Translate this page into:

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis: Report of four new cases

2 Department of Pediatrics, Mubarak Al-Kabeer Hospital, Kuwait

3 Department of Pediatrics, Al-Adan Hospital, Kuwait

4 Al-Bahar Eye Center, Kuwait

Correspondence Address:

Arti Nanda

P.O. Box: 6759, Salmiya 22078

Kuwait

| How to cite this article: Nanda A, Al-Abdulrazzaq HK, Habeeb YK, Zakkiriah M, Alghadhfan F, Al-Noun R, Al-Ajmi H. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis: Report of four new cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2016;82:298-303 |

Abstract

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis is a rare group of syndromes characterized by the co-existence of a vascular nevus and a pigmentary nevus with or without extracutaneous systemic involvement. The existing classifications of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis are based on phenotypic characteristics. We report four new cases of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis, three with phacomatosis cesioflammea demonstrating phenotypic variability, and one with phacomatosis cesiomarmorata. Extracutaneous manifestations were observed in three patients (75%) that included central nervous system involvement in three, bilateral congenital glaucoma in two, and cardiovascular system involvement in one. The molecular basis of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis is yet to be elucidated. Whether the various subtypes of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis are separate molecular entities or phenotypic variants of the same disease needs to be settled.Introduction

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis is characterized by an association of a vascular nevus with an extensive pigmentary nevus. The first published case dates back to 1910 but the condition was elucidated first by Ota et al. in 1947.[1],[2] In 1985, Hasegawa and Yasuhara classified it into four types based on the pigmentary nevus component, each type further subclassified as (a) having only cutaneous signs or (b) with extracutaneous manifestations.[1] A fifth type was added to this classification later.[3],[4] In order to simplify matters, Happle in 2005 reclassified phacomatosis pigmentovascularis into three major types: (1) phacomatosis cesioflammea, (2) phacomatosis spilorosea and (3) phacomatosis cesiomarmorata [Table - 1].[5] There have been mostly isolated case reports with only a few series describing larger cohorts of patients.[6],[7],[8] A 2008 review included 222 cases and to date, around 250 cases have been reported.[8] Most (75%) patients represent phacomatosis cesioflammea.[6],[7],[8] We report four new cases of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis based on the existing classification scheme.

Case Reports

Case 1

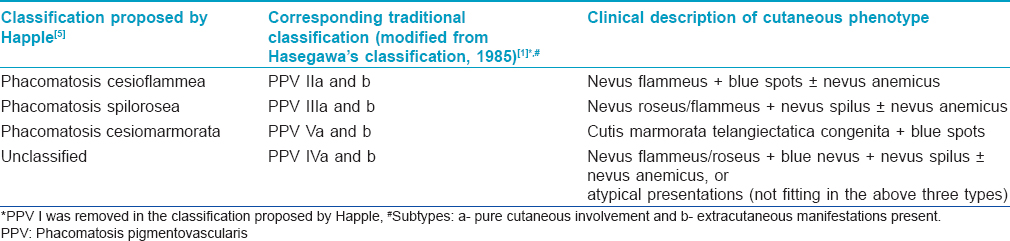

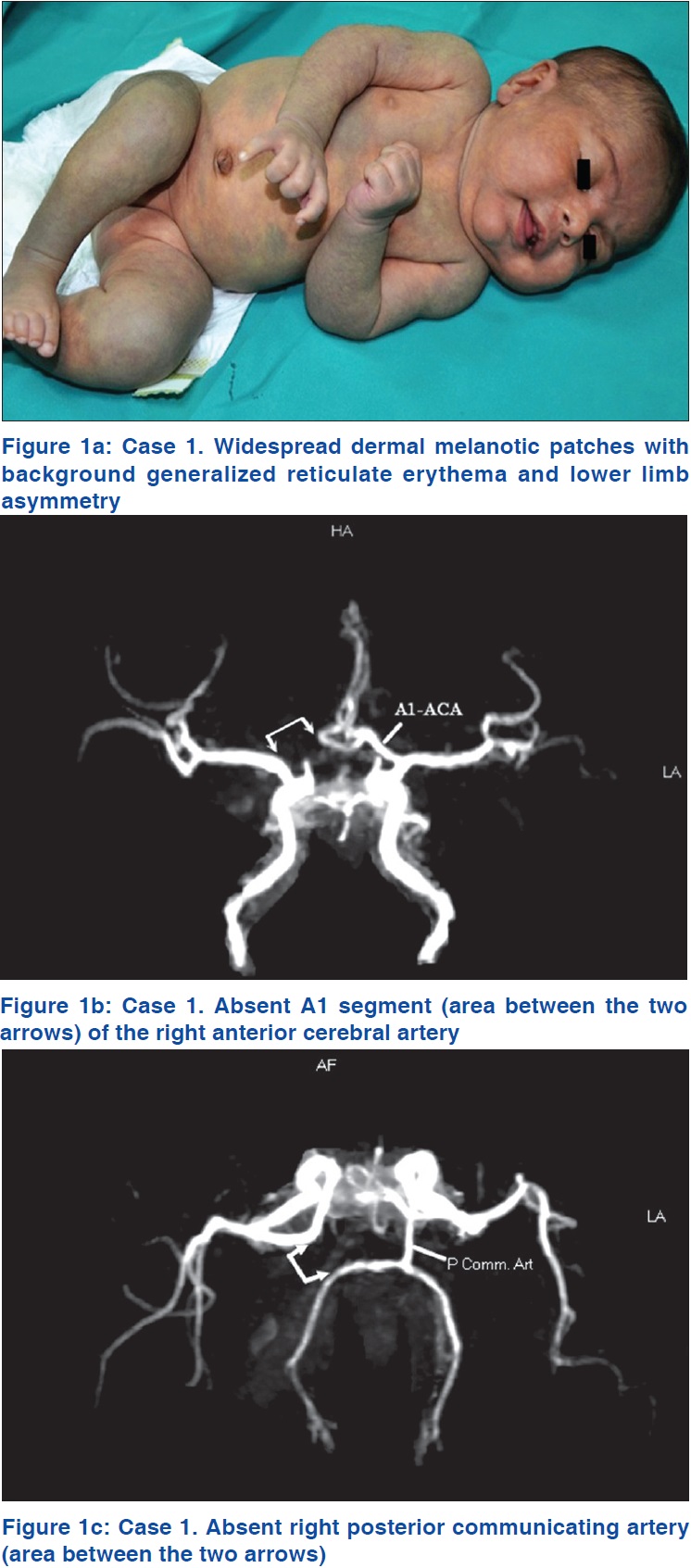

An infant [Table - 2], Patient 2] born to non-consanguineous parents was referred to As'ad Al-Hamad Dermatology Center, Kuwait with widespread bluish spots on a background of mesh-like erythema noticed at birth. She was diagnosed to have bilateral congenital glaucoma soon after birth for which bilateral trabeculotomy and trabeculectomy with intraoperative application of mitomycin C were performed. She showed a good response to these procedures and was under follow-up with a pediatric ophthalmologist. On examination, her height, weight and head circumference were at the 25th percentile. She was observed to have widespread bluish-gray patches occupying most of her trunk and extremities with a background of generalized reticulate erythema [Figure - 1]a. She also had two small infantile hemangiomas, one each on the right thumb and little finger. There was a discrepancy in the length and girth of the lower limbs with the right limb being shorter by 2 cm and its girth (both mid-thigh and mid-calf) being 4 cm less than the left lower limb [Figure - 1]a.

|

| Figure 1 |

Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain showed a prominent sylvian fissure, reduced volume of deep white matter and prominent cortical sulci with pseudoschizencephaly (prominent fissure) between the parietal and occipital cortices. Magnetic resonance angiography of the brain revealed that the A1 segment of the right anterior cerebral artery was absent [Figure - 1]b, with the A1 segment of the left anterior cerebral artery supplying A2 segments of both anterior cerebral arteries. The right posterior communicating artery was also absent [Figure - 1]c. Overall, these findings were consistent with mild cortical atrophy and congenital arterial abnormalities. Magnetic resonance angiography and venography of abdominal and lower limb vessels were normal. An echocardiogram showed left atrial isomerism, absent inferior vena cava with hemiazygos continuation to innominate veins, and a mild atrial septal defect. Various other investigations including ultrasonography of the abdomen, complete blood counts, serum biochemistry and urinalysis were normal.

Case 2

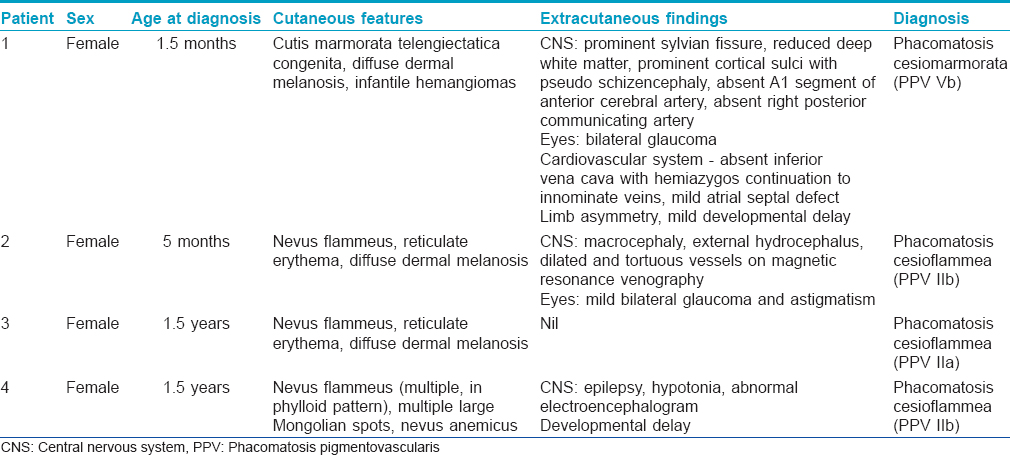

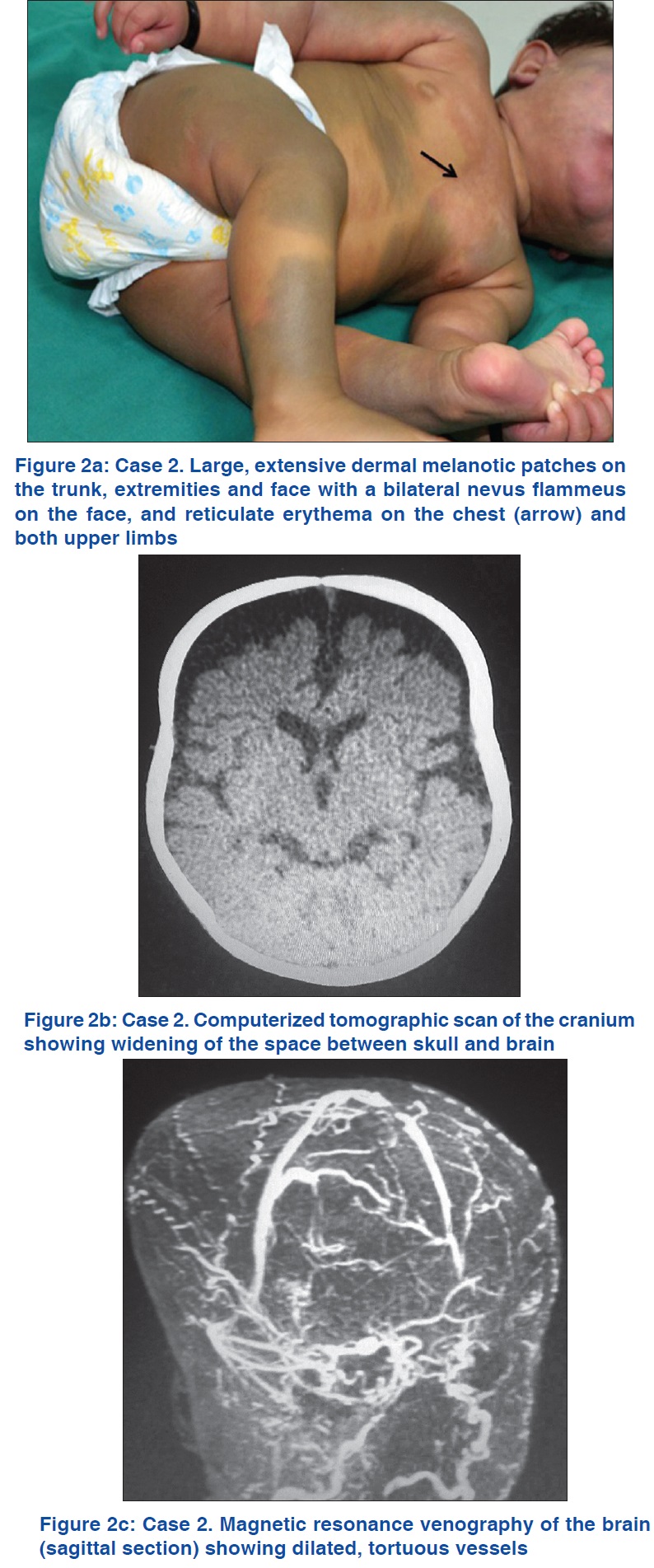

This patient [[Table - 2], Patient 2] was referred to us for evaluation of a widespread vascular nevus and a blue nevus. The firstborn of non-consanguineous parents, she was delivered at term by elective Cesarean section due to brow presentation and prolonged labor. The birth weight was 3.2 kg and she was noticed to have macrocephaly with bilateral eyelid edema soon after birth. On examination, her height and weight were at the 50th percentile and head circumference at the 95th percentile. She was observed to have a nevus flammeus occupying most of her face and diffuse reticulate erythema affecting the chest, shoulders and upper and lower extremities bilaterally [Figure - 2]a. She also had multiple large, widespread, bluish-gray patches on the trunk, extremities and face [Figure - 2]a.

|

| Figure 2 |

Both computerized tomographic scan and magnetic resonance imaging with contrast revealed widening of the space between skull and brain [Figure - 2]b. There was no calcification or evidence of brain atrophy. Magnetic resonance angiography was reported as normal. Magnetic resonance venography showed many tortuous dilated vessels [Figure - 2]c. Eye examination showed mild bilateral glaucoma and astigmatism. The routine laboratory work-up and ultrasonography of the abdomen were found to be normal.

Case 3

A child [[Table - 2], Patient 3] presented to us with a vascular nevus admixed with a pigmented nevus, present since birth. There were no associated medical complaints. Her parents were not consanguineous and her developmental milestones had been normal.

On examination, her height, weight and head circumference were appropriate for her age. She was observed to have a large nevus flammeus affecting the right side of her face and right ear and diffuse reticulate erythema on her neck, upper trunk and extremities. There was also diffuse background dermal melanosis on the upper back, shoulders and upper arms. The routine laboratory tests, ultrasound abdomen, echocardiogram, magnetic resonance imaging and angiography of brain, as well as eye examination were normal.

Case 4

This patient [Table - 2], Patient 4] was referred to us with multiple erythematous macules on the lower limbs, noted at birth. Her birth history was unremarkable and her parents were non-consanguineous. She had recurrent seizures refractory to treatment from 3 days after birth, central hypotonia and developmental delay, starting to sit at age 1 year; at age 1½ years, she was still not standing or walking.

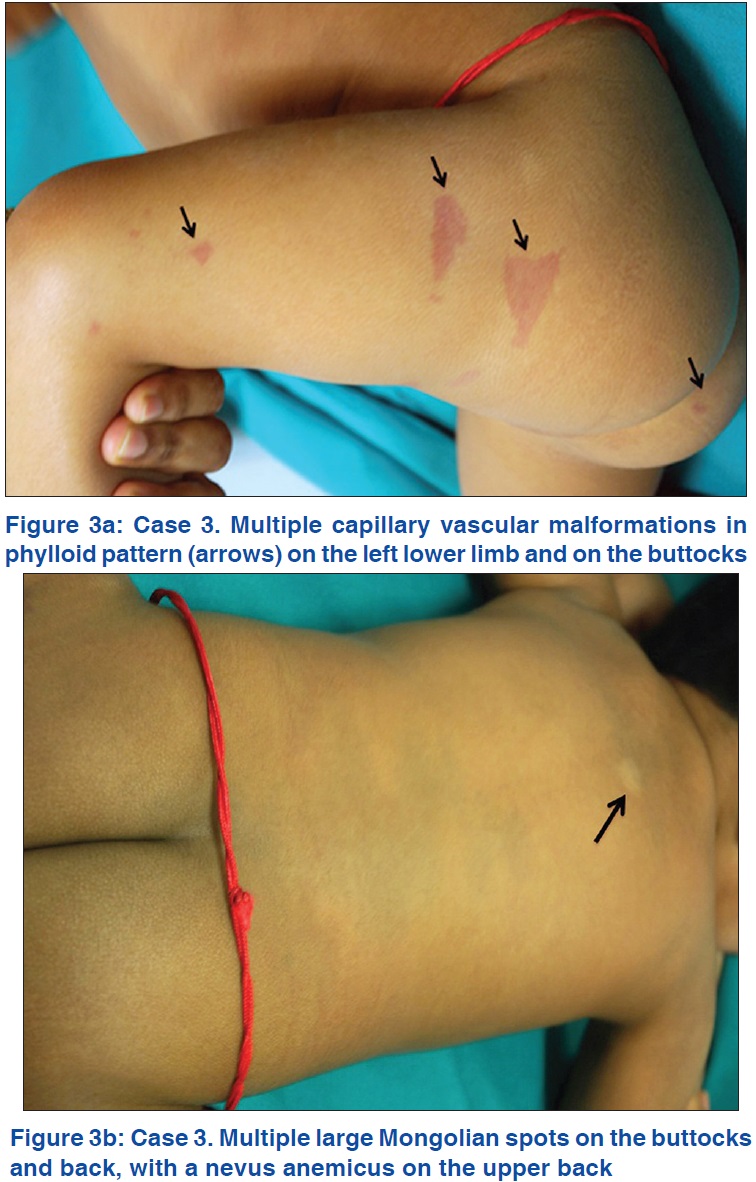

On examination, her height was at the 25th percentile and weight below the 10th percentile. She had mild facial dysmorphism with frontal bossing, hypertelorism and a convergent squint of the left eye. Cutaneous examination revealed multiple erythematous vascular nevi in a phylloid pattern distributed on the left extremity [Figure - 3]a with a few on the right. In addition, she had multiple Mongolian spots on the buttocks, back and shoulders and a nevus anemicus on the upper back [Figure - 3]b. An electroencephalogram showed a markedly abnormal record with slower than normal background activity on both sides. There were high-amplitude sharp and slow waves seen in the temporo-occipital and centro-lateral leads with several short, irregular but high voltage spikes. Magnetic resonance imaging of the brain done twice at yearly intervals, routine laboratory work-up, ultrasound abdomen and echocardiogram were all normal.

|

| Figure 3 |

Discussion

Based on the existing classification schemes [Table - 1], our case 1 can be characterized as phacomatosis cesiomarmorata (phacomatosis pigmentovascularis Vb) and cases 2, 3 and 4 as phacomatosis cesioflammea (phacomatosis pigmentovascularis IIb/IIa) [Table - 2]. The word 'caesius' used in Happle's classification is Latin for 'bluish-gray.'[5] Though the vascular lesions in all the three types in this classification (nevus flammeus, nevus roseus and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita)[5] are considered separate clinical entities and help to classify cases, histologically they are all capillary malformations.[9] Nevus roseus refers to a light red or pale pink birthmark contrasting with the dark hue of nevus flammeus whereas in cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita, the lesions tend to be reticulate. Considerable overlap of these lesions may be observed in several cases as among cases 1, 2 and 3 above [Table - 2].[10] Similarly, extracutaneous features may overlap among the different types of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis.[6],[7],[8],[10],[11],[12],[13] Conversely, a wide range of phenotypic variability, as evident in the three cases of phacomatosis cesioflammea described in this report [Table - 2], has been reported within each type of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis.[6],[7],[8],[10],[11],[12],[13]

Once the condition is suspected clinically, investigations including magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance angiography and venography of the brain, echocardiogram, detailed eye examination, skeletal survey and other relevant investigations to be done if the organ system is clinically suspected to be affected. They help to confirm the diagnosis and properly delineate the phenotypic characteristics in a given case. This further helps to differentiate this condition from other vascular syndromes including Sturge–Weber syndrome, Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome, blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome and Adam Oliver's syndrome.

Whether all the clinical variants of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis represent different entities at the molecular level is not yet settled. The sporadic nature and mosaic distribution of skin lesions suggest a postzygotic mutation. The concept of non-allelic twin spotting (didymosis), in which twin spots consisting of two genetically different clones of embryologically distinct neighboring cells are generated by somatic recombination on a background of normal cells, was proposed earlier to explain phacomatosis pigmentovascularis.[14] An interesting observation has been made recently in patients of phacomatosis pigmentokeratotica that was also earlier proposed to be an example of non-allelic twin spotting.[15] In phacomatosis pigmentokeratotica, authors have shown postzygotic activating HRAS [Harvey rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog] mutations in multipotent progenitor cells that were observed to give rise to both nevus sebaceous and melanocytic nevi, thus documenting it to be a mosaic RASopathy.[15] This observation negates the hypothesis of non-allelic twin spotting in this condition and it is now proposed that phacomatosis pigmentovascularis is a pseudodidymosis.[16] Since this could be true for other binary disorders as well, the concept of didymosis in these conditions has been considered untenable.[15],[16]

The gene/s responsible for phacomatosis pigmentovascularis is/are yet to be identified. Recently, somatic mutations of GNAQ [guanine nucleotide binding protein (G protein), q polypeptide] gene were identified in both port wine stains and Sturge–Weber syndrome indicating that there is a single underlying mechanism for Sturge–Weber syndrome and non-syndromic port wine stains.[17] Moreover, activating GNAQ mutations have also been identified in blue nevi, extensive nevi of Ota and uveal melanoma.[18] Sturge–Weber syndrome, blue nevi, nevi of Ota and uveal melanoma have all been reported in association with phacomatosis pigmentovascularis.[8],[19] Whether GNAQ mutations or mutations of other genes in pluripotent progenitor cells are responsible for various phacomatosis pigmentovascularis phenotypes needs to be determined.

Treatment and prognosis of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis depends upon the organ systems affected. For cutaneous lesions, a combined laser including Q-switched alexandrite laser for pigmented lesions and pulsed-dye laser for vascular lesions seem to be appropriate.[20],[21] Since most cases arise sporadically without any risk in subsequent pregnancies, prenatal screening is not necessary and this helps in reassuring patients/parents during genetic counseling.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Hasegawa Y, Yasuhara M. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type IVa. Arch Dermatol 1985;121:651-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Ota N, Kawamura T, Ito N. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis. Jpn J Dermatol 1947;57:1-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Torrelo A, Zambrano A, Happle R. Cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita and extensive mongolian spots: Type 5 phacomatosis pigmentovascularis. Br J Dermatol 2003;148:342-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Torrelo A, Zambrano A, Happle R. Large aberrant Mongolian spots coexisting with cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita (phacomatosis pigmentovascularis type V or phacomatosis cesiomarmorata). J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2006;20:308-10.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol 2005;141:385-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Cordisco MR, Campo A, Castro C, Bottegal F, Bocian M, Persico S, et al. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis: Report of 25 cases. Pediatr Dermatol 2001;18:70.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Vidaurri-de la Cruz H, Tamayo-Sánchez L, Durán-McKinster C, Orozco-Covarrubias Mde L, Ruiz-Maldonado R. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis II A and II B: Clinical findings in 24 patients. J Dermatol 2003;30:381-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Fernández-Guarino M, Boixeda P, de Las Heras E, Aboin S, García-Millán C, Olasolo PJ. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis: Clinical findings in 15 patients and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol 2008;58:88-93.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Happle R. Nevus roseus: A distinct vascular birthmark. Eur J Dermatol 2005;15:231-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Chang BP, Hsu CH, Chen HC, Hsieh JW. An infant with extensive Mongolian spot, naevus flammeus and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita: A unique case of phakomatosis pigmentovascularis. Br J Dermatol 2007;156:1068-71.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Okunola P, Ofovwe G, Abiodun M, Isah A, Ikubor J. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type IIb in association with external hydrocephalus. BMJ Case Rep 2012;2012. pii: Bcr1220115432.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Goyal T, Varshney A. Phacomatosis cesioflammea:First case report from India. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2010;76:307.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Garg A, Gupta LK, Khare AK, Kuldeep CM, Mittal A, Mehta S. Phacomatosis cesioflammea with Klippel Trenaunay syndrome: A rare association. Indian Dermatol Online J 2013;4:216-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Happle R, Steijlen PM. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis interpreted as a phenomenon of twin spots. Hautarzt 1989;40:721-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Groesser L, Herschberger E, Sagrera A, Shwayder T, Flux K, Ehmann L, et al. Phacomatosis pigmentokeratotica is caused by a postzygotic HRAS mutation in a multipotent progenitor cell. J Invest Dermatol 2013;133:1998-2003.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Happle R. Phacomatosis pigmentokeratotica is a “pseudodidymosis”. J Invest Dermatol 2013;133:1923-5.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Shirley MD, Tang H, Gallione CJ, Baugher JD, Frelin LP, Cohen B, et al. Sturge-Weber syndrome and port-wine stains caused by somatic mutation in GNAQ. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1971-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Van Raamsdonk CD, Bezrookove V, Green G, Bauer J, Gaugler L, O'Brien JM, et al. Frequent somatic mutations of GNAQ in uveal melanoma and blue naevi. Nature 2009;457:599-602.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Shields CL, Kligman BE, Suriano M, Viloria V, Iturralde JC, Shields MV, et al. Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis of cesioflammea type in 7 patients: Combination of ocular pigmentation (melanocytosis or melanosis) and nevus flammeus with risk for melanoma. Arch Ophthalmol 2011;129:746-50.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Kono T, Erçöçen AR, Chan HH, Kikuchi Y, Hori K, Uezono S, et al. Treatment of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis: A combined multiple laser approach. Dermatol Surg 2003;29:642-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Adachi K, Togashi S, Sasaki K, Sekido M. Laser therapy treatment of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis type II: Two case reports. J Med Case Rep 2013;7:55.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

9,299

PDF downloads

3,384