Translate this page into:

Tufted angioma with recurrent Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon

2 Department of Pathology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India

3 Department of Radiology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi, India

Correspondence Address:

Gomathy Sethuraman

Department of Dermatology and Venereology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi - 110 029

India

| How to cite this article: Bhari N, Jangid BL, Pahadiya P, Singh S, Arava S, Kumar A, Sharma VK, Sethuraman G. Tufted angioma with recurrent Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2018;84:121 |

Sir,

A 5-month-old male child presented with an erythematous plaque on the right cheek extending to the mandibular area and neck. The lesion was noticed at birth and had gradually increased in size with rapid growth over the past 2 months. There was no history of ulceration or bleeding. He did not have any associated systemic complaints. Examination revealed a dusky erythematous, firm and tender plaque of 10 cm × 14 cm size with surface nodularity on the right cheek and extending to the right side of the neck and chest [Figure - 1]a and [Figure - 1]b.

|

| Figure 1: |

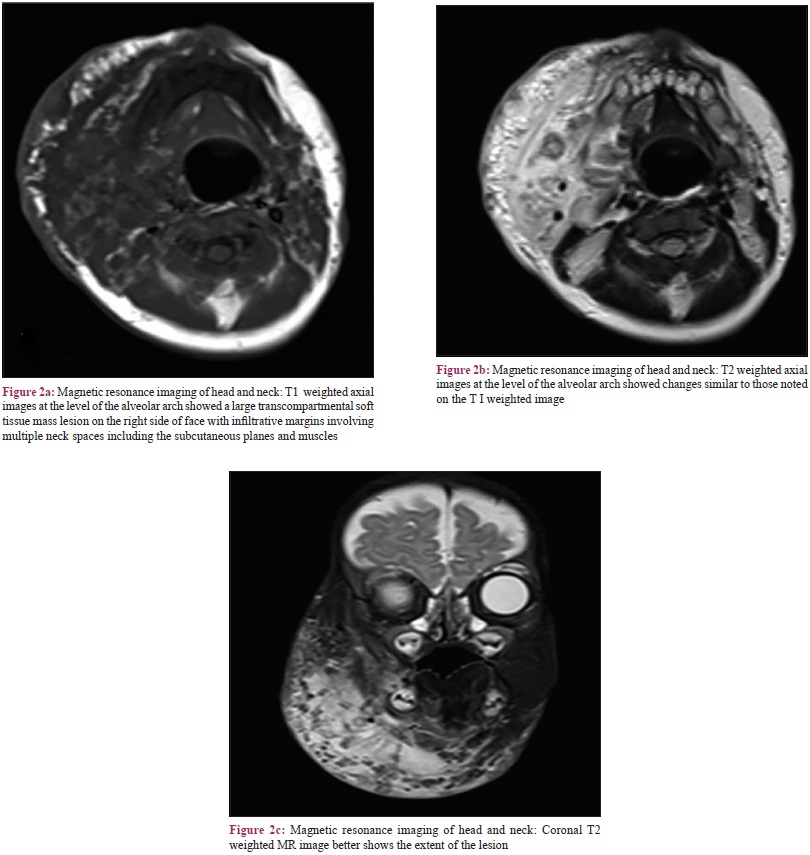

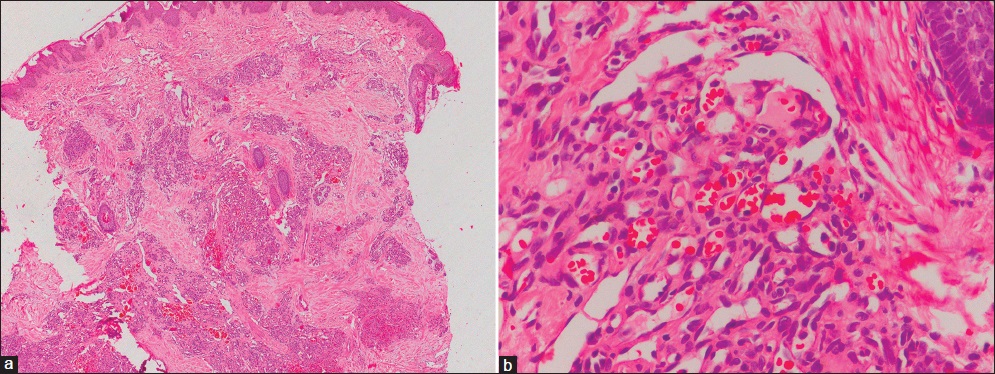

The child was admitted with a clinical diagnosis of vascular tumor, probably infantile hemangioma. Routine hematological investigations were within normal limits. Cutaneous ultrasonogram of the lesion showed extensive arterial vascularity, diffuse infiltration and an echogenic volume of 73.2 ccs suggestive of a proliferative hemangioma. Magnetic resonance imaging of the affected area revealed a large proliferative hemangioma on the right side of the face and upper neck involving the skin, subcutaneous tissue and muscles of the right infratemporal fossa, right premaxillary and premandibular region, chin and upper cervical region. The brain and airways were normal [Figure - 2]. Skin biopsy from the margin of the plaque showed nodular aggregates of proliferating endothelial cells, capillaries and lymphatics in the upper, mid- and lower dermis giving a 'cannon ball' appearance, suggestive of tufted angioma [Figure - 3]a and [Figure - 3]b. With these clinical findings and investigations, a final diagnosis of tufted angioma was made.

|

| Figure 2: |

|

| Figure 3: Skin biopsy shows (a) nodular aggregates in the upper, mid and lower dermis giving a cannon ball appearance (H and E, ×100). (b) These nodular aggregates are composed of proliferating endothelial cells, capillaries and lymphatics (H and E, ×400) |

During his hospital stay, the infant developed a sudden increase in the size of the plaque with extension up to the infraorbital region. Moreover, there was an increase in erythema and firmness of the plaque along with some difficulty in feeding [Figure - 1]c and [Figure - 1]d. A coagulation profile showed reduced platelets (23,000 cells/mcL) and fibrinogen (110 mg/dl), increased prothrombin time (15.1 s.) and D-dimer levels (>0.5 μg/ml). These findings along with the clinical features were suggestive of Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon. No episode of bleeding or ecchymosis was present. He was managed with weekly intravenous injections of vincristine (0.05 mg/kg) 0.35 mg/week, daily oral prednisolone (3 mg/kg/day) 20 mg, daily oral aspirin (10 mg/kg) 70 mg, one unit of fresh frozen plasma and platelet rich plasma. He recovered partially, however, he developed a similar episode within 3 days and hence daily oral propranolol was added at a dose of 2 mg/kg/day (14 mg). He continued to show similar fluctuation in clinical course in the next 14 days. Later, he was transferred to the pediatric intensive care unit. He showed partial clinical response and was discharged after 2 weeks on weekly injection vincristine and daily oral prednisolone, aspirin and propranolol. The child was lost to follow-up thereafter.

Tufted angioma is a rare vascular tumor that presents as a solitary, firm, dusky erythematous nodule. It shows an initial growth phase followed by a static course. Kasabach–Merritt syndrome/phenomenon, also known as “platelet trapping syndrome,” is an important complication of tufted angioma. It is characterized by the triad of consumptive coagulopathy, microangiopathic hemolytic anemia and rapidly enlarging vascular tumor with darkening of the lesion.[1],[2]

Kaposiform hemangioendothelioma and tufted angioma are the common primary causes of Kasabach–Merritt phenomenon. Infantile hemangiomas are not associated with this complication. In a retrospective review of 19 cases of Kasabach–Merritt syndrome, Kaposiform hemangioendotheliomas were seen in 18 (94.7%) cases and tufted angioma in 1 (5.3%).[3]

The treatment of choice is complete surgical excision or embolization by an interventional radiological procedure, limiting the tumor's blood supply.[4] As surgical options may not be feasible in all cases, systemic treatment may be required. Systemic corticosteroids (prednisolone 1–5 mg/kg/day) and vincristine (0.05 mg/kg/week intravenous) are the mainstay of medical therapy for Kasabach–Merritt syndrome.[4] Other useful drugs are interferon-α and antiplatelet drugs. Interferon-α is used at a dose of 0.5–10 million units/day or 3–4 times a week for 2–7 months. Ticlopidine (10 mg/kg/day) and aspirin (10 mg/kg/day) are the most commonly used antiplatelet drugs, although the risk of bleeding should be considered. Propranolol, sirolimus, human angiostatin and pegylated human megakaryocyte growth and development factors have also been tried. Coagulopathy and thrombocytopenia are managed by transfusion of platelets and cryoprecipitate/fresh frozen plasma.[4],[5]

The interesting feature in the present case was the multiple episodes of Kasabach–Merritt syndrome, which is quite rare. A combinational and multidisciplinary management approach is required due to the risk of serious, life-threatening complications such as shock and embolism.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

| 1. |

Ferrandiz-Pulido C, Mollet J, Sabado C, Ferrer B, Garcia-Patos V. Tufted angioma associated with Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon: A therapeutic challenge. Acta Derm Venereol 2010;90:535-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Sridhar S, Kuruvilla KA. Kasabach-Merritt syndrome. Indian Pediatr 2005;42:1045-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Yuan SM, Shen WM, Chen HN, Hong ZJ, Jiang HQ. Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon in Chinese children: Report of 19 cases and brief review of literature. Int J Clin Exp Med 2015;8:10006-10.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Tlougan BE, Lee MT, Drolet BA, Frieden IJ, Adams DM, Garzon MC. Medical management of tumors associated with Kasabach-Merritt phenomenon: An expert survey. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2013;35:618-22.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Hammill AM, Wentzel M, Gupta A, Nelson S, Lucky A, Elluru R, et al. Sirolimus for the treatment of complicated vascular anomalies in children. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2011;57:1018-24.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

3,436

PDF downloads

4,757