Translate this page into:

Role of molecular approaches to distinguish post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis from leprosy: A case study

Corresponding author: Prof. Mitali Chatterjee, Department of Pharmacology, Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and Research, 244 B, AJC Bose Road, Kolkata 700 020, West Bengal, India. ilatimc@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Roy S, Roy M, Nath S, Chaudhuri SJ, Ghosh MK, Mukherjee S, et al. Role of molecular approaches to distinguish post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis from leprosy: A case study. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2023;89:298-300.

Sir,

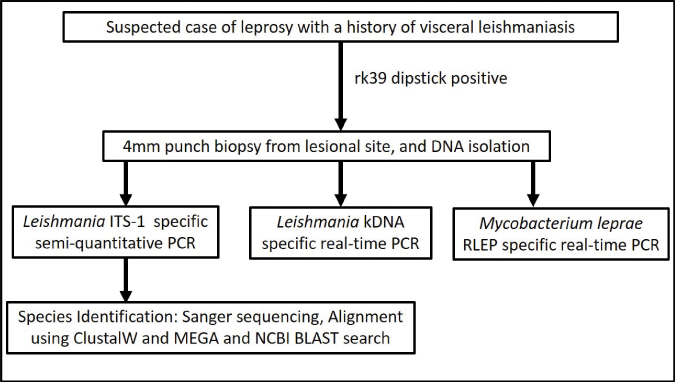

Visceral leishmaniasis, or kala-azar, is caused by the kinetoplastid parasite Leishmania donovani and its dermal sequel, post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis appears after apparent cure from visceral leishmaniasis. Post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis (PKDL) in South Asia occurs in approximately 10% of cases with a lag period following visceral leishmaniasis that ranges from 2 to 10 years.1 PKDL presents with either macular lesions or a combination of papules, nodules and macules, termed polymorphic. In visceral leishmaniasis endemic areas, cases of leprosy or Hansen’s disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae can present with similar macular or nodular lesions, along with nerve thickening and hypoesthesia, thus posing a diagnostic dilemma.2 As per the World Health Organization algorithm for diagnosis of post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis, the criteria include a history of visceral leishmaniasis, rK39 immunochromatographic strip test positivity, presence of amastigotes in slit skin smears, direct agglutination test and/or ELISA positivity (https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/78608/9789241505215_eng.pdf). In view of the clinical dilemma, molecular approaches like quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction and Sanger sequencing are employed to reach a conclusive diagnosis.

During an active field survey and medical camp conducted in Harirampur block, South Dinajpur district, West Bengal, a 36-year-old male presented with a macular hypoesthetic patch on the lower right side of back. The lesion was present for eight years along with ulnar nerve thickening [Figures 1a and b]. At presentation, the patient had no fever, hepatosplenomegaly or lymphadenopathy, but gave a history of visceral leishmaniasis 32 years ago for which he received sodium antimony gluconate.

- A 36-year old male with an isolated macular hypoesthetic patch on lower right back

- Magnified view of the macular lesion on lower right back

The rK39 dipstick was positive and DNA was isolated from a 4 mm skin biopsy. Primers for Leishmania specific Internal Transcribed Spacer-1 gene (LITSR 5’-CTGGATCATTTTCCGATG-3’, L5.8S 5’-TGATACCACTTATCGCACTT-3’)3 and kinetoplastid minicircle gene (kDNA F: 5’-CTTTTCTggTCCTCCgggTAgg-3’; kDNA R: 5’-CCACCCggCCCTATTTTACACCAA-3’) along with a 5’FAM tagged probe (5’-6FAMTTTTCgCAgAACgCCCCTACCCgC-BBQ were used to perform polymerase chain reaction and quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction, respectively.4 The Internal Transcribed Spacer-1 polymerase chain reaction 320 base pair (bp) product was visualised by 2% agarose gel electrophoresis, while the cycle threshold for the suspected case was 17.42. The Leishmania donovani WHO reference strain MHOM/IN/80/DD8 was a positive control and was positive by Internal Transcribed Spacer-1 polymerase chain reaction and quantitative polymerase chain reaction, cycle threshold being 20.19. The non-template control was undetermined. For quantification of parasite load, a standard curve was generated by serially diluting DNA isolated from 1 × 107 Leishmania donovani parasites and a quantitative polymerase chain reaction was performed.3

A Mycobacterium leprae-specific repetitive element (RLEP) based Taqman quantitative polymerase chain reaction was similarly undertaken using Mycobacterium leprae specific primers (RLEP-F: 5’-gCAgTATCgTgTTAgTgAA-3’; RLEP-R: 5’-CgCTAgAAggTTgCCgTATg-3’) and 5’FAM tagged probe (5’-6FAM-CgCCgACggCCggATCATCgABBQ) with a Mycobacterium leprae TN strain being the positive control.5 Cycle threshold value of the positive control was 27.99 and for the case, it was undetermined, confirming the patient was negative for leprosy [Figure 2].

- A proposed algorithm to distinguish post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis from leprosy. BLAST, Basic local alignment search tool; ITS-1, Internal transcribed spacer-1; kDNA, Kinetoplast DNA; MEGA, Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software; NCBI, National Center for Biotechnology Information; PCR, Polymerase chain reaction; RLEP, M. leprae-specific repetitive element

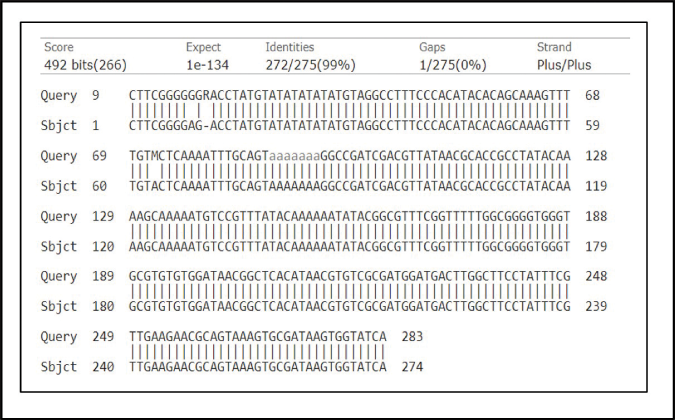

To confirm the Leishmania species, cycle sequencing and capillary electrophoresis was undertaken. Briefly, the chromatogram obtained was converted into a fast alignment file and analysed using Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis. Reference sequences of Internal Transcribed Spacer-1 of different species of Leishmania were retrieved from GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/GenBank/index.html) and aligned with the patient sequence via ClustalW and Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis software version 11.0 (Accession numbers KJ465104.1, KJ465105.1, MN244152.1 for Leishmania donovani, MH347947.1 for Leishmania tropica and KJ002553.1 for Leishmania. major). The patient’s sequence aligned with Leishmania donovani sequences. Furthermore, a BLAST search showed a 99.9% match with Leishmania donovani (Accession number KJ465105.1). (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PROGRAM=blastn&PAGETYPE=BlastSearch&LINKLOC=blasthome, Figure 3). The patient’s sequence was submitted to GenBank (Accession number ON817264).

- BLAST alignment of sequence sourced from the patient (Accession number ON817264) and Leishmania donovani sequence having accession number KJ465105.1 (98.9% match). BLAST, Basic local alignment search tool

Post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis cases form a relatively neglected component of the ongoing visceral leishmaniasis elimination programme, but being potent reservoirs for disease transmission, need urgent attention. The identification of macular post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis is challenging as their hypopigmented lesions mimic leprosy.6 As this patient presented with a single hypopigmented hypoesthetic patch and ulnar thickening, strongly suggestive of leprosy along with a prior history of visceral leishmaniasis, quantitative polymerase chain reaction for post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis and leprosy was necessary. The positivity of rK39, Internal Transcribed Spacer-1 polymerase chain reaction and quantitative polymerase chain reactionR confirmed Leishmania infection. Additionally, as the quantitative polymerase chain reaction of Mycobacterium leprae specific repetitive element was negative, it corroborated this was a case of post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis, masquerading as leprosy. As it was a single lesion, the causative species could have been Leishmania donovani, Leishmania major or Leishmania tropica. Therefore, it was necessary to define the causative species which was facilitated by Sanger sequencing, and confirmed the causative organism was Leishmania donovani.7

Due to the considerable overlap between macular post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis and leprosy, and the prolonged period of therapy necessary, multiple molecular approaches were applied for confirming the causative organism. Nerve inflammation and peripheral nerve involvement are symptoms suggestive of leprosy, but neural involvement has been reported in Sudanese post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis8 as also in a case from Bihar.9 Additionally, symptoms of leprosy can also overlap with psoriasis, pityriasis versicolor, granuloma annulare, syphilis, vitiligo and sarcoidosis.10 Taken together, suspected leprosy or post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis cases should ideally be tested for other diseases to ensure effective case management.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to the Department of Health and Family Welfare, West Bengal, for providing technical and personal support during the field surveys.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms.

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by the Indian Council of Medical Research, Govt. of India (Grant number: 6/9–7 [151] 2017– ECD II and 6/9–7(263)KA/2021/ECD–II);); Fund for Improvement of S&T infrastructure in Universities and Higher Educational Institutions (FIST) Program, Dept. of Science and Technology, Govt. of India (DST–FIST) (Grant number: SR/FST/LS1–663/2016); Dept. of Science and Technology, Govt. of West Bengal (Grant number: 969[Sanc.]ST/P/ S&T/9G–22/2016); Dept. of Science and Technology, Govt. of India and German Academic Exchange Service (DST–DAAD). MC is a recipient of a JC Bose Fellowship (JCB/2019/000043), Science Engineering & Research Board, DST, Govt. of India.

References

- Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis--an overview. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:921-31.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The clinical and immunological features of leprosy. Br Med Bull 200677-78, 103-21

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monitoring of parasite kinetics in Indian post-Kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66:404-10.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serological and molecular tools to diagnose visceral leishmaniasis: 2-years' experience of a single center in Northern Italy. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0183699.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enumeration of Mycobacterium leprae using real-time PCR. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e328.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- In-situ immune profile of polymorphic vs. macular Indian post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Int J Parasitol Drugs Drug Resist. 2019;11:166-76.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutaneous manifestations of human and murine leishmaniasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:1296.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Post-kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis in the Sudan: Peripheral neural involvement. Int J Dermatol. 1992;31:400-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nerve involvement in Indian post kala-azar dermal leishmaniasis. Acta Derm Venereol. 2004;84:245-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leprosy masquerading as tinea faciale. Ann Natl Acad Med Sci (India). 2022;58:50-1.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]