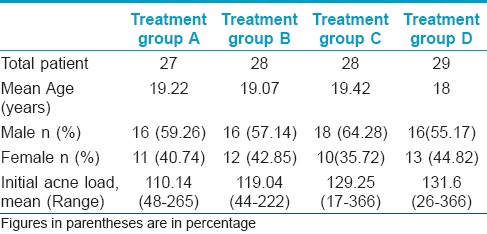

A total of 120 patients with a mean age of 18.95 years (range 14-26, median 19) were included in the present prospective study. The demographic data of all the patients in different groups including age, sex, initial mean acne load (score) and acne severity is mentioned in [Table - 1] and [Table - 2], respectively. No statistically significant difference was noted in different groups as far as age and sex were considered [age (P =0.46) and sex (P = 0.8)]. For final result analysis there were 112 patients as described in the flowchart [Figure - 1].

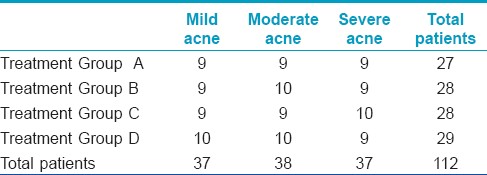

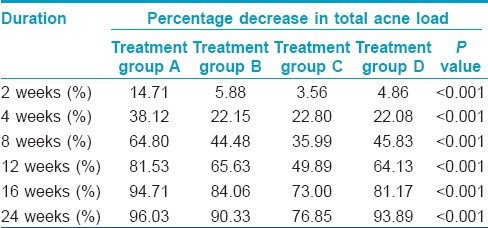

The initial mean acne scores were 110.14 (range 48-265) in Group A, 119.04 (range 44-222) in Group B, 129.25 (range 17-366) in Group C and 131.6 (range 26-366) in Group D [Table - 1]. It was statistically comparable in all treatment groups as per Mann Whitney tests for independent samples (P value <0.5 in each group compared). During follow-up it was found that there was a statistically significant decrease in total acne load in all groups as per Wilcoxon paired two-tailed probability [Figure - 2], [Table - 3] and [Table - 4].

|

| Figure 2: Total acne load during follow-up in different groups |

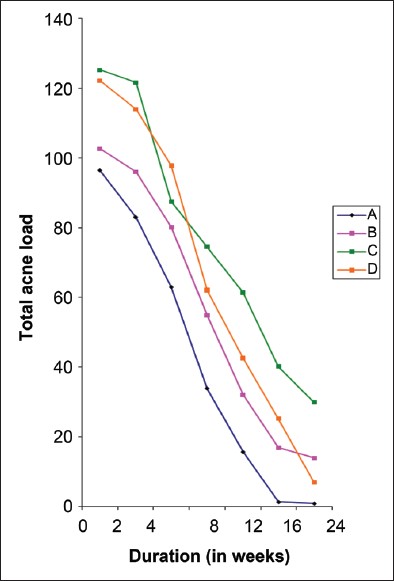

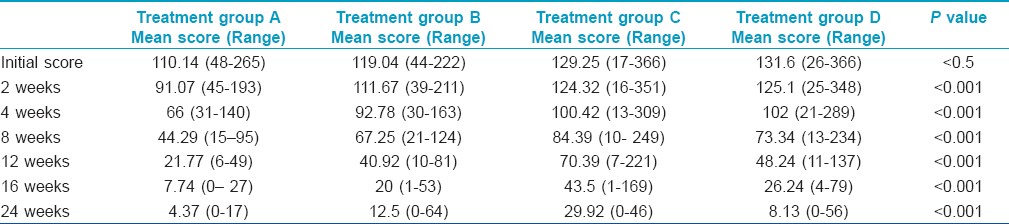

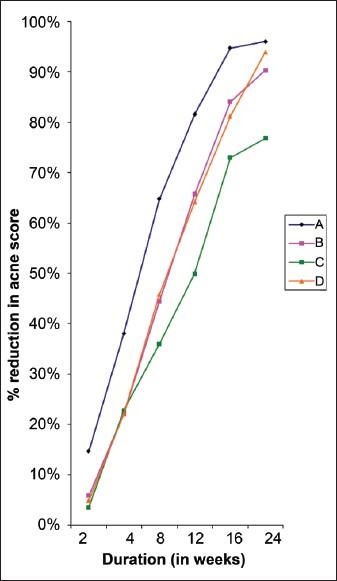

Response rates in the different groups are summarized in [Table - 3] and depicted in [Figure - 3]. On application of repeated measurement of ANOVA, it was observed that there was a statistically significant difference in response rate between different treatment groups. The earliest response was noted in Group A (P value <0.001). But after eight weeks of therapy all treatment groups started showing significant improvement and at the end of therapy (16 weeks) results in Groups A, B and D were comparable while Group C performed the worst.

|

| Figure 3: Response rate (percentage decrease in acne score) of various treatment protocols with respect to duration |

When the results were evaluated while considering the disease severity i.e. mild, moderate and severe [Figure - 4], a statistically significant difference in response rate was noted (P value = 0.02). Patients with severe disease did better in Group A as compared to groups B, C and D. Patients with mild disease did equally well in all treatment groups whereas patients with moderate disease did better in all groups except for Group C at the end of treatment.

|

| Figure 4: Comparison of treatment response with severity of disease in different groups |

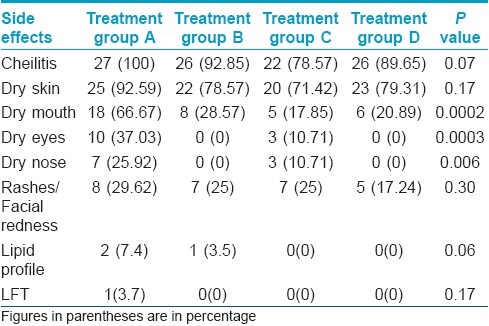

Mucocutaneous side-effects (cheilitis, dry skin, dry mouth, dry nose, dry eyes, etc.) appeared earlier in Group A at two weeks and gradually increased in severity, while they appeared after four to six weeks in other groups. The most common side-effects were cheilitis and dry skin [Table - 5]. Facial redness/rashes were the most common side-effects in treatment Group A (29.6%). Lipids were raised in treatment Group A and B only. Liver function tests were deranged in only treatment Group A (3.7%). Other side-effects of isotretinoin like epistaxis, fatigue, hair loss, bone/ joint pains, muscular cramps etc. were not seen in any treatment groups. There were no pregnancies and none of the patients developed depression or other psychological side-effects. Thus the incidence of side-effects was the highest in Group A and minimum in Group D. The severity of side-effects was also more in Group A. All the side-effects were successfully managed and no patient required discontinuation of therapy.

In our study no patient relapsed at the end of 24 weeks i.e. reached the pre-treatment severity score.

Discussion

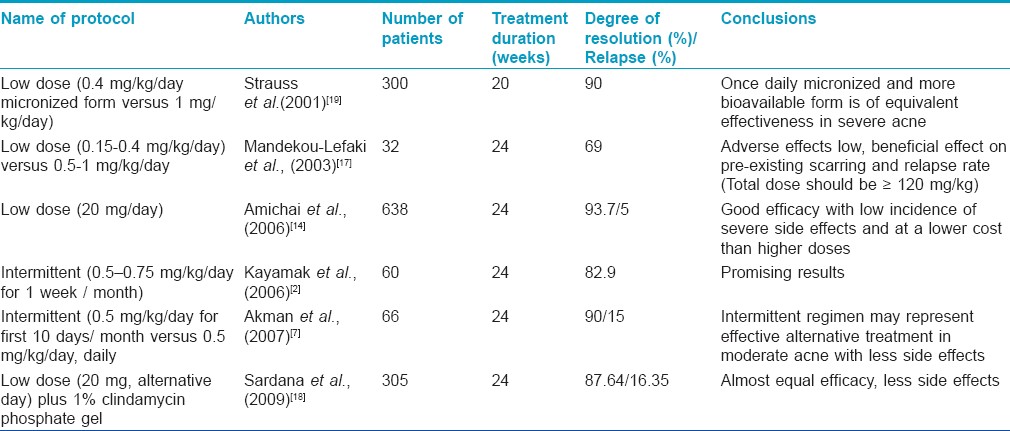

Isotretinoin is quite a useful therapeutic advance in the management of acne. It has been recommended for the treatment of severe nodulocystic acne in the doses of 1-2 mg/day. [7],[8],[9],[10] While using this treatment protocol the incidence of side-effects is quite high and requires regular monitoring including a watch on the serum lipid profile. It has been debated whether isotretinoin should be reserved for severe nodulocystic acne only or it can be used for mild and moderate acne also. [11] To decrease the incidence of side-effects and to make the therapy protocol simpler, the lower dose regimen has been tried by various authors. [12],[13],[14],[15],[16] Different studies using low-dose and intermittent regimens of isotretinoin have been summarized in [Table - 6]. Most of these studies have found that low-dose and intermittent regimens of isotretinoin are effective in moderate to severe acne with a low incidence and severity of side-effects.

In the present study we have tried to compare four different regimens of oral isotretinoin simultaneously and have also tried to correlate treatment response not only with total acne load but also with severity of the disease. The daily high-dose treatment group (1 mg/kg/day) performed best in terms of response till the eighth week but it was comparable with Group B and Group D but not with Group C which did worst. When the results were compared as per severity of disease (mild, moderate and severe), a significant level of difference was noted among the various treatment groups. Patients with severe acne did better in Group A than in groups B, C and D. However, moderate acne had almost similar results in all the groups except in Group C.

The frequency and severity of treatment-related side-effects like cheilitis, dry skin, dry mouth, dry nose and facial redness were significantly higher in treatment Group A as compared to groups B, C and D. Previous studies had also shown that low-dose isotretinoin has lesser side-effects as compared to conventional high-dose regimens . In treatment Group A, slight elevation of liver enzymes was noted in 3.7% of the patients. Up to 40% increase of serum lipid levels was also noted in treatment Group A (7.4%) and Group B (3.5%). These side-effects were quite lower than other studies with a conventional dose regimen (hyperlipidemia in 20-35% and elevated liver enzymes in approximately 4-10% cases). [19],[20],[21],[22]

In our study, azithromycin was added for the initial three weeks to reduce the Propionibacterium acnes load. It has minimal side-effects, good compliance and resistance has not been reported in acne patients till date. [23],[24] Though it might have had an additive effect in reducing the acne load it was used in all groups for equal duration.

Comparing the treatment efficacy and side-effects of various treatment regimens, we found that low-dose isotretinoin is almost equal in efficacy to daily high-dose regimen but with the advantage of less side-effects and more cost-effectiveness. For severe acne either the conventional high dose may be used or we can give the conventional high dose for the initial eight weeks and later maintain on low doses. Considering the above findings, the use of isotretinoin should be considered in mild to moderate acne also, in low doses; 20 mg, alternate day seems to be an effective and safe treatment option in such cases. One can argue that the relapse rate is lower with the conventional high-dose regimen than lower doses, which was not observed in our study. It may be because of the short duration of follow-up of eight weeks.

| 1. |

Dreno B, Poli F. Epidemiology of acne. Dermatology 2003;43:1042-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Kaymak Y, Ilter N. The effectiveness of intermittent isotretinoin treatment in mild or moderate acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006;20:1256-60.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Harper JC, Thibutot DM. Pathogenesis of acne: Recent research advances. Adv Dermatol 2003;19:1-10.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Cunliffe W, Gollnick H. Acne. In: Arndt KA, LeBoit PE, Robinson JK, Wintroub BU, editors. Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders Co; 1996. p. 461-80.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Pochi PE, Shalita AR, Strauss JS, Webster SB, Cunliffe WJ, Katz HI, et al. Report of the consensus conference on acne classification. J Am Acad Dermatol 1991;24:495-500.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Liden S, Goransson K, Odsell L. Clinical evaluation in acne. Acta Dermato Venereol Suppl (Stockh) 1980;89:47-52.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Akman A, Durusoy C, Senturk M, Koc CK, Soyturk D, Alpossy E. Treatment of acne with intermittent and conventional isotretinoin: A randomised controlled multicenter study. Arch Dermatol Res 2007;299:467-73.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Culniffe WJ, van de Kerkhof PC, Caputo R, Cavicchini S, Cooper A, Fyrand OL, et al. Roaccutane treatment guidelines: results of an international survey. Dermatology 1997;194:351-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Peck GL, Olsen TG, Yoder FW, Downing DT, Pandya M, et al. Prolonged remissions of cystic and conglobate acne with 13-cis-retinoic acid. N Engl J Med 1979;300:329-33.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Farrell LN, Strauss JS, Stranieri AM. The treatment of severe cystic acne with 13-cis-retinoic acid. Evaluation of sebum production and the clinical response in a multiple-dose trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 1980;3:602-11.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Bellosta M, Vignini M, Miori L, Rabbiosi G. Low-dose isotretinoin in severe acne. Int J Tissue React 1987;9:443-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Goulden V, Clark SM, Cunliffe WJ. Post adolescent acne: A review of clinical features. Br J Dermatol 1997;136:66-70.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Hermes B, Praetel C, Henz BM. Medium dose isotretinoin for the treatment of acne. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 1998;11:117-21.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Geissler SE, Michelsen S, Plewig G. Very low dose isotretinoin is effective in controlling seborrhoea. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2003;1:952-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Amichai B. Long term mini doses of isotretinoin in the treatment of relapsing acne. J Dermatol 2003;30:572.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Sardana K, Garg VK, Sehgal VN, Mahajan S, Bhushan P. Efficacy of fixed low-dose isotretinoin (20 mg, alternate days) with topical clindamycin gel in moderately severe acne vulgaris. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2009;23:556-60.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Mandekou- Lefaki I, Delli F, Teknetzis A, Euthimiadou R, Karakatsanis G. Low dose schema of isotrinoin in acne vulgaris. Int J Clinical Pharmacol Res 2003;23:41-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Sardana K, Garg VK. Efficacy of low dose of isotretinoin in acne vulgaris. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2010;77:7-13.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Strauss JS, Leyden JJ, Lucky AW, Lookingbill DP, Drake LA, Hanifin JM, et al. A randomized trial of the efficacy of a new micronized formulation versus a standard formulation of isotretinoin in patients with severe recalcitrant nodular acne. J Am Acad Dermatol 2001;45:187-95.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Amichai B, Shemer A, Grunwald MH. Low-dose isotretinoin in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;54:644-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Palmer RA, Sidhu S, Goodwin PG. 'Microdose' isotretinoin. Br J Dermatol 2000;143:205-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Sardana K, Sehgal VN. Retinoids: Fascinating up-and-coming scenario. J Dermatol 2003;30:355-80.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Ross JI, Snelling AM, Carnegie E, Coates P, Cunliffe WJ, Bettoli V, et al. Antibiotic-resistant acne: Lessons from Europe. Br J Dermatol 2003;148:467-78.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Rafiei R, Yaghoobi R. Azithromycin versus tetracycline in the treatment of acne vulgaris. J Dermatolog Treat 2006;17:217-21.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

27,341

PDF downloads

4,636