Translate this page into:

Biologic therapy in psoriasis

Correspondence Address:

Alka Dogra

Department of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology, Dayanand Medical College and Hospital, Ludhiana, Punjab - 141 001

India

| How to cite this article: Dogra A, Sachdeva S. Biologic therapy in psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol 2006;72:256-265 |

|

|

Introduction

Psoriasis is a common, chronic, disfiguring, inflammatory and proliferative condition of the skin, involving both genetic and environmental factors to play an important role. It is associated with significant morbidity, with 20-30% of the patients having severe disease.[1] Most of the traditional therapies available till now, aim at producing clinical improvement of the disease without targeting the factors that cause psoriasis. The recent advances in immunology based upon increased understanding of the basic pathophysiology of the disease and the advent of the genetic engineering techniques have shown the way to a new group of drugs referred to as biologicals, which aims at arresting the disease by targeting the basic pathogenic process.[2] The advantage of these biologic agents is their less toxic systemic side effects profiles, that improve the quality of life in psoriatic patients.[3]

Definition

The biologic therapy includes drugs which are proteins produced by living organisms to target specific points of inflammation cascade, including antibodies against cell surface markers, cytokines and adhesion molecules.[2] Currently available biologics for psoriasis, either target T-cells or antigen presenting cells (APC) or block the inflammatory action of TNF-a. The biologics represent an important addition to the psoriatic therapies and have a great impact on the disease course and quality of life of those afflicted with psoriasis.[4] They appear to offer a safe and effective alternative to conventional systemic therapies and phototherapy, for the treatment of moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis.[5]

Immunopathogenesis of psoriasis[6],[7],[8]

Psoriasis is an immunologically mediated disease caused by activation of T-lymphocytes that elaborate a Th1 type of immune response. The activation of T-cells is dependent upon its binding with the APCs. The T-cells get attached to the APCs through adhesion molecules, LFA-1 and CD2 on T-cells. The reciprocating cell adhesion molecules on APCs are ICAM-1 and LFA-3. After the T cell-APC binding has occurred through their respective surface adhesion molecules, the antigen is presented to the T-cells by the APCs. T-cells express the cell receptor (TCR) which recognizes the peptide antigen being presented by the APC, in the groove of the MHC complex. The antigen- stimulated activation leads to conversion of the naive T-cell into an antigen specific cell, which may develop into a memory cell that circulates in the body. After the activation of T-cells, a cascade of cytokines is secreted by different cells in the local microenvironment. The cytokines involved in the development of psoriasis include granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor (GMCSF), epithelial growth factor (EGF), IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, interferon-g and TNF-a. The effects of these cytokines include keratinocyte proliferation, neutrophil migration, potentiation of Th-1 type of responses, angiogenesis, up regulation of adhesion molecules and epidermal hyperplasia. Out of these cytokines, TNF-a plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. It leads to activation of both innate and acquired immune responses leading to chronic inflammation, tissue damage and keratinocyte proliferation. All these inflammatory responses and tissue changes lead to the clinical picture of psoriasis [Figure - 1].

Indication for biological therapy in psoriasis[1],[9]

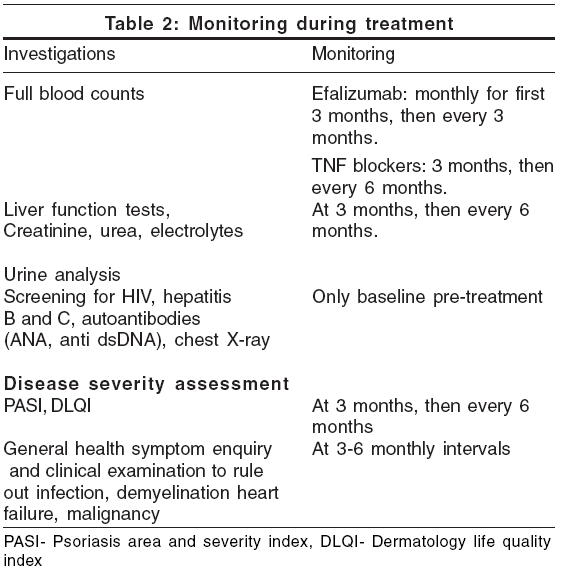

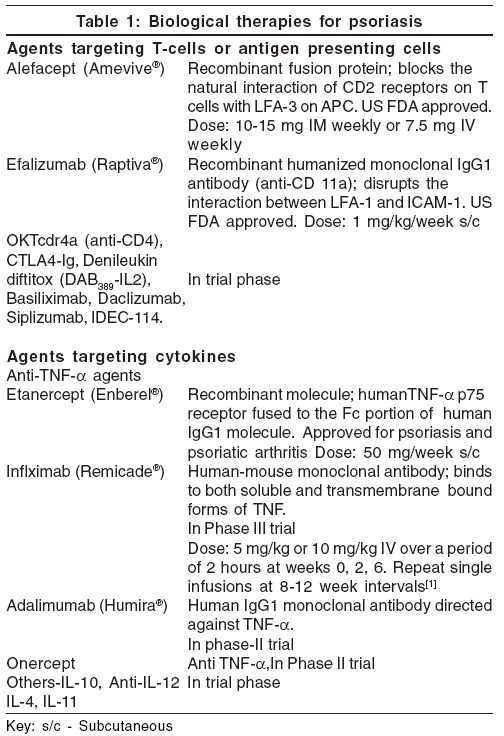

The biologic therapy should be kept reserved for severe psoriasis only. According to the guidelines provided by the British Association of Dermatologists, the patient must have severe disease defined as PASI score of 10 or more (or a BSA of 10% or greater where PASI is not applicable) and a DLQI (dermatology life quality index)> 10. The disease should be severe for 6 months and resistant to treatment and the patient should be a candidate for systemic therapy and should fall in one of the following clinical categories [Table - 1].

· Has developed or is at a higher risk than average risk of developing clinically important drug related toxicity and where alternative standard therapy (acitretin, cyclosporin, methotrexate, narrow band UVB and PUVA) cannot be used.

· Is intolerant, cannot receive or is unresponsive to standard therapy.

· Has disease that requires repeated inpatient management for control.

· Has significant co-existent unrelated morbidity which precludes the use of systemic agents like cyclosporin and methotrexate.

· Has severe, unstable, life threatening disease as pustular psoriasis or erythrodermic psoriasis.

· Has psoriatic arthritis.

Patient screening for biologic therapy[1],[9]

All patients should undergo a full clinical history, physical examination and further investigations as required, with particular reference to known toxicity profile of the agent being considered. The exclusion criteria include:

· Active tuberculosis. Patients with a history of inadequately treated tuberculosis should receive anti-tuberculosis therapy prior to anti-TNF treatment.

· Severe congestive heart failure (New York Heart Association grade III or IV). Patients with milder disease should be carefully assessed prior to treatment.

· Patients having> 200 treatments of PUVA are at a risk of developing malignancies with anti-TNF agents.

· History of demyelinating disease or optic neuritis.

· Hepatitis B and C positivity.

· HIV positivity.

· Premalignant states.

· Active infections. High risk includes chronic leg ulcers, persistent or recurrent chest infections and indwelling urinary catheter.

· Pregnancy and breast-feeding.

Pre-treatment investigations and monitoring

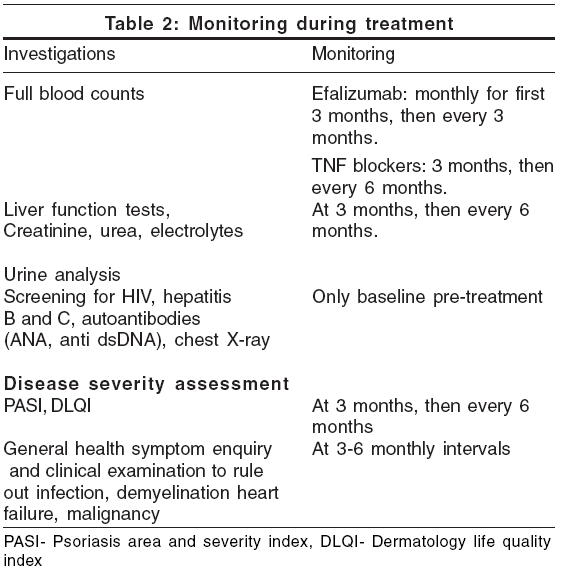

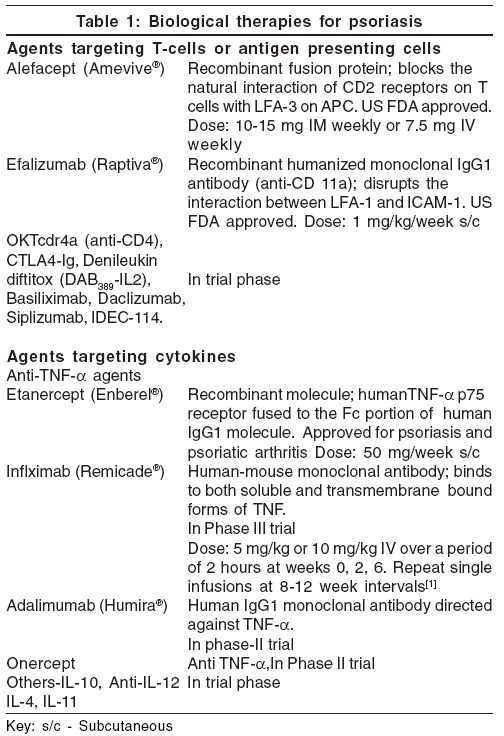

Complete blood count, liver and renal function tests, screening for hepatitis and HIV infection, anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-dsDNA, urine analysis and chest X-ray are recommended before the start of the treatment [Table - 2].[1] Tuberculin skin testing is required in patients undergoing treatment with anti-TNF agents. For efalizumab, haemogram (including platelet count) is recommended monthly for first 3 months and then every 3 months. For TNF blockers, it is done at 3 months initially and repeated every 6 months. Liver and renal function tests, serum electrolytes and urine analysis are done at 3 months initially and then every 6 months. Regular review of the clinical status of the patient including general health is essential to ensure early detection of adverse effects, particularly infection and malignancy.

Assessment of the response to biologicals

For evaluation of improvement in psoriasis, PASI (psoriasis area and severity index) and DLQI (dermatology life quality index) are recommended at 3 months initially and then every 6 months.[1] A favorable or adequate response to biologic treatment includes 50% or greater reduction in the baseline PASI score (or percentage BSA where the PASI is not applicable) and a 5-point or greater improvement in DLQI within 3 months of initiation of treatment. The PASI score is based on the severity of erythema, desquamation and plaque induration, as well as the extent of involvement in 4 separate body areas (head, trunk, upper extremities, lower extremities). PASI scores range from 0 to 72.

PASI 75 or a reduction in baseline PASI score of> 75%, is the standard used by FDA to assess the efficacy of a new psoriasis agent.[10] Estimation of body surface area affected by psoriasis may be done by using hand area, which represents approximately 1% of total body surface. The dermatology life quality index (DLQI) is a simple 10-question validated Quality of Life questionnaire. The DLQI scores range from 0 to 30. A DLQI of 10 or more correlates well with severe disease requiring admission, phototherapy or second line therapy and an improvement in DLQI of 5 or more points is considered a worthwhile criterion for response. Therapy should be withdrawn after 3 months if these criteria are not fulfilled .

Agents targeting T-cells or Antigen Presenting cells

Alefacept

Alefacept is a bivalent recombinant fusion protein composed of the first extracellular domain lymphocyte function antigen 3 (LFA-3), fused to the hinge CH2 domain and CH3 domain of human IgG1. The LFA-3 portion of alefacept binds to CD2 receptors on T-cells, thereby blocking their natural interaction with LFA-3 on APCs. The IgG1 portion of alefacept binds to FcγR receptor on natural killer cells to induce T-cell apoptosis. This cytotoxic effect is selective for the activated memory T-cells.[11]

The US food and drug administration (FDA) approved alefacept (Amevive ®, manufactured by Biogen Idec, Cambridge, MA and USA) in January 2003 for treatment in adult patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis, who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy. It is given by intramuscular or intravenous route with a dose of 10-15 mg IM weekly or 7.5 mg IV weekly and a 12 week course is recommended.[3],[11] Two 12-week courses of once-weekly intravenous alefacept 7.5 mg and placebo were given in a randomized double-blind study.[12] Patients were followed up for 12 weeks after each course. During treatment and follow-up of course 1, a 75% or greater reduction in the PASI was achieved by 28% of alefacept treated and 8% of placebo-treated patients ( p < 0.001). Patients who received a single course of alefacept and achieved a 75% or greater reduction from baseline PASI during or after treatment (without the use of phototherapy or systemic therapies), maintained a 50% or greater reduction in PASI for a median duration of more than 7 months. Among patients who received 2 courses of alefacept, 40 and 71% of patients achieved a 75% or greater and 50% or greater reduction in PASI, respectively, during the study period. Alefacept was well tolerated over both courses. In an international, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial with total of 507 patients with chronic plaque psoriasis, patients were administered either 10 mg of alefacept or 15 mg of alefacept once weekly for 12 weeks, followed by 12 weeks of observation. In the 15 mg group, 33% patients achieved 75% reduction in PASI, 2 weeks after the last dose and 71% maintained at least 50% improvement in PASI throughout the 12-week follow-up.[13] Comparatively, 28% patients achieved 75% reduction in PASI in the 10 mg group.

There were no opportunistic infections and no cases of rebound disease flare. Intramuscular therapy has been used in patients with extensive and recalcitrant palmoplantar psoriasis, with significant improvement.[14] Multiple courses of alefacept are effective in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis.[15] A single 12-week course of alefacept did not impair primary or secondary antibody responses to a neoantigen or memory responses to a recall antigen. The selective immunomodulatory effect of alefacept against a potentially pathogenic T-cell subset is associated with maintenance of a significant aspect of immune function (antibody response) to fight infection and response to vaccinations.[16] Alefacept reduces total lymphocyte count and CD4+ and CD8+cell counts. It is recommended that CD4 counts should be monitored weekly during therapy. Research is ongoing to examine the use of alefacept in psoriatic arthritis and its use in combination with other systemic psoriasis therapies and phototherapy.

Efalizumab

Efalizumab is a recombinant humanized monoclonal IgG1 antibody that binds to CD11a, the a subunit of leukocyte function-associated antigen 1 (LFA-1). It disrupts the interaction between LFA-1 and one of its ligands, intercellular adhesion molecules (ICAM-1), a cell surface molecule expressed by APCs. ICAM-1 is up-regulated on both endothelial cells and keratinocytes within psoriatic plaques.[17] Efalizumab destabilizes the binding of APCs and T-cells and thereby reduces the efficiency of initial T-cell activation in lymph nodes. It also decreases the trafficking of T-cells from the circulation into dermal and epidermal tissues and interferes with the secondary activation of memory-effector T-cells in the target tissues. The effects of efalizumab are confined only to those cells expressing LFA-1.

Efalizumab (Raptiva ®, manufactured by Genetech/Xoma, San Francisco CA, USA) was approved by the US FDA in October 2003 for the treatment of psoriasis.[3] It is currently the only biologic agent approved for continuous administration to adult patients.[17] The licensed dose of efalizumab is 1 mg/kg weekly as a subcutaneous, self administered injection for 12 weeks, following a first conditioning dose of 0.7 mg/kg, with the recommendation that treatment should be continued only in those who respond.[1],[17] No single dose should exceed 200 mg. A single use vial of efalizumab contains 125 mg of drug as sterile lyophilized powder, with preloaded single use syringes containing 1.3 ml of sterile water.[17] Patients should be instructed to rotate the injection sites between the thigh, abdomen, buttocks and upper arm with each dose.

The safety and efficacy of efalizumab has been evaluated in four large phase III studies in 2000 patients with moderate-to-severe chronic plaque psoriasis, most of whom had received previous systemic therapy for psoriasis.[18],[19],[20],[21] Efalizumab appears to be effective, with 27% of patients receiving a dose of 1 mg/kg weekly, achieving PASI 75 (>75% in reduction in baseline PASI score) compared to 4% in placebo group by week 12. Continuation of therapy beyond 12 weeks increases the response rate further. The relapse of psoriasis is usually evident about 2 months of discontinuation of therapy and rebound in approximately 5% of the patients, as defined by flaring>125% of baseline.

Acute flu- like symptoms including headache, chills, fever, nausea and myalgia may occur within 48 hours after administration of the first two doses. Discontinuation of therapy may be associated with an exacerbation of psoriasis, including the development of pustular or erythrodermic disease. Assessment of platelet count is recommended on start of therapy,and should be done periodically while the patient is on treatment. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia may occur 4-6 months after the start of treatment with efalizumab. The drug should be discontinued if thrombocytopenia or hemolytic anemia occurs. Concurrent immunosuppressive therapy should be avoided.[7]

Anti-tumour necrosis factor-α agents

Etanercept

Etanercept is a recombinant molecule comprising of the human TNF-a p75 receptor and the Fc portion of human IgG1 molecule fused together. It is a fully human dimeric fusion protein which functions as a TNF inhibitor by binding to and inactivating TNF-a, thereby preventing interaction with its cell surface receptors on target cells and blocking its pro-inflammatory effects.[1]

Etanercept (Enbrel ®, manufactured by Amgen Thousand Oaks, CA, USA and Wyeth Pharmaceuticals, Collegeville, PA, USA) is FDA approved for use as subcutaneous monotherapy in adults with moderate-to-severe psoriasis, who are candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy. The drug is also indicated for treatment of psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, polyarticular-course juvenile rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis.[22],[23] Etanercept is available in India now (Wyeth Ltd., Worli, Mumbai). It is available as 25 mg dose per vial as a sterile, white, preservative free lyophilized powder for parenteral administration, after reconstitution with 1 ml of the supplied sterile bacteriostatic water for injection. The adult dose is 50 mg/week, given subcutaneously for three months. It can be self-administered by the patient and the most common site for these injections are the abdomen, thighs and upper arms.[3] The most frequent side effects of etanercept include mild, transient injection site reactions, upper respiratory infections, headache and rhinitis.

The current license recommends intermittent courses no longer than 24 weeks.[1] Several small phase II studies[24],[25] and two key phase III[26],[27] randomized controlled trials involving about 1000 patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis (the majority of whom had received previous systemic treatment or PUVA), indicate that etanercept is an effective treatment for chronic plaque psoriasis. Efficacy is dose-related, with 34% of patients receiving 25 mg and 49% receiving 50 mg twice weekly, achieving PASI 75 after 12 weeks of treatment. Time to relapse, when defined as a 50% drop in the improvement in PASI achieved after 24 weeks of therapy, ranged from 70-91 days and appeared to be dose-related i.e. remission is maintained longer in higher dose group compared to the lower. Of patients achieving PASI 75 response at 24 weeks of therapy, 11% remained in remission for 1 year.

In a 24-week, double blind study,[26] efficacy of etanercept at different doses was compared with placebo. At week 12, there was an improvement from a base line of 75 percent or more in the PASI, in 4% of the patients in the placebo group, 14% in the low-dose etanercept group (25 mg once weekly), 34% in the medium-dose group (25 mg twice weekly) and 49 percent in the high-dose group (50 mg twice weekly) ( p < 0.001 for all three comparisons with the placebo group). The clinical responses continued to improve with longer treatment. At week 24, there was at least a 75% improvement in PASI in 25% of the patients in the low-dose group, 44% in the medium-dose group and 59% in the high-dose group. Etanercept was generally well tolerated.

Infliximab

Infliximab is a human-mouse monoclonal antibody[3] that binds to and inhibits the activity of TNF-a. It binds with high affinity to both soluble and transmembrane- bound forms of TNF-a and inhibits the ability of TNF-a to bind with its receptors. Because of inhibition of TNF-a activity, infliximab also indirectly inhibits production of other pro-inflammatory cytokines. It is also suggested that the binding of infliximab to membrane-bound TNF-a results in lysis of TNF-a producing cells by means of a complement or antibody dependent cell mediated cytotoxic mechanism.

Infliximab (trade name Remicade, manufactured by Centocor, Malveren, PA, USA) is approved for the treatment of Crohn′s disease and rheumatoid arthritis. It is effective in the treatment of moderate to severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis.[28] Infliximab may also be of value in recalcitrant or unstable disease and in generalized pustular psoriasis.[1] It is given as IV in doses of 5 or 10 mg/kg, over a period of 2 hours at weeks 0, 2, 6 and may be followed by repeat single infusions at 8-12 week intervals.[1],[28] A significant decrease in cytokines IL-6, VEGF, FGF and E-selectin has been detected at week 12 after infliximab infusions.[29]

In two randomized placebo-controlled trials,[30].[31] in patients with moderate to severe stable chronic plaque psoriasis, 75% improvement in PASI scores at week 10 has been noted in 87% of patients receiving standard induction course of therapy, with significant improvement in quality of life. Time to relapse following successful induction therapy is highly variable between individuals and may depend on the initial dose given: 73% of those given 10 mg/kg during induction maintained at least 50% improvement in PASI scores at week 26, compared to 40% of those given 5 mg/kg. Low dose infliximab has also been used in combination with methotrexate in severe recalcitrant psoriasis.[32] Unwanted adverse effects with infliximab include infection, infusion-related effects, headache, vertigo, flushing, gastrointestinal effects, abnormal hepatic functions and fatigue.[3]

Adalimumab

Adalimumab is a human IgG1 monoclonal antibody directed against TNF-a and blocks its interaction with the p55 and p75 cell surface receptors. It also lyses the cells that express surface TNF-a in the presence of complement.[3],[33] Adalimumab rapidly reverses the decrease in epidermal Langerhans cell density in psoriatic plaques and helps in the restoration of their density.[34] Currently, the drug is undergoing phase-II clinical trials for psoriasis and phase III studies for psoriatic arthritis.[35]

Adalimumab (Humira ®, manufactured by Abbott laboratories, Abbott park, IL, USA) is FDA approved for rheumatoid arthritis, in a dose of 40 mg s/c every other week as self-injection.[3],[33] In a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial,[36] patients with moderate to severe active psoriatic arthritis and a history of inadequate response to nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs were randomized to receive 40 mg adalimumab or placebo subcutaneously, every other week for 24 weeks. Study visits were at baseline, weeks 2 and 4 and every 4 weeks thereafter. Adalimumab was generally safe and well-tolerated, helped improving joint and skin manifestations significantly, inhibited structural changes on radiographs, lessened disability due to joint damage and brought improved quality of life in patients with moderate to severe active psoriatic arthritis.

Onercept

Onercept[37] is a recombinant human soluble p55 tumor necrosis factor binding protein under development (by Serono Inc. USA) for the potential treatment of a number of disorders, including Crohn′s disease, psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Currently, it is in phase II trial for treatment of psoriasis.

Other biological agents, targeting T-cells, antigen presenting cells and cytokines, presently in different phases of trial for treatment of psoriasis are: OKTcdr4a (anti-CD4), CTLA4-Ig, Denileukin diftitox (DAB 389 -IL2), Basiliximab, Daclizumab, Siplizumab, IDEC-114, IL-10, Anti IL-12, IL-4 and IL-11.[8],[9]

Denileukin diftitox (DAB 389 -IL2; Ontak) is a novel recombinant fusion protein approved by the US FDA for the treatment of relapsed or refractory cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. It consists of fragments of diphtheria toxin linked to human interleukin-2 and works by targeting the high-affinity interleukin-2 receptor. It was tried in patients with recalcitrant psoriasis in a double blind, phase II multicenter trial and the rate of improvement for treated patients was found to be significantly greater than those in placebo group.[38] Successful treatment for severe psoriasis and generalized pustular psoriasis has been reported with basiliximab, an interleukin-2 receptor (IL-2R; CD25) chimeric monoclonal antibody.[39],[40] Daclizumab, a humanized monoclonal anti-CD25 antibody has been tried in recalcitrant psoriasis[41] and in HIV-associated psoriatic erythroderma.[42]

Side effects of biologics[1],[3],[43],[44]

Allergic reaction and antibody formation

They are mostly seen with TNF-a blockers. Mild transient injection site reactions comprising of erythema, edema and bruising are noted with etanercept in 10-20% of cases. They resolve spontaneously in 2-3 days and tend to occur in the first month of therapy. Antibodies to etanercept may develop in 6% of patients. With infliximab, infusion reaction occurs during or within 1-2 hours of treatment and may affect up to 20% of all the patients treated. It may rarely result in anaphylactic shock. Acute flu-like symptoms including headache, chills, fever, nausea and myalgia may occur within 48 hours after administration of the first two doses of efalizumab.

Infections

Reactivation of tuberculosis may occur on treatment with anti-TNF-a agents, as TNF-a plays a key role in host defense against mycobacterial infection, particularly in granuloma formation and inhibition of mycobacterial dissemination. The risk of tuberculosis with infliximab has been estimated to be six times, in patients in trials for rheumatoid arthritis and Crohn′s disease, than that of untreated patients. Most patients were also receiving one or more immunosuppressive agents, which might have contributed to reactivation and dissemination of tuberculosis. However, no cases of tuberculosis have been reported in clinical trials of either infliximab or etanercept in psoriasis,[1] possibly due to minimal number of patients treated and probably, for monotherapy. Other serious infections reported with etanercept include sepsis secondary to Listeria monocytogenes and Histoplasma capsulatum. Severe disseminated opportunistic infections have been reported in the HIV positive patients.

Malignancy There is no increased rate of malignancy, including lymphoproliferative disorders, over the normal rates in the population. Patients who have been previously treated with PUVA may represent in particular, an at-risk group.

Neurological disease TNF blockers are associated with the development of or worsening of demyelinating disease. Worsening of multiple sclerosis and demyelination has been reported with infliximab.

Cardiovascular disease Worsening of congestive cardiac failure with TNF-α blockers is reported to occur. Patients with pre-existing heart failure (New York Heart Association class III and IV) failed to show benefit with TNF-α blockers and carried an excess mortality rate with high-dose infliximab.

Antinuclear antibodies and lupus like syndrome Antinuclear antibodies and anti-dsDNA antibodies may develop during therapy with anti-TNF-α agents, but it is not associated with symptoms and signs of lupus in the majority.

Hepatitis Rare cases of severe hepatitis have been reported following infliximab therapy, with onset of symptoms or signs occurring from 2 weeks to more than a year after initiation of treatment. The infliximab treatment should be stopped in the event of jaundice and/ or marked elevations (>5 times upper limit of normal) in liver enzymes.

Thrombocytopenia It can occur with efalizumab and warrants discontinuation of therapy.

Conclusion

Though biologic therapy seems to be an effective and promising treatment for moderate to severe chronic stable plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis, long-term studies need to be performed to assess the risk-benefit ratio of using these drugs over an extended period of time. Controlled trials have shown that the TNF-α inhibitors (etanercept, infliximab and adalimumab) and T-cell-targeted biologics (alefacept and efalizumab) significantly reduce symptoms and signs of psoriasis and improve function and quality of life. Injection site and intravenous reactions and increased risk of infection (in particular, reactivation of tuberculosis) are associated with the use of these agents. Increased risk of lymphoproliferative disease, the development of lupus-like syndromes and demyelination, including optic neuritis and reactivation of multiple sclerosis, are under evaluation in long-term follow-up studies. Though the cost of the biologics is a limiting factor, their unique action has definitely given a new hope for the management of psoriasis.

| 1. |

Smith CH, Anstey AV, Barker JN, Burden AD, Chalmers RJ, Chandler D, et al . British association of Dermatologists guidelines for use of biological interventions in psoriasis 2005. Br J Dermatol 2005;153:486-97.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 2. |

Mehlis S, Gordon KB. From laboratory to clinic: Rationale for biologic therapy. Dermatol Clin 2004;22:371-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 3. |

Kormeili T, Lowe NJ, Yamuchi PS. Psoriasis: Immunopathogenesis and evolving immunomodulators and systemic therapies; U.S experiences. Br J Dermatol 2004;151:3-15.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 4. |

Sauder DN, Mamelak AJ. Understanding the new clinical landscape for psoriasis: A comparative review of biologics. J Cutan Med Surg 2004;8:205-12.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 5. |

Rich SJ, Bello-Quintero CE. Advancements in the treatment of psoriasis: Role of biologic agents. J Manag Care Pharm 2004;10:318-25.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 6. |

Lowes MA, Lew W, Krueger JG. Current concepts in the immunopathogenesis of psoriasis. Dermatol Clin 2004;22:349-69.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 7. |

Joshi R. Immunopathogenesis of psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol 2004;70:10-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 8. |

Thappa DV, Laxmisha C. Immunomodulators in the treatment of psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol Venerol Leprol 2004;70:1-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 9. |

Sterry W, Barker J, Boehncke WH, Bos JD, Chimenti S, Christophers E, et al . Biological therapies in the systemic management of psoriasis: International Consensus Conference. Br J Dermatol 2004;151:3-17.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 10. |

Koo J, Khera P. Update on the mechanisms and efficacy of biological therapies for psoriasis. J Dermatol Sci 2005;38:75-87.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 11. |

Krueger GG. Current concepts and review of alefacept in the treatment of psoriasis. Dermatol Clin 2004;22:407-26.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 12. |

Krueger GG, Papp KA, Stough DB, Loven KH, Gulliver WP, Ellis CN. Alefacept Clinical Study Group. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study evaluating efficacy and tolerability of 2 courses of alefacept in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;47:821-33.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 13. |

Lebwohl M, Christophers E, Langley R, Ortonne JP, Roberts J, Griffiths CE, et al . Alefacept clinical study group. An international, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial of intramuscular alefacept in patients with chronic plaque psoriasis. Arch Dermatol 2003;139:719-27.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 14. |

Myers W, Christian L, Gottlieb AB. Treatment of palmoplantar psoriasis with intramuscular alefacept. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005;5:127-9.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 15. |

Menter A, Cather JC, Baker D, Farber HF, Lebwohi M, Darif M. The efficacy of multiple courses of alefacept in patients with moderate to severe chronic plaque psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;54:61-3.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 16. |

Gottlieb AB, Casale TB, Frankel E, Goffe B, Lowe N, Ochs HD, et al . CD4+ T-cell-directed antibody responses are maintained in patients with psoriasis receiving alefacept: Results of a randomized study. J Am Acad Dermatol 2003;49:816-25.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 17. |

Leonardi CL. Current concepts and review of efalizumab in the treatment of psoriasis. Dermatol Clin 2004;22:427-35.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 18. |

Lebwohl M, Tyring SK, Hamilton TK, Toth D, Glazer S, Tawfik NH, et al . A novel targeted T-cell modulator, efalizumab, for plaque psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2003;21:2004-13.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 19. |

Gordon KB, Papp KA, Hamilton TK, Walicke PA, Dummer W, Li N, et al . Efalizumab for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis: A randomized control trial. JAMA 2003;23:3073-80.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 20. |

Leonardi CL, Papp KA, Gordon KB, Menter A, Feldman SR, Caro I, et al . Extended efalizumab therapy improves chronic plaque psoriasis: Results from a randomized phase III trials. J Am Acad Dermatol 2005; 52:425-33.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 21. |

Menter A, Gordon K, Carey W, Hamilton T, Glazer S, Caro I, et al . Efficacy and safety observed during 24 weeks of efalizumab therapy in patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. Arch Dermatol 2005;141:31-8.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 22. |

Goldsmith DR, Wagstaff AJ. Etanercept: A review of its use in the management of plaque psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Am J Clin Dermatol 2005;6:121-36.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 23. |

Yamuchi PS, Gindi V, Lowe NJ. The treatment of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis with etanercept: Practical considerations on monotherapy, combination therapy and safety. Dermatol Clin 2004;22:449-59.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 24. |

Mease PJ, Goffe BS, Metz J, Vander SA, Finck B, Burge DJ. Etanercept in treatment of psoriatic arthritis and psoriasis: A randomized trial. Lancet 2000;356:385-90.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 25. |

Gottlieb AB, Matheson RT, Lowe N, Krueger GG, Kang S, Goffe BS, et al . A randomized trial of etanercept as monotherapy for psoriasis. Arch Dermatol 2003;139:1627-32.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 26. |

Leonardi CL, Powers JL, Matheson RT, Goffe BS, Zitnik R, Wang A, et al . Etanercept as monotherapy in patients with psoriasis. N Engl J Med 2003; 349: 2014-22.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 27. |

Papp KA, Tyring S, Lahfa M, Prinz J, Griffiths CE, Nakanishi AM, et al . A global Phase III randomized control trial of etanercept in psoriasis: Safety, efficacy and effect of dose reduction. Br J Dermatol 2005;152:1304-12.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 28. |

Winterfield L, Menter A. Psoriasis and its treatment with infliximab-mediated tumour necrosis factor a blockade. Dermatol Clin 2004; 22: 437-44.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 29. |

Mastroianni A, Minutilli E, Mussi A, Bordignon V. Cytokine profiles during infliximab monotherapy in psoriatic arthritis. Br J Dermatol 2005;153:531-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 30. |

Chaudhari U, Romano P, Mulcahy LD, Dooley LT, Baker DG, Gottlieb AB. Efficacy and safety of infliximab montherapy for plaque type psoriasis: A randomized trial. Lancet 2001;35:1842-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 31. |

Gottlieb AB, Evans R, Li S, Dooley LT, Guzzo CA, Baker D, et al . Infliximab induction therapy for patients with severe plaque type psoriasis: A randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 2004;51:534-42.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 32. |

Zargari O. Sustained effects of low dose infliximab in combination with methotrexate in the management of chronic recalcitrant psoriasis. Dermatol Online J 2005;11:21.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 33. |

Scheinfeld N. Adalimumab (HUMIRA): A review. J Drugs Dermatol 2003;2:375-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 34. |

Gordon KB, Bonish BK, Patel T, Leonardi CL, Nickloff BJ. The tumour necrosis factor-alpha inhibitor adalimumab rapidly reverses the decrease in epidermal Langerhans cell density in psoriatic plaques. Br J Dermatol 2005;153:945-53.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 35. |

Chew AL, Bennett A, Smith CH, Barker J, Kirkham B. Successful treatment of severe psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis with adalimumab. Br J Dermatol 2004;151:492-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 36. |

Mease PJ, Gladman DD, Ritchlin CT, Ruderman EM, Steinfeld SD, Choy EH, et al . Adalimumab for the treatment of patients with moderately to severely active psoriatic arthritis: Results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:3279-89.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 37. |

Nikas SN, Drosos AA. Onercept. Serono. Curr Opin Investig Drugs 2003;4:1369-76.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 38. |

Bagel J, Garland WT, Breneman D, Holick M, Littlejohn TW, Crosby D, et al . Administration of DAB389IL-2 to patients with recalcitrant psoriasis: A double blind, phase II multicenter trial. J Am Acad Dermatol 1998;3:938-44.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 39. |

Owen CM, Harrison PV. Successful treatment of severe psoriasis with basiliximab, an interleukin-2 receptor monoclonal antibody. Clin Exp Dermatol 2000;25:195-7.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 40. |

Salim A, Emerson RM, Dalziel KL. Successful treatment of severe generalized pustular psoriasis with basiliximab (interleukin-2 receptor blocker). Br J Dermatol 2000;143:1121-2.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 41. |

Wohlrab J, Fischer M, Taube KM, Marsch WC. Treatment of recalcitrant psoriasis with daclizumab. Br J Dermatol 2001;144: 209-10.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 42. |

Dichmann S, Mrowietz U, Schopf E, Norgauer J. Humanized monoclonal anti-CD25 antibody as a novel therapeutic option in HIV-associated psoriatic erythroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol 2002;47:635-6.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 43. |

Sukal SA, Nadiminti L, Granstein RD. Etanercept and demyelinating disease in a patient with psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol 2006;54:160-4.

[Google Scholar]

|

| 44. |

Scheinfeld N. Adalimumab: A review of side effects. Exp Opin Drug Saf 2005;4:637-41.

[Google Scholar]

|

Fulltext Views

11,704

PDF downloads

4,266